Optic equation

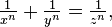

In number theory, the optic equation[1] is an equation that requires the sum of the reciprocals of two positive integers a and b to equal the reciprocal of a third positive integer c:

Multiplying both sides by abc shows that the optic equation is equivalent to a Diophantine equation (a polynomial equation in multiple integer variables).

Solution

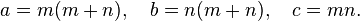

All solutions in integers a, b, c are given in terms of positive integer parameters m, n by[1]

In particular, every number c forms part of a solution with m = 1 and n = c. The solution generated by a pair m and n will have the property that the greatest common divisor of a, b, and c is 1 if and only if m and n are coprime.

Appearances in geometry

The optic equation, permitting but not requiring integer solutions, appears in several contexts in geometry.

In the crossed ladders problem,[2] two ladders braced at the bottoms of vertical walls cross at the height h and lean against the opposite walls at heights of A and B. We have  Moreover, the formula continues to hold if the walls are slanted and all three measurements are made parallel to the walls.

Moreover, the formula continues to hold if the walls are slanted and all three measurements are made parallel to the walls.

Let P be a point on the circumcircle of an equilateral triangle ABC, on the minor arc AB. Let a be the distance from P to A and b be the distance from P to B. On a line passing through P and the far vertex C, let c be the distance from P to the triangle side AB. Then[3]:p. 172

In a trapezoid, draw a segment parallel to the two parallel sides, passing through the intersection of the diagonals and having endpoints on the non-parallel sides. Then if we denote the lengths of the parallel sides as a and b and half the length of the segment through the diagonal intersection as c, the sum of the reciprocals of a and b equals the reciprocal of c.[4]

The special case in which the integers whose reciprocals are taken must be square numbers appears in the context of right triangles: the sum of the reciprocals of the squares of the altitudes from the legs (equivalently, of the squares of the legs themselves) equals the reciprocal of the square of the altitude from the hypotenuse. This holds whether or not the numbers are integers; there is a formula (see here) that generates all integer cases.[5][6]

Relation to Fermat's Last Theorem

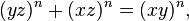

Fermat's Last Theorem states that the sum of two integers each raised to the same integer power n cannot equal another integer raised to the power n if n > 2. This implies that no solutions to the optic equation have all three integers equal to perfect powers with the same power n > 2. For if  then multiplying through by

then multiplying through by  would give

would give  which is impossible by Fermat's Last Theorem.

which is impossible by Fermat's Last Theorem.

See also

- Erdős–Straus conjecture, a different Diophantine equation involving sums of reciprocals of integers

- Sums of reciprocals

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Dickson, L. E., History of the Theory of Numbers, Volume II: Diophantine Analysis, Chelsea Publ. Co., 1952, pp. 688–691.

- ↑ Gardner, M. Mathematical Circus: More Puzzles, Games, Paradoxes and Other Mathematical Entertainments from Scientific American. New York: Knopf, 1979, pp. 62–64.

- ↑ Posamentier, Alfred S., and Salkind, Charles T., Challenging Problems in Geometry, Dover Publ., 1996.

- ↑ GoGeometry, , Accessed 2012-07-08.

- ↑ Voles, Roger, "Integer solutions of a−2+b−2=d−2," Mathematical Gazette 83, July 1999, 269–271.

- ↑ Richinick, Jennifer, "The upside-down Pythagorean Theorem," Mathematical Gazette 92, July 2008, 313–317.