Olyftack

| De Olyftack | |

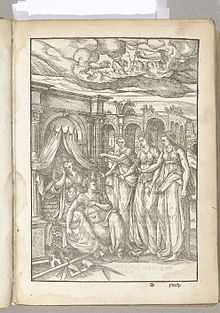

An engraved representation of the blazon of the Olyftack at the 1561 rhetoric competition in Antwerp | |

| Motto | Ecce gratia |

|---|---|

| Formation | 1510 |

| Extinction | 1762 |

| Type | Chamber of rhetoric |

| Location | |

Region | Duchy of Brabant |

| Methods | amateur and semi-professional dramatic and recitative performance |

Membership (1615) | 76 fee-paying members; 16 actors |

Official language | Dutch |

Honorary president | Hooftman |

Chairman | Prince |

Executive officer | Opperdeken |

Executive assistant | Mededeken |

Key people |

Accoustrementmeester (properties master) Breuckmeesters (responsible for collecting membership fees) Busmeester (responsible for collecting alms for sick or "decayed" members) Princen van personagiën (casting directors) |

Staff | personagiën, confreers |

Volunteers | liefhebbers |

The Olyftack (Olive Branch), or in full Gulde van den Heyligen Geest die men noempt den Olyftack (Confraternity of the Holy Spirit called the Olive Branch) was a chamber of rhetoric that dates back to the early 16th century in Antwerp, when it was a social drama society drawing its membership primarily from merchants and tradesmen.[1] In 1660 it merged with its former rival the Violieren (which was more closely associated with artists and intellectuals), and in 1762 the society was dissolved altogether.

History

The chamber took part in the landjuweel (a rhetoric competition for the whole Duchy of Brabant) at Mechelen in 1515, at Diest in 1521, at Brussels in 1532, at Mechelen in 1535, at Diest in 1541, and the final such competition, at Antwerp in 1561.

The chamber also provided public entertainment at such events as the triumphal entry into Antwerp of Alexander Farnese, Duke of Parma. During the 1590s there were no regular public performances, and for much of the decade meetings were prohibited by decree, but after 1600 members and sympathisers of the guild again began to meet weekly for dramatic and rhetorical exercises. During the Twelve Years' Truce, representatives of the Olyftack attended a rhetoric competition hosted in Amsterdam on 7 July 1613 by the Amsterdam chamber Wit Lavendel (White lavender), and another hosted in Haarlem by the Wyngaertranken (the Vines) on 18 August 1613. The organisation was overhauled in 1615. In 1618 the Olyftack hosted a blazoenfeest in Antwerp: a rhetoric competition in which chambers entered "blazons", or painted and decorated verse rebuses carried in procession, with prizes for best rhyme, best delivery, best painting, best decoration, best procession, and so on. In 1619 the chamber was deeply in debt, having overspent on banquets and performances.[1]

They nevertheless took part in the blazoenfeest hosted by the Peoene (Peony) in Mechelen on 3 May 1620. Members of the Olyftack carried off second prize for best rhyming rebus, third prize for best painted rebus, third prize for most triumphant decoration, first prize for best composed verse, third prize for strongest line, first and second place for best recitation, first prize for best song, and second prize for most pieces entered by a single chamber.[2]

For the play put on for the chamber's feestdag in 1621, 400 programmes were printed. The chamber was prominent in the civic celebrations of the Habsburg victories in the Battle of White Mountain (1620), the Battle of Stadtlohn (1623) and the Siege of Breda (1625), and for the ceremonies of public mourning for the death of Albert VII, Archduke of Austria in 1621.[1]

The chamber seems to have gone into decline after 1629, and in 1646 their costumes were bought up by the rival Violieren.[3] It may have continued to exist as a dining club with a literary angle, rather than a drama society.[1] In 1660, when the Violieren and the remnants of the Olyftack merged, the new chamber took the name Olyftack, or den herstelden Olyf-tack (the repaired Olive Branch).

Organisation

The leading officers of the chamber were the hooftman, prince, senior dean (opperdeken) and assistant dean (mededeken). The hooftman (headman) was an honorary president, a non-participating patron, who audited the chamber's accounts and mediated disputes between members. He was elected for a term of three years. The prince, who chaired the actual running of the organisation, was also elected for three years. The dean and assistant dean, who did the actual work of administering the guild, were elected for terms of two years.[1]

Other officers were the casting directors (princen van personagiën), the properties master (accoustrementmeester), the breuckmeesters who collected members' fees, and the busmeesters who organised collections for sick or "decayed" members. The social functions of the chamber, like those of a guild, included attending the funerals of deceased members, providing wedding presents to members who married, and providing support for sick or impoverished members. The guild employed a facteur to carry messages, collect or deliver prizes, and convey congratulations, and a knaap to do odd jobs, notify members of funerals or of extraordinary meetings, tidy the hall, and act as doorman during performances.[1]

By the 17th-century, the chamber enjoyed the services of semi-professional actors (personagiën) who did not pay membership fees, were provided with free food and drink at rehearsals and performances, received 6 florins for attending the funerals of guild members, and were exempt from militia duty. They worked under the direction of the princen van personagiën. The fee-paying members, or confreers, enjoyed not only freedom from militia duty but the full range of social provision that the guild provided. It was also possible to pay entrance fees, rather than membership fees, as a "sympathiser" (or liefhebber), without enjoying the full rights of guild membership.[1]

Records

The accounts for 1615–1629 have been published:

- Emiel Dilis, (ed.), De rekeningen der rederijkkamer De Olijftak over de jaren 1615 tot 1629 (Antwerp and The Hague, 1910).

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 A. A. Keersmaekers, Geschiedenis van de Antwerpse Rederijkerskamers in de jaren 1585–1635 (Aalst, 1952)

- ↑ Jan Thieullier, ed., De schadt-kiste der philosophen ende poeten (Mechelen, Henry Jaye, 1621), p. LXX

- ↑ Anne-Laure Van Bruaene, "De Olijtak", in Repertorium van rederijkerskamers in de Zuidelijke Nederlanden en Luik 1400-1650 (digital publication, 2005). Accessed 25 Janu. 2015.