Open plan

Open plan is the generic term used in architectural and interior design for any floor plan which makes use of large, open spaces and minimizes the use of small, enclosed rooms such as private offices. The term can also refer to landscaping of housing estates, business parks, etc., in which there are no defined property boundaries, such as hedges, fences or walls. In residential design, open plan or open concept (the term used mainly in Canada[1]) describes the elimination of barriers such as walls and doors that traditionally separated distinct functional areas, such as kitchen, living room, and dining room.

Homes

In the 1880s, small public rooms of the home with specific functions began to be replaced by larger rooms that would fulfill multiple uses; with the kitchen, bedrooms and bathrooms still being enclosed private spaces.[2] Larger rooms were made possible by advances in centralized heating that allowed larger spaces to be kept at comfortable temperatures.[2]

Frank Lloyd Wright was one of the early advocates for open plan design in houses,[3] expanding on the ideas of Charles and Henry Greene and shingle style architecture.[4] Wright's designs were based on a centralized kitchen which opened to other public spaces of the home where the housewife would be "more hostess 'officio', operating in gracious relation to her home, instead of being a kitchen mechanic behind closed doors."[5]

Office spaces

Development of open plan workspace types

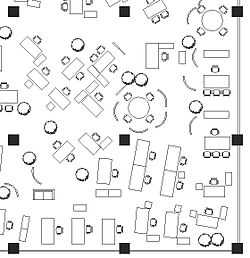

Prior to the 1950s, open plan offices mostly consisted of large regular rows of desks or benches where clerks, typists, or technicians performed repetitive tasks.[6] Such designs were rooted in the work of industrial engineers or efficiency experts such as Frederick Winslow Taylor and Henry Ford. In the 1950s, a German team named Quickborner developed office landscape which used conventional furniture, curved screens, large potted plants, and organic geometry to create work groups on large, open floors. Office landscape was quickly supplanted by office furniture companies which developed cubicles based on panel-hung or systems furniture. Many terms (mostly derisive) have been used over time for offices using the old-style, large arrays of open cubicles.

An increase in knowledge work and the emergence of mobile technology during the late 20th Century led to an evolution in open plan offices.[7][8] Many companies are experimenting with designs which provide a mix of cubicles, open workstations, private offices, and group workstations. In some cases, these are not assigned to one particular individual, but are available to any employee of the company on either a reservable or "drop-in" (first come, first served) basis. Terms for this strategy include office hotelling and alternative officing.[9]

Michael Bloomberg used a team-oriented bullpen style, where employees can see and hear each other freely, but desks are grouped into teams at his media company Bloomberg L.P. and for his staff while Mayor of New York City.[10]

Advantages and disadvantages

A systematic survey of research upon the effects of open plan offices found frequent negative effects in some traditional workplaces: high levels of noise, stress, conflict, high blood pressure and a high staff turnover.[11] The noise level greatly reduces the productivity, which drops to one third relative to what it would be in quiet rooms.[12] Open plan offices have frequently been found to reduce the confidential or private conversations employee engage in, reduce job satisfaction, concentration and performance, whilst increasing auditory and visual distractions.[8][13]

Neither open nor closed plan offices are perfect for any one situation or individual. The right balance is required. Any office design is likely to involve trade-offs for the workers, with some positives and negatives.[13]

Architect Frank Duffy developed a taxonomy to classify the form of office space that would suit different types of workers.[6] How much interaction individuals require, the work design (i.e., the amount of job autonomy), together with the information technology available, predict the office design that may best suit the worker.

See also

References

- ↑ Definition of open-concept at Dictionary.com

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Ward, Peter (2011-01-01). A History of Domestic Space: Privacy and the Canadian Home. UBC Press. pp. 37–. ISBN 9780774841825. Retrieved 1 June 2014.

- ↑ Schwartz, Tony; Gomes, Jean; McCarthy, Catherine (2011-02-01). Be Excellent at Anything: The Four Keys To Transforming the Way We Work and. Simon and Schuster. pp. 224–. ISBN 9781451639452. Retrieved 1 June 2014.

- ↑ Elliott, Lynn (May–June 2002). "Breaking Down Walls". Old-House Journal (Active Interest Media, Inc.): 50–53. Retrieved 1 June 2014.

- ↑ Schoenauer, Norbert (2003-06-24). 6,000 Years of Housing. W.W. Norton. pp. 384–. ISBN 9780393731200. Retrieved 1 June 2014.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Duffy, F. (1997). The new office. London Conran Octopus

- ↑ Gillen, N. M. (2006). The Future Workplace, Opportunities, Realities and Myths: A Practical Approach to Creating Meaningful Environments. In J. Worthington (Ed.), Reinventing the Workplace (2nd ed., pp. 61–78). Oxford: Architectural Press.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Davis, M. C., Leach, D. J., & Clegg, C. W. (2011). The Physical Environment of the Office: Contemporary and Emerging Issues. In G. P. Hodgkinson & J. K. Ford (Eds.), International Review of Industrial and Organizational Psychology (Vol. 26, pp. 193–235). Chichester, UK: Wiley. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/9781119992592.ch6

- ↑ Cornell study

- ↑ Nagourney, Adam. "Bloomberg Vows to Work at Center of Things", New York Times

- ↑ Dr Vinesh Oommen (13 Jan 2009), "Why your office could be making you sick", Asia-Pacific Journal of Health Management

- ↑ Julian Treasure TED talk: The 4 ways sound affects us

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Elsbach, K. D., & Pratt, M. G. (2007). Chapter 4: The Physical Environment in Organizations. The Academy of Management Annals, 1(1), 181–224.