Orbital hybridisation

- Not to be confused with s-p mixing in Molecular Orbital theory. See Molecular orbital diagram.

In chemistry, hybridisation (or hybridization) is the concept of mixing atomic orbitals into new hybrid orbitals (with different energies, shapes, etc., than the component atomic orbitals) suitable for the pairing of electrons to form chemical bonds in valence bond theory. Hybrid orbitals are very useful in the explanation of molecular geometry and atomic bonding properties. Although sometimes taught together with the valence shell electron-pair repulsion (VSEPR) theory, valence bond and hybridisation are in fact not related to the VSEPR model.[1]

History

Chemist Linus Pauling first developed the hybridisation theory in 1931 in order to explain the structure of simple molecules such as methane (CH4) using atomic orbitals.[2] Pauling pointed out that a carbon atom forms four bonds by using one s and three p orbitals, so that "it might be inferred" that a carbon atom would form three bonds at right angles (using p orbitals) and a fourth weaker bond using the s orbital in some arbitrary direction. In reality however, methane has four bonds of equivalent strength separated by the tetrahedral bond angle of 109.5°. Pauling explained this by supposing that in the presence of four hydrogen atoms, the s and p orbitals form four equivalent combinations or hybrid orbitals, each denoted by sp3 to indicate its composition, which are directed along the four C-H bonds.[3] This concept was developed for such simple chemical systems, but the approach was later applied more widely, and today it is considered an effective heuristic for rationalising the structures of organic compounds. It gives a simple orbital picture equivalent to Lewis structures. Hybridisation theory finds its use mainly in organic chemistry.

Atomic orbitals

Orbitals are a model representation of the behaviour of electrons within molecules. In the case of simple hybridisation, this approximation is based on atomic orbitals, similar to those obtained for the hydrogen atom, the only neutral atom for which the Schrödinger equation can be solved exactly. In heavier atoms, such as carbon, nitrogen, and oxygen, the atomic orbitals used are the 2s and 2p orbitals, similar to excited state orbitals for hydrogen.

Overview

Hybrid orbitals are assumed to be mixtures of atomic orbitals, superimposed on each other in various proportions. For example, in methane, the C hybrid orbital which forms each carbon–hydrogen bond consists of 25% s character and 75% p character and is thus described as sp3 (read as s-p-three) hybridised. Quantum mechanics describes this hybrid as an sp3 wavefunction of the form N(s + √3pσ), where N is a normalization constant (here 1/2) and pσ is a p orbital directed along the C-H axis to form a sigma bond. The ratio of coefficients (denoted λ in general) is √3 in this example. Since the electron density associated with an orbital is proportional to the square of the wavefunction, the ratio of p-character to s-character is λ2 = 3. The p character or the weight of the p component is N2λ2 = 3/4.

Hybridisation schemes can also be used to represent the electron configuration in transition metals. For example, the permanganate ion (MnO4−) has sd3 hybridisation with orbitals that are 25% s and 75% d.

Types of hybridisation

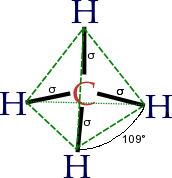

sp3

Hybridisation describes the bonding atoms from an atom's point of view. For a tetrahedrally coordinated carbon (e.g., methane CH4), the carbon should have 4 orbitals with the correct symmetry to bond to the 4 hydrogen atoms.

Carbon's ground state configuration is 1s2 2s2 2px1 2py1 or more easily read:

| C | ↑↓ | ↑↓ | ↑ | ↑ | |

| 1s | 2s | 2px | 2py | 2pz |

The carbon atom can utilize its two singly occupied p-type orbitals (the designations px py or pz are meaningless in this context, lacking order), to form two covalent bonds with two hydrogen atoms, yielding the singlet methylene CH2, the simplest carbene. The carbon atom can also bond to four hydrogen atoms by an excitation of an electron from the doubly occupied 2s orbital to the empty 2p orbital, producing four singly occupied orbitals.

| C* | ↑↓ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ |

| 1s | 2s | 2px | 2py | 2pz |

The energy released by formation of two additional bonds more than compensates for the excitation energy required, energetically favouring the formation of four C-H bonds.

Quantum mechanically, the lowest energy is obtained if the four bonds are equivalent, which requires that they be formed from equivalent orbitals on the carbon. A set of four equivalent orbitals can be obtained that are linear combinations of the valence-shell (core orbitals are almost never involved in bonding) s and p wave functions,[4] which are the four sp3 hybrids.

| C* | ↑↓ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ |

| 1s | sp3 | sp3 | sp3 | sp3 |

In CH4, four sp3 hybrid orbitals are overlapped by hydrogen 1s orbitals, yielding four σ (sigma) bonds (that is, four single covalent bonds) of equal length and strength.

translates into

sp2

Other carbon based compounds and other molecules may be explained in a similar way. For example, ethene (C2H4) has a double bond between the carbons.

For this molecule, carbon sp2 hybridises, because one π (pi) bond is required for the double bond between the carbons and only three σ bonds are formed per carbon atom. In sp2 hybridisation the 2s orbital is mixed with only two of the three available 2p orbitals,

| C* | ↑↓ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ |

| 1s | sp2 | sp2 | sp2 | 2p |

forming a total of three sp2 orbitals with one remaining p orbital. In ethylene (ethene) the two carbon atoms form a σ bond by overlapping two sp2 orbitals and each carbon atom forms two covalent bonds with hydrogen by s–sp2 overlap all with 120° angles. The π bond between the carbon atoms perpendicular to the molecular plane is formed by 2p–2p overlap. The hydrogen–carbon bonds are all of equal strength and length, in agreement with experimental data.

sp

The chemical bonding in compounds such as alkynes with triple bonds is explained by sp hybridisation. In this model, the 2s orbital is mixed with only one of the three p orbitals,

| C* | ↑↓ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ |

| 1s | sp | sp | 2p | 2p |

resulting in two sp orbitals and two remaining p orbitals. The chemical bonding in acetylene (ethyne) (C2H2) consists of sp–sp overlap between the two carbon atoms forming a σ bond and two additional π bonds formed by p–p overlap. Each carbon also bonds to hydrogen in a σ s–sp overlap at 180° angles.

Hybridisation and molecule shape

Hybridisation helps to explain molecule shape, since the angles between bonds are (approximately) equal to the angles between hybrid orbitals, as explained above for the tetrahedral geometry of methane. As another example, the three sp2 hybrid orbitals are at angles of 120° to each other, so this hybridisation favours trigonal planar molecular geometry with bond angles of 120°. Other examples are given in the table below.

| Classification | Main group | Transition metal[5][6] |

|---|---|---|

| AX2 |

|

|

| AX3 |

|

|

| AX4 |

|

|

| AX5 | - |

|

| AX6 | - |

|

Hybridisation of hypervalent molecules

Traditional description

Hybridisation is often presented for main group AX5 and above, as well as for many transition metal complexes, using the hybridisation scheme first proposed by Pauling.

| Classification | Main group | Transition metal |

|---|---|---|

| AX2 | - |

|

| AX3 | - |

|

| AX4 | - |

|

| AX5 |

|

|

| AX6 |

|

|

| AX7 |

|

|

In this notation, d orbitals of main group atoms are listed after the s and p orbitals since they have the same principal quantum number (n), while d orbitals of transition metals are listed first since the s and p orbitals have a higher n. Thus for AX5 molecules, sp3d hybridisation in the P atom involves 3s, 3p and 3d orbitals, while dsp3 for Fe involves 3d, 4s and 4p orbitals.

However, hybridisation of s, p and d orbitals together is no longer accepted, as more recent calculations based on molecular orbital theory have shown that for main group centers the d component is insignificant, while for transition metal centers the p component is insignificant.

Resonance description

As shown by computational chemistry, hypervalent molecules can be stable only given strongly polar (and weakened) bonds with electronegative ligands such as fluorine or oxygen to reduce the valence electron occupancy of the central atom to a maximum of 8[8] (or 12 for transition metals).[5] This requires an explanation that invokes sigma resonance in addition to hybridisation, which implies that each resonance structure has its own hybridisation scheme. As a guideline, all resonance structures have to obey the octet (8) rule for main group centers and the duodectet (12) rule for transition metal centers.

| Classification | Main group | Transition metal |

|---|---|---|

| AX2 | - | Linear (180°) |

| ||

| AX3 | - | Trigonal planar (120°) |

| ||

| AX4 | - | Square planar (90°) |

| ||

| AX5 | Trigonal bipyramidal (90°, 120°) | Trigonal bipyramidal (90°, 120°) |

|

| |

| AX6 | Octahedral (90°) | Octahedral (90°) |

|

| |

| AX7 | Pentagonal bipyramidal (90°, 72°) | Pentagonal bipyramidal (90°, 72°) |

|

|

Variable hybridisation

Although ideal hybrid orbitals can be useful, in reality most bonds require orbitals of intermediate character. This requires an extension to include flexible weightings of atomic orbitals of each type (s, p, d) and allows for a quantitative depiction of bond formation when the molecular geometry deviates from ideal bond angles. The amount of p-character is not restricted to integer values; i.e., hybridisations like sp2.5 are also readily described.

The hybridisation of bond orbitals is determined by Bent's rule: "Atomic s character concentrates in orbitals directed toward electropositive substituents".

Molecules with lone pairs

For molecules with lone pairs, the σ lone pair and bonding pairs hybridise to a varying extent[9] to give the molecule's bond angles. For example, the two bond-forming hybrid orbitals of oxygen in water can be described as sp4 to yield the interorbital angle of 104.5°. This means that they have 20% s character and 80% p character and does not imply that a hybrid orbital is formed from one s and four p orbitals on oxygen since the 2p subshell of oxygen only contains three p orbitals. The σ and π symmetry lone pairs are not equivalent contrary to the simplistic version taught alongside VSEPR theory (see below).

- Trigonal pyramidal (AX3E1)

- E.g., NH3

- Bent (AX2E1–2)

- The out-of-plane p-orbital can either be a lone pair or pi bond.

- E.g., SO2, H2O

- Monocoordinate (AX1E1–3)

- The two out-of-line p-orbitals can either be lone pairs or pi bonds.

- E.g., CO, SO, HF

Hypervalent molecules

For hypervalent molecules with lone pairs, the bonding scheme can be split into two components: the "resonant bonding" component and the "regular bonding" component. The "regular bonding" component has the same description (see above), while the "resonant bonding" component consists of resonating bonds utilizing p orbitals. The table below shows how each shape is related to the two components and their respective descriptions.

| Regular bonding component (marked in red) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bent | Monocoordinate | - | ||

| Resonant bonding component | Linear axis | Seesaw (AX4E1) (90°, 180°, >90°) | T-shaped (AX3E2) (90°, 180°) | Linear (AX2E3) (180°) |

|

|

| ||

| Square planar equator | - | Square pyramidal (AX5E1) (90°, 90°) | Square planar (AX4E2) (90°) | |

|

| |||

| Pentagonal planar equator | - | Pentagonal pyramidal (AX6E1) (90°, 72°) | Pentagonal planar (AX5E2) (72°) | |

|

| |||

Misconceptions

VSEPR

The simplistic version of hybridisation taught alongside VSEPR theory falls short for a few reasons.

- It inconsistently distinguishes sigma-pi symmetry.[9] For example, following the guidelines of VSEPR, the hybridization of the oxygen in water is described with two equivalent "rabbit ear" lone pairs.[10] However the distinction of σ-π symmetry implies that one of the two lone pairs is in a pure p-type orbital with its electron density perpendicular to the H–O–H framework,[9][11] while the other lone pair is in an s-rich orbital that is in the same plane as the H–O–H bonding.[9][11]

- The assumed relation of one hybrid orbital per VSEPR electron pair leads to the hypervalent spmdn hybridisation scheme above which has been superseded.

Photoelectron spectra

There is a popular misconception that the concept of hybrid orbitals incorrectly predicts the ultraviolet photoelectron spectra of many molecules. While this is true if Koopmans' theorem is applied to localized hybrids, this ignores resonance in the ionized states which reveals that the electron did not eject from a discrete hybrid orbital. For example, in methane, the ionized states (CH4+) can be constructed out of four resonance structures attributing the ejected electron to each of the four sp3 orbitals. A linear combination of these four structures, conserving the number of structures, leads to a triply degenerate T2 state and a A1 state.[12] The difference in energy between each ionized state and the ground state would be an ionization energy, which yields two values in agreement with experiment.

d orbitals in main group centers

In 1990, Magnusson published a seminal work definitively excluding the role of d-orbital hybridization in bonding in hypervalent compounds of second-row elements, ending a point of contention and confusion. Part of the confusion originates from the fact that d-functions are essential in the basis sets used to describe these compounds (or else unreasonably high energies and distorted geometries result). Also, the contribution of the d-function to the molecular wavefunction is large. These facts were incorrectly interpreted to mean that d-orbitals must be involved in bonding.[13]

p orbitals in transition metal centers

Similarly, p orbitals in transition metal centers were thought to participate in bonding with ligands, hence the 18-electron description; however, recent molecular orbital calculations have found that such p orbital participation in bonding is insignificant,[14][15] even though there is a non-negligible contribution of the p-function to the molecular wavefunction.

Hybridization theory vs. molecular orbital theory

Hybridisation theory is an integral part of organic chemistry and in general discussed together with molecular orbital theory. For drawing reaction mechanisms sometimes a classical bonding picture is needed with two atoms sharing two electrons.[16] Predicting bond angles in methane with MO theory is not straightforward. Hybridisation theory explains bonding in alkenes[17] and methane.[18]

Bonding orbitals formed from hybrid atomic orbitals may be considered as localized molecular orbitals, which can be formed from the delocalized orbitals of molecular orbital theory by an appropriate mathematical transformation. For molecules with a closed electron shell in the ground state, this transformation of the orbitals leaves the total many-electron wave function unchanged. The hybrid orbital description of the ground state is therefore equivalent to the delocalized orbital description for ground state total energy and electron density, as well as the molecular geometry that corresponds to the minimum total energy value.

See also

- Bent's rule (effect of ligand electronegativity)

- Linear combination of atomic orbitals molecular orbital method

- MO diagrams

- Ligand field theory

- Crystal field theory

- Variable hybridization

References

- ↑ Gillespie, R.J. (2004), "Teaching molecular geometry with the VSEPR model", Journal of Chemical Education 81 (3): 298–304, Bibcode:2004JChEd..81..298G, doi:10.1021/ed081p298

- ↑ Pauling, L. (1931), "The nature of the chemical bond. Application of results obtained from the quantum mechanics and from a theory of paramagnetic susceptibility to the structure of molecules", Journal of the American Chemical Society 53 (4): 1367–1400, doi:10.1021/ja01355a027

- ↑ L. Pauling The Nature of the Chemical Bond (3rd ed., Oxford University Press 1960) p.111–120.

- ↑ McMurray, J. (1995). Chemistry Annotated Instructors Edition (4th ed.). Prentice Hall. p. 272. ISBN 978-0-131-40221-8

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Weinhold, Frank; Landis, Clark R. (2005). Valency and bonding: A Natural Bond Orbital Donor-Acceptor Perspective. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 381–383, 367. ISBN 978-0-521-83128-4.

- ↑ Kaupp, Martin (2001). ""Non-VSEPR" Structures and Bonding in d(0) Systems". Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 40 (1): 3534–3565. doi:10.1002/1521-3773(20011001)40:19<3534::AID-ANIE3534>3.0.CO;2-#.

- ↑ King, R. Bruce (2000). "Atomic orbitals, symmetry, and coordination polyhedra". Coordination Chemistry Reviews 197: 141–168.

- ↑ David L. Cooper , Terry P. Cunningham , Joseph Gerratt , Peter B. Karadakov , Mario Raimondi (1994). "Chemical Bonding to Hypercoordinate Second-Row Atoms: d Orbital Participation versus Democracy". Journal of the American Chemical Society 116 (10): 4414–4426. doi:10.1021/ja00089a033.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 Allen D. Clauss, Stephen F. Nelsen, Mohamed Ayoub, John W. Moore, Clark R. Landis and Frank Weinhold (2014). "Rabbit-ears hybrids, VSEPR sterics, and other orbital anachronisms". Chemistry Education Research and Practice 15: 417–434. doi:10.1039/C4RP00057A.

- ↑ Petrucci R.H., Harwood W.S. and Herring F.G. "General Chemistry. Principles and Modern Applications" (Prentice-Hall 8th edn 2002) p. 441

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Laing, Michael (1987). "No rabbit ears on water. The structure of the water molecule: What should we tell the students?". J. Chem. Educ. 64: 124–128. doi:10.1021/ed064p124.

- ↑ Sason S. Shaik; Phillipe C. Hiberty (2008). A Chemist's Guide to Valence Bond Theory. New Jersey: Wiley-Interscience. ISBN 978-0-470-03735-5.

- ↑ E. Magnusson. Hypercoordinate molecules of second-row elements: d functions or d orbitals? J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1990, 112, 7940–7951. doi:10.1021/ja00178a014

- ↑ C. R. Landis, F. Weinhold (2007). "Valence and extra-valence orbitals in main group and transition metal bonding". Journal of Computational Chemistry 28 (1): 198–203. doi:10.1002/jcc.20492.

- ↑ O’Donnell, Mark (2012). "Investigating P-Orbital Character In Transition Metal-to-Ligand Bonding" (PDF). Brunswick, ME: Bowdoin College. Retrieved 2012-09-16.

- ↑ Clayden, Jonathan; Greeves, Nick; Warren, Stuart; Wothers, Peter (2001). Organic Chemistry (1st ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 105. ISBN 978-0-19-850346-0.

- ↑ Organic Chemistry, Third Edition Marye Anne Fox James K. Whitesell 2003 ISBN 978-0-7637-3586-9

- ↑ Organic Chemistry 3rd Ed. 2001 Paula Yurkanis Bruice ISBN 978-0-130-17858-9