Order of magnitude

Orders of magnitude are written in powers of 10. For example, the order of magnitude of 1500 is 3, since 1500 may be written as 1.5 × 103.

Differences in order of magnitude can be measured on the logarithmic scale in "decades" (i.e., factors of ten).[1] Examples of numbers of different magnitudes can be found at Orders of magnitude (numbers).

We say two numbers have the same order of magnitude of a number if the big one divided by the little one is less than 10. For example, 23 and 82 have the same order of magnitude, but 23 and 820 do not."[2] — John C. Baez

Uses

Orders of magnitude are used to make approximate comparisons. If numbers differ by 1 order of magnitude, x is about ten times different in quantity than y. If values differ by 2 orders of magnitude, they differ by a factor of about 100. Two numbers of the same order of magnitude have roughly the same scale: the larger value is less than ten times the smaller value.

| In words (long scale) |

In words (short scale) |

Prefix | Symbol | Decimal | Power of ten |

Order of magnitude |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| quadrillionth | septillionth | yocto- | y | 0.000,000,000,000,000,000,000,001 | 10−24 | −24 |

| trilliardth | sextillionth | zepto- | z | 0.000,000,000,000,000,000,001 | 10−21 | −21 |

| trillionth | quintillionth | atto- | a | 0.000,000,000,000,000,001 | 10−18 | −18 |

| billiardth | quadrillionth | femto- | f | 0.000,000,000,000,001 | 10−15 | −15 |

| billionth | trillionth | pico- | p | 0.000,000,000,001 | 10−12 | −12 |

| milliardth | billionth | nano- | n | 0.000,000,001 | 10−9 | −9 |

| millionth | millionth | micro- | µ | 0.000,001 | 10−6 | −6 |

| thousandth | thousandth | milli- | m | 0.001 | 10−3 | −3 |

| hundredth | hundredth | centi- | c | 0.01 | 10−2 | −2 |

| tenth | tenth | deci- | d | 0.1 | 10−1 | −1 |

| one | one | – | – | 1 | 100 | 0 |

| ten | ten | deca- | da | 10 | 101 | 1 |

| hundred | hundred | hecto- | h | 100 | 102 | 2 |

| thousand | thousand | kilo- | k | 1,000 | 103 | 3 |

| million | million | mega- | M | 1,000,000 | 106 | 6 |

| milliard | billion | giga- | G | 1,000,000,000 | 109 | 9 |

| billion | trillion | tera- | T | 1,000,000,000,000 | 1012 | 12 |

| billiard | quadrillion | peta- | P | 1,000,000,000,000,000 | 1015 | 15 |

| trillion | quintillion | exa- | E | 1,000,000,000,000,000,000 | 1018 | 18 |

| trilliard | sextillion | zetta- | Z | 1,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 | 1021 | 21 |

| quadrillion | septillion | yotta- | Y | 1,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 | 1024 | 24 |

The order of magnitude of a number is, intuitively speaking, the number of powers of 10 contained in the number. More precisely, the order of magnitude of a number can be defined in terms of the common logarithm, usually as the integer part of the logarithm, obtained by truncation. For example, the number 4,000,000 has a logarithm (in base 10) of 6.602; its order of magnitude is 6. When truncating, a number of this order of magnitude is between 106 and 107. In a similar example, with the phrase "He had a seven-figure income", the order of magnitude is the number of figures minus one, so it is very easily determined without a calculator to be 6. An order of magnitude is an approximate position on a logarithmic scale.

An order-of-magnitude estimate of a variable whose precise value is unknown is an estimate rounded to the nearest power of ten. For example, an order-of-magnitude estimate for a variable between about 3 billion and 30 billion (such as the human population of the Earth) is 10 billion. To round a number to its nearest order of magnitude, one rounds its logarithm to the nearest integer. Thus 4,000,000, which has a logarithm (in base 10) of 6.602, has 7 as its nearest order of magnitude, because "nearest" implies rounding rather than truncation. For a number written in scientific notation, this logarithmic rounding scale requires rounding up to the next power of ten when the multiplier is greater than the square root of ten (about 3.162). For example, the nearest order of magnitude for 1.7 × 108 is 8, whereas the nearest order of magnitude for 3.7 × 108 is 9. An order-of-magnitude estimate is sometimes also called a zeroth order approximation.

An order-of-magnitude difference between two values is a factor of 10. For example, the mass of the planet Saturn is 95 times that of Earth, so Saturn is two orders of magnitude more massive than Earth. Order-of-magnitude differences are called decades when measured on a logarithmic scale.

Non-decimal orders of magnitude

Other orders of magnitude may be calculated using bases other than 10. The ancient Greeks ranked the nighttime brightness of celestial bodies by 6 levels in which each level was the fifth root of one hundred (about 2.512) as bright as the nearest weaker level of brightness, and thus the brightest level being 5 orders of magnitude brighter than the weakest indicates that it is (1001/5)5 or a factor of 100 times brighter.

The different decimal numeral systems of the world use a larger base to better envision the size of the number, and have created names for the powers of this larger base. The table shows what number the order of magnitude aim at for base 10 and for base 1,000,000. It can be seen that the order of magnitude is included in the number name in this example, because bi- means 2 and tri- means 3 (these make sense in the long scale only), and the suffix -illion tells that the base is 1,000,000. But the number names billion, trillion themselves (here with other meaning than in the first chapter) are not names of the orders of magnitudes, they are names of "magnitudes", that is the numbers 1,000,000,000,000 etc.

| order of magnitude | is log10 of | is log1000000 of | short scale | long scale |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 10 | 1,000,000 | million | million |

| 2 | 100 | 1,000,000,000,000 | trillion | billion |

| 3 | 1000 | 1,000,000,000,000,000,000 | quintillion | trillion |

SI units in the table at right are used together with SI prefixes, which were devised with mainly base 1000 magnitudes in mind. The IEC standard prefixes with base 1024 were invented for use in electronic technology.

The ancient apparent magnitudes for the brightness of stars uses the base ![\sqrt[5]{100} \approx 2.512](../I/m/725de7c81fbb2af1095267fdb31e9345.png) and is reversed. The modernized version has however turned into a logarithmic scale with non-integer values.

and is reversed. The modernized version has however turned into a logarithmic scale with non-integer values.

Extremely large numbers

For extremely large numbers, a generalized order of magnitude can be based on their double logarithm or super-logarithm. Rounding these downward to an integer gives categories between very "round numbers", rounding them to the nearest integer and applying the inverse function gives the "nearest" round number.

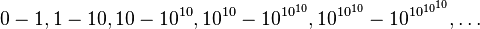

The double logarithm yields the categories:

- ..., 1.0023–1.023, 1.023–1.26, 1.26–10, 10–1010, 1010–10100, 10100–101000, ...

(the first two mentioned, and the extension to the left, may not be very useful, they merely demonstrate how the sequence mathematically continues to the left).

The super-logarithm yields the categories:

-

, or

, or

- negative numbers, 0–1, 1–10, 10–1e10, 1e10–101e10, 101e10–410, 410–510, etc. (see tetration)

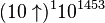

The "midpoints" which determine which round number is nearer are in the first case:

- 1.076, 2.071, 1453, 4.20e31, 1.69e316,...

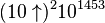

and, depending on the interpolation method, in the second case

- −.301, .5, 3.162, 1453, 1e1453,

,

,  ,... (see notation of extremely large numbers)

,... (see notation of extremely large numbers)

For extremely small numbers (in the sense of close to zero) neither method is suitable directly, but the generalized order of magnitude of the reciprocal can be considered.

Similar to the logarithmic scale one can have a double logarithmic scale (example provided here) and super-logarithmic scale. The intervals above all have the same length on them, with the "midpoints" actually midway. More generally, a point midway between two points corresponds to the generalised f-mean with f(x) the corresponding function log log x or slog x. In the case of log log x, this mean of two numbers (e.g. 2 and 16 giving 4) does not depend on the base of the logarithm, just like in the case of log x (geometric mean, 2 and 8 giving 4), but unlike in the case of log log log x (4 and 65536 giving 16 if the base is 2, but, otherwise).

See also

- Big O notation

- Decibel

- Names of large numbers

- Names of small numbers

- Number sense

- Orders of approximation

- Orders of magnitude (numbers)

References

- ↑ Brians, Paus. "Orders of Magnitude". Retrieved 9 May 2013.

- ↑ John Baez, 28 November 2012

Further reading

- Asimov, Isaac The Measure of the Universe (1983)

External links

- The Scale of the Universe 2 Interactive tool from Planck length 10−35 meters to universe size 1027

- Cosmos – an Illustrated Dimensional Journey from microcosmos to macrocosmos – from Digital Nature Agency

- Powers of 10, a graphic animated illustration that starts with a view of the Milky Way at 1023 meters and ends with subatomic particles at 10−16 meters.

- What is Order of Magnitude?

| ||||||||||||||