Orbit (anatomy)

- This article is about the orbit, the anatomical space that contains the eye. For other uses of orbit or orbita see Orbit (disambiguation) and Orbita (disambiguation).

| Orbit | |

|---|---|

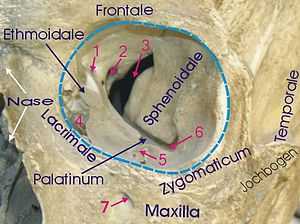

Image of the right orbit, containing the eye. | |

| Details | |

| Latin | Orbita |

| Identifiers | |

| Gray's | p.188 |

| MeSH | A02.835.232.781.324.690 |

| Dorlands /Elsevier | 12594914 |

| TA | A02.1.00.067 |

| FMA | 53074 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

In anatomy, the orbit is the cavity or socket of the skull in which the eye and its appendages are situated. "Orbit" can refer to the bony socket,[1] or it can also be used to imply the contents.[2] In the adult human, the volume of the orbit is 30 mL, of which the eye occupies 6.5 mL.[3]

Structure

The orbits are conical or four-sided pyramidal cavities, which open into the midline of the face and point back into the head. Each consists of a base, an apex and four walls. [4]

The apex lies near the medial end of superior orbital fissure and contains the optic canal (containing the optic nerve and ophthalmic artery), which communicates with middle cranial fossa.

The roof (superior wall) is formed primarily by the orbital plate frontal bone, and also the lesser wing of sphenoid near the apex of the orbit. The orbital surface presents medially by trochlear fovea and laterally by lacrimal fossa.[5]

The floor (inferior wall) is formed by the orbital surface of maxilla, the orbital surface of zygomatic bone and the minute orbital process of palatine bone. Medially, near the orbital margin, is located the groove for nasolacrimal duct. Near the middle of the floor, located infraorbital groove, which leads to the infraorbital foramen. The floor is separated from the lateral wall by inferior orbital fissure, which connects the orbit to pterygopalatine and infratemporal fossa.

The medial wall is formed primarily by the orbital plate of ethmoid, as well as contributions from the frontal process of maxilla, the lacrimal bone, and a small part of the body of the sphenoid. It is the thinnest wall of the orbit, evidenced by pneumatized ethmoidal cells.[5]

The lateral wall is formed by the frontal process of zygomatic and more posteriorly by the orbital plate of the greater wing of sphenoid. The bones meet at the zygomaticosphenoid suture. The lateral wall is the thickest wall of the orbit, important because it is the most exposed surface, highly vulnerable to blunt force trauma.

Borders

The base, which opens in the face, has four borders. The following bones take part in their formation:

- Superior margin: frontal bone and sphenoid

- Inferior margin: maxilla, palatine and zygomatic

- Medial margin: ethmoid, lacrimal bone, and frontal

- Lateral margin: zygomatic and sphenoid

Contents

- Eye

- Fascias: Orbital, Bulbar

- Extraocular muscles (Levator Palpebrae Superioris; Superior, Inferior, Lateral and Medial Rectus muscles; Superior and Inferior oblique muscles)

- Nerves: cranial nerves II, III, IV, V, and VI

- Blood vessels

- Extraocular Fat

- Lacrimal gland, lacrimal sac, nasolacrimal duct

- Eyelids

- Medial palpebral ligament and lateral palpebral ligament

- Medial and Lateral check ligaments

- Suspensory ligament of the eyeball

- Conjunctiva

- Trochlea of superior oblique

- Orbital septum

- Ciliary ganglion and short ciliary nerves

Bones

yellow = Frontal bone

green = Lacrimal bone

brown = Ethmoid bone

blue = Zygomatic bone

purple = Maxillary bone

aqua = Palatine bone

red = Sphenoid bone

teal = Nasal bone (illustrated but not part of the orbit)

In humans, seven bones make up the bony orbit:

- Frontal bone (Pars orbitalis)

- Lacrimal bone

- Ethmoid bone (Lamina papyracea)

- Zygomatic bone (Orbital process of the zygomatic bone)

- Maxillary bone (Orbital surface of the body of the maxilla)

- Palatine bone (Orbital process of palatine bone)

- Sphenoid bone (Greater and lesser wings)

Foramina and openings

- Optic canal

- Superior orbital fissure

- Inferior orbital fissure

- Anterior ethmoidal foramen

- Posterior ethmoidal foramen

- Infraorbital foramen

- Supraorbital foramen

- Naso-lacrimal canal opening

- Zygomatic orbital foramen

Function

The orbits protect the eye from mechanical injury.[6]

Clinical significance

In the orbit, fat tissue, which surrounds the eyeball and its muscles, keeps the rotation smooth with respect to the center of the eye. If excess fat or other abnormal tissue is collected in the orbit, the eye may protrude, a condition known as exophthalmos.[7]

a. tear gland / lacrimal gland,

b. superior lacrimal punctum,

c. superior lacrimal canal,

d. tear sac / lacrimal sac,

e. inferior lacrimal punctum,

f. inferior lacrimal canal,

g. nasolacrimal canal

Enlargement of the lacrimal gland, located superotemporally within the orbit, produces protrusion of the eye inferiorly and medially (away from the location of the lacrimal gland). Lacrimal gland may be enlarged from inflammation (e.g. sarcoid) or neoplasm (e.g. lymphoma or adenoid cystic carcinoma).[8]

Tumors (e.g. glioma and meningioma of the optic nerve) within the cone formed by the horizontal rectus muscles produce axial protrusion (bulging forward) of the eye.

Graves disease may also cause axial protrusion of the eye, known as Graves' ophthalmopathy, due to buildup of extracellular matrix proteins and fibrosis in the rectus muscles. Development of Graves' ophthalmopathy may be independent of thyroid function.[9]

Additional images

-

Orbita

-

Orbita

-

The skull from the front

-

Medial wall of left orbit

-

Dissection showing origins of right ocular muscles, and nerves entering by the superior orbital fissure

-

Coronal section of nasal cavities

-

-

Lateral orbit nerves

-

Orbital cavity

-

-

Extrinsic eye muscle. Nerves of orbita. Deep dissection.

-

Extrinsic eye muscle. Nerves of orbita. Deep dissection.

-

Extrinsic eye muscle. Nerves of orbita. Deep dissection.

-

Extrinsic eye muscle. Nerves of orbita. Deep dissection.

-

Extrinsic eye muscle. Nerves of orbita. Deep dissection.

References

- ↑ "Orbit – Definition and More from the Free Merriam-Webster Dictionary". Retrieved 2010-03-26.

- ↑ Orbit at the US National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- ↑ Duane's Ophthalmology, Chapter 32 Embryology and Anatomy of the Orbit and Lacrimal System. (eds Tasman W, Jaeger EA) Lippincott/Williams & Wilkins, 2007

- ↑ "eye, human."Encyclopædia Britannica from Encyclopædia Britannica 2006 Ultimate Reference Suite DVD 2009

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Moore, Keith L. (2010). Clinically Oriented Anatomy 6th Ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 978-07817-7525-0.

- ↑ "eye, human."Encyclopædia Britannica from Encyclopædia Britannica 2006 Ultimate Reference Suite DVD 2009

- ↑ "eye, human

- ↑ Kumar V, Abbas AK, Fausto N. Robbins and Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease. Seventh Edition. Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders, 2005, p. 1423.

- ↑ Hatton MP, Rubin PA. The pathophysiology of thyroid-associated ophthalmopathy. Ophthalmol Clin North Am 15:113–119, 2002.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Orbit (anatomy). |

- oph/2 at eMedicine – "Arterial Supply, Orbit"

- Anatomy photo:29:os-0501 at the SUNY Downstate Medical Center

- Atlas image: eye_5 at the University of Michigan Health System

- Atlas image: rsa2p4 at the University of Michigan Health System

- Interactive tutorial at anatome.ncl.ac.uk

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||