Operation Downfall

| Operation Downfall | |

|---|---|

| |

| Objective | Invasion of Japan |

| Outcome | Canceled after Japan surrendered on 15 August 1945 |

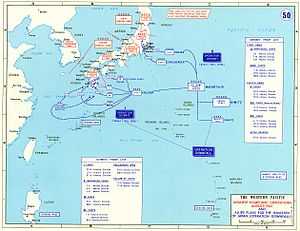

Operation Downfall was the codename for the Allied plan for the invasion of Japan near the end of World War II. The planned operation was abandoned when Japan surrendered following the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The operation had two parts: Operation Olympic and Operation Coronet. Set to begin in October 1945, Operation Olympic was intended to capture the southern third of the southernmost main Japanese island, Kyūshū, with the recently captured island of Okinawa to be used as a staging area. Later, in spring 1946, Operation Coronet was the planned invasion of the Kantō Plain, near Tokyo, on the Japanese island of Honshū. Airbases on Kyūshū captured in Operation Olympic would allow land-based air support for Operation Coronet. If Downfall had taken place, it would have been the largest amphibious operation in human history.[1]

Japan's geography made this invasion plan quite obvious to the Japanese as well; they were able to predict the Allied invasion plans accurately and thus adjust their defensive plan, Operation Ketsugō, accordingly. The Japanese planned an all-out defense of Kyūshū, with little left in reserve for any subsequent defense operations. Casualty predictions varied widely but were extremely high. Depending on the degree to which Japanese civilians resisted the invasion, estimates ran into the millions for Allied casualties.[2]

Planning

Responsibility for planning Operation Downfall fell to the U.S. commanders: Fleet Admiral Chester Nimitz, General of the Army Douglas MacArthur and the Joint Chiefs of Staff—Fleet Admirals Ernest King and William D. Leahy, and Generals of the Army George Marshall and Hap Arnold (the latter was commander of the US Army Air Forces).[3] Douglas MacArthur at the time was also being considered for promotion to a special "super rank" of General of the Armies, so as to be granted operational authority over other five star officers.[4] However, the proposal to promote MacArthur was only at the level of informal discussion by the time World War II ended.

At the time, the development of the atomic bomb was a very closely guarded secret (not even then Vice President Harry Truman knew of its existence until he later became President), known only to a few top officials outside the Manhattan Project and the initial planning for the invasion of Japan did not take its existence into consideration. Once the atomic bomb became available, General Marshall envisioned using it to support the invasion, if sufficient numbers could be produced in time.[5]

Throughout the Pacific War, the Allies were unable to agree on a single Commander-in-Chief (C-in-C). Allied command was divided into regions: by 1945, for example, Chester Nimitz was Allied C-in-C Pacific Ocean Areas, while Douglas MacArthur was Supreme Allied Commander, South West Pacific Area, and Admiral Louis Mountbatten was Supreme Allied Commander, South East Asia Command. A unified command was deemed necessary for an invasion of Japan. Interservice rivalry over who it should be (the US Navy wanted Nimitz, but the US Army wanted MacArthur) was so serious that it threatened to derail planning. Ultimately, the Navy partially conceded, and MacArthur was to have total command of all forces, if circumstances made it necessary.[6]

Considerations

The primary considerations that the planners had to deal with were time and casualties—how they could force Japan's surrender as quickly as possible, with as few Allied casualties as possible. Prior to the Quebec Conference, 1943, a joint British-American planning team produced a plan ("Appreciation and Plan for the Defeat of Japan") which did not call for an invasion of the Japanese home islands until 1947–48.[7][8] The American Joint Chiefs of Staff believed that prolonging the war to such an extent was dangerous for national morale. Instead, at the Quebec conference, the Combined Chiefs of Staff agreed that Japan should be forced to surrender not more than one year after Germany's surrender.

The US Navy urged the use of blockade and airpower to bring about Japan's capitulation. They proposed operations to capture airbases in nearby Shanghai, China, and Korea, which would give the US Army Air Forces a series of forward airbases from which to bombard Japan into submission.[9] The US Army, on the other hand, argued that such a strategy could "prolong the war indefinitely" and expend lives needlessly, and therefore that an invasion was necessary. They supported mounting a large-scale thrust directly against the Japanese homeland, with none of the side operations that the Navy had suggested. Ultimately, the Army's viewpoint won.[10]

Physically, Japan made an imposing target, distant from other landmasses and with very few beaches geographically suitable for sea-borne invasion. Only Kyūshū (the southernmost island of Japan) and the beaches of the Kantō plain (both southwest and southeast of Tokyo) were realistic invasion zones. The Allies decided to launch a two-stage invasion. Operation Olympic would attack southern Kyūshū. Airbases would be established, which would give cover for Operation Coronet, the attack on Tokyo Bay.

Assumptions

While the geography of Japan was known, the US military planners had to estimate the defending forces that they would face. Based on intelligence available early in 1945, their assumptions included the following:[11]

- "That operations in this area will be opposed not only by the available organized military forces of the Empire, but also by a fanatically hostile population."[11]

- "That approximately three (3) hostile divisions will be disposed in Southern KYUSHU and an additional three (3) in Northern KYUSHU at initiation of the OLYMPIC operation."[11]

- "That total hostile forces committed against KYUSHU operations will not exceed eight (8) to ten (10) divisions and that this level will be speedily attained."[11]

- "That approximately twenty-one (21) hostile divisions, including depot divisions, will be on HONSHU at initiation of [Coronet] and that fourteen (14) of these divisions may be employed in the KANTO PLAIN area."[11]

- "That the enemy may withdraw his land-based air forces to the Asiatic Mainland for protection from our neutralizing attacks. That under such circumstances he can possibly amass from 2,000 to 2,500 planes in that area by exercise of rigid economy, and that this force can operate against KYUSHU landings by staging through homeland fields."[11]

Olympic

Operation Olympic, the invasion of Kyūshū, was to begin on "X-Day", which was scheduled for 1 November 1945. The combined Allied naval armada would have been the largest ever assembled, including 42 aircraft carriers, 24 battleships, and 400 destroyers and destroyer escorts. Fourteen US divisions were scheduled to take part in the initial landings. Using Okinawa as a staging base, the objective would have been to seize the southern portion of Kyūshū. This area would then be used as a further staging point to attack Honshū in Operation Coronet.

Olympic was also to include a deception plan, known as Operation Pastel. Pastel was designed to convince the Japanese that the Joint Chiefs had rejected the notion of a direct invasion and instead were going to attempt to encircle and bombard Japan. This would require capturing bases in Formosa, along the Chinese coast, and in the Yellow Sea area.[12]

The Twentieth Air Force was to have continued its role as the main Allied strategic bomber force used against the Japanese home islands. Tactical air support was to be the responsibility of the U.S. Far East Air Forces (FEAF)—a formation which comprised the Fifth, Seventh and Thirteenth Air Forces—during the preparation for the invasion. FEAF was responsible for attacking Japanese airfields and transportation arteries on Kyūshū and Southern Honshū (e.g. the Kanmon Tunnel) and for attaining and maintaining air superiority over the beaches.

Before the main invasion, the offshore islands of Tanegashima, Yakushima, and the Koshikijima Islands were to be taken, starting on X-5.[13] The invasion of Okinawa had demonstrated the value of establishing secure anchorages close at hand, for ships not needed off the landing beaches and for ships damaged by air attack.

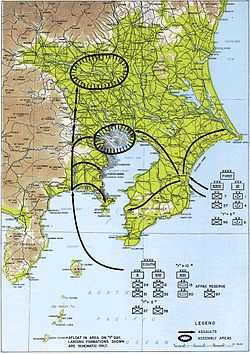

Kyūshū was to be invaded by U.S. Sixth Army at three points: Miyazaki, Ariake, and Kushikino. If a clock were drawn on a map of Kyūshū, these points would roughly correspond to 4, 5, and 7 o'clock, respectively. The 35 landing beaches were all named for automobiles: Austin, Buick, Cadillac through Stutz, Winton, and Zephyr.[14] With one corps assigned to each landing, the invasion planners assumed that the Americans would outnumber the Japanese by roughly three to one. In early 1945, Miyazaki was virtually undefended, while Ariake with its nearby good harbor was heavily defended.

The invasion was not supposed to conquer the entire island, just the southernmost third of it, as indicated by the dashed line on the map, "general limit of northern advance". Southern Kyūshū would offer a staging ground and a valuable airbase for Operation Coronet.

Coronet

Operation Coronet, the invasion of Honshū at the Kantō Plain south of the capital, was to begin on "Y-Day", which was scheduled for March 1, 1946. Coronet would have been even larger than Olympic, with 25 divisions, including the floating reserve, earmarked for the initial operations. (The Overlord invasion of Normandy, by comparison, had 12 divisions in the initial landings.) The U.S. First Army would have invaded at Kujūkuri Beach, on the Bōsō Peninsula, while U.S. Eighth Army invaded at Hiratsuka, on Sagami Bay. Both armies would then drive north and inland, meeting at Tokyo.

Redeployment

Olympic was to be mounted with resources already present in the Pacific, including the British Pacific Fleet, a Commonwealth formation that included at least eighteen aircraft carriers (and providing 25% of the Allied air power) and four battleships. The Australian First Tactical Air Force took part in the campaign to retake the Philippines. These would likely have augmented US close air support units over Japan. The only major re-deployment for Olympic was Tiger Force, a Commonwealth long range heavy bomber unit, made up of 10 squadrons scheduled to be transferred from RAF Bomber Command control in Europe to airbases on Okinawa. This would have included 617 Squadron, the specialist 'Dam Busters' who were armed with the massive ground penetrator 'Grand Slams'. In 1944, British plans had allowed for 500–1,000 heavy bombers, this had been reduced to 22 squadrons of RAF, RCAF and other nations and by 1945 to 10 from the RAF, RCAF, RNZAF and RAAF.

If reinforcements had been needed for Olympic, they could have been provided from forces being assembled for Coronet, which would have needed the redeployment of substantial Allied forces from Europe, South Asia, Australasia, and elsewhere. These would have included the U.S. First Army (15 divisions) and the Eighth Air Force, which were in Europe. The redeployment was complicated by the simultaneous partial demobilization of the U.S. Army, which drastically reduced the divisions' combat effectiveness, by stripping them of their most experienced officers and men.

According to U.S. historian John Ray Skates,

American planners took no note [initially] of the possibility that [non-U.S.] Allied ground troops might participate in the invasion of the Kanto Plain. The published plans indicated that assault, followup, and reserve units would all come from US forces. [However, as] the Coronet plans were being refined during the [northern] summer of 1945, all the major Allied countries offered ground forces, and a debate developed at the highest levels of command over the size, mission, equipment, and support of these contingents.[15]

The Australian government requested the inclusion of Australian Army units in the first wave of Olympic, but this was rejected by US commanders.[16] Following negotiations among the western Allied powers, it was decided that a Commonwealth Corps, initially made up of infantry divisions from the Australian, British and Canadian armies would be used in Coronet. Reinforcements would have been available from those countries, as well as other parts of the Commonwealth. MacArthur blocked proposals to include an Indian Army division, because of differences in language, organization, composition, equipment, training, and doctrine.[17][18] He also recommended that the corps should be organized along the lines of a US corps, should use only US equipment and logistics, and should train in the US for six months before deployment; these suggestions were accepted.[17] A British officer, Lieutenant-General Sir Charles Keightley, had been nominated to lead the Commonwealth Corps. The Australian government questioned the appointment of an officer with no experience fighting the Japanese, and suggested that Lieutenant General Leslie Morshead, an Australian who had been carrying out the New Guinea and Borneo campaigns, should be appointed.[19] The war ended before the details of the corps were finalized.

Operation Ketsugō

Meanwhile, the Japanese had their own plans. Initially, they were concerned about an invasion during the summer of 1945. However, the Battle of Okinawa went on for so long that they concluded the Allies would not be able to launch another operation before the typhoon season, during which the weather would be too risky for amphibious operations. Japanese intelligence predicted fairly closely where the invasion would take place: southern Kyūshū at Miyazaki, Ariake Bay, and/or the Satsuma Peninsula.[20]

While Japan no longer had a realistic prospect of winning the war, Japan's leaders believed they could make the cost of conquering Japan too high for the Allies to accept, which would lead to some sort of armistice rather than total defeat. The Japanese plan for defeating the invasion was called Operation Ketsugō (決号作戦 ketsugō sakusen) ("Operation Codename Decisive"). The Japanese were secretly constructing an underground headquarters in Matsushiro, Nagano Prefecture, which could be used in the event of Allied invasion to shelter the Emperor and the Imperial General Staff.

Kamikaze

Admiral Matome Ugaki was recalled to Japan in February 1945 and given command of the Fifth Air Fleet on Kyūshū. The Fifth Air Fleet was assigned the task of kamikaze attacks against ships involved in the invasion of Okinawa, Operation Ten-Go, and began training pilots and assembling aircraft for the defense of Kyūshū where the Allies were likely to invade next.

The Japanese defense relied heavily on kamikaze planes. In addition to fighters and bombers, they reassigned almost all of their trainers for the mission, trying to make up in quantity what they lacked in quality. Their army and navy had more than 10,000 aircraft ready for use in July (and would have had somewhat more by October) and were planning to use almost all that could reach the invasion fleets. Ugaki also oversaw building of hundreds of small suicide boats that would also be used to attack any Allied ships that came near the shores of Kyūshū.

Fewer than 2,000 kamikaze planes launched attacks during the Battle of Okinawa, achieving approximately one hit per nine attacks. At Kyūshū, because of the more favorable circumstances (such as terrain that would reduce the Allies radar advantage), they hoped to get one for six by overwhelming the US defenses with large numbers of kamikaze attacks in a period of hours. The Japanese estimated that the planes would sink more than 400 ships; since they were training the pilots to target transports rather than carriers and destroyers, the casualties would be disproportionately greater than at Okinawa. One staff study estimated that the kamikazes could destroy a third to half of the invasion force before its landings.[21]

Naval forces

By August 1945, the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) had ceased to be an effective fighting force. The only major Japanese warships in fighting order were six aircraft carriers, four cruisers, and one battleship, none of which could be adequately fueled: while the Japanese still had a sizeable number of minor warships their use would also have been limited by lack of fuel. The Japanese could "sustain a force of twenty operational destroyers and perhaps forty submarines for a few days at sea."[22]

The IJN also had about 100 Kōryū-class midget submarines, 250 smaller Kairyū-class midget submarines, 400 Kaiten manned torpedoes, and 800 Shin'yō suicide boats.

Ground forces

In any amphibious operation, the defender has two options for defensive strategy: strong defense of the beaches or defense in depth. Early in the war (such as at Tarawa), the Japanese employed strong defenses on the beaches with little or no manpower in reserve. This tactic proved to be very vulnerable to pre-invasion shore bombardment. Later in the war, at Peleliu, Iwo Jima, and Okinawa, the Japanese switched strategy and dug in their forces in the most defensible terrain.

For the defense of Kyūshū, the Japanese took an intermediate posture, with the bulk of their defensive forces a few kilometers inland from the shore: back far enough to avoid complete exposure to naval gunnery but close enough that the Americans could not establish a secure foothold before engaging them. The counteroffensive forces were still farther back, prepared to move against whichever landing seemed to be the main effort.

In March 1945, there was only one combat division in Kyūshū. Over the next four months, the Imperial Japanese Army transferred forces from Manchuria, Korea, and northern Japan, while raising other forces in place. By August, they had 14 divisions and various smaller formations, including three tank brigades, for a total of 900,000 men.[23] Although the Japanese were able to raise large numbers of new soldiers, equipping them was more difficult. By August, the Japanese Army had the equivalent of 65 divisions in the homeland but only enough equipment for 40 and only enough ammunition for 30.[24]

The Japanese did not formally decide to stake everything on the outcome of the Battle of Kyūshū, but they concentrated their assets to such a degree that there would be little left in reserve. By one estimate, the forces in Kyūshū had 40% of all the ammunition in the Home Islands.[25]

In addition, the Japanese had organized the Patriotic Citizens Fighting Corps, which included all healthy men aged 15 to 60 and women 17 to 40 for a total of 28 million people, for combat support and, later, combat jobs. Weapons, training, and uniforms were generally lacking: some men were armed with nothing better than muzzle-loading muskets, longbows, or bamboo spears; nevertheless, they were expected to make do with what they had.[26][27] One mobilized high school girl, Yukiko Kasai, found herself issued an awl and told, "Even killing one American soldier will do. ... You must aim for the abdomen."[28]

Allied re-evaluation of Olympic

Air threat

US military intelligence initially estimated the number of Japanese aircraft to be around 2,500.[29] The Okinawa experience was bad: almost two fatalities and a similar number wounded per sortie—and Kyūshū was likely to be worse. To attack the ships off Okinawa, Japanese planes had to fly long distances over open water; to attack the ships off Kyūshū, they could fly overland and then short distances out to the landing fleets. Gradually, intelligence learned that the Japanese were devoting all their aircraft to the kamikaze mission and taking effective measures to conserve them until the battle. An Army estimate in May was 3,391 planes; in June, 4,862; in August, 5,911. A Navy estimate, abandoning any distinction between training and combat aircraft, in July was 8,750; in August, 10,290.[30]

The Allies made counter-kamikaze preparations, known as the Big Blue Blanket. This involved adding more fighter squadrons to the carriers in place of torpedo and dive bombers, and converting B-17s into airborne radar pickets in manner similar to modern-day AWACS. Nimitz came up with a plan for a pre-invasion feint, sending a fleet to the invasion beaches a couple of weeks before the real invasion, to lure out the Japanese on their one-way flights, who would then find—instead of the valuable, vulnerable transports—ships loaded with anti-aircraft guns from bow to stern.

The main defense against Japanese air attacks would have come from the massive fighter forces that were being assembled in the Ryukyu Islands. US Army Fifth and Seventh Air Force and US Marine air units had moved into the islands immediately after the invasion, and air strength had been increasing in preparation for the all-out assault on Japan. In preparation for the invasion, an air campaign against Japanese airfields and transportation arteries had commenced before the Japanese surrender.

Ground threat

Through April, May, and June, Allied intelligence followed the buildup of Japanese ground forces, including five divisions added to Kyūshū, with great interest but some complacency, still projecting that in November the total for Kyūshū would be about 350,000 servicemen. That changed in July, with the discovery of four new divisions and indications of more to come. By August, the count was up to 600,000, and Magic cryptanalysis had identified nine divisions in southern Kyūshū—three times the expected number and still a serious underestimate of actual Japanese strength.

Estimated troop strength in early July was 350,000,[31] rising to 545,000 in early August.[32]

The intelligence revelations about Japanese preparations on Kyushu emerging in mid-July transmitted powerful shock waves both in the Pacific and in Washington. On 29 July, [MacArthur's intelligence chief, Major General Charles A.] Willoughby... noted first that the April estimate allowed for the Japanese capability to deploy six divisions on Kyushu, with the potential to deploy ten. "These [six] divisions have since made their appearance, as predicted," he observed, "and the end is not in sight." If not checked, this threatened "to grow to [the] point where we attack on a ratio of one (1) to one (1) which is not the recipe for victory."[33]

The build-up of Japanese troops on Kyūshū led American war planners, most importantly General George Marshall, to consider drastic changes to Olympic, or replacing it with a different plan for invasion.

Chemical weapons

Because of its predictable wind patterns and several other factors, Japan was particularly vulnerable to gas attacks. Such attacks would neutralize the Japanese tendency to fight from caves, which would increase the soldiers' exposure to gas.

Although chemical warfare had been outlawed by the Geneva Protocol, neither the US nor Japan were signatories at the time. While the US had promised never to initiate gas warfare, Japan had used gas against the Chinese earlier in the war.[34]

Fear of Japanese retaliation [to chemical weapon use] lessened because by the end of the war Japan's ability to deliver gas by air or long-range guns had all but disappeared. In 1944 Ultra revealed that the Japanese doubted their ability to retaliate against United States use of gas. 'Every precaution must be taken not to give the enemy cause for a pretext to use gas,' the commanders were warned. So fearful were the Japanese leaders that they planned to ignore isolated tactical use of gas in the home islands by the US forces because they feared escalation.[35]

Nuclear weapons

On Marshall's orders, Major General John E. Hull looked into the tactical use of nuclear weapons for the invasion of the Japanese home islands (even after the dropping of two strategic atomic bombs on Japan, Marshall did not think that the Japanese would capitulate immediately). Colonel Lyle E. Seeman reported that at least seven Fat Man type plutonium implosion bombs would be available by X-Day, which could be dropped on defending forces. Seeman advised that American troops not enter an area hit by a bomb for "at least 48 hours"; the risk of nuclear fallout was not well understood, and such a short amount of time after detonation would have resulted in substantial radiation exposure for the American troops.[36]

Ken Nichols, the District Engineer of the Manhattan Engineer District, wrote that at the beginning of August 1945, "[p]lanning for the invasion of the main Japanese home islands had reached its final stages, and if the landings actually took place, we might supply about fifteen atomic bombs to support the troops."[37] An air burst 1,800–2,000 ft (550–610 m) above the ground had been chosen for the (Hiroshima) bomb to achieve maximum blast effects, and to minimize residual radiation on the ground as it was hoped that American troops would soon occupy the city.[38]

Alternative targets

The Joint Staff planners, taking note of the extent to which the Japanese had concentrated on Kyūshū at the expense of the rest of Japan, considered alternate places to invade such as the island of Shikoku, northern Honshū at Sendai, or Ominato. They also considered skipping the preliminary invasion and going directly at Tokyo.[39] Attacking northern Honshū would have the advantage of a much weaker defense but had the disadvantage of giving up land-based air support (except the B-29s) from Okinawa.

Prospects for Olympic

General Douglas MacArthur dismissed any need to change his plans:

I am certain that the Japanese air potential reported to you as accumulating to counter our OLYMPIC operation is greatly exaggerated. [...] As to the movement of ground forces [...] I do not credit [...] the heavy strengths reported to you in southern Kyushu. [...] In my opinion, there should not be the slightest thought of changing the Olympic operation.[40]

However, Admiral Ernest King, the Chief of Naval Operations, was prepared to oppose proceeding with the invasion, with Admiral Nimitz's concurrence, which would have set off a major dispute within the US government.

At this juncture, the key interaction would likely have been between Marshall and Truman. There is strong evidence that Marshall remained committed to an invasion as late as 15 August. [...] But tempering Marshall's personal commitment to invasion would have been his comprehension that civilian sanction in general, and Truman's in particular, was unlikely for a costly invasion that no longer enjoyed consensus support from the armed services.[41]

Soviet intentions

Unknown to the Americans, the Soviets also considered invading a major Japanese island - Hokkaido - by the end of August 1945, which would have put pressure on the Allies to act sooner than November.

In the early years of World War II, the Soviets had planned on building a huge navy in order to catch up with the Western World. However, the German invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941 forced the suspension of this plan: the Soviets had to divert most of their resources to fighting the Germans - primarily on land - throughout most of the war, leaving their navy relatively poorly equipped.[42][43][44] As a result, in Project Hula (1945), the United States transferred about 100 naval vessels (out of 180 planned) to the Soviet Union in preparation for the planned Soviet entry into the war against Japan. The transferred vessels included amphibious assault ships.

At the Yalta Conference (February 1945), the Allies had agreed that the USSR would take the southern part of the island of Sakhalin (the Soviets already controlled the northern part of the island pursuant to the Treaty of Portsmouth of 1905) which the Russian Empire had relinquished to Japan after the 1904-1905 Russo-Japanese War; and the Kuril Islands, which the settlement of the borders between Russia and Japan made in the 1875 Treaty of St. Petersburg had assigned to Japan. On the other hand, no agreement envisaged Soviet participation in the invasion of Japan itself.

The Japanese had kamikaze aircraft in southern Honshu and Kyushu which would have opposed Operations Olympic and Coronet. It is unknown to what extent they could oppose Soviet landings in the far north of Japan. For comparative purposes: approximately 1,300 Western Allied ships deployed during the Battle of Okinawa (April-June 1945). In total, 368 ships — including 120 amphibious craft — were badly damaged while another 28 — including 15 landing ships and 12 destroyers — were sunk; mostly by kamikazes. The Soviets, however, had fewer than 400 ships (most of them not equipped for amphibious assault) by the time they declared war on Japan on 8 August 1945.[45]

For Operation Downfall, the US military envisaged requiring more than 30 divisions for a successful invasion of the Japanese home islands. In comparison, the Soviet Union had about 11 divisions available; comparable to the 14 divisions the US estimated it would require to invade southern Kyushu. The Soviet invasion of the Kuril Islands (18 August - 1 September 1945) took place after Japan's capitulation on 15 August; despite this, the Japanese forces in these islands resisted quite fiercely (although some of them proved unwilling to fight due to Japan's surrender on 15 August). In the Battle of Shumshu (18-23 August 1945), the Soviets had 8,821 troops unsupported by tanks and without larger warships. The well-established Japanese garrison had 8,500 troops and fielded around 77 tanks. The Battle of Shumshu lasted for five days in which the Soviets lost over 516 troops and five of the 16 landing ships (most of these ships ex-U.S. Navy) to Japanese coastal artillery while the Japanese lost over 256 troops. Soviet casualties during the Battle of Shumshu totalled up to 1,567 while the Japanese suffered 1,018 casualties, making Shumshu the only battle in the 1945 Soviet-Japanese War where Russian losses exceeded the Japanese, in stark contrast to overall Soviet-Japanese casualty rates in land-based fighting in Manchuria.

During World War II the Japanese had a naval base at Paramushiro in the Kuril Islands and several bases in Hokkaido. Since Japan and the Soviet Union maintained a state of wary neutrality until the Soviets' declaration of war on Japan in August 1945, Japanese observers based in Japanese-held territories in Manchuria, Korea, Sakhalin, and the Kuril Islands constantly watched the port of Vladivostok and other seaports in the Soviet Union.[46]

According to Thomas B. Allen and Norman Polmar, the Soviets had carefully drawn up detailed plans for the Far East invasions, except that the landing for Hokkaido "existed in detail" only in Stalin's mind and that it was "unlikely that Stalin had interests in taking Manchuria and even taking on Hokkaido. Even if he wanted to grab as much territory in Asia as possible, he was too much focused on establishing a blockhead in Europe more so than Asia."[47]

Estimated casualties

Because the U.S. military planners assumed "that operations in this area will be opposed not only by the available organized military forces of the Empire, but also by a fanatically hostile population",[11] high casualties were thought to be inevitable, but nobody knew with certainty how high. Several people made estimates, but they varied widely in numbers, assumptions, and purposes, which included advocating for and against the invasion. Afterwards, they were reused in the debate over the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Casualty estimates were based on the experience of the preceding campaigns, drawing different lessons:

- In a letter sent to Gen. Curtis LeMay from Gen. Lauris Norstad, when LeMay assumed command of the B-29 force on Guam, Norstad told LeMay that if an invasion took place, it would cost the US "half a million" dead.[48]

- In a study done by the Joint Chiefs of Staff in April, the figures of 7.45 casualties/1,000 man-days and 1.78 fatalities/1,000 man-days were developed. This implied that a 90-day Olympic campaign would cost 456,000 casualties, including 109,000 dead or missing. If Coronet took another 90 days, the combined cost would be 1,200,000 casualties, with 267,000 fatalities.[49]

- A study done by Adm. Nimitz's staff in May estimated 49,000 U.S casualties in the first 30 days, including 5,000 at sea.[50] A study done by General MacArthur's staff in June estimated 23,000 US casualties in the first 30 days and 125,000 after 120 days.[51] When these figures were questioned by General Marshall, MacArthur submitted a revised estimate of 105,000, in part by deducting wounded men able to return to duty.[52]

- In a conference with President Truman on June 18, Marshall, taking the Battle of Luzon as the best model for Olympic, thought the Americans would suffer 31,000 casualties in the first 30 days (and ultimately 20% of Japanese casualties, which implied a total of 70,000 casualties).[53] Adm. Leahy, more impressed by the Battle of Okinawa, thought the American forces would suffer a 35% casualty rate (implying an ultimate toll of 268,000).[54] Admiral King thought that casualties in the first 30 days would fall between Luzon and Okinawa, i.e., between 31,000 and 41,000.[54] Of these estimates, only Nimitz's included losses of the forces at sea, though kamikazes had inflicted 1.78 fatalities per kamikaze pilot in the Battle of Okinawa,[55] and troop transports off Kyūshū would have been much more exposed.

- A study done for Secretary of War Henry Stimson's staff by William Shockley estimated that conquering Japan would cost 1.7–4 million American casualties, including 400,000–800,000 fatalities, and five to ten million Japanese fatalities. The key assumption was large-scale participation by civilians in the defense of Japan.[2]

Outside the government, well-informed civilians were also making guesses. Kyle Palmer, war correspondent for the Los Angeles Times, said half a million to a million Americans would die by the end of the war. Herbert Hoover, in a memorandums submitted to Truman and Stimson, also estimated 500,000 to 1,000,000 fatalities, and those were believed to be conservative estimates; but it is not known if Hoover discussed these specific figures in his meetings with Truman. The chief of the Army Operations division thought them "entirely too high" under "our present plan of campaign."[56]

The Battle of Okinawa ran up 72,000 US casualties in 82 days, of whom 12,510 were killed or missing (this is conservative, because it excludes several thousand US soldiers who died after the battle indirectly, from their wounds.) The entire island of Okinawa is 464 sq mi (1,200 km2). If the US casualty rate during the invasion of Japan had been only 5% as high per unit area as it was at Okinawa, the US would still have lost 297,000 soldiers (killed or missing).

Nearly 500,000 Purple Heart medals (awarded for combat casualties) were manufactured in anticipation of the casualties resulting from the invasion of Japan; the number exceeded that of all American military casualties of the 65 years following the end of World War II, including the Korean and Vietnam Wars. In 2003, there were still 120,000 of these Purple Heart medals in stock.[57] There were so many in surplus that combat units in Iraq and Afghanistan were able to keep Purple Hearts on-hand for immediate award to soldiers wounded on the field.[57]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Mac Arthur, "13", Reports 1, US: Army.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Frank, p. 340.

- ↑ Skates, p. 18.

- ↑ Giangreco, p. .

- ↑ Perret, as cited in: Silkett, p. 119

- ↑ Skates, pp. 55–57.

- ↑ Skates, p. 37.

- ↑ Spector, pp. 276–77.

- ↑ Skates, pp. 44–50.

- ↑ Skates, pp. 53–54.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 11.5 11.6 Sutherland, p. 2.

- ↑ Skates, p. 160.

- ↑ Skates, p. 184.

- ↑ Beach Organization for Operation against Kyushu; from COMPHIBSPAC OP PLAN A11-45, August 10, 1945. Skates, pictorial insert.

- ↑ Skates, p. 229.

- ↑ Day, p. 297.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Day, p. 299.

- ↑ Skates, p. 230.

- ↑ Horner, p. .

- ↑ Skates, p. 102.

- ↑ Frank, p. 184–185.

- ↑ Feifer, p. 418.

- ↑ Frank, p. 203.

- ↑ Frank, p. 176.

- ↑ Frank, p. 177.

- ↑ Frank, pp. 188–89.

- ↑ Bauer & Coox.

- ↑ Frank, p. 189.

- ↑ Frank, p. 206.

- ↑ Frank, pp. 209–210.

- ↑ MacEachin, p. 16 (GIF), Figure 2, Estimated Japanese Dispositions on Kyushu, 9 July 1945.

- ↑ MacEachin, p. 18 (GIF), Figure 3, Estimated Japanese Dispositions on Kyushu, 2 August 1945.

- ↑ Frank, p. 211, Willoughby's Amendment 1 to "G-2 Estimate of the Enemy Situation with Respect to Kyushu".

- ↑ Skates, p. 84.

- ↑ Skates, p. 97.

- ↑ Frank, pp. 312–13.

- ↑ Nichols, p. 201.

- ↑ Nichols, pp. 175, 198, 223.

- ↑ Frank, pp. 273–274.

- ↑ Frank, pp. 274–75.

- ↑ Frank, p. 357.

- ↑ The End of the Pacific War: Reappraisals. Stanford University Press. March 1, 2007. p. 89. Retrieved 26 April 2013.

- ↑ Japanese Defence: The Search for Political Power. Allen & Unwin. pp. 48–60.

- ↑ Thomas B. Allen and Norman Polmar. Code-Name Downfall: The Secret Plan to Invade Japan-And Why Truman Dropped the Bomb. Simon & Schuster. pp. 180–185.

- ↑ Jane's Fighting Ships of World War II. Random House. pp. 180–185.

- ↑ Code-Name Downfall: The Secret Plan to Invade Japan-And Why Truman Dropped the Bomb. Simon & Schuster. pp. 115–120.

- ↑ Code-Name Downfall: The Secret Plan to Invade Japan-And Why Truman Dropped the Bomb. Simon & Schuster. pp. 168–175.

- ↑ Coffey, p. 474.

- ↑ Frank, pp. 135–137.

- ↑ Frank, p. 137.

- ↑ Frank, pp. 137–138.

- ↑ Frank, p. 138.

- ↑ Frank, pp. 140–141.

- ↑ 54.0 54.1 Frank, p. 142.

- ↑ Frank, p. 182.

- ↑ Frank, p. 122.

- ↑ 57.0 57.1 Giangreco & Moore.

References

- Allen, Thomas B.; Polmar, Norman (1995). Code-Name Downfall. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-684-80406-4.

- Bauer, Jack; Coox, Alvin D. (August 1965). "Olympic vs Ketsu-Go". Marine Corps Gazette 49 (8).

- Coffey, Thomas M. (1988). Iron Eagle: The Turbulent Life of General Curtis LeMay. New York: Avon Books. ISBN 978-0-380-70480-4.

- Day, David (1992). Reluctant Nation: Australia and the Allied Defeat of Japan, 1942–1945. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-553242-5.

- Drea, Edward J. (1998). "Japanese Preparations for the Defense of the Homeland & Intelligence Forecasting for the Invasion of Japan". In the Service of the Emperor: Essays on the Imperial Japanese Army. Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-1708-9.

- Feifer, George (2001). The Battle of Okinawa: The Blood and the Bomb. Guilford, CT: The Lyons Press. ISBN 978-1-58574-215-8.

- Frank, Richard B. (1999). Downfall: The End of the Imperial Japanese Empire. New York: Random House. ISBN 978-0-679-41424-7.

- Giangreco, Dennis M. (2009). Hell to Pay: Operation Downfall and the Invasion of Japan, 1945–1947. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-59114-316-1.

- ———; Moore, Kathryn (December 1, 2003). "Are New Purple Hearts Being Manufactured to Meet the Demand?". History News Network. Retrieved December 4, 2006.

- Glantz, David (Spring 1995). "The Soviet Invasion of Japan". Quarterly Journal of Military History 7 (3).

- Horner, David (1982). High Command. Sydney: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 978-0-86861-076-4.

- MacEachin, Douglas J. (December 1998). "The Final Months of the War With Japan: Signals Intelligence, U.S. Invasion Planning, and the A-Bomb Decision". CIA Center for the Study of Intelligence. Retrieved October 4, 2007.

- Nichols, Kenneth (1987). The Road to Trinity: A Personal Account of How America's Nuclear Policies Were Made. New York: Morrow. ISBN 978-0-688-06910-0.

- Perret, Geoffrey (1991). There's A War to be Won. New York: Random House.

- Silkett, Wayne A (1994). "Downfall: The Invasion that Never Was" (PDF) (Autumn). Retrieved September 5, 2012.

- Skates, John Ray (1994). The Invasion of Japan: Alternative to the Bomb. Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-87249-972-0.

- Spector, Ronald H. (1985). Eagle Against the Sun: The American War with Japan. Random House. ISBN 978-0-394-74101-7.

- Sutherland, Richard K. et al. (28 May 1945). ""DOWNFALL": Strategic Plan for Operations in the Japanese Archipelago". Retrieved December 4, 2006.

- Thomas, Evan (March 2007). "The Last Kamikaze". World War II Magazine: 28.

- Tillman, Barrett (2007). LeMay. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 224. ISBN 978-1-4039-7135-7.

External links

- Allen, Thomas B., "Operation Downfall". Houghton Mifflin Reader's Companion to Military History.

- Bauer, K. Jack, "Operation Downfall: Olympic, Coronet; World War II in the Pacific, The Invasion of Japan". ww2pacific.com.

- Giangreco, Dennis M., "Casualty Projections for the U.S. Invasions of Japan, 1945–1946: Planning and Policy Implications"; Journal of Military History (July 1997)

- ——— (16 February 1998), Operation Downfall: US Plans and Japanese Counter-measures (transcript), US Army Command and General Staff College.

- Hoyt, Austin, American Experience: Victory in the Pacific; PBS documentary.

- Japanese Monograph No. 23, "Waiting for the invasion" (notes on Japanese preparations for an American invasion)

- Pearlman, Michael D., "Unconditional Surrender, Demobilization, and the Atomic Bomb"; Combat Studies Institute, U.S. Army Command and General Staff College, 1996.

- White, HV, The Japanese Plans for the Defense of Kyushu; 31 December 1945 (link to PDF), OCLC.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||