Oradour-sur-Glane

The village of Oradour-sur-Glane in Haute-Vienne in Nazi occupied France was destroyed on 10 June 1944, when 642 of its inhabitants, including women and children, were massacred by a German Waffen-SS company. A new village was built after the war on a nearby site, but on the orders of the then French president, Charles de Gaulle, the original has been maintained as a permanent memorial and museum.

Background

In February 1944, 2nd SS Panzer Division ("Das Reich") was stationed in the Southern French town of Valence-d'Agen,[1] north of Toulouse, waiting to be resupplied with new equipment and freshly trained troops. After the D-Day invasion of Normandy, the division was ordered to make its way across the country to stop the Allied advance. One of the division's units was the 4th SS Panzer Grenadier Regiment ("Der Führer"). Its staff included SS-Standartenführer Sylvester Stadler as regimental commander, SS-Sturmbannführer Adolf Diekmann as commander of the regiment's 1st Battalion and SS-Sturmbannführer Otto Weidinger, who was designated Stadler's successor as regimental commander and was with the regiment for familiarisation purposes. Command of "Der Führer" passed from Stadler to Weidinger on 14 June.[2]

Early on the morning of 10 June 1944, Diekmann informed Weidinger at regimental headquarters that he had been approached by two members of the Milice, a paramilitary force belonging to the Vichy Regime. They claimed that a Waffen-SS officer was being held by the Resistance in Oradour-sur-Vayres, a nearby village. The captured German was alleged to be SS-Sturmbannführer Helmut Kämpfe, commander of the 2nd SS Panzer Reconnaissance Battalion (another unit of the "Das Reich" division), who may have been captured by the Maquis du Limousin the day before. Stadler ordered Diekmann to have the mayor of the town name thirty people who could serve as hostages in exchange for Kämpfe.

Massacre

On 10 June, Diekmann's battalion sealed off Oradour-sur-Glane and ordered all the townspeople – and anyone who happened to be in or near the town – to assemble in the village square, ostensibly to have their identity papers examined. In addition to the residents of the village, the SS also apprehended six people who did not live there but had the misfortune to be riding their bikes through the village when the Germans arrived.

All the women and children were locked in the church while the village was looted. Meanwhile, the men were led to six barns and sheds where machine guns were already in place.

According to the account of a survivor, the soldiers began shooting at them, aiming for their legs so that they would die slowly. Once the victims were no longer able to move, the soldiers covered their bodies with fuel and set the barns on fire. Only six men escaped; one of them was later seen walking down a road heading for the cemetery and was shot dead. In all, 190 men perished.

The soldiers proceeded to the church and placed an incendiary device there. After it was ignited, women and children tried to escape through the doors and windows of the church, but they were met with machine-gun fire. A total of 247 women and 205 children died in the carnage. Only 47-year-old Marguerite Rouffanche survived. She slid out by a rear sacristy window, followed by a young woman and child.[3] All three were shot; Marguerite Rouffanche was wounded and her companions were killed. She crawled to some pea bushes behind the church, where she remained hidden overnight until she was rescued the following morning. Another group of about twenty villagers had fled Oradour-sur-Glane as soon as the soldiers had appeared. That night, the village was partially razed.

A few days later, survivors were allowed to bury the dead. 642 inhabitants of Oradour-sur-Glane had been murdered in a matter of hours. Adolf Diekmann claimed that the episode was a just retaliation for partisan activity in nearby Tulle and the kidnapping of Helmut Kämpfe.

Murphy report

Raymond J. Murphy, a 20-year-old American B-17 navigator shot down over Avord, France in late April, 1944, seems to have witnessed the aftermath of the massacre.[4] After being hidden by the French Resistance, Murphy was flown to England on 6 August, and in debriefing filled in a questionnaire on 7 August and made several drafts of a formal report.[4] The version finally submitted on 15 August has a handwritten addendum:[5]

- About 3 weeks ago, I saw a town within 4 hours bicycle ride up [sic] the Gerbeau farm [of Resistance leader Camille Gerbeau] where some 500 men, women, and children had been murdered by the Germans. I saw one baby who had been crucified.

Murphy's report was made public in 2011 after a Freedom of Information Act request by his grandson, an attorney in the United States Department of Justice National Security Division.[4] It is the only account to mention crucifying a baby.[4] Shane Harris concludes the addendum is a true statement by Murphy and that the town, not named in Murphy's report, is very likely Oradour-sur-Glane.[4]

German response

Protests at Diekmann's supposedly unilateral action followed, from Generalfeldmarschall Erwin Rommel; General Gleiniger, German commander in Limoges; and the Vichy government. SS-Standartenführer Stadler felt Diekmann had far exceeded his orders and began a judicial investigation. Diekmann, 29 years old, was killed in action shortly afterwards during the Battle of Normandy, and a large number of the third company, which had committed the massacre, were themselves killed in action within a few days, and the investigation was suspended.

Numerous other instances of Nazi use of collective punishment and massacre of civilians are documented across occupied Europe.

Postwar trials

On 12 January 1953, a military tribunal in Bordeaux heard the case against the surviving 65 of the approximately 200 German soldiers who had been involved. Only 21 of them were present, as many were living in East Germany, which would not allow them to be extradited. Seven of them were Germans, but 14 were Alsatians, French nationals of German ethnicity who had been regarded by the Nazis as members of the Reich. All but one of them claimed to have been drafted into the Waffen-SS by force. Such forced conscripts from Alsace and Lorraine called themselves the malgré-nous, meaning "against our will".

The trial caused a huge protest in Alsace, forcing the French authorities to split the tribunal into two separate proceedings, according to the nationality of the defendants. On 11 February, 20 defendants were found guilty. Continuing uproar (including calls for autonomy) in Alsace pressed the French parliament to pass an amnesty law for all the malgré-nous on 19 February, and the convicted Alsatians were released shortly afterwards. This, in turn, caused bitter protests in the Limousin region.

By 1958, all the German defendants had been released as well. General Heinz Lammerding of the Das Reich division, who had given the orders for the measures against the Resistance, died in 1971 after a successful entrepreneurial career. At the time of the trial he lived in Düsseldorf, which was located inside the British occupation zone of West Germany, and the French government never obtained his extradition from the British authorities.[6]

The last trial against a former Waffen-SS member took place in 1983. Shortly before, former SS-Obersturmführer Heinz Barth was tracked down in the German Democratic Republic. Barth participated in the Oradour-sur-Glane massacre as a platoon leader in the "Der Führer" regiment, in charge of 45 soldiers. He was one of several war criminals charged with giving orders to shoot 20 men in a garage. Barth was sentenced to life imprisonment by the First Senate of the City Court of Berlin. He was released from prison in the reunified Germany in 1997, and he died in August 2007.

On 8 January 2014, Werner Christukat,[7] an 88-year-old former member of the 3rd Company of the 1st Battalion of the "Der Führer" SS regiment was charged, by the state court in Cologne, with 25 charges of murder and hundreds of counts of accessory to murder in connection with the massacre in Oradour-sur-Glane.[8] The suspect, who was identified only as Werner C., had until 31 March 2014 to respond to the charges. If the case went to trial, it could have possibly been held in a juvenile court because the suspect was only 19 at the time. According to his attorney, Rainer Pohlen, the suspect acknowledges being at the village but denies being involved in any killings.[9] On 9 December 2014, the court dropped the case citing a lack of any witness statements or reliable documentary evidence able to disprove the suspect's contention that he was not a part of the massacre.[10]

Memorial

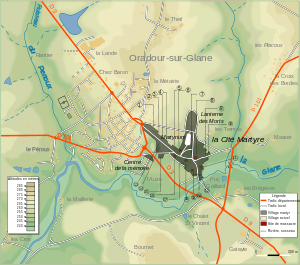

After the war, General Charles de Gaulle decided the village should never be rebuilt, but would remain a memorial to the cruelty of the Nazi occupation.

The new village of Oradour-sur-Glane (population 2,188 in 2006), northwest of the site of the massacre, was built after the war. The ruins of the original village remain as a memorial to the dead and to represent similar sites and events.

In 1999 French president Jacques Chirac dedicated a memorial museum, the Centre de la mémoire d'Oradour, near the entrance to the Village Martyr ("martyred village"). Its museum includes items recovered from the burned-out buildings: watches stopped at the time their owners were burned alive, glasses melted from the intense heat, and various personal items.

On 6 June 2004, at the commemorative ceremony of the Normandy invasion in Caen, German chancellor Gerhard Schröder pledged that Germany would not forget the Nazi atrocities and specifically mentioned Oradour-sur-Glane.

On 4 September 2013, German president Joachim Gauck and French president François Hollande visited the ghost village of Oradour-sur-Glane. A joint news conference broadcast by the two leaders followed their tour of the site.[11] This was the first time a German president had come to the site of one of the biggest World War II massacres on French soil.[11]

In popular culture

Television

The story of Oradour-sur-Glane was featured in 1974 in the noted British documentary television series The World at War, which was narrated by Sir Laurence Olivier. The first and final episodes (1 and 26, entitled "A New Germany" and "Remember" respectively) show helicopter views of the destroyed village, interspersed with pictures of the victims that appear on their graves. Episodes 1 and 26 both started with the words:

Down this road, on a summer day in 1944 ... The soldiers came. Nobody lives here now. They stayed only a few hours. When they had gone, the community which had lived for a thousand years ... was dead.

This is Oradour-sur-Glane, in France. The day the soldiers came, the people were gathered together. The men were taken to garages and barns, the women and children were led down this road ... and they were driven ... into this church. Here, they heard the firing as their men were shot. Then . . . they were killed too. A few weeks later, many of those who had done the killing were themselves dead, in battle.

They never rebuilt Oradour. Its ruins are a memorial. Its martyrdom stands for thousands upon thousands of other martyrdoms in Poland, in Russia, in Burma, in China, in a World at War ...

And at the end of episode 26, while another aerial shot of the village ruins plus photos of various massacre victims were being shown to the accompaniment of dramatic and moving music, which is taken from the St Nicholas Mass by Haydn, Olivier said:

At the village of Oradour-sur-Glane, the day the soldiers came, they killed more than six hundred men, women ... and children. Remember.

This is also referenced in the 2010 series World War II in Color in the episode "OVERLORD", which aired on 7 January 2010.

Film

- A feature film, Oradour, was released in September 2011 in France.

- The 1975 French film Le vieux fusil, is based on these facts.[12]

Literature

- The poet Gillian Clarke, National Poet for Wales, commemorates the massacre at Oradour-sur-Glane in two poems from her 2009 collection A Recipe for Water,[13] 'Oradour-sur-Glane' and 'Singer'.

- In the Dark Horse Comics Grendel Tales miniseries "The Devil's Hammer", five 'Grendel' knights massacre and horribly mutilate all but two of the inhabitants of a town named 'Oradour', possibly in homage to Oradour-sur-Glane.

- A novel "A High and Hidden Place", by Michele Claire Lucas, is the story of a young woman's search for her family, lost at the massacre. HarperCollins Publishers 2005

Music

- In the video for The Streets' "The Escapist", Mike Skinner is briefly seen walking through the destroyed village of Oradour-sur-Glane.

- A photo of a wrecked car in the village (see above) is the basis of the cover of the album Tochka opory (Точка Опоры) by the Russian group Skafandr and Vasya V. from Kirpichi.[14]

- Band Silent Planet has a song entitled "Tiny Hands (Au Revoir)" which was written about the event

Gallery

-

The main street of Oradour-sur-Glane

-

The church where the women and children were burnt to death

-

Wrecked hardware – bicycles, sewing machines etc. are still left in Oradour-sur-Glane

-

New village Oradour-sur-Glane

-

Entrance of the memorial museum

See also

|

References

Notes

- ↑ (French) « Rubrique Valence d'Agen », Archives du Tarn-et-Garonne, 11 June 2011.

- ↑ "Order of Battle for Das Reich as of June 1944". Oradour.info. 9 June 1944. Retrieved 24 November 2012.

- ↑ Farmer, Sarah (1999). "Martyred Village". The New York Times.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 Harris, Shane (June 5, 2014). "The Massacre at Oradour-sur-Glane: An American lawyer finds new evidence about one of World War II’s most notorious war crimes, seven decades after D-Day". Foreign Policy.

- ↑ Murphy, Raymond J., 2d Lt., U.S.A.C. (1944). "Evasion in France" (PDF). E&E Report No. 866.

- ↑ Farmer, Sarah. Oradour : arrêt sur mémoire, Paris, Calmann-Lévy, 1994, pp. 30–34

- ↑ Smale, Alison (9 December 2014). "German Court Finds Lack of Proof Tying Ex-Soldier to Nazi Massacre". New York Times. Retrieved 12 December 2014.

- ↑ Smale, Alison. "In Germany, Former SS Man, 88, Charged With Wartime Mass Murder". New York Times. Retrieved 10 January 2014.

- ↑ Rising, David (8 January 2014). "88-Year-Old Charged in Nazi-Era Massacre". ABC News. Associated Press. Retrieved 11 January 2014.

- ↑ "Court drops case against German over WWII French village massacre". Retrieved 9 December 2014.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Olivennes, Hannah. "German president visits site of Nazi massacre in France". France 24 International News. Retrieved 4 September 2013.

- ↑ http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0073864/

- ↑ Clarke, Gillian (2009)A Recipe for Water, Carcanet (Manchester), pp. 59–60

- ↑ press-reliz (Russian)

Bibliography

- Farmer, Sarah. Martyred Village: Commemorating the 1944 Massacre at Oradour-sur-Glane. University of California Press, 2000.

- Fouché, Jean-Jacques. Massacre At Oradour: France, 1944; Coming To Grips With Terror, Northern Illinois University Press, 2004.

- INSEE

- Penaud, Guy. La "Das Reich" 2e SS Panzer Division (Parcours de la division en France, 560 pp), Éditions de La Lauze/Périgueux. ISBN 2-912032-76-8

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Oradour-sur-Glane. |