Order of the Star in the East

The Order of the Star in the East (OSE) was an organization established by the leadership of the Theosophical Society at Adyar, India from 1911 to 1927. Its mission was to prepare the world for the expected arrival of a messianic entity, the so-called World Teacher or Maitreya. The precursor of the OSE was the Order of the Rising Sun (1910–11) and the successor was the Order of the Star (1927–29). The precursor organization was formed after leading Theosophists discovered a likely "vehicle" for World Teacher Maitreya in the person of Jiddu Krishnamurti, an adolescent South Indian Brahmin. The founding of these organizations, as well as the disbanding of the OSE's successor in 1929 by Krishnamurti himself, led to crises in the Theosophical Society and to schisms in Theosophy.

Background

One of the central tenets of late 19th-century Theosophy as promoted by the Theosophical Society was the complex doctrine of The Intelligent Evolution of All Existence, occurring on a Cosmic scale, incorporating both the physical and non-physical aspects of the known and unknown Universe, and affecting all of its constituent parts regardless of apparent size or importance. The theory was originally promulgated in the Secret Doctrine, written in 1888 by Helena Blavatsky, one of the founders of contemporary Theosophy and of the Theosophical Society.[1]

According to this view, Humankind's evolution on Earth (and beyond) is part of the overall Cosmic evolution. It is reputedly overseen by a hidden Spiritual Hierarchy, the so-called Masters of the Ancient Wisdom, whose upper echelons consist of advanced spiritual beings. Blavatsky portrayed the Theosophical Society as being part of one of many attempts (or "impulses") by this hidden Hierarchy throughout the millennia to guide Humanity – in concert with the Intelligent Cosmic Evolutionary scheme – towards its ultimate, immutable evolutionary objective: the attainment of perfection and the conscious, willing participation in the evolutionary process. Blavatsky stated that these attempts require an Earth-based infrastructure (such as the Theosophical Society), to pave the way for the Hierarchy's physically appearing emissaries, "the torch-bearer[s] of Truth". The mission of these reputedly regularly appearing emissaries is to practically translate, in a way and language understood by contemporary humanity, the knowledge required to propel it to a higher evolutionary stage.[2]

History

Pre-history

Describing further the role of Theosophy and the Theosophical Society in the affairs of humankind, Blavatsky wrote about the possible future in her 1889 book The Key to Theosophy:

If the present attempt, in the form of our Society, succeeds better than its predecessors have done, then it will be in existence as an organized, living and healthy body when the time comes for the effort of the XXth century. The general condition of men's minds and hearts will have been improved and purified by the spread of its teachings, and, as I have said, their prejudices and dogmatic illusions will have been, to some extent at least, removed. Not only so, but besides a large and accessible literature ready to men's hands, the next impulse will find a numerous and united body of people ready to welcome the new torch-bearer of Truth. He will find the minds of men prepared for his message, a language ready for him in which to clothe the new truths he brings, an organization awaiting his arrival, which will remove the merely mechanical, material obstacles and difficulties from his path. Think how much one, to whom such an opportunity is given, could accomplish. Measure it by comparison with what the Theosophical Society actually has achieved in the last fourteen years, without any of these advantages and surrounded by hosts of hindrances which would not hamper the new leader.[3]

Following the original publication of the work, and based on this and other Blavatsky writings, Theosophists expected the future advent of the aforementioned "next impulse"; additional information about this was the purview of the Society's so-called Esoteric Section, which Blavatsky had founded and originally led.[4]

After Blavatsky’s death in 1891, influential Theosophist Charles Webster Leadbeater expanded on her writings about the Hierarchy and the Masters.[5] He formulated a Christology in which he identified Christ with the Theosophical representation of the Buddhist concept of Maitreya. Leadbeater believed that Maitreya-as-Christ had in several previous occasions manifested on Earth, in each case using a specially prepared person as a "vehicle". The incarnated Maitreya then assumed the role of World Teacher of Humankind, dispensing knowledge regarding underlying truths of Existence.[6]

Annie Besant, another well-known and influential Theosophist (and eventual close associate to Leadbeater), had also developed an interest on the advent of the next emissary from the Spiritual Hierarchy. In the decades of the 1890s and 1900s, along with Leadbeater and others, she became progressively convinced that this advent would happen sooner than Blavatsky's proposed timetable.[7] They came to believe it would involve the imminent reappearance of Maitreya as World Teacher – a monumental event in the Theosophical worldview. However not all Theosophical Society members accepted Leadbeater's and Besant's ideas on the matter; the dissidents charged them with straying from Theosophical orthodoxy and, along with other concepts developed by the two, Leadbeater's and Besant's writings on the Theosophical Maitreya were derisively labeled Neo-Theosophy by their opponents.[8]

Besant became President of the Theosophical Society in 1907, and added considerable weight to the belief of Maitreya's imminent manifestation; this eventually became a commonly held expectation among Theosophists.[9] Besant had started commenting on the possible imminent arrival of the next "emissary" as early as 1896; by 1909 the "coming Teacher" was a main topic of her lectures and writings.[10][11]

"Discovery" of Krishnamurti

Sometime in late April 1909, Leadbeater encountered fourteen-year-old Jiddu Krishnamurti on the private beach of the Theosophical Society Headquarters at Adyar.[12] At the time, Krishnamurti's father (who had been a longtime Theosophist) was employed by the Society, and the family lived next to the compound. Leadbeater, whose knowledge on occult matters was highly respected by the Society's leadership, came to believe young Krishnamurti was a suitable candidate for the "vehicle" of the World Teacher, and soon placed the boy under his and the Society's wing.[13] In late 1909, Annie Besant, by then President of the Society and head of its Esoteric Section, admitted Krishnamurti into both,[14] and in March 1910 she became his legal guardian.[15][16]

Following the "discovery", Leadbeater began occult investigations of Krishnamurti to whom he had assigned the pseudonym Alcyone – the name of a star in the Pleiades star cluster, and of characters from Greek mythology.[17] Leadbeater's belief about the boy's suitability as the "vehicle" was strengthened by clairvoyance-related revelations of Krishnamurti's reputed past and future lives. These were recorded and eventually published in Theosophical magazines starting April 1910 and in a book in 1913.[18] They were voraciously read and commented on in the Society, as according to Leadbeater, many Theosophists were contemporaneously involved in various "lives of Alcyone". Such involvement became a matter of status and prestige among Theosophists; it also contributed to factionalism within the Society.[19]

Order of the Rising Sun

In late 1910 the Order of the Rising Sun was founded by prominent Theosophist George Arundale (the official founding date was in January 1911). The organization was formed around a pre-existing study group of disciples headed by Krishnamurti, and was generally focused on the expected World Teacher; yet the newly "discovered" Krishnamurti was – somewhat obliquely – at the center of its attention.[20] In the meantime, the activities and proclamations of Leadbeater, Besant, and other senior Theosophists regarding Krishnamurti and the expected Teacher became entangled in prior disputes within and without the Theosophical Society, and also became subjects of new controversies.[21]

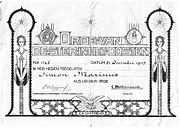

Order of the Star in the East

In April 1911 Besant founded the Order of the Star in the East (OSE), which replaced the Order of the Rising Sun. The High Offices of the organization were filled: "Mrs Besant and Leadbeater were made Protectors of the new Order of which Krishna [Jiddu Krishnamurti] was the Head, Arundale Private Secretary to the Head, and Wodehouse Organizing Secretary".[22] News regarding Krishnamurti, the Order, and its mission received widespread publicity and worldwide press coverage.[23]

In December 1911, during a ceremony officiated by Krishnamurti at the close of the annual Theosophical Convention (held that year at Benares), those present were reported to be suddenly overwhelmed by a strange feeling of "tremendous power", that seemed to be flowing through Krishnamurti. In Leadbeater's description, "it reminded one irresistibly of the rushing, mighty wind, and the outpouring of the Holy Ghost at Pentecost. The tension was enormous, and every one in the room was most powerfully affected." The next day, at a meeting of the Esoteric Section, Annie Besant for the first time announced that it was now obvious Krishnamurti was indeed the chosen "vehicle".[24]

In 1912, Krishnamurti's father sued Annie Besant in order to annul her guardianship of his son, which he had previously granted. Among other reasons stated in his deposition was his objection to the "deification" of Krishnamurti caused by Besant's "announcement that he was to be the Lord Christ, with the result that a number of respectable persons had prostrated before him." Besant eventually won the case on appeal.[25]

Also in 1912, the majority of the members of the German Section of the Theosophical Society followed its head, Rudolf Steiner, in splitting from the parent Society – partly due to disagreement over Besant's and Leadbeater's proclamations regarding Krishnamurti's messianic status.[26]

Controversy regarding the OSE and Krishnamurti spread to the Central Hindu College (CHC) in Varanasi, which had been founded by Annie Besant and counted several prominent Theosophists in its faculty and staff – including George Arundale, appointed its Principal in 1909. In 1913, a number of OSE supporters resigned their positions at the school, following opposition to the Order by the school's administration and Trustees, who considered its activities unacademical.[27][28]

The goal of the Order was to remove the mechanical, material obstacles and difficulties from the path of the World Teacher. By late 1913, the Order had about 15,000 members worldwide; most of them were also members of the Theosophical Society.[29] However membership was open to anyone, the only precondition being acceptance of the Order's Six Principles.

Six Principles

The Six Principles of the Order of the Star in the East were:[30]

- We believe that a great Teacher will soon appear in the world, and we wish so to live now that we may be worthy to know Him when He comes.

- We shall try, therefore, to keep Him in our minds always, and to do in His name, and therefore to the best of our ability, all the work which comes to us in our daily occupations.

- As far as our ordinary duties allow, we shall endeavour to devote a portion of our time each day to some definite work which may help to prepare for His coming.

- We shall seek to make Devotion, Steadfastness and Gentleness prominent characteristics of our daily life.

- We shall try to begin and end each day with a short period devoted to the asking of His blessing upon all that we try to do for Him and in His name.

- We regard it as our special duty to try to recognise and reverence greatness in whomsoever shown, and to strive to co-operate, as far as we can, with those whom we feel to be spiritually our superiors.

| Official Bulletins | |

|---|---|

| The Herald of the Star | |

| 1912–13, Adyar; 1914–27, London | |

| Jiddu Krishnamurti, editor | |

| OCLC 225662044 | |

| The Star Review | |

| 1928–29, London | |

| Emily Lutyens, editor | |

| OCLC 224323863 | |

| International Star Bulletin | |

| November 1927–July 1929, Ommen. | |

| D. Rajagopal & R. L. Christie, editors | |

| OCLC 34693176 | |

| [In addition several National Sections of the Order published their own Star bulletins] |

During the existence of the OSE, Krishnamurti held many discourses and lectures in several countries, and had a large following among the membership of the Theosophical Society. National Sections of the Order were organized in as many as forty countries. In 1921, the first International Star Congress was held in Paris, France, attended by 2,000 members out of then about 30,000 worldwide. At the Congress it was decided that there would be no special ceremonies or rituals associated with the Order or with the World Teacher.[31] Regularly scheduled multiday Star Camps, supported by well-organized facilities, were held for members in the Netherlands, the United States, and India, attended by thousands, with coverage provided by local and international media.[32][33]

In 1926 the OSE, which in affiliation with the Theosophical Society was by then producing a fair number of publications and propaganda material, organized its own publishing arm: the Star Publishing Trust, based in Eerde, Ommen, the Netherlands.[34] Along with an official international bulletin published in Ommen, national bulletins eventually appeared in twenty-one countries, and in fourteen different languages.[35] Also in 1926 it was reported that the Order's membership had reached about 43,000, two thirds of which were also members of the Theosophical Society.[36]

Claims and expectations

By year-end 1925, the efforts of prominent Theosophists – and their affiliated factions within the Society and the Order – to favorably position themselves for the expected Coming were reaching a climax. "Extraordinary" pronouncements of accelerated spiritual advancement were being made by various parties, privately disputed by others. Ranking members of the Order and the Society had publicly declared themselves to have been chosen as apostles of the new Messiah. The escalating claims of spiritual successes, and the internal (and hidden from the public) Theosophical politics, alienated an increasingly disillusioned Krishnamurti. He refused to recognize anyone as his disciple or apostle.[37] Additionally, World Teacher-related spinoff projects proliferated: in August 1925 the establishment of a "World Religion" and a "World University" were announced by the Theosophical leadership. Both of them were later "quietly shelved".[38]

At the opening of the annual Star Congress at Adyar on 28 December 1925, following the much anticipated but uneventful 1925 Theosophical Convention,[39] an event reminiscent of the one that happened in December 1911 occurred. Krishnamurti had been giving a speech about the World Teacher and the significance of his coming, when "a dramatic change" took place: his voice suddenly altered and he switched to first person, saying "I come for those who want sympathy, who want happiness, who are longing to be released, who are longing to find happiness in all things. I come to reform and not to tear down, I come not to destroy but to build." For many of the assembled who noticed, it was a "spine-tingling" revelation, "felt ... instantly and independently" – confirmation, in their view, that the manifestation of the Lord Maitreya through his chosen vehicle had begun.[40]

Order of the Star

The reputed manifestation of the World Teacher prompted a number of celebratory statements and assertions by prominent Theosophists that were not unanimously accepted by Society members. One result was the persistence of controversy regarding the project.[41] Besant and the rest of the International Leadership of the Society largely managed to contain the dissenters and the controversy, but in the process sustained unflattering publicity.[42] However the World Teacher Project was also receiving serious and neutral coverage in the global media, and according to reports it was followed sympathetically and with interest by non-Theosophists.[43]

In related developments following the perceived manifestation, Besant announced in January 1927, "The World Teacher is here",[44] and many members expected Krishnamurti's unequivocal public proclamation of his messianic status. Reflecting the new situation, in June 1927 the name of the organization was changed to Order of the Star, headquartered in Eerde, with close Krishnamurti associate and friend D. Rajagopal serving as the Chief Organizer. The renamed order had two objectives:[45]

- To draw together all those who believe in the Presence of the World Teacher in the world.

- To work with Him for the establishment of His ideas.

Complementing the reorganization and the proclamations of the World Teacher's manifestation, in 1928 the so-called World Mother Project, headed by Rukmini Devi Arundale (George Arundale's young wife), was put in motion by Theosophical leaders. Krishnamurti again distanced himself from this project, which the Indian and international press dubbed "Mrs. Besant's New Fad", and it was to be short-lived.[46]

Dissolution and repudiation

By the late 1920s, Krishnamurti's emphasis in public talks and private discussions had changed. He had been gradually discarding or contradicting Theosophical concepts and terminology, disagreeing with leading Theosophists, and talking less about the expected World Teacher.[47] This shift in emphasis mirrored fundamental changes in Krishnamurti as a person, including his increasing disenchantment with the World Teacher Project, which led to a complete reevaluation of his continuing association with it, the Theosophical Society, and Theosophy in general.[48] Finally, he disbanded the Order at Eerde, Ommen on 3 August 1929, in front of a radio audience, about 3,000 members, and Besant herself.[49][50] The Order had about 60,000 members at the time. In his speech dissolving the organization, Krishnamurti said:

I maintain that Truth is a pathless land, and you cannot approach it by any path whatsoever, by any religion, by any sect. That is my point of view, and I adhere to that absolutely and unconditionally. Truth, being limitless, unconditioned, unapproachable by any path whatsoever, cannot be organized; nor should any organization be formed to lead or to coerce people along any particular path.[51]

Despite the changes in Krishnamurti's outlook and pronouncements during the years leading to these events, the Dissolution of the Order and the ending of the World Teacher Project were unexpected by the great majority of their supporters and by Theosophists in general, and came as a complete shock. Following the Dissolution, prominent Theosophists openly or under various guises turned against Krishnamurti – including Leadbeater, who reputedly stated that "the Coming [of the World Teacher] had gone wrong".[52]

Soon after the Dissolution Krishnamurti severed his ties to Theosophy and the Theosophical Society.[53] He denounced the concept of saviors, leaders and spiritual teachers. Vowing to work towards setting humankind "absolutely, unconditionally free",[51] he repudiated any and all doctrines or theories of inner, spiritual and psychological evolution like those implied in the Theosophical tenets described above. He instead posited that his goal of complete psychological freedom can be realized only through the understanding of individuals' actual relationships with themselves, society, and nature.[54]

Krishnamurti returned to the donors the estates, property, and funds that had been given to the Order in its various incarnations,[55] and spent the rest of his life promoting his post-Theosophical message around the world as an independent speaker and writer. He became widely known as an original, influential thinker on philosophical, psychological, and religious subjects.

Consequences

In 1907 – the first year for which reliable records were kept[56] – the worldwide membership of the Theosophical Society was estimated at over 15,000. During the following two decades the membership suffered due to splits and resignations, but in the late 1920s it was steadily rising again; membership eventually peaked in 1928 at about 45,000.[57] The membership of the Order in its various guises was rising steadily through the years and was apparently still doing so at the time of its dissolution. Many members of the OSE were also members of the Theosophical Society;[58] consequently, as many as a third of the members of the Theosophical Society left "within a few years" of Krishnamurti's disbanding of the Order.[59] In the opinion of a Krishnamurti biographer, the Society, already in decline for other reasons, "was in disarray" upon the dissolution of the Order. While many Theosophical publications and leading members tried to minimize both the effect of Krishnamurti's actions and the defunct Order's importance, the "truth ... was that the Theosophical Society had been pole-axed. ... [Krishnamurti] had combatively challenged the central tenet of its beliefs".[60]

The failed project[61] lead to considerable analysis and retrospective evaluations by the Society and by well-known Theosophists, at that time[62] and since. It also resulted in governance changes in the Theosophical Society Adyar, a reorientation of its Esoteric Section, reexamination of parts of its doctrine, and reticence to outside questions regarding the OSE and the World Teacher Project.[63] In the opinion of one observer, Theosophical organizations, especially the Theosophical Society Adyar, by the close of the 20th century had yet to recover from Krishnamurti's rejection and the entire World Teacher affair, and entered the 21st still dealing with their effects.[64]

Notes

- ↑ See Intelligent evolution (in Theosophy); Blavatsky 1947, "The Three Postulates of the Secret Doctrine", "The pith and marrow of the Secret Doctrine". I: Cosmogenesis pp. 14–20 [in "Proem"], pp. 273–285 [in "Summing Up"]. Phoenix, Arizona: United Lodge of Theosophists [web publisher]. Retrieved on 2011-01-18.

- ↑ Blavatsky 1947, "Our Divine Instructors". II: Anthropogenesis pp. 365–378. Phoenix, Arizona: United Lodge of Theosophists [web publisher]. Retrieved on 2011-01-18.

- ↑ Emphasis in original. Blavatsky 1889, "The future of the Theosophical Society" pp. 304–307 (context at pp. 306–307). Wheaton, Maryland: theosophy.org [web publisher]. Retrieved on 2010-12-29.

- ↑ Blavatsky 1931; M. Lutyens 1975, pp. 10–11. Members of the Esoteric Section had access to occult instruction and a more detailed knowledge of the "inner order" and mission of the Society and its reputed hidden Masters or Mahātmās, members of the so-called Great White Brotherhood.

- ↑ Leadbeater 2007.

- ↑ Leadbeater 2007, pp. 31, 74, 191, 232, "Chapter XIII: The Trinity and the Triangles" pp. 250–260.

- ↑ Blavatsky 1889, p. 306. "But I must tell you that during the last quarter of every hundred years an attempt is made by those 'Masters,' of whom I have spoken, to help on the spiritual progress of Humanity in a marked and definite way. Towards the close of each century you will invariably find that an outpouring or upheaval of spirituality – or call it mysticism if you prefer – has taken place. Some one or more persons have appeared in the world as their agents, and a greater or less amount of occult knowledge and teaching has been given out."

- ↑ Thomas c. 1930s.

- ↑ Schuller 1999.

- ↑ M. Lutyens 1975, pp. 11–12, 46.

- ↑ AP 1909. Newswire report of Besant's early-20th-century lecture tour of the United States.

- ↑ M. Lutyens 1975, pp. 20–21.

- ↑ M. Lutyens 1975, pp. 12, 124–125. Krishnamurti was not the first, or only, candidate for "Vehicleship". Before him, Hubert van Hook, the young son of a high-ranking American Theosophist was considered promising by Leadbeater, while thirteen-year-old Indian Rajagopal Desikacharya (D. Rajagopal) was "discovered" in 1913, and for a time it was rumored in Theosophical circles that he might supplant Krishnamurti. However Krishnamurti was considered the most likely candidate for the "vehicle", and was extensively groomed for his future mission, for which the Society made available its resources. Rajagopal went on to become a decades-long close associate and friend of Krishnamurti, but their relationship soured in old age.

- ↑ M. Lutyens 1975, p. 30.

- ↑ M. Lutyens 1975, p. 40.

- ↑ Wood 1964. Eyewitness account of Krishnamurti's "discovery" and comments on related events and controversies. By one of Leadbeater's close associates. [Note weblink in reference is not at official Theosophical Society in America website. Link-specific content verified against original at New York Public Library Main Branch ("Search the Catalog", Classic Catalog (New York Public Library), retrieved 2010-12-19 : NYPL, "YBEA (American theosophist)" [call no.])].

- ↑ Besant & Leadbeater 2003, p. 9. "[To Krishnamurti] we have given a distinguishing name, so that he may be recognized under all the disguises put on to suit the part he is playing. These are mostly names of constellations, stars, or Greek heroes." Krishnamurti's pseudonym may be related to one of the mythical Pleiades or to another mythological Alcyone, a goddess whose story is related to the so-called halcyon days. In general, Theosophy assigns occult or esoteric significance to practically all ancient mythologies, whose theogonies are considered by Theosophical doctrine to be closely related to actual cosmological and astronomical events. The Pleiades star cluster specifically appears in many mythologies: Pleiades in folklore and literature.

- ↑ Besant & Leadbeater 1913.

- ↑ M. Lutyens 1975, pp. 23–24. Leadbeater proclaimed clairvoyance as a matter of fact; this was accepted by many Theosophists. Reincarnation is considered a fundamental doctrine in Theosophy. Besides Krishnamurti, Leadbeater assigned names with Esoteric Theosophical significance to several other actors in the "lives of Alcyone".

- ↑ M. Lutyens 1975, pp. 42–46. "George Arundale [appeared as] Fides in The Lives of Alcyone".

- ↑ Row 1911. Long letter by a senior Indian Theosophist published in Indian newspaper The Leader shortly after the formation of the Order of the Rising Sun. In it, Row disputes the Adyar-based leadership's claims about Krishnamurti and their positions on Theosophical doctrine.

- ↑ M. Lutyens 1975, pp. 46, 125, 227. A.E. Wodehouse, an educator and brother of the poet and writer P.G. Wodehouse, was another prominent Theosophist. He resigned his OSE position in late 1920 and was replaced by Krishnamurti's brother Nityananda ("Nitya"). After Nitya's death in 1925, D. Rajagopal assumed the post.

- ↑ Grand Forks Herald 1912. "A stripling of fifteen, Krishnamurti, a Hindu is thought by many Theosophists to be a second Messiah and a new sect has been formed for his support with the star of the east the emblem." [Note Krishnamurti was actually seventeen-years-old at the time of the article's publication. His age or birth date had been often misquoted by both the media and people close to him (M. Lutyens 1975, p. 308 [in "Notes and Sources": (note to) p. 2])].

- ↑ M. Lutyens 1975, pp. 54–55, "Chapter 4: First Initiation", "Chapter 5: First Teaching" pp. 29–46 [cumulative]. According to Leadbeater and other Theosophists, Krishnamurti had already previously passed a spiritual Initiation and had been accepted as a pupil by the Great White Brotherhood, the reputed hidden overseers of the Theosophical Society.

- ↑ M. Lutyens 1975, pp. 62, 82, 84, "Chapter 8: The Lawsuit" pp. 64–71.

- ↑ Steiner et al. 1993. Rudolf Steiner, at the time leader of the German Section of the Theosophical Society, rejected the claims made of Krishnamurti's messianic status. The resulting tensions between the German Section and Besant and Leadbeater was one of the reasons that led to a split in the Society and, in 1912, to Steiner forming the Anthroposophical Society; immediately following this step, Besant revoked the German Section's charter. The great majority of German members left the Theosophical Society in 1912–13 to join Steiner in the new group.

- ↑ M. Lutyens 1975, pp. 42–43, 61, 134. Besant and Leadbeater (who had been the subject of controversy and accusations in the past), portrayed much of the opposition to the OSE and to its mission – as well as the litigation regarding Krishnamurti's guardianship – as being part of wider, interrelated conflicts: the debates about the role of the Theosophical Society in Indian life, and the campaigns by political-religious opponents who disagreed with Besant's positions on Indian Home rule. Upon acceptance of the OSE members' resignation by the school authorities, Besant, then College President, tendered her own resignation. The school's Trustees asked her to reconsider, and she was later awarded an honorary doctorate; Das 1913. A contrary viewpoint to the Besant-Leadbeater portrayal. The author, a co-founder of the CHC, was opposed to the so-called World Teacher Project, the OSE, and eventually to Besant.

- ↑ Tillet 2007, "Chapter 15: Conflict over Krishnamurti" pp. 506–553. Information on the contemporary controversies regarding Krishnamurti, inside and outside the Theosophical Society.

- ↑ M. Lutyens 1975, p. 74. "Not all of them [i.e. OSE members] Theosophists".

- ↑ Wodehouse 1911. [Note weblink in reference is not at official Theosophical Society website. Link-specific content verified against original. New York Public Library Main Branch. NYPL, YAM p

.v [call no.]. Retrieved on 2011-06-16.. 408 - ↑ M. Lutyens 1975, p. 129. Some of those present attended at great financial cost, according to M. Lutyens.

- ↑ Landau 1943, pp. 88–103. Landau attended the 1927 Eerde gathering and Star Camp at Krishnamurti's invitation. He describes his impressions of the proceedings and of the attending members.

- ↑ Ross 2011, pp. 3–5. Star Camps were organized in Ojai, California beginning in 1927 on property that now predominantly belongs to the Krishnamurti Foundation of America.

- ↑ M. Lutyens 1975, p. 246.

- ↑ Star [b]. Bulletin of the United States Section of the Order.

- ↑ M. Lutyens 1975, p. 232n. From the 1926 Annual Report of the Order.

- ↑ M. Lutyens 1975, "Chapter 25: The Self Appointed Apostles", "Chapter 26: The First Manifestation" pp. 210–226 [cumulative].

- ↑ M. Lutyens 1975, pp. 214, 222.

- ↑ M. Lutyens 1975, p. 223. The 1925 Convention, taking place on the 50th anniversary of the founding of the Theosophical Society, had generated high expectations among Theosophists and Star members, with rumors of significant imminent "manifestations" related to the World Teacher. It had attracted large crowds and wide representation from the international media.

- ↑ M. Lutyens 1975, pp. 223–225. Mary Lutyens, then seventeen-years-old, was present at the event and was one of those affected – at the time she wrote of the perceived manifestation in her diary "as a fact", and still recalled the event as genuinely unusual and inexplicable in 1975; Vernon 2001, p. 158. Krishnamurti also thought the event important at the time of its happening, although he stated that he could not recall details. However not all of those present noticed anything unusual.

- ↑ New York Times 1926; Washington Post 1926 (report of the 1926 Convention of the UK Section of the Theosophical Society).

- ↑ Los Angeles Times 1926b. This press report considered "the strenuous efforts" of Besant "and her cult" regarding the World Teacher as objects of amusement. In contrast, Krishnamurti was said to "have retained no little common sense despite his recent dip into theosophy".

- ↑ Boston Daily Globe 1926. "Whether one believes in this 'second coming' or not, interest is being displayed in this question throughout the world. In many cases representatives of orthodox religious organizations have expressed receptiveness to this belief. ... There is widespread expectation of such an event, which disregards denominational and religious and even national boundaries. In India, where this movement began, this common expectation is revealed in an unusual way, when Mahometans, Buddhists and Christians sit together without any holy war starting, to hear Krishnamurti."

- ↑ M. Lutyens 1975, p. 241. Statement of Besant to the Associated Press.

- ↑ Star [a]; M. Lutyens 1975, pp. 245–246

- ↑ Tillet 2007, p. 766; M. Lutyens 1975, pp. 257, 258n. In the then-prominent Esoteric Christology of Theosophists, the World Mother corresponded to the Virgin Mary, the World Teacher being the embodiment of the Christ-principle. Rukmini Arundale was to be the World Mother's "vehicle"; Vernon 2001, pp. 174–175. However the project has also been described as an attempt (by leading Theosophists opposing him) to sideline Krishnamurti, who was by then becoming increasingly vocal in his "maverick" course.

- ↑ Los Angeles Times 1926a. Krishnamurti interviewed by the Los Angeles Times 25 May 1926, during a visit to Paris.

- ↑ Life-altering experiences (in Jiddu Krishnamurti); M. Lutyens 1975, "Chapter 18: The Turning Point"–"Chapter 21: Climax of the Process" pp. 152–188 [cumulative], pp. 219–222, 236, 265–266, 276. Krishnamurti experienced "life-changing" events of physical, psychological and spiritual nature starting in 1922. The events mystified the leadership of the Society who were ultimately unable to explain them, but provided for Krishnamurti an avenue of growth and life independent of Theosophy, the Order, and the Society. In addition, in November 1925, his younger brother Nityananda ("Nitya", 1898–1925) had died. His death deeply affected Krishnamurti, who had received assurances regarding Nitya's well-being by prominent Theosophists and reputedly, by members of the Society's hidden Spiritual Hierarchy. His continuing disagreements with leading Theosophists became more acute, despite Besant's efforts for conciliation. She offered to resign as President of the Society, and in 1928, in sympathy with Krishnamurti, closed the Esoteric Section. She reopened it after the dissolution of the Order.

- ↑ International Star Bulletin 1929. From the previously official bulletin of the Order of the Star. The bulletin published several issues post-dissolution, following Krishnamurti's new direction.

- ↑ Washington Post 1929; M. Lutyens 1975, p. 272. The so-called Dissolution Speech was broadcast by Dutch radio.

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 J. Krishnamurti 1929 [on cover: "January 11, 1911 Benares Ommen August 3, 1929"].

- ↑ M. Lutyens 1975, pp. 277–279, 315 [in "Notes and Sources": (notes to) pp. 278–279]. Letters by Krishnamurti to Emily Lutyens (December 1929) and Annie Besant (February 1930), and reaction of leading Theosophists to the Dissolution.

- ↑ M. Lutyens 1975, pp. 276, 285. However, he remained on friendly terms with individual members of the Society.

- ↑ J. Krishnamurti c. 1980.

- ↑ M. Lutyens 1975, p. 276.

- ↑ Tillet 2007, p. 943n[2].

- ↑ Taylor 1992, p. 328.

- ↑ Roe 1986, p. 288.

- ↑ Campbell 1980, p. 130.

- ↑ Vernon 2001, pp. 188–189.

- ↑ Schuller 1997. According to one theosophical commentator, the project may have been a failure relative only to contemporary expectations. In the cited paper he presents different viewpoints regarding its ultimate fate.

- ↑ Van der Leeuw 1930. "Thoughtful text" from a well-regarded Dutch Theosophist concerning the crisis in the Theosophical Society after Krishnamurti's Dissolution of the Order and rejection of his expected role.

- ↑ Vernon 2001, pp. 268–270. Vernon briefly comments on contemporary Theosophy. He writes of the changes in the Society's outlook since the "missionary" era of Annie Besant and Leadbeater, and of its continuing relationship with, and influence by, Krishnamurti and his message.

- ↑ Schuller 2008.

References

- Besant, Annie & Leadbeater, Charles W. (1913). Man: how, whence, and whither; a record of clairvoyant investigation. Adyar: Theosophical Publishing House. OCLC 871602.

- —— & Leadbeater, Charles W. (2003) [originally published 1924. Adyar: Theosophical Publishing House]. The lives of Alcyone (in 2 volumes). Part 1 (reprint of 1924 ed.). Whitefish, Montana: Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7661-4812-3. Google Books [web preview publisher]. Retrieved 2011-10-27.

- Blavatsky, Helena (1889). The key to Theosophy. London: The Theosophical Publishing Company. OCLC 315695318.

- Blavatsky, Helena (August 1931). "The Esoteric Section of the Theosophical Society: preliminary memorandum, 1888". The Theosophist (Adyar: Theosophical Publishing House) 52: 594–595. ISSN 0040-5892.

- Blavatsky, Helena (1947) [originally published 1888. London: The Theosophical Publishing Company]. The secret doctrine: the synthesis of science, religion, and philosophy (2 volumes) ("Facsimile" of 1st UK ed.). Los Angeles: The Theosophy Company. OCLC 224199940.

- Campbell, Bruce F. (1980). Ancient wisdom revived: a history of the Theosophical movement. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-03968-1.

- "Christ will soon visit Earth again. Head of Theosophical Society declares His spirit will manifest Itself". New York. Associated Press. 3 August 1909.

- "Cult is dissolved by Krishnamurti; surprises devotees by asserting organization is not necessary". The Washington Post. Associated Press (New York) [dateline Ommen, 3 August 1929]. 4 August 1929. p. M21. ISSN 0190-8286.

- Das, Bhagwan (Bhagavan) (1913). "The Central Hindu College and Mrs. Besant" (PDF). Parascience. Guerneville, California: The Science and Spirit Foundation. Retrieved 2010-04-12.

- "Editorial Policy". International Star Bulletin (Eerde, Ommen: Star Publishing Trust) 3 (2 [issues renumbered starting August 1929; volume not numbered in original]): 4. September 1929. OCLC 34693176.

- Jiddu, Krishnamurti (1929). The dissolution of the Order of the Star: a statement (pamphlet). Eerde, Ommen: Star Publishing Trust. OCLC 32954280. J. Krishnamurti Online [web publisher]. Retrieved 2011-11-02.

- Jiddu, Krishnamurti (c. 1980). "The Core of the Teachings". J. Krishnamurti Online. Krishnamurti Foundations. Retrieved 2011-01-28.

- Landau, Rom (1943) [originally published 1935. London: I. Nicholson and Watson]. God is my adventure – a book on modern mystics, masters, and teachers. London: Faber and Faber. OCLC 561790498. Archived 2005-04-28 by Osmania University (Hyderabad, India). Retrieved 2010-09-25.

- Leadbeater, Charles W. (2007) [originally published 1925. Adyar: Theosophical Publishing House]. The masters and the path (reprint ed.). New York: Cosimo Classics. ISBN 978-1-60206-333-4.

- Lutyens, Mary (1975). Krishnamurti: the years of awakening (1st US ed.). New York: Farrar Straus and Giroux. pp. 10–11. ISBN 978-0-374-18222-9.

- "Messiah pooh-poohs role; Krishnamurti declares world saving mere rubbish; plans to study on Los Angeles ranch. (By cable – exclusive dispatch)". The Los Angeles Times. 26 May 1926. p. 6. ISSN 0458-3035.

- "New religion is headed by youth". Grand Forks Herald (Grand Forks, North Dakota). 2 April 1912. p. 1. OCLC 12165939.

- Roe, Jill (1986). Beyond belief: Theosophy in Australia 1879-1939. Sydney: University of New South Wales Press. ISBN 978-0-86840-042-6.

- Ross, Joseph E. (2011). Krotona, Theosophy and Krishnamurti, 1927-1931. Ojai, California: Krotona Archives. ISBN 978-0-925943-15-6. Retrieved 2011-11-02.

- Row, M. C. Nanjunda (28 January 1911). "Thoughts about matters Theosophical (Letters to the Editor)". The Leader (Allahabad: K. Ram). pp. 20–21. OCLC 29040706.

- Schuller, Govert W. (1997). "Krishnamurti and the World-Teacher Project: Some Theosophical Perceptions". Theosophical History. Occasional Papers (Fullerton, California: Theosophical History Foundation) 5. ISSN 1068-2597. Carol Stream, Illinois: alpheus.org [web publisher]. Retrieved 2010-05-17.

- Schuller, Govert W. (1999). "The Masters and their emissaries: From H.P.B. to Guru Ma and beyond". Alpheus. Carol Stream, Illinois: Govert W. Schuller. (2nd ed.). Retrieved 2010-10-22.

- Schuller, Govert W. (2008). "The State of the TS (Adyar) in 2008: a psycho-esoteric interpretation" (DRAFT). Alpheus. Carol Stream, Illinois: Govert W. Schuller. Retrieved 2010-10-13.

- Steiner, Rudolph; Buursink, Marijke; Schuwirth, Wim; Blomaard, Pim & Mees, Wijnand (1993). Wegen naar Christus [Roads to Christ]. Werken en voordrachten (in Dutch) 2. Partially translated from German by Marijke Buursink. Zeist, Netherlands: Vrij Geestesleven. ISBN 978-90-6038-512-8.

- Taylor, Anne (1992). Annie Besant: a biography. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-211796-0.

- "The Order of the Star". The Star (Los Angeles: Star Publishing Trust) (All issues): back matter. All dates. OCLC 10990552. Check date values in:

|date=(help)

- "The Star: its purpose and policy". The Star (Los Angeles: Star Publishing Trust) (All issues): back matter. All dates. OCLC 10990552. Check date values in:

|date=(help)

- "Theosophist 'Messiah' will visit America; mrs. Besant to accompany Hindu on world tour – dissenters are quitting cult. (By wireless to The New York Times)". The New York Times. 2 March 1926. p. 8. ISSN 0362-4331.

- "Theosophists give Mrs. Annie Besant confidence ballot; veteran leader threatens to resign as Head of British movement. Delegates divided on 'World Teacher'; official points out that vote is no indorsement of Krishnamurti". The Washington Post. Associated Press (New York) [dateline London, 12 June 1926]. 13 June 1926. p. M13. ISSN 0190-8286.

- "Theosophists prepare for their new Messiah". Boston Daily Globe (Globe Publishing). 20 March 1926. p. A4. OCLC 12674818.

- Thomas, Margaret A (c. 1930s) [originally compiled by Thomas c. 1920s]. "Section I: Differences in Teaching" (PDF). Theosophy or Neo-Theosophy? (PDF). London: Margaret A. Thomas. pp. 1–34. OCLC 503841852. Tucson, Arizona: Blavatsky Study Center [web publisher]. Retrieved 2011-05-15.

- Tillet, Gregory J. (2007) [originally submitted 1985, awarded 1986 by the Dept. of Religious Studies, University of Sydney]. Charles Webster Leadbeater 1854–1934: a biographical study (Ph.D thesis). Sydney: Sydney escholarship. OCLC 271774444. hdl:2123/1623.

- Van der Leeuw, Johannes J. (1930). Revelation or realization: the conflict in Theosophy (pamphlet). Amsterdam: Theosofische Vereeniging Uitgevers Maatschappy. OCLC 500301988. Carol Stream, Illinois: alpheus.org [web publisher]. Retrieved 2010-10-03.

- Vernon, Roland (2001). Star in the east: Krishnamurti: the invention of a messiah. New York: Palgrave. ISBN 978-0-312-23825-4.

- Wodehouse, Ernest A. (1911). The Order of the Star in the East: its outer and inner work (pamphlet). Adyar: Theosophist Office. OCLC 258767581. Groningen, Netherlands: katinkahesselink.net [web publisher]. Retrieved 2010-10-08.

- Wood, Ernest (December 1964). "No Religion Higher than Truth". The American Theosophist (Wheaton, Illinois: Theosophical Society in America) 52 (12): 287–290. ISSN 0003-1402. Groningen, Netherlands: katinkahesselink.net [web publisher]. Retrieved 2010-08-14.

External links

- "Jiddu Krishnamurti Quotes and Stories" – From katinkahesselink.net, an independent website by a member of Theosophical Society Adyar. Scroll to section "Material from before the disolvement [sic] of the order of the star". Katinka Hesselink. Retrieved on 2010-10-03.

- "Krishnamurti" – Extensive information on the relationship between Krishnamurti and the Theosophical Society from Alpheus, an independent website. "Alpheus is a Web site dedicated to esoteric and other alternative interpretations of history." Govert W. Schuller. Retrieved on 2010-10-03.