Onitsha

| Onitsha Ọ̀nị̀chà Mmílí | |

|---|---|

| City | |

|

Top: Onitsha landscape. Middle: River Niger Bridge heading from Onitsha. Bottom left: The Onitsha Niger River Port. Bottom right: Welcome signboard while entering Onitsha, Anambra State. | |

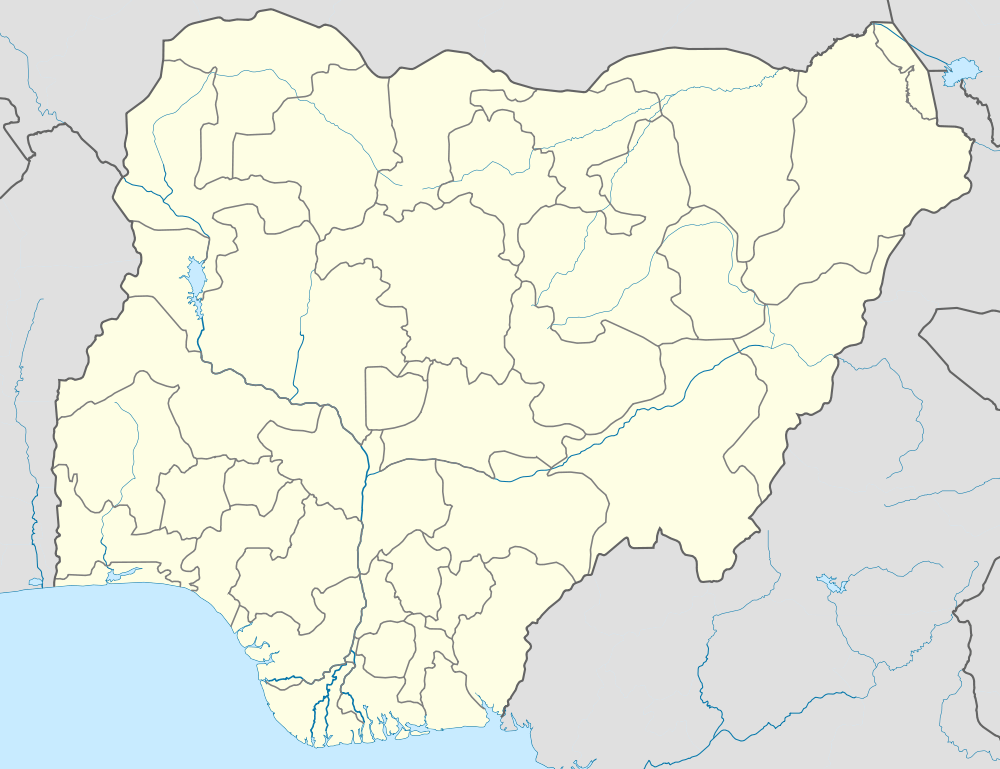

Onitsha Onitsha in Nigeria | |

| Coordinates: 6°10′N 6°47′E / 6.167°N 6.783°E | |

| Country |

|

| State | Anambra State |

| LGA | Onitsha North, Onitsha South |

| Founded | 1550 |

| Government | |

| • Obi | Igwe Nnayelugo Alfred Nnaemeka Achebe |

| Area[1] | |

| • City | 13.97 sq mi (36.19 km2) |

| • Land | 13.95 sq mi (36.12 km2) |

| • Water | 0.026 sq mi (0.067 km2) |

| • Urban | 9.83 sq mi (25.45 km2) |

| • Metro | 13.97 sq mi (36.19 km2) |

| Population (2002)[1][2] | |

| • City | 511,000 |

| • Density | 113,900/sq mi (43,978/km2) |

| • Metro | 1,003,000(Unofficial) |

| • Ethnicity | Igbo 90%>, Others |

| • Demonym |

Onye Onicha (singular) Ndi Onicha (plural) (Igbo) |

| Time zone | WAT (UTC+1) |

| Postcode | 430...[3] |

| Area code(s) | 046 |

Onitsha (Igbo: Ọ̀nị̀chà Mmílí[4] or just Ọ̀nị̀chà)[5] is a city, a commercial, educational, and religious centre and river port on the eastern bank of the Niger river in Anambra State, southeastern Nigeria.

In the early 1960s, before the Nigerian Civil War (see also Biafra), the population was officially recorded as 76,000, and the town was distinctive in a number of dimensions; the great Nigerian writer Chinua Achebe (born and raised in the contiguous town of Ogidi) characterized it as harboring an "esoteric region from which creativity sallies forth at will to manifest itself," "a zone of occult instability" (see "Onitsha Matters" ). Though it experienced great suffering during and after the civil war, by virtue of its still-strategic geographic position Onitsha has continued to develop, and by 2001 had an estimated population of 511,000 with a metropolitan population of 1,003,000.[2] The indigenous people of Onitsha are Igbo and speak the Igbo language.

History

Most theories on the word 'Onicha' point to the meanings "despiser" or "arrogant"; apparently the people of Onitsha were prone to "look down" upon the people of the towns adjacent to them.[6] 'Onicha' may be a contraction of either 'Ọnịsịlị-ncha', meaning 'too headstrong [to be disciplined]'; Ọnyịsịlị-ncha, 'too headstrong [for everyone]'; or 'Ani-Ocha', 'the fair or white land'. Some claim that 'Onicha' is a contraction of Igbo and Edo words, and perhaps from the word 'Orisha'. Therefore, as a matter of verifiable fact, there are as well other communities east of the Niger River kwown as Onicha with differing appendages. The communities are as follows: Onicha Uburu (Ebonyi state), Onicha Uboma (Imo state), Onicha Agu (Enugu state), Onicha Nwenkwo (Imo state), Onicha Ngwa (Abia state), Onicha Amagunze(Enugu state) etc.[7]

Onitsha Mmili was known as Ado N'Idu by migrants who departed from the vicinity of the Kingdom of Benin near the far western portion of Igboland (near what is now Agbor), after a violent dispute with the Oba of Benin that can be tentatively dated to the early 1500s.[8] Traveling eastward through what is now Western Igboland (and various towns also called "Onitsha", for example Onicha-Ugbo, "farmland-Onitsha". Onitsha was founded by one of the sons of Chima, the founder of Issele-Uku kingdom. Chima, a prince of the ancient Benin kingdom emigrated, settled and founded now known as Issele-Uku in Aniocha North Local Government Area. The eldest son of Chima eventually emigrated across the Niger River to establish the Onitsha community. After their arrival on the east bank (Onicha-mmili, "Onitsha-on-water", see above), the community gradually became a unitary kingdom, evolving from a loosely organized group of "royal" and "non-royal" villages into a more centralized entity.[9] Eze Aroli, was apparently the first genuinely powerful Obi of Onitsha, the ruler of the city.[10]

In 1857 British palm oil traders established a permanent station in the city, Christian missionaries joining them headed by the liberated African bishop Samuel Ajayi Crowther (a Yoruba recaptive) and Reverend John Taylor (an Igbo Recaptive).[11] In 1900 Onitsha became part of a British protectorate.[12]{ The British colonial government and Christian missionaries penetrated most of Igboland to set up their administration, schools and churches through the river port at Onitsha.

Modern history

Onitsha became an important trading port for the Royal Niger Company in the mid-1850s following the abolition of slavery and with the development of the steam engine when Europeans were able to move into the hinterland. Trade in palm kernels and palm oil which was going on on the coast of Bight of Biafra since 12th century was now moved upwards and other cash crops also boomed around this river port in the 19th century. Immigrants from the hinterland of Igboland were drawn to the emerging boom town as did the British traders who settled there in Onitsha, and coordinated the palm oil and cash crops trade. In 1965, the Niger River Bridge was built across the Niger River to replace the ferry crossing.

Demography

Today, Onitsha is a modern day urban society in Anambra State. The people speak the Igbo and English languages.

There is a Catholic cathedral and an Anglican cathedral in Onitsha that are the headquarters of their satellite churches in and outside Onitsha. Other minor churches have their headquarters such as Grace of God Mission International, Christ Holy Church, Mountain of Fire and Miracles and many other church organizations and socio-cultural groups.

A federal government college is in the town. There is an army barrack and a school of metallurgy. It is the home of the biggest market in Africa, the Onitsha Main Market. The Onitsha people were the first to embrace western education, producing notable people like Dr. Nnamdi Azikiwe, Owele of Onicha, Zik of Africa, and the first president of the post independent Nigeria, Prof. Chike Obi, Justice Phillip Ebosie, and Philip Emeagwali.

In recent times the Onitsha people have been involved in disputes over land ownership in the surrounding area with the people of Obosi and Nkwellezunka.[13][14][15][16]

Economy

The state of Lagos and various northern towns are partially fed by supplies from Onitsha. Trade soared between the east and west of Nigeria because of Onitsha market. This made Onitsha the strategic gateway for trade between the former eastern and western regions. The Nigerian-Biafran war brought widespread devastation to the city; at its end came the subsequent oil boom years bringing a huge influx of immigrants into the city. The war-damaged facilities, still under repair, could not cope with the pace of the rural-urban exodus into the city. Slums consequently began to emerge from the hasty haphazard building construction to accommodate the huge influx.

The Onitsha Brewery started production in August 2012. In January it was announced that upgrades to the value of $110 million would triple the output of beer and malt drinks.[17]

Geography

Onitsha lies at a major east-west crossing point of the Niger River, and occupies the northernmost point of the river regularly navigable by large vessels. These factors have historically made Onitsha a major center for trade between the coastal regions and the north, as well as between eastern and western Nigeria. Onitsha possesses one of the very few road bridge crossings of the mile-wide Niger River[18][19] and plans are in place to add a second bridge near it. Today, Onitsha is a textbook example of the perils of urbanization without planning or public services.

Religion and politics

The Cathedral Basilica of the Most Holy Trinity is the seat of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Onitsha. The Church Of Nigeria Anglican Communion Anglicanchurch has All Saints'cathedral the Headquarters of Diocese on the Niger with Rt. Rev Owen Chiedozie Nwokolo the Bishop On the Niger in the city. The Anglican was the first missionary in Onitsha in 1857. Later came the Catholics in 1884. It is the residence of the traditional ruler of Onitsha, the Obi of Onitsha. There is also a teacher training college for women and a famous leper colony. Despite being one of the biggest commercial cities of west Africa, Onitsha remains congested from the over-concentration of all her huge markets within the old city center and minimal expansion of the colonial roads infrastructure.

In February 2006, armed militants killed at least 24 ethnic Hausa Fulani (Muslims) and burned a few Muslim sites including two mosques.[20][21][22] The riots were in response to riots by Muslims in the city of Maiduguri days earlier, where at least 18 Christians were killed, sparked by the cartoon controversy in Denmark.

Sister cities

Compton, California, United States (2010)[23]

Compton, California, United States (2010)[23]

Notable residents

- Ebele Okoye, painter and animator

See also

- Onitsha Market Literature - literature sold at the main market in the 1950s and 60s.

- - "Onitsha Matters", a website presenting many facets of Onitsha history in its geographic and cultural context, including many topics and numerous photographic images.

- The King in Every Man: Evolutionary Trends in Onitsha Ibo Society and Culture")] an (1972) Anthropological study of precolonial Onitsha in its regional contexts [(Richard Henderson) Yale University Press] (Reprinted in 1996 as ISBN 0-97404-400-8)

- Onitsha is the title of a novel by French author J. M. G. Le Clézio

- Ryszard Kapuscinski writes of "The Hole of Onitsha" in his book The Shadow of the Sun.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 UN Habitat (2009). "Structure Plan for Onitsha and Satellite Towns". UN-HABITAT. ISBN 978-92-1-132117-3.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Minahan, James (2002). Encyclopedia of the Stateless Nations: S-Z. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 762. ISBN 0-313-32384-4.

- ↑ "Nipost Postcode Map". Nigerian Postal Service. Retrieved 2010-05-08.

- ↑ Okanga, Eloka Chijioke Paul Nwolisa (2003). Njepu amaka--migration is rewarding: a sociocultural anthropological study of global economic migration. Peter Lang. p. 63. ISBN 0-8204-6090-7.

- ↑ Egbokhare, Francis O.; Oyetade, S. Oluwole (2002). Harmonization and standardization of Nigerian languages. CASAS. p. 106. ISBN 1-919799-70-2.

- ↑ Bosah, Nnayelugo S. I. (1979). Groundwork of the history and culture of Onitsha. Time Press Ltd. p. 4.

- ↑ Hahn-Waanders, Hanny (1990). Eze institution in Igboland: a study of an Igbo political system in social change. Asele Institute. p. 94. ISBN 978-2442-24-0.

- ↑ Henderson, Richardl N (1972). The King in Every Man: Evolutionary Trends in Onitsha Ibo Society and Culture. Yale University Press. pp. 42–46. ISBN 0-300-01292-6.

- ↑ Henderson, Richardl N (1972). The King in Every Man: Evolutionary Trends in Onitsha Ibo Society and Culture. Yale University Press. pp. 29–102. ISBN 0-300-01292-6.

- ↑ Nigerian traditional poilities

- ↑ Taylor, Crowther & (2010) [1859]. The Gospel on the Banks of the Niger: Journals and Notices of the Native Missionaries Accompanying the Niger Expedition of 1857-1859. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-108-01184-6..

- ↑ Anene, J.C. (1966). Southern Nigeria in Transition 1885-1906. Cambridge University Press. pp. 212–213.

- ↑ Vincent Ujumadu (June 17, 2013). "17 injured, bus burnt as Onitsha, Obosi youths clash over land". Vanguard. Retrieved September 2, 2014.

- ↑ Nigeria: "Nkwelle-Ezunaka Battles Onitsha Over Land". Nkwelle Ezunaka Union USA. Retrieved September 2, 2014.

- ↑ edrixpure (July 1, 2013). Divided Over Land Ownership Tussle. Nigeria Best Forum. Retrieved September 2, 2014.

- ↑ Abagworo (February 4, 2011). Crisis Brews In Onitsha, Nkwellezunka. ₦airaland Forum. Retrieved September 2, 2014.

- ↑ "SAB Miller investing $110 m to triple Onitsha brewery capacity". Retrieved 28 February 2014.

- ↑ "The second Niger Bridge". The Daily Sun. 2007-02-20. Retrieved 2007-04-06.

- ↑ "Britannica". Retrieved 2008-10-02.

- ↑ "Scores killed in Nigeria riots". "Al Jazeera". 2006-02-23.

- ↑ "Toll rises in Nigeria sectarian riots". "Al Jazeera". 2006-02-24.

- ↑ Timberg, Craig (2006-02-24). "Nigerian Christians Burn Corpses". "The Washington Post". pp. A10. Retrieved 2007-04-06.

- ↑ "Sister Cities of Compton". comptonsistercities.org. Retrieved 2013-07-02.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||