Orbital eccentricity

The orbital eccentricity of an astronomical object is a parameter that determines the amount by which its orbit around another body deviates from a perfect circle. A value of 0 is a circular orbit, values between 0 and 1 form an elliptical orbit, 1 is a parabolic escape orbit, and greater than 1 is a hyperbola. The term derives its name from the parameters of conic sections, as every Kepler orbit is a conic section. It is normally used for the isolated two-body problem, but extensions exist for objects following a rosette orbit through the galaxy.

Definition

In a two-body problem with inverse-square-law force, every orbit is a Kepler orbit. The eccentricity of this Kepler orbit is a non-negative number that defines its shape.

The eccentricity may take the following values:

- circular orbit:

- elliptic orbit:

(see Ellipse)

(see Ellipse) - parabolic trajectory:

(see Parabola)

(see Parabola) - hyperbolic trajectory:

(see Hyperbola)

(see Hyperbola)

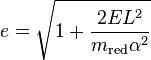

The eccentricity  is given by

is given by

where E is the total orbital energy,  is the angular momentum,

is the angular momentum,  is the reduced mass. and

is the reduced mass. and  the coefficient of the inverse-square law central force such as gravity or electrostatics in classical physics:

the coefficient of the inverse-square law central force such as gravity or electrostatics in classical physics:

( is negative for an attractive force, positive for a repulsive one) (see also Kepler problem).

is negative for an attractive force, positive for a repulsive one) (see also Kepler problem).

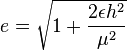

or in the case of a gravitational force:

where  is the specific orbital energy (total energy divided by the reduced mass),

is the specific orbital energy (total energy divided by the reduced mass),  the standard gravitational parameter based on the total mass, and

the standard gravitational parameter based on the total mass, and  the specific relative angular momentum (angular momentum divided by the reduced mass).

the specific relative angular momentum (angular momentum divided by the reduced mass).

For values of e from 0 to 1 the orbit's shape is an increasingly elongated (or flatter) ellipse; for values of e from 1 to infinity the orbit is a hyperbola branch making a total turn of 2 arccsc e, decreasing from 180 to 0 degrees. The limit case between an ellipse and a hyperbola, when e equals 1, is parabola.

Radial trajectories are classified as elliptic, parabolic, or hyperbolic based on the energy of the orbit, not the eccentricity. Radial orbits have zero angular momentum and hence eccentricity equal to one. Keeping the energy constant and reducing the angular momentum, elliptic, parabolic, and hyperbolic orbits each tend to the corresponding type of radial trajectory while e tends to 1 (or in the parabolic case, remains 1).

For a repulsive force only the hyperbolic trajectory, including the radial version, is applicable.

For elliptical orbits, a simple proof shows that arcsin( ) yields the projection angle of a perfect circle to an ellipse of eccentricity

) yields the projection angle of a perfect circle to an ellipse of eccentricity  . For example, to view the eccentricity of the planet Mercury (

. For example, to view the eccentricity of the planet Mercury ( =0.2056), one must simply calculate the inverse sine to find the projection angle of 11.86 degrees. Next, tilt any circular object (such as a coffee mug viewed from the top) by that angle and the apparent ellipse projected to your eye will be of that same eccentricity.

=0.2056), one must simply calculate the inverse sine to find the projection angle of 11.86 degrees. Next, tilt any circular object (such as a coffee mug viewed from the top) by that angle and the apparent ellipse projected to your eye will be of that same eccentricity.

Etymology

From Medieval Latin eccentricus, derived from Greek ekkentros "out of the center", from ek-, ex- "out of" + kentron "center". Eccentric first appeared in English in 1551, with the definition "a circle in which the earth, sun. etc. deviates from its center." Five years later, in 1556, an adjective form of the word was added.

Calculation

The eccentricity of an orbit can be calculated from the orbital state vectors as the magnitude of the eccentricity vector:

where:

is the eccentricity vector.

is the eccentricity vector.

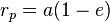

For elliptical orbits it can also be calculated from the periapsis and apoapsis since  and

and  , where

, where  is the semimajor axis.

is the semimajor axis.

where:

is the radius at apoapsis (i.e., the farthest distance of the orbit to the center of mass of the system, which is a focus of the ellipse).

is the radius at apoapsis (i.e., the farthest distance of the orbit to the center of mass of the system, which is a focus of the ellipse). is the radius at periapsis (the closest distance).

is the radius at periapsis (the closest distance).

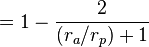

The eccentricity of an elliptical orbit can also be used to obtain the ratio of the periapsis to the apoapsis:

Examples

The eccentricity of the Earth's orbit is currently about 0.0167; the Earth's orbit is nearly circular. Over hundreds of thousands of years, the eccentricity of the Earth's orbit varies from nearly 0.0034 to almost 0.058 as a result of gravitational attractions among the planets (see graph).[1]

Mercury has the greatest orbital eccentricity of any planet in the Solar System (e=0.2056). Before 2006, Pluto was considered to be the planet with the most eccentric orbit (e=0.248). The Moon's value is 0.0549. For the values for all planets and other celestial bodies in one table, see List of gravitationally rounded objects of the Solar System.

Most of the Solar System's asteroids have orbital eccentricities between 0 and 0.35 with an average value of 0.17.[2] Their comparatively high eccentricities are probably due to the influence of Jupiter and to past collisions.

Comets have very different values of eccentricity. Periodic comets have eccentricities mostly between 0.2 and 0.7,[3] but some of them have highly eccentric elliptical orbits with eccentricities just below 1, for example, Halley's Comet has a value of 0.967. Non-periodic comets follow near-parabolic orbits and thus have eccentricities even closer to 1. Examples include Comet Hale–Bopp with a value of 0.995[4] and comet C/2006 P1 (McNaught) with a value of 1.000019.[5] As Hale–Bopp's value is less than 1, its orbit is elliptical and it will in fact return.[4] Comet McNaught has a hyperbolic orbit while within the influence of the planets, but is still bound to the Sun with an orbital period of about 105 years.[6] As of a 2010 Epoch, Comet C/1980 E1 has the largest eccentricity of any known hyperbolic comet with an eccentricity of 1.057,[7] and will leave the Solar System indefinitely.

Neptune's largest moon Triton has an eccentricity of 1.6 × 10−5,[8] the smallest eccentricity of any known body in the Solar System; its orbit is as close to a perfect circle as can be currently measured.

Mean eccentricity

The mean eccentricity of an object is the average eccentricity as a result of perturbations over a given time period. Neptune currently has an instant (current Epoch) eccentricity of 0.0113,[9] but from 1800 A.D. to 2050 A.D. has a mean eccentricity of 0.00859.[10]

Climatic effect

Orbital mechanics require that the duration of the seasons be proportional to the area of the Earth's orbit swept between the solstices and equinoxes, so when the orbital eccentricity is extreme, the seasons that occur on the far side of the orbit (aphelion) can be substantially longer in duration. Today, northern hemisphere fall and winter occur at closest approach (perihelion), when the earth is moving at its maximum velocity—while the opposite occurs in the southern hemisphere. As a result, in the northern hemisphere, fall and winter are slightly shorter than spring and summer—but in global terms this is balanced with them being longer below the equator. In 2006, the northern hemisphere summer was 4.66 days longer than winter and spring was 2.9 days longer than fall.[11] Apsidal precession slowly changes the place in the Earth's orbit where the solstices and equinoxes occur (this is not the precession of the axis). Over the next 10,000 years, northern hemisphere winters will become gradually longer and summers will become shorter. Any cooling effect in one hemisphere is balanced by warming in the other—and any overall change will, however, be counteracted by the fact that the eccentricity of Earth's orbit will be almost halved, reducing the mean orbital radius and raising temperatures in both hemispheres closer to the mid-interglacial peak.

See also

References

- ↑ A. Berger & M.F. Loutre (1991). "Graph of the eccentricity of the Earth's orbit". Illinois State Museum (Insolation values for the climate of the last 10 million years). Retrieved 2009-12-17.

- ↑ Asteroids

- ↑ Lewis, John (2 December 2012). Physics and Chemistry of the Solar System. Academic Press. Retrieved 2015-03-29.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 "JPL Small-Body Database Browser: C/1995 O1 (Hale-Bopp)" (2007-10-22 last obs). Retrieved 2008-12-05.

- ↑ "JPL Small-Body Database Browser: C/2006 P1 (McNaught)" (2007-07-11 last obs). Retrieved 2009-12-17.

- ↑ "Comet C/2006 P1 (McNaught) - facts and figures". Perth Observatory in Australia. 2007-01-22. Retrieved 2011-02-01.

- ↑ "JPL Small-Body Database Browser: C/1980 E1 (Bowell)" (1986-12-02 last obs). Retrieved 2010-03-22.

- ↑ David R. Williams (22 January 2008). "Neptunian Satellite Fact Sheet". NASA. Retrieved 2009-12-17.

- ↑ Williams, David R. (2007-11-29). "Neptune Fact Sheet". NASA. Retrieved 2009-12-17.

- ↑ "Keplerian elements for 1800 A.D. to 2050 A.D.". JPL Solar System Dynamics. Retrieved 2009-12-17.

- ↑ This information is concerning the summer of the year 2006 not the current year we are in now.

Prussing, John E., and Bruce A. Conway. Orbital Mechanics. New York: Oxford University Press, 1993.

External links

- World of Physics: Eccentricity

- The NOAA page on Climate Forcing Data includes (calculated) data from Berger (1978), Berger and Loutre (1991). Laskar et al. (2004) on Earth orbital variations, Includes eccentricity over the last 50 million years and for the coming 20 million years.

- The orbital simulations by Varadi, Ghil and Runnegar (2003) provides series for Earth orbital eccentricity and orbital inclination.

- Kepler's Second law's simulation

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||