Operator norm

In mathematics, the operator norm is a means to measure the "size" of certain linear operators. Formally, it is a norm defined on the space of bounded linear operators between two given normed vector spaces.

Introduction and definition

Given two normed vector spaces V and W (over the same base field, either the real numbers R or the complex numbers C), a linear map A : V → W is continuous if and only if there exists a real number c such that

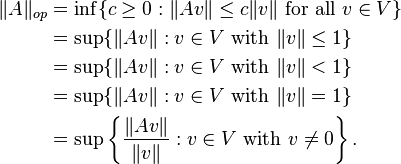

(the norm on the left is the one in W, the norm on the right is the one in V). Intuitively, the continuous operator A never "lengthens" any vector more than by a factor of c. Thus the image of a bounded set under a continuous operator is also bounded. Because of this property, the continuous linear operators are also known as bounded operators. In order to "measure the size" of A, it then seems natural to take the smallest number c such that the above inequality holds for all v in V. In other words, we measure the "size" of A by how much it "lengthens" vectors in the "biggest" case. So we define the operator norm of A as

(the minimum exists as the set of all such c is closed, nonempty, and bounded from below).[1]

Examples

Every real m-by-n matrix yields a linear map from Rn to Rm. One can put several different norms on these spaces, as explained in the article on norms. Each such choice of norms gives rise to an operator norm and therefore yields a norm on the space of all m-by-n matrices. Examples can be found in the article on matrix norms.

If we specifically choose the Euclidean norm on both Rn and Rm, then we obtain the matrix norm which to a given matrix A assigns the square root of the largest eigenvalue of the matrix A*A (where A* denotes the conjugate transpose of A). This is equivalent to assigning the largest singular value of A.

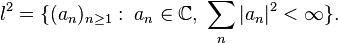

Passing to a typical infinite-dimensional example, consider the sequence space  defined by

defined by

This can be viewed as an infinite-dimensional analogue of the Euclidean space Cn. Now take a bounded sequence s = (sn ). The sequence s is an element of the space l ∞, with a norm given by

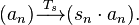

Define an operator Ts by simply multiplication:

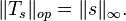

The operator T s is bounded with operator norm

One can extend this discussion directly to the case where l 2 is replaced by a general Lp space with p > 1 and l∞ replaced by L∞.

Equivalent definitions

One can show that the following definitions are all equivalent:

Properties

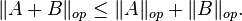

The operator norm is indeed a norm on the space of all bounded operators between V and W. This means

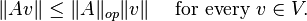

The following inequality is an immediate consequence of the definition:

The operator norm is also compatible with the composition, or multiplication, of operators: if V, W and X are three normed spaces over the same base field, and A : V → W and B: W → X are two bounded operators, then

For bounded operators on V, this implies that operator multiplication is jointly continuous.

It follows from the definition that a sequence of operators converge in operator norm means they converge uniformly on bounded sets.

Table of common operator norms

Some common operator norms are easy to calculate, and others are NP-hard. Except for the NP-hard norms, all these norms can be calculated in N^2 operations (for a NxN matrix), with the exception of the l2-l2 norm (which requires N^3 operations for the exact answer, or less if you approximate it with the power method or Lanczos iterations).

| Co-domain | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

| ||

| Domain |  |

Maximum  norm of a column norm of a column | Maximum  of a column of a column | Maximum absolute entry of matrix |

|

NP-hard | Maximum singular value | Maximum  of a row of a row | |

|

NP-hard | NP-hard | Maximum  norm of a row norm of a row | |

Operators on a Hilbert space

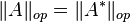

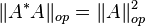

Suppose H is a real or complex Hilbert space. If A : H → H is a bounded linear operator, then we have

and

where A* denotes the adjoint operator of A (which in Euclidean Hilbert spaces with the standard inner product corresponds to the conjugate transpose of the matrix A).

In general, the spectral radius of A is bounded above by the operator norm of A:

To see why equality may not always hold, consider the Jordan canonical form of a matrix in the finite-dimensional case. Because there are non-zero entries on the superdiagonal, equality may be violated. The quasinilpotent operators is one class of such examples. A nonzero quasinilpotent operator A has spectrum {0}. So ρ(A) = 0 while ||A||op > 0.

However, when a matrix N is normal, its Jordan canonical form is diagonal (up to unitary equivalence); this is the spectral theorem. In that case it is easy to see that

The spectral theorem can be extended to normal operators in general. Therefore the above equality holds for any bounded normal operator N. This formula can sometimes be used to compute the operator norm of a given bounded operator A: define the Hermitian operator B = A*A, determine its spectral radius, and take the square root to obtain the operator norm of A.

The space of bounded operators on H, with the topology induced by operator norm, is not separable. For example, consider the Hilbert space L2[0,1]. For 0 < t ≤ 1, let Ωt be the characteristic function of [0,t], and Pt be the multiplication operator given by Ωt, i.e.

Then each Pt is a bounded operator with operator norm 1 and

But {Pt} is an uncountable set. This implies the space of bounded operators on L2[0,1] is not separable, in operator norm. One can compare this with the fact that the sequence space l ∞ is not separable.

The set of all bounded operators on a Hilbert space, together with the operator norm and the adjoint operation, yields a C*-algebra.

See also

- operator algebra

- topologies on the set of operators on a Hilbert space

- matrix norm

Notes

- ↑ See e.g. Lemma 6.2 of Aliprantis & Border (2007), which treats the proof of existence of the minimum as an easy exercise.

- ↑ section 4.3.1, Joel Tropp's PhD thesis,

References

- Aliprantis, Charalambos D.; Border, Kim C. (2007), Infinite Dimensional Analysis: A Hitchhiker's Guide, Springer, p. 229, ISBN 9783540326960.

- Conway, John B. (1990), "III.2 Linear Operators on Normed Spaces", A Course in Functional Analysis, New York: Springer-Verlag, pp. 67–69, ISBN 0-387-97245-5