Operation Banner

Operation Banner was the operational name for the British Armed Forces' operation in Northern Ireland from August 1969 to July 2007. It was initially deployed at the request of the unionist government of Northern Ireland to support the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC). After the 1998 Belfast Agreement, the operation was gradually scaled down. Its role was to assert the authority of the government of the United Kingdom in Northern Ireland.

The main opposition to the British military's deployment came from the Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA). It waged a guerrilla campaign against the British military from 1970 to 1997. An internal British Army document released in 2007 stated that, whilst it had failed to defeat the IRA,[2][3] it had made it impossible for the IRA to win through violence,[2][4] and had also reduced substantially the death toll in the last years of conflict.[3]

Role of the armed forces

The support to the police forces was primarily from the British Army, with the Royal Air Force providing helicopter support as required. A maritime component was supplied under the codename of Operation Grenada, by the Royal Navy and Royal Marines in direct support of the Army commitment. This was tasked with interdicting the supply of weapons and munitions to paramilitaries, acting as a visible deterrence by maintaining a conspicuous maritime presence on and around the coast of Northern Ireland and Lough Neagh.[5]

The role of the armed forces in their support role to the police was defined by the Army in the following terms:

- "Routine support — Includes such tasks as providing protection to the police in carrying out normal policing duties in areas of terrorist threat; patrolling around military and police bases to deter terrorist attacks and supporting police-directed counter-terrorist operations"

- "Additional support — Assistance where the police have insufficient assets of their own; this includes the provision of observation posts along the border and increased support during times of civil disorder. The military can provide soldiers to protect and, if necessary, supplement police lines and cordons. The military can provide heavy plant to remove barricades and construct barriers, and additional armoured vehicles and helicopters to help in the movement of police and soldiers"

- "Specialist support — Includes bomb disposal, search and tracker dogs, and divers from the Royal Engineers"

Number of troops deployed

At the peak of the operation in the 1970s, the British Army was deploying around 21,000 soldiers. By 1980, the figure had dropped to 11,000, with a lower presence of 9,000 in 1985. The total climbed again to 10,500 after the intensification of the IRA use of barrack busters toward the end of the 1980s. In 1992, there were 17,750 members of all British military forces taking part in the operation. The British Army build-up comprised three brigades under the command of a lieutenant-general. There were six resident battalions deployed for a period of two and a half years and four roulement battalions serving six-months tours.[6] In July 1997, during the course of fierce riots in nationalist areas triggered by the Drumcree conflict, the total number of security forces in Northern Ireland increased to more than 30,000 (including the RUC).[7]

Equipment

Armoured vehicles:

- Snatch Land Rover

- Ferret armoured car

- Humber Pig

- Saracen APC

- Saxon APC

- Centurion AVRE (during Operation Motorman)

- Saladin armoured car

Aircraft

- Boeing Chinook

- Westland Sea King

- Aérospatiale Gazelle

- Westland Lynx

- Aérospatiale SA 330 Puma

- Westland Scout

- Bell H-13 Sioux

- Westland Wessex

- Britten-Norman Defender

- de Havilland Canada DHC-2 Beaver

Ships

- HMS Bildeston

- HMS Cygnet

- HMS Kingfisher

- HMS Fearless (during Operation Motorman)

- HMS Maidstone (as a prison ship)

Controversies

The British Army killed 305 people during Operation Banner, 156 (~51%) of whom were unarmed civilians.[8] Of these, 61 were children.[9] Elements of the Army also colluded with illegal loyalist paramilitaries responsible for numerous attacks on civilians (see below). The journalist Fintan O'Toole argues that "both militarily and ideologically, the Army was a player, not a referee".[10]

Relationship with the community

Many members of the Catholic community initially welcomed the Army's deployment. Catholic neighbourhoods had been attacked by Protestant loyalists and much of the Catholic community saw the police (RUC) as biased. However, relations soured between the Army and the Catholic community. The Army's actions in support of the police and the unionist government "gradually earned it a reputation of bias" in favour of the Protestant and unionist community.[11] In the Army's campaign against the IRA, Catholic areas were frequently subjected to house raids, checkpoints, patrols and curfews. There were frequent claims of soldiers physically and verbally abusing Catholics during these searches.[12][13][14] In some neighbourhoods, clashes between Catholic residents and British troops became a regular occurrence. In April 1970, Ian Freeland—the British Army's overall commander in Northern Ireland—announced that anyone throwing petrol bombs would be shot dead if they did not heed a warning from soldiers.[15]

The Falls Curfew, in July 1970, was a major blow to relations between the Army and Catholic community. A weapons search in the mainly Catholic Falls area of Belfast developed into a riot and then gun battles with the IRA. The Army then imposed a 36-hour curfew.[16][17][18][19] Any journalists inside the curfew zone were arrested by the Army.[20] It is claimed that, because the media were unable to watch them, the soldiers behaved "with reckless abandon". Hundreds of houses, pubs and businesses were searched for weapons and the area was saturated with CS gas.[20] The searches caused much destruction and there were scores of complaints of soldiers hitting, threatening, insulting and humiliating residents.[21] Four civilians were killed by the Army during the operation and another 60 suffered gunshot wounds.[22]

On 9 August 1971, internment (imprisonment without trial) was introduced in Northern Ireland. Soldiers launched dawn raids and interned almost 350 people suspected of IRA involvement. This sparked four days of violence in which 20 civilians were killed and thousands were forced to flee their homes. Seventeen civilians were killed by British soldiers – 11 of them in the Ballymurphy Massacre. No loyalists were included in the sweep and many of those arrested were ordinary Catholics with no IRA links. Many also reported that they and their families were assaulted, verbally abused and threatened by soldiers. The interrogation techniques used on the internees was described by the European Court of Human Rights as "inhuman and degrading",[23] and by the European Commission of Human Rights as "torture".[24] The operation led to mass protests and a sharp increase in violence over the following months. Internment lasted until December 1975 and during that time 1,981 people were interned.[25]

However, the real turning point in the relationship between the Army and the Catholic community was 30 January 1972: "Bloody Sunday". During an anti-internment march in Derry, 26 unarmed protesters and bystanders were shot by soldiers from the Parachute Regiment; fourteen died. Some were shot from behind or while trying to help the wounded. The Bloody Sunday Inquiry concluded in 2010 that the killings were "unjustified and unjustifiable".

On 9 July 1972, British troops in Portadown used CS gas and rubber bullets to clear nationalists who were blocking an Orange Order march through their area. The Army then let the Orangemen march into the Catholic area escorted by at least 50 masked and uniformed Ulster Defence Association (UDA) militants.[26][27][28] At the time, the UDA was a legal organization. That same day in Belfast, British snipers shot dead five Catholic civilians, including three children, in the Springhill Massacre. On the night of 3–4 February 1973, Army snipers shot dead four unarmed men (one of whom was an IRA member) in the Catholic New Lodge area of Belfast.[29]

In the early hours of 31 July 1972, the Army launched Operation Motorman to re-take Northern Ireland's "no-go areas". These were mostly Catholic neighbourhoods that had been barricaded by the residents to keep out the security forces and loyalists. During the operation, the Army shot four people in Derry, killing a 15-year-old Catholic civilian and an unarmed IRA member.

From 1971 to 1973, a secret Army unit known as the Military Reaction Force (MRF) carried out undercover operations in Belfast. It killed and wounded a number of unarmed Catholic civilians in drive-by shootings.[30] The Army initially claimed the civilians had been armed, but no evidence was found to support this. Former MRF members later admitted that the unit shot unarmed people without warning, both IRA members and civilians.[30] One member told the BBC "We were not there to act like an army unit, we were there to act like a terror group".[30] At first, many of the drive-by shootings were blamed on Protestant loyalists.[31] Republicans argue that the MRF sought to draw the IRA into a sectarian conflict and divert it from its campaign against the Army.[32] The MRF was succeeded by the SRU and, later, by the Force Research Unit (FRU).

On 12 and 17 May 1992, there were clashes between paratroopers and Catholic civilians in the town of Coalisland, triggered by a bomb attack which severed the legs of a paratrooper. The soldiers allegedly ransacked two pubs, damaged civilian cars and opened fire on a crowd. Three civilians were hospitalized with gunshot wounds. As a result, the Parachute Regiment was redeployed outside urban areas and the brigadier at 3 Infantry Brigade was relieved of his command.[33]

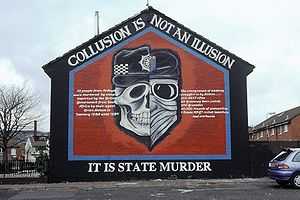

Collusion with loyalist paramilitaries

In their efforts to defeat the IRA, there were incidents of collusion between the British Army and loyalist paramilitaries throughout the conflict. This included soldiers taking part in loyalist attacks while off-duty, giving weapons or intelligence to loyalists, not taking action against them, and hindering police investigations. The British Army also had double agents and informers within loyalist groups who organized attacks on the orders of, or with the knowledge of, their Army handlers. The De Silva report found that, during the 1980s, 85% of the intelligence that loyalists used to target people came from the security forces.[34] A 2006 Irish Government report alleged that British soldiers also helped loyalists with attacks in the Republic of Ireland.[35]

Due to a number of factors, the locally-recruited Ulster Defence Regiment (UDR) was 97% Protestant from late 1972 onward.[36][37] Despite the vetting process, loyalist militants managed to enlist; mainly to obtain weapons, training and intelligence.[38] A 1973 British Government document (uncovered in 2004), "Subversion in the UDR", suggested that 5–15% of UDR soldiers then were members of loyalist paramilitaries.[39][40] The report said the UDR was the main source of weapons for those groups,[39] although by 1973 weapons losses had dropped by up to 75%, partly due to stricter controls.[39]

In 1977, the Army investigated two companies of 10 UDR based at Girdwood Barracks, Belfast. The investigation concluded that 70 soldiers had links to the UVF. Following this, two were dismissed on security grounds.[41] It found that thirty soldiers had fraudulently diverted up to £47,000 to the UVF, and that UVF members socialized with soldiers in their mess.[41] The investigation was halted after a senior officer claimed it was harming morale,[41] and details of it were uncovered in 2011.[41]

Initially, the Army allowed soldiers to join the UDA,[42] which remained a legal organization until 1992 despite its involvement in sectarian killings. In November 1972 the Army ordered that a soldier should be discharged if his sympathy for a paramilitary group affects his performance, loyalty or impartiality.[43] By the end of 1975, 171 soldiers with UDA links had been discharged.[44]

Eighteen UDR soldiers were convicted of murder and 11 for manslaughter.[45] By 1990, at least 197 soldiers had been convicted of terrorism and other serious crimes[46] including bombings, kidnappings and assaults.[47] This was a small fraction of the 40,000 who served with the regiment,[48] but the proportion was higher than for the regular British Army or RUC.[47]

During the 1970s, the Glenanne gang—a secret group consisting of loyalist militants, British soldiers and RUC officers—carried out a string of attacks against Catholics in an area of Northern Ireland known as the "murder triangle".[49][50][51] It also carried out some attacks in the Republic of Ireland. Lethal Allies: British Collusion in Ireland claims the group killed about 120 people, almost all uninvolved civilians.[52] The Cassel Report investigated 76 murders attributed to the group and found evidence that soldiers and policemen were involved in 74 of those.[53] One member, RUC officer John Weir, claimed his superiors knew of the collusion but allowed it to continue.[54] The Cassel Report also said that some senior officers knew of the crimes but did nothing to prevent, investigate or punish.[53] Attacks attributed to the group include the Dublin and Monaghan bombings (1974), the Miami Showband killings (1975) and the Reavey and O'Dowd killings (1976).[51][55]

The Stevens Inquiries concluded that the conflict had been intensified and prolonged by a core of army and police officers who helped loyalists to kill people, including civilians.[56][57] Members of the security forces tried to obstruct the Stevens investigation.[58][57] It revealed the existence of the Force Research Unit (FRU), a covert British Army intelligence unit that used double agents to infiltrate paramilitary groups.[59] FRU recruited Brian Nelson and helped him become the UDA's chief intelligence officer.[60] In 1988, weapons were shipped to loyalists from South Africa under Nelson's supervision.[60] Through Nelson, FRU helped the UDA target people for assassination. FRU commanders say their plan was to make the UDA "more professional" by helping it to target republican activists and prevent it killing uninvolved Catholic civilians.[59] The Stevens Inquiries found evidence only two lives were saved and that Nelson was responsible for at least 30 murders and many other attacks – many of the victims uninvolved civilians.[56] One of the most prominent victims was solicitor Pat Finucane. Although Nelson was imprisoned in 1992, FRU's intelligence continued to help the UDA and other loyalist groups.[61][62] From 1992 to 1994, loyalists were responsible for more deaths than republicans.[63]

Casualties

During the 38 year operation, 1,441 members of the British armed forces died in Operation Banner, including natural causes and suicide. [64]

- 692 soldiers in the regular British Army were killed as a result of paramilitary violence while another 689 died from other causes.

- 197 soldiers from the Ulster Defence Regiment were killed as a result of paramilitary violence while another 284 died from other causes.

- 7 soldiers from the Royal Irish Regiment were killed as a result of paramilitary violence while another 60 died from other causes.

- 9 soldiers from the Territorial Army were killed as a result of paramilitary violence while another 8 died from other causes.

- 2 members from other branches in the army were killed as a result of paramilitary violence.

- 21 Royal Marines were killed as a result of paramilitary violence while another 5 died from other causes.

- 8 Royal Navy servicemen were killed as a result of paramilitary violence while another 3 died from other causes.

- 4 Royal Air Force servicemen were killed as a result of paramilitary violence while another 22 died from other causes.

It was announced in July 2009 that their next of kin will be eligible to receive the Elizabeth Cross.[65]

According to the "Sutton Index of Deaths"[66] on CAIN, the British Army killed 305 people during Operation Banner.

- 156 (~51%) were civilians

- 127 (~41%) were members of republican paramilitaries, including:

- 110 members of the Provisional Irish Republican Army

- 11 members of the Official Irish Republican Army

- 5 members of the Irish National Liberation Army (INLA)

- 1 member of the Irish People's Liberation Organisation (IPLO)

- 13 (~4%) were members of loyalist paramilitaries, including:

- 7 members of the Ulster Defence Association (UDA)

- 6 members of the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF)

- 2 were Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) officers

Last years

The operation was gradually scaled down since 1998, after the Good Friday Agreement, when patrols were suspended and several military barracks closed or dismantled, even before the beginning of IRA's decommissioning.[67] The process of demilitarisation had already started in 1994, after the first IRA ceasefire. From the second IRA ceasefire in 1997 until the first act of decommission of weapons in 2001, almost 50 per cent of the army bases had been vacated or demolished along with surveillance sites and holding centers, while more than 100 cross-border roads were reopened.[68]

Eventually in August 2005, it was announced that in response to the Provisional IRA declaration that its campaign was over, and in accordance with the Good Friday Agreement provisions, Operation Banner would end by 1 August 2007.[69] This involved troops based in Northern Ireland reduced to 5,000, and only for training purposes. Security was entirely transferred to the police.[70] The Northern Ireland Resident battalions of the Royal Irish Regiment—which grew out of the Ulster Defence Regiment—were stood down on 1 September 2006. The operation officially ended at midnight on 31 July 2007, making it the longest continuous deployment in the British Army's history, lasting over 38 years.[4] In the words of BBC correspondent Kevin Connolly , the British Army in Northern Ireland "melted away, rather than marched away".[71] While the withdrawal of troops was welcomed by the nationalist parties Social Democratic and Labour Party and Sinn Féin, the unionist Democratic Unionist Party and Ulster Unionist Party opposed to the decision, which they regarded as 'premature'. The main reasons behind their resistance were the continuing activity of republican dissident groups, the loss of security-related jobs for the protestant community and the perception of the British Army presence as an affirmation of the political union with Great Britain.[72]

Adam Ingram, the Minister of State for the Armed Forces, has stated that assuming the maintenance of an enabling environment, British Army support to the PSNI after 31 July 2007 was reduced to a residual level, known as Operation Helvetic, providing specialised ordnance disposal and support to the PSNI in circumstances of extreme public disorder as described in Patten recommendations 59 and 66, should this be needed,[73][74] thus ending the British Army's emergency operation in Northern Ireland.

Analysis of the operation

In July 2007, under the Freedom of Information Act 2000 the Ministry of Defence published Operation Banner: An analysis of military operations in Northern Ireland, which reflected on the Army's role in the conflict and the strategic and operational lessons drawn from their involvement.[2][4] The paper divides the IRA activity and tactics in two main periods: The "insurgency" phase (1971–1972), and the "terrorist" phase (1972–1997).[75] The British Army claims to have curbed the IRA insurgency by 1972, after Operation Motorman. The IRA then reemerged as a cell-structured organisation.[75] The report also asserts that the government efforts by the 1980s were aimed to destroy the IRA, rather than negotiate a political solution.[76] One of the findings of the document is the failure of the British Army to tackle the IRA at strategic level and the lack of a single campaign authority and plan.[77] The paper stops short of claiming that "Northern Ireland has achieved a state of lasting peace" and acknowledges that as late as 2006, there were still "areas of Northern Ireland out of bounds to soldiers."[78]

The report analyses Israeli military theorist Martin van Creveld's comments on the outcome of the operation:

| “ | Martin van Creveld has said that the British Army is unique in Northern Ireland in its success against an irregular force. It should be recognised that the Army did not 'win' in any recognisable way; rather it achieved its desired end-state, which allowed a political process to be established without unacceptable levels of intimidation. Security force operations suppressed the level of violence to a level which the population could live with, and with which the RUC and later the PSNI could cope. The violence was reduced to an extent which made it clear to the PIRA that they would not win through violence. This is a major achievement, and one with which the security forces from all three Services, with the Army in the lead, should be entirely satisfied. It took a long time but, as van Crefeld [sic] said, that success is unique.[4] | ” |

The US military have sought to incorporate lessons from Operation Banner in their field manual.[79]

References

- ↑ Taylor, Peter,Behind the mask: The IRA and Sinn Féin, Chapter 21: Stalemate, pp. 246–261.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 "Army paper says IRA not defeated". BBC News. 2007-07-06. Retrieved 2008-03-21.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Wilkinson, Paul (2006). Terrorism versus democracy: the liberal state response. Taylor & Francis, p. 68. ISBN 0-415-38477-X

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 "Operation Banner: An analysis of military operations in Northern Ireland" (PDF). Ministry of Defence. 2006. Retrieved 2009-07-31.

- ↑ "Operation Banner: An analysis of military operations in Northern Ireland" (PDF). Ministry of Defence. 2006. Retrieved 2009-07-31. Chapter 6, pp. 1–2

- ↑ Ripley, Tim and Chappel, Mike (1993). Security forces in Northern Ireland (1969–92). Osprey, pp. 19–21. ISBN 1-85532-278-1

- ↑ More Troops Arrive in Northern Ireland Associated Press, 10 July 1997

- ↑ Sutton Index of Deaths. Conflict Archive on the Internet (CAIN).

- ↑ Smyth, Marie. Deaths of children and young people in the Troubles. Conflict Archive on the Internet (CAIN).

- ↑ Fintan O'Toole (2007-07-31). "The blunt instrument of war". Irish Times. Retrieved 2008-03-21.

- ↑ Weitzer, Ronald John. Transforming Settler States: Communal Conflict and Internal Security in Northern Ireland and Zimbabwe. University of California Press, 1990. pp. 120, 205

- ↑ Brett Bowden & Michael T. Davis. Terror: From Tyrannicide to Terrorism. University of Queensland Press, 2008. p. 234

- ↑ Dillon, Martin. The Dirty War. Random House, 1991. p. 94

- ↑ Northern Ireland: Continued abuses by all sides. Human Rights Watch, March 1994.

- ↑ Chronology of the Conflict - 1970. Conflict Archive on the Internet (CAIN).

- ↑ Northern Ireland Since c.1960 by Barry Doherty (ISBN 978-0435327286), page 11

- ↑ Freedom or Security: The Consequences for Democracies Using Emergency Powers to Fight Terrorism by Michael Freeman (ISBN 978-0275979133), page 53

- ↑ Mick Fealty (2007-07-31). "About turn". Guardian Comment is Free. Retrieved 2008-03-21.

- ↑ Kevin Connolly (2007-07-31). "No fanfare for Operation Banner". BBC News. Retrieved 2008-03-21.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Dillon, Martin (1999). The Dirty War: Covert strategies and tactics used in political conflicts. Taylor & Francis. pp. 212–3.

- ↑ Ó Fearghail, Seán Óg (1970). Law (?) and Orders: The Belfast 'Curfew' of 3–5 July 1970. Dundalgan Press. pp. 35–36. Retrieved 5 November 2013.

- ↑ Dillon, Martin (1999). The Dirty War: Covert strategies and tactics used in political conflicts. Taylor & Francis. pp. 212–213. ISBN 041592281X.

- ↑ IRELAND v. THE UNITED KINGDOM - 5310/71 (1978) ECHR 1 (18 January 1978)

- ↑ Weissbrodt, David. Materials on torture and other ill-treatment: 3. European Court of Human Rights (doc) html: Ireland v. United Kingdom, 1976 Y.B. Eur. Conv. on Hum. Rts. 512, 748, 788-94 (Eur. Comm’n of Hum. Rts.)

- ↑ Joint Committee on Human Rights, Parliament of the United Kingdom (2005). Counter-Terrorism Policy And Human Rights: Terrorism Bill and related matters: Oral and Written Evidence. Counter-Terrorism Policy And Human Rights: Terrorism Bill and related matters 2. The Stationery Office. p. 110.

- ↑ Kaufmann, Eric P. The Orange Order: a contemporary Northern Irish history. Oxford University Press, 2007. p.154.

- ↑ Bryan, Dominic. Orange parades: the politics of ritual, tradition, and control. Pluto Press, 2000. p. 92.

- ↑ Belfast Telegraph, 12 July 1972, p. 4.

- ↑ "Unofficial inquiry will examine north Belfast's 'Bloody Sunday'". Irish News, 8 November 2002.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 30.2 "Undercover soldiers 'killed unarmed civilians in Belfast'". BBC News. 21 November 2013. Retrieved 22 November 2013.

- ↑ Ed Moloney (November 2003). A secret history of the IRA. W. W. Norton & Company. pp. 119–. ISBN 978-0-393-32502-7. Retrieved 7 February 2011.

- ↑ Dillon, The Dirty War, pp. 55–56

- ↑ Fortnight issues 302-12, Fortnight Publications, 1992, p. 6

- ↑ "Pat Finucane murder: 'Shocking state collusion', says PM". BBC News, 12 December 2012. Retrieved 13 December 2012.

- ↑ "British 'colluded with loyalists'". BBC News. 29 November 2006.

- ↑ Thomas G. Mitchell, Native Vs. Settler: Ethnic Conflict in Israel/Palestine, Northern Ireland, p. 55

- ↑ Brett Bowden, Michael T. Davis, eds, Terror: From Tyrannicide to Terrorism, p. 234

- ↑ "CAIN: Public Records: Subversion in the UDR". Cain.ulst.ac.uk. Retrieved 2013-07-17.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 39.2 "Subversion in the UDR". Conflict Archive on the Internet (CAIN)

- ↑ "Collusion - Subversion in the UDR". Irish News, 3 May 2006.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 41.2 41.3 "British army 'covered up' UDR units links to UVF". The Detail, 31 July 2011.

- ↑ Wood, Ian S. Crimes of Loyalty: A History of the UDA. Edinburgh University Press, 2006. pp.107-8

- ↑ CAIN: New Year Releases 2003 - Public Records of 1972

- ↑ Potter, John Furniss. A Testimony to Courage – the Regimental History of the Ulster Defence Regiment 1969–1992. Pen & Sword Books, 2001. p.376

- ↑ Ryder p150

- ↑ Eldridge, John. Getting the Message: News, Truth, and Power. Routledge, 2003. p.91

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 Weitzer 1990, p. 208

- ↑ Potter p383

- ↑ Tiernan, Joe (2000). The Dublin Bombings and the Murder Triangle. Ireland: Mercier Press

- ↑ The Cassel Report (2006), pp. 8, 14, 21, 25, 51, 56, 58–65.

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 [http://www.patfinucanecentre.org/sarmagh/sarmagh.html "Collusion in the South Armagh/Mid Ulster Area in the mid-1970s". Pat Finucane Centre. Retrieved 2 January 2011.

- ↑ Lethal Allies: British Collusion in Ireland - Conclusions. Pat Finucane Centre.

- ↑ 53.0 53.1 The Cassel Report (2006), p.4

- ↑ The Cassel Report (2006), p.63

- ↑ The Cassel Report (2006), p.8

- ↑ 56.0 56.1 "Scandal of Ulster’s secret war". The Guardian. 17 April 2003. Retrieved 27 September 2013.

- ↑ 57.0 57.1 "Security forces aided loyalist murders". BBC News. 17 April 2003. Retrieved 27 September 2013.

- ↑ Stevens Enquiry 3: Overview & Recommendations. 17 April 2003. Retrieved 27 September 2013.

- ↑ 59.0 59.1 "Stevens Inquiry: Key people". BBC News. 17 April 2003. Retrieved 27 September 2013.

- ↑ 60.0 60.1 "Obituary: Brian Nelson". The Guardian. 17 April 2003. Retrieved 27 September 2013.

- ↑ “Deadly Intelligence: State Involvement in Loyalist Murder in Northern Ireland – Summary”. British Irish Rights Watch, February 1999.

- ↑ Human Rights in Northern Ireland: Hearing before the Committee on International Relations of the United States House of Representatives, 24 June 1997. US Government Printing Office, 1997.

- ↑ Clayton, Pamela (1996). Enemies and Passing Friends: Settler ideologies in twentieth-century Ulster. Pluto Press. p. 156.

More recently, the resurgence in loyalist violence that led to their carrying out more killings than republicans from the beginning of 1992 until their ceasefire (a fact widely reported in Northern Ireland) was still described as following 'the IRA's well-tested tactic of trying to usurp the political process by violence'...

- ↑ "Operation Banner Deaths". https://www.whatdotheyknow.com/request/143521/response/357035/attach/html/3/20130129%20FOI%20Smyth%2002%2001%202013%20160507%20018%20U.doc.html''.

- ↑ MOD press release

- ↑ CAIN – Sutton Index of Deaths

- ↑ O'Brien, Brendan (1999). The Long War: The IRA and Sinn Féin, Syracuse University Press, p 393. ISBN 0-8156-0597-8

- ↑ Albert, Cornelia (2009). The Peacebuilding Elements of the Belfast Agreement and the Transformation of the Northern Ireland Conflict. Peter Lang, p. 234. ISBN 3-631-58591-8

- ↑ Brian Rowan (2005-08-02). "Military move heralds end of era". BBC News. Retrieved 2008-03-21.

- ↑ Army ending its operation in NI BBC News, 31 July 2007

- ↑ No fanfare for Operation Banner BBC News, 31 July 2007

- ↑ Albert, p. 236

- ↑ "House of Commons Hansard Written Answers for 13 Sep 2006 (pt 2356)". Houses of Parliament. 2006-09-13. Retrieved 2008-03-21.

- ↑ Ministry of Defence

- ↑ 75.0 75.1 Operation Banner, Chapter I, page 3

- ↑ Operation Banner, Chapter II, page 15: "The British Government’s main military objective in the 1980s was the destruction of PIRA, rather than resolving the conflict."

- ↑ Operation Banner, Chapter VIII, p. 4

- ↑ Operation Banner, Chapter II, page 16

- ↑ Richard Norton Taylor and Owen Bowcott (2007-07-31). "Analysis: Army learned insurgency lessons from Northern Ireland". The Guardian. Retrieved 2008-03-21.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Northern Ireland Troubles. |

- BBC News story about the ending of Operation Banner

- BBC News, Operation Banner pictures

- "Operation Banner: An analysis of military operations in Northern Ireland" (PDF). Ministry of Defence. 2006. Retrieved 2009-07-31.

- Site with Roll of Honour, news and forums on Operation Banner

- Reeling in the Years – 1971: Raidió Teilifís Éireann

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||