Oliver Hazard Perry

| Oliver Hazard Perry | |

|---|---|

The Hero of Lake Erie | |

| Born |

August 23, 1785 South Kingstown, Rhode Island |

| Died |

August 23, 1819 (aged 34) Trinidad |

| Place of burial | Newport, Rhode Island |

| Allegiance |

|

| Service/branch |

|

| Years of service | 1799–1819 |

| Rank | Commodore |

| Commands held |

|

| Battles/wars |

|

| Awards | Congressional Gold Medal |

| Relations |

|

United States Navy Commodore Oliver Hazard Perry (August 23, 1785 – August 23, 1819) was an American naval commander, born in South Kingstown, Rhode Island. He was the son of USN Captain Christopher Raymond Perry and Sarah Wallace Alexander, and the older brother of Commodore Matthew Calbraith Perry.

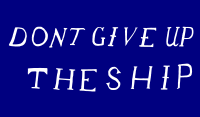

Perry served in the West Indies during the Quasi War with France, the Mediterranean during the Barbary Wars, in the Caribbean fighting piracy and the slave trade, but is most noted for his heroic role in the War of 1812 during the Battle of Lake Erie.[1] During the War of 1812 against Britain, Perry supervised the building of a fleet at Erie, Pennsylvania, at the age of 27. He earned the title "Hero of Lake Erie" for leading American forces in a decisive naval victory at the Battle of Lake Erie, receiving a Congressional Gold Medal and the Thanks of Congress.[2][3] His leadership materially aided the successful outcomes of all nine Lake Erie military campaign victories, and the fleet victory was a turning point in the battle for the west in the War of 1812.[3] He is remembered for the words on his battle flag, "Don't Give Up the Ship" and his message to General William Henry Harrison which reads in part, "We have met the enemy and they are ours; ..."

Perry became embroiled in a long-standing and festering controversy with the Commander of the USS Niagara, Captain Jesse Elliott, over their conduct in the battle, and both were the subject of official charges that were lodged. In 1815, he successfully commanded the Java in the Mediterranean during the Second Barbary War. So seminal was his career that he was lionized in the press (being the subject of scores of books and articles),[4] has been heavily memorialized, and many places and ships have been named in his honor.

Childhood and early life

As a boy, Perry lived in Tower Hill, Rhode Island,[5] sailing ships in anticipation of his future career as an officer in the US Navy.[3] He was the oldest of five boys, born to Christopher Perry, his father and Sarah Perry, his mother. Perry came from a long line of accomplished naval men from both sides of his family. His mother taught Perry and his younger brothers to read and write and had them attended Trinity Episcopal Church regularly, where he was baptized by Reverend William Smith at the age of nine. Theodore Dehon, rector of the church from 1797 to 1810 had a significant influence of the young Perry.[6] He was educated in Newport, Rhode Island.

Early naval career

By the age of twelve, Perry had sailed with his father to the West Indies and by at the age of 13 was appointed a midshipman in the United States Navy on April 7, 1799, aboard the USS General Greene, commanded by his father who was a captain. Their first stop was in Cuba to receive US merchant ships and provide them escort from Havana to the United States.[3][7] During the Quasi-War with France, he served on this frigate.[8] He first experienced combat on February 9, 1800, off the coast of the French colony of Haiti, which was in a state of rebellion.[9][10]

During the First Barbary War, he served on the USS Adams[11] and later commanded the USS Nautilus during the capture of Derna. Beginning in 1806, he commanded the sloop USS Revenge, engaging in patrol duties to enforce the Embargo Act, as well as a successful raid to regain a U.S. ship held in Spanish territory in Florida. On January 9, 1811, the Revenge ran aground off Rhode Island and was lost. "Seeing fairly quickly that he could not save the vessel, [Perry] turned his attention to saving the crew, and after helping them down the ropes over the vessel's stern, he was the last to leave the vessel." [12]:61 The following court-martial exonerated Perry, placing blame on the ship's pilot.[upper-alpha 1][13] In January 2011, a team of divers claimed to have discovered the remains of the Revenge, nearly 200 years to the day after it sank.[14][15]

Following the court-martial, Perry was given a leave of absence from the navy. On May 5, 1811, he married Elizabeth Champlin Mason of Newport, Rhode Island, whom he had met at a dance in 1807.[13] They enjoyed an extended honeymoon touring New England. The couple would eventually have five children, with one dying in infancy.[16]

War of 1812

At the beginning of the War of 1812 the British Navy controlled the Great Lakes, except for Lake Huron, while the American Navy controlled Lake Champlain.[17] American naval forces were very small, allowing the British to make many advances in the Great Lakes and northern New York waterways. The roles played by commanders like Oliver Hazard Perry, at Lake Erie and Isaac Chauncey at Lake Ontario and Thomas Macdonough at Lake Champlain all proved vital to the naval effort that provided the most redeeming military feature of that war. Naval historian E. B. Potter noted that "all naval officers of the day made a special study of Nelson's battles". Oliver Perry was no exception. [18] At his request he was given command of United States naval forces on Lake Erie during the War of 1812. U.S. Secretary of the Navy Paul Hamilton had charged prominent merchant seaman Daniel Dobbins with building the American fleet on Presque Isle Bay at Erie, Pennsylvania, and Perry was named chief naval officer.[2][3][19]

Perry knew battle was coming, and he "consciously followed Nelson's example in describing his battle plans to his captains."[18]:218 Perry's instructions were:

Commanding officers are particularly enjoined to pay attention in preserving their stations in the Line, and in all cases to keep as near the Lawrence as possible. ...Engage your designated adversary, in close action, at half cable's length. [upper-alpha 2][20]— Oliver H. Perry, General Order, USS Lawrence

Hero of Lake Erie

On September 10, 1813, Perry's command fought a successful fleet action against a task force of the Royal Navy in the Battle of Lake Erie. It was at the outset of this battle that Perry famously said, “If a victory is to be gained, I will gain it.”[21] Initially, the exchange of gunfire favored the British. Perry's flagship, the USS Lawrence, was so severely disabled in the encounter that the British commander, Robert Heriot Barclay, thought that Perry would surrender it, and sent a small boat to request that the American vessel pull down its flag. Faithful to the words of his battle flag, "DON'T GIVE UP THE SHIP" (a paraphrase of the dying words of Captain James Lawrence, the ship's namesake and Perry's friend),[22][23] Perry, with Lawrence's chaplain and purser as the remaining able crew, personally fired the final salvo,[24] and then had his men row him a half-mile (0.8 km) through heavy gunfire to transfer his command to the USS Niagara. Once aboard, Perry dispatched the Niagara's commander, Captain Jesse Elliot, to bring the other schooners into closer action while he steered the Niagara toward the damaged British ships. Like Nelson's Victory at Trafalgar, Niagara broke the opposing line. Perry's force pounded Barclay's ships until they could offer no effective resistance and surrendered. Although he had won the battle aboard the Niagara, he received the British surrender on the deck of the recaptured Lawrence to allow the British to see the terrible price his men had paid.[21] Perry's battle report to General William Henry Harrison was famously brief: "We have met the enemy and they are ours; two ships, two brigs, one schooner and one sloop."[22][upper-alpha 3]

This was the first time in history that an entire British naval squadron had surrendered, and every captured ship was successfully returned to Presque Isle.[25][26]

Although the engagement was small compared to Napoleonic naval battles such as the Battle of Trafalgar, the victory had disproportionate strategic importance, opening Canada up to possible invasion, while simultaneously protecting the entire Ohio Valley.[3][27] The loss of the British squadron directly led to the critical Battle of the Thames, the rout of British forces by Harrison's army, the death of Tecumseh, and the breakup of his Indian alliance.[26] Along with the Battle of Plattsburgh, it was one of only two significant fleet victories of the war.[3]

In fact, Perry was involved in nine battles that led to and followed the Battle of Lake Erie, and they all had a seminal impact. "What is often overlooked when studying Perry is how his physical participation and brilliant strategic leadership influenced the outcomes of all nine Lake Erie military campaign victories:" Capturing Fort George, Ontario in the Battle of Fort George; Destroying the British munitions at Olde Fort Erie (see Capture of Fort Erie); Rescuing five vessels from Black Rock; Building the Erie fleet; Getting the ships over the sandbar; Blocking British supplies for a month prior to battle; Planning the Thames invasion with General Harrison; Winning the Battle of Lake Erie; and Winning the Battle of Thames.[3][26]

Perry–Elliott controversy

Detroit and Queen Charlotte at right.

While Nelson had his Collingwood, Perry had his Elliott, and was considerably less well served. Jesse Elliott, while serving with Isaac Chauncey at Lake Ontario, was tasked to augment Perry's squadron with 11 officers and 91 men, "and none were sent but the worst."[28] Subsequently detailed by Chauncey to command Niagara, Elliott stated "that if he could have foreseen that he himself should be sent to Lake Erie, his selections would have been different."[28] Elliott then appropriated the "best of the worst" for Niagara; and Perry "in the interest of harmony" accepted the situation, though with growing ill-will.[28]

In his initial post-action report, Perry had praised Captain Elliott's role in the American victory at Lake Erie; and as news of the battle spread, Perry and Elliott were both celebrated as national heroes. Soon after, however, several junior officers publicly criticized Elliott's performance during the battle, charging that Elliott allowed the Lawrence to suffer the brunt of the British fire while holding the Niagara back from the fight. William Vigneron Taylor, Perry's sailing master, in a letter to Taylor's wife, put it thus:

The Lawrence alone rec'd the fire of the whole British squadron 2 1/2 hours within pistol shot—we were not supported as we ought to have been. Captain Perry led the Lawrence into action & sustained the most destructive fire with the most gallant spirit perhaps that was ever witnessed under similar circumstances.[29]— William Taylor, 15 September 1813

The meeting between Elliott and Perry on the deck of Niagara was terse. Elliott inquired how the day was going. Perry replied, "Badly." Elliott then volunteered to take Perry's small boat and rally the schooners, and Perry acquiesced.[20]:49 As Perry turned Niagara into the battle, Elliott was not aboard. Elliott's rejoinder to history's criticism of inaction was that there had been a lack of effective signaling. Charges were filed but were not officially acted upon. Attempting to restore his honor, Elliott and his supporters began a 30-year campaign that would outlive both men and ultimately leave his reputation in tatters.[26]

Congressional Gold Medal

On January 6, 1814, Perry was honored with a Congressional Gold Medal,[30] the Thanks of Congress, and a promotion to the rank of Captain.[31][32] This was one of 27 Gold Medals authorized by Congress arising from the War of 1812.[33]

|

|

Elliott was also recognized with a Congressional Gold Medal[30] and the Thanks of Congress for his actions in the Battle of Lake Erie. This recognition would prove to fan the flames of resentment on both sides of the Elliott–Perry controversy.[26]

In recognition of his victory at Lake Erie, in 1813 Perry was elected as an honorary member of the New York Society of the Cincinnati.

Later commands and controversies

Commodore Perry

In July 1814, Perry was offered command of the USS Java, a 44-gun frigate which was under construction in Baltimore. While overseeing the outfitting of the Java, Perry participated in the defenses of Baltimore and Washington, D.C. during the British invasion of the Chesapeake Bay. In a twist of irony, these land battles would be the last time the career naval officer saw combat. The Treaty of Ghent was signed before the Java could be put to sea.[16]

For Perry, the post-war years were marred by controversies. In 1815, he commanded the Java in the Mediterranean during the Second Barbary War. While moored in Naples, Perry was provoked into slapping the commander of the ship's Marines, John Heath. The ensuing court-martial found both men guilty but levied only mild reprimands. After the crew returned home, Heath challenged Perry to a pistol duel, which was fought on October 19, 1817, on the same Weehawken, New Jersey, field where Aaron Burr shot Alexander Hamilton. Heath fired first and missed. Perry refused to fire, satisfying the Marine's honor.[16]

Perry's return from the Mediterranean also reignited the feud with Elliott. After an exchange of angry letters, Elliott challenged Perry to a duel, which Perry refused. He instead decided to file formal court-martial charges against Elliott, including "conduct unbecoming an officer," and failure to "do his utmost to take or destroy the vessel of the enemy which it was his duty to encounter." Wishing to avoid a scandal between two congressionally decorated naval heroes, Secretary of the Navy Smith Thompson and President James Monroe suppressed the matter by offering Perry the rank of Commodore and a diplomatic mission to South America in exchange for dropping his charges against Elliott. This put an official end to the controversy, though it would continue to be debated for another quarter century.[36]

Death and legacy

Victory Quarter

In 1819, after a successful expedition to Venezuela's Orinoco River to consult with Simon Bolivar about piracy in the Caribbean, Perry contracted yellow fever from mosquitoes while aboard the USS Nonsuch. Despite the crew's efforts to reach Trinidad for medical assistance, the Commodore died on his 34th birthday as the ship was nearing Port of Spain. After being buried in Port of Spain, his remains were later taken back to the United States and interred in Newport, Rhode Island. After resting briefly in the Old Common Burial Ground, his body was finally moved to Newport's Island Cemetery,[37][38] where his brother Matthew C. Perry is also interred.[39]

Perry is shown on the reverse of the 2013 "Perry's Victory and International Peace Memorial Quarter". The reverse design depicts the statue of Perry with the International Peace Memorial in the distance.[40]

The family farm in South Kingstown, where Perry was probably born and later built a house, was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1982.[41]

Family

Perry's parents were Christopher Raymond Perry (1761–1818), who was also born in South Kingston, RI, and Sarah Wallace Alexander (1763-?). Through his mother, he was related to Scottish patriot William Wallace.[2]

Perry married Elizabeth Champlin Mason in 1811. They had five children, four of whom lived to maturity. They were:

- Christopher Grant Champlin Perry (April 2, 1812 – April 5, 1854) m. Murial Frances Sergeant of Philadelphia (great-granddaughter of Benjamin Franklin); their daughter Margaret Mason Perry married the artist John LaFarge;

- Oliver Hazard Perry II (February 23, 1813 – March 4, 1814) died in infancy;

- Oliver Hazard Perry, Jr. (February 23, 1815 – August 20, 1878) m. 1) Elizabeth Ann Randolph (1816–1847) (Virginia Randolph family) and m. 2) Mary Ann Moseley;

- Christopher Raymond Perry (June 29, 1816 – October 8, 1848) never married;

- Elizabeth Mason Perry m., as his 2nd wife, the Reverend Francis Vinton, rector of Trinity Episcopal Church in Newport.

Perry's son Christopher Grant Champlin Perry served as commander of the Artillery Company of Newport from 1848 until his death in 1854.

Oliver Hazard Perry, Jr. entered the Navy as a midshipman in 1829, rose to the rank of lieutenant and resigned in 1849.

Christopher Raymond Perry graduated from the United States Military Academy at West Point in 1842. He served during the Mexican War and fought at the Battle of Palo Alto on May 8, 1846 and at the Battle of Resaca-de‑la‑Palma on May 9, 1846. He died on active duty as a 1st lieutenant in 1848.[42]

His family's descendants include Commander John Rodgers, the second person to become a United States naval aviator,[43] and well known civilian aviator Calbraith Perry Rodgers, the first person to fly an airplane—the Vin Fiz—across the United States.[44]

Oliver Hazard Perry La Farge (December 19, 1901 – August 2, 1963) was an American writer and anthropologist, best known for his 1930 Pulitzer Prize–winning novel Laughing Boy.

His great nephew Oliver Hazard Perry Belmont (November 12, 1858 – June 10, 1908) was an American socialite and United States Representative from New York.

Oliver Hazard Perry Throck Morton (August 4, 1823 – November 1, 1877) (no relation)—the 14th Governor of Indiana, a famous Republican politician and U.S. Senator, who was a leader among the Radical Republican reconstructionists—was named in his honor.[45]

Geographical namesakes

Many locations, both in Rhode Island and near Lake Erie, are named in his honor, including:

Counties and municipalities (organized by state)

- All of the ten Perry counties in the U.S.

- Perryville and Perry County, Missouri

- The hamlet of Perrysburg and the surrounding township; and the Village of Perry, New York and the surrounding township,[46]

- The city of Perry, Georgia

- The Cities of Perrysburg, Perrysville, North Perry and Perry; Perrysburg Township; and Perry County, Ohio.

- The borough of Perryopolis and Oliver Township, within Perry County, and Oliver Township and Perry Township in Jefferson County, Pennsylvania.[47]

- The Village of Perryville in the Town of South Kingstown, Rhode Island. The portion of U.S. Route 1 near Perryville is named the Commodore Oliver Hazard Perry Highway and Perry Street in Newport.[48]

- The City of Hazard in Perry County, Kentucky.[49]

- Perry County, Tennessee

Monuments

Monuments to Perry are located in many locations, including:

- Perry's Victory and International Peace Memorial at Put-In-Bay, Ohio – 352 ft. (107 m) monument – the world's most massive Doric column – was constructed in Put-in-Bay, Ohio by a multi-state commission from 1912 to 1915.[50]

- Perry Monument at Misery Bay, Presque Isle State Park in Erie, Pennsylvania

- Front Park, by Charles Henry Niehaus, in Buffalo, New York, dedicated September 25, 1916

- Wade Park by William Walcutt, and Herman Matzen, in Cleveland, Ohio[51] Dedicated June 14, 1929

- Perry Square, monument designed by Paul Philippe Cret, in Erie, Pennsylvania, 1925

- Eisenhower Park in Newport, RI, statue by William Greene Turner, dedicated September 10, 1885, the 72nd anniversary of the Battle of Lake Erie.[52]

- Trinity Episcopal Church in Newport, RI, memorial plaque

- Rhode Island State House in Providence, RI, statue near the south front and a portrait in the Executive Chamber

- In April 1925, Captain Henry E. Lackey took the newly commissioned light cruiser USS Memphis (CL-13) and was the U.S. naval representative at the opening of the Oliver Hazard Perry Memorial Gateway in Port-of-Spain, Trinidad.[53][54]

Eponymous ships

Commodore Perry has been repeatedly honored with ships bearing his name.

- USS Perry (1843), a sailing brig 1843–1865.

- USS Commodore Perry (1859) was an armed side wheel ferry built in 1859 by Stack and Joyce, Williamsburg, N.Y. and purchased by the Navy October 2, 1861; and commissioned later in the month, Acting Master F. J. Thomas was in command.[55]

- USS Perry (DD-11), Bainbridge-class destroyer 1900–1919.

- USS Perry (DD-340), a Clemson-class destroyer converted into a high speed minesweeper and re-designated DMS–17 effective November 19, 1940. Served 1921–1944; sunk in Battle of Peleliu.

- Oliver Hazard Perry - USAT 2725 a Liberty ship. See List of Liberty ships (M–R).[56]

- USS Perry (DD-844), was a Gearing class destroyer 1945–1970.

- USS Oliver Hazard Perry (FFG-7), a guided-missile frigate 1976–1997 and Oliver Hazard Perry class frigates are named in his honor. The Navy built 51 of the Oliver Hazard Perry frigates, with the first going into service in 1977, and the last to be finally moth-balled in 2015.[57][58] See also USS Perry.

- SSV Oliver Hazard Perry Rhode Island Educational Foundation tall ship.

See also

- USS Niagara (1813)

- List of books about the War of 1812

- Bibliography of early American naval history

Notes

Footnotes

- ↑ His progression from being the subject of a court-martial for running aground to being a formidable commander who made a real difference has a striking parallel to the career of Admiral Chester W. Nimitz.

- ↑ A "cable" is 720 feet in the Royal Navy, 600 feet (183 m) in the U.S. Navy. "Half cable's length" would be less than 330 feet (100 m).

- ↑ The British order of battle was actually two ships, one brig, two schooners and one sloop.[24]:260–261 "Perry's message was inaccurate." [20]:Note 129, p. 97.

Citations

- ↑ Skaggs, 2006, p. xi

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 White, 1895, p. 288

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 Bloom, Page essay

- ↑ Paullin, 1918, See Bibliography

- ↑ Capace, Nancy (May 1, 2001). The Encyclopedia of Rhode Island. St. Clair Shores, Michigan: Somerset Publishers, Inc. p. 368. ISBN 9780403096107. Retrieved August 23, 2014.

- ↑ Skaggs, 2006, p. 6

- ↑ Mackenzie, 1840, p. 40

- ↑ Barnes, 1912, p. 11

- ↑ Brown, 2006, Oliver Hazard Perry, p. 226

- ↑ Barnes, 1912, p. 16

- ↑ Mackenzie, 1840, pp. 53-55

- ↑ Copes, Jan M. (Fall 1994). "The Perry Family: A Newport Naval Dynasty of the Early Republic". Newport History: Bulletin of the Newport Historical Society (Newport, RI: Newport Historical Society). 66, Part 2 (227): 49–77.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Cooper, James Fenimore (May 1843). Oliver Hazard Perry XXII (5). Graham's Magazine. p. 268. Retrieved January 7, 2011.

- ↑ "Divers: 1811 Wreck of Perry Ship Discovered Off RI". New York Times (Associated Press report). January 7, 2011. Retrieved January 7, 2011.

- ↑ "Divers Say They've Found 1811 Wreck of Perry Ship". AOL News. January 8, 2011. Retrieved January 9, 2011.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 "Oliver Hazard Perry – Perry's Victory & International Peace Memorial". Retrieved 9 June 2012.

- ↑ Skaggs, 2006, p. 50

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Potter, 1981, p. 106

- ↑ Herring, James; Longacre, James Barton (1854). The national portrait gallery of distinguished Americans 1. Philadelphia: D. Rice & A.N. Hart. Retrieved September 3, 2011.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 Altoff, Gerard T. (1999). Oliver Hazard Perry and the Battle of Lake Erie. Put-in-Bay, OH: The Perry Group. ISBN 978-1887794039.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Farmer, Silas. (1884) (Jul 1969) The history of Detroit and Michigan, or, The metropolis illustrated: a chronological cyclopaedia of the past and present: including a full record of territorial days in Michigan, and the annuals of Wayne County, p. 283 and Various formats at Open Library.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 "Famous Navy Quotes: Who Said Them and When". Naval History and Heritage Command. Retrieved September 3, 2011.

- ↑ Dudley, William S., ed. The Naval War of 1812: A Documentary History. vol.2 (Washington, D.C.: US Government Printing Office, 1992), p. 559.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Roosevelt, Theodore (1889). The Naval War of 1812 Or The History of the United States Navy during the Last War with Great Britain to Which Is Appended an Account of the Battle of New Orleans (Tenth ed.). New York: G. P. Putnum's Sons. p. 266.

- ↑ Skaggs, 2000, p. 147

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 26.3 26.4 Skaggs, David Curtis (April 2009). "Perry Triumphant". Naval History Magazine (United States Naval Institute) 23 (2). Retrieved September 3, 2011.

- ↑ Symonds, Craig L; Clipson, William J. (April 2001) The Naval Institute historical atlas of the U.S. Navy Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press 264pp, ISBN 978-1-55750-984-0; ISBN 1-55750-984-0, p. 48.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 Quoted in Altoff, Gerard T. (1993). Deep Water Sailors Shallow Water Soldiers: Manning the United States Fleet on Lake Erie – 1813. Put-in-Bay, OH: The Perry Group. pp. 23–24. ISBN 978-1887794015.

- ↑ Taylor, William V. (1813). Logbook of the USS Lawrence. Newport, RI: Newport Historical Society.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 J. F. Loubat, LL.D. (1831–1927) (1888). The Medallic History of the United States of America, 1776—1876. Volume II. Illustrated by Jaquemart, Jules Fredinand (1837–1880). N. Flayderman & Co. Retrieved September 3, 2011.

- ↑ Lossing, Benson J. (1869). "XVIII – Events on the Northern and Niagara Frontiers in 1812". Pictorial Field Book of the War of 1812. Retrieved September 3, 2011.

- ↑ "List of Congressional Gold Medal Recipients". Clerk of the U.S. House of Representatives. Retrieved September 3, 2011.

- ↑ Glassman, Matthew Eric, Analyst for the Congress (June 21, 2010). "Congressional Gold Medals, 1776–2009". p. 3. Retrieved September 3, 2011.

- ↑ Congressional Gold Medal Honoring Oliver Hazard Perry.

- ↑ Snowden, James Ross (1809–1878), Director of the Mint: United States Mint (1861). A Description of the Medals of Washington; and of other Objects of Interest in the Museum of the Mint. Illustrated, to which are added Biographical Notices of the Directors of the Mint from 1792 to the year 1851. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: J. B. Lippincott & Co. pp. 83–84. Retrieved September 3, 2011.

- ↑ Skaggs, David Curtis (2006). Oliver Hazard Perry: Honor, Courage, and Patriotism in the Early U.S. Navy. Naval Institute Press. pp. 191–199. ISBN 978-1-59114-792-3. Retrieved September 3, 2011.

- ↑ Drake, Samuel Adams,1833–1905. Nooks and corners of the New England coast, Rhode Ialand Cemeteries, p. 401.

- ↑ Oliver Hazard Perry at Find a Grave

- ↑ "Matthew Calbraith Perry (1794–1858) – Find a Grave Memorial". Retrieved January 9, 2011.

- ↑ United States Mint. "Perry's Victory and International Peace Memorial". United States Mint. Retrieved 8 June 2013.

- ↑ "82000020 NRHP nomination for Commodore Oliver Perry Farm" (PDF). Rhode Island Preservation. Retrieved 2014-09-30.

- ↑ Christopher R. Perry. "Christopher R. Perry • Cullum's Register • 1163". Penelope.uchicago.edu. Retrieved 2013-07-10.

- ↑ "John Rodgers, Commander, United States Navy". Arlington National Cemetery Website. Retrieved January 9, 2011.

- ↑ Patricia Clark. "Calbraith Rodgers". Pennsylvania Center for the Book, Penn State. Retrieved January 9, 2011.

- ↑ Woollen, William Wesley (1975). Biographical and Historical Sketches of Early Indiana. Ayer Publishing. p. 129. ISBN 0-405-06896-4. Retrieved February 16, 2009.

- ↑ Perry, New York at epodunk.com.

- ↑ Espenshade, Abraham Howry (1925). Pennsylvania place names. Pennsylvania State College. p. 337.

- ↑ Capace, Nancy (May 1, 2001). The Encyclopedia of Rhode Island. St. Clair Shores, Michigan: Somerset Publishers, Inc. pp. 160, 360, 363. ISBN 9780403096107. Retrieved August 23, 2014.

- ↑ Bergstrom, Bill (December 11, 1984). "Origins of place names are traced". Kentucky New Era. pp. 2B. Retrieved 29 April 2015.

- ↑ Watterson, Henry (1840–1921) (1912). The Perry memorial and centennial celebration under the auspices of the national government and the states of Ohio, Pennsylvania, Michigan, Illinois, Wisconsin, New York, Rhode Island, Kentucky, Minnesota and Indiana. Cleveland, Ohio: Interstate Board of the Perry's Victory Centennial Commissioners. Retrieved October 22, 2011.

- ↑ Glazier, Capt. William (1886). Peculiarities of American Cities. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Hubbard Bros. p. 156. Retrieved June 17, 2011.

- ↑ Olshan, Matthew (August 20, 2009). "A tale of two statues: A reader’s story about Newport’s Perry monuments prompts an investigation by a Pennsylvania writer". The Newport Daily News (Newport, RI). pp. A9.

- ↑ "Papers of Rear Admiral Henry E. Lackey (1899–1940)". Washington, D.C: Operational Archives Branch, Naval Historical Center. Retrieved September 2, 2011.

- ↑ "USS Memphis". historycentral.com. Retrieved September 2, 2011.

- ↑ "Commodore Perry". The Naval Historical Center. Retrieved September 3, 2011.

- ↑ Liberty Ships built by the United States Maritime Commission.

- ↑ Vergakis, Brock (January 7, 2015). "Last deployment: All Navy frigates soon to be decommissioned". Associated Press. Retrieved January 7, 2015.

- ↑ Rogoway, Tyler (January 10, 2014). "End Of The 'Ghetto Navy' Is In Sight As Last USN Frigate Cruise Begins". Fox Trot Alpha. Retrieved January 10, 2014.

Bibliography

- Barnes, James (1912). The hero of Erie: (Oliver Hazard Perry). D. Appleton & Company, New York, London, p. 167. E'book

- Bloom, Loren (2008). "Oliver Hazard Perry – Hero". Erie Maritime Museum. Retrieved August 25, 2011.

- Brown, John Howard. The Cyclopaedia of American Biography: Comprising the Men and Women of the United States ..., V6. Kessinger Publishing,. p. 700. ISBN 978-1-4254-8629-7., Book

- Mackenzie, Alexander Slidell (1910). Commodore Oliver Hazard Perry:. D.M. MacLellan Book Company, New York, NY/Akron, OH. p. 443. E'book

- Mackenzie, Alexander Slidell (1840). The life of Commodore Oliver Hazard Perry 1. New York: Harper & Brothers. p. 443. E'book

- Paullin, Charles Edward (1918). The Battle of Lake Erie (a collection of documents, mainly those by Oliver Hazard Perry). Cleveland, Ohio: The Raufin Club. Retrieved August 18, 2011.

- Potter, Elmer Belmont (1981). Sea Power: A Naval History. Naval Institute Press. p. 419. ISBN 9780870216077., Book

- Skaggs, David Curtis (2006). Oliver Hazard Perry: honor, courage, and patriotism in the early U.S. Navy. Naval Institute Press. p. 302. ISBN 1-59114-792-1. Url

- Skaggs, David Curtis; Altoff, Gerard T. (2000). A Signal Victory: The Lake Erie Campaign, 1812-1813. Naval Institute Press,. p. 264. ISBN 9781557508928.

- White, James T. (1895). Oliver Hazard Perry. National Cyclopaedia of American Biography. p. 288,., Book

Further reading

- Axelrod, Alen; Phillips, Charles. The Macmillan Dictionary of Military Biography (New York: Macmillan, 1998.) p. 343.

- Bancroft, George, 1800–1891; Dyer, Oliver, 1824–1907. (1891) History of the battle of Lake Erie: and miscellaneous papers (New York : R. Bonner's sons) 292 pp. at American Library Association.

- Burges, Tristam (1770–1853) (1839) Battle of Lake Erie, with notices of Commodore Elliot's conduct in that engagement (Providence, Brown & Cady) at Internet Archive.

- Conners, William James, 1857–; Emerson, George Douglas. (1916) The Perrys victory centenary. Report of the Perry’s victory centennial commission, state of New York (Albany, J.B. Lyon Company, Printers).

- Coles, Harry L; Borstin, Daniel J., eds. August 1966 The War of 1812 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press) ISBN 978-0-226-11350-0.

- Cooper, James Fenimore (1846) Lives of Distinguished American Naval Officers Kingman Press and here for American Library Association.

- Cooper, James Fenimore, History of the Navy (1839).

- Dillon, Richard. (1978) We have met the enemy: Oliver Hazard Perry, wilderness commodore (New York: McGraw-Hill). ISBN 978-0-07-016981-4.

- "Robert J. Dodge Collection – MS 157". Center for Archival Collections. Bowling Green State University. Retrieved October 2, 2011.

- Dodge, Robert J. (1962). The Battle of Lake Erie. National Park Service.

- Dutton, Charles J.(1935) Oliver Hazard Perry (New York: Longmans, Green and Co.) 308 pp. (Scholar's Bookshelf; First Edition. October 15, 2006) ISBN 0-945726-36-8; ISBN 978-0-945726-36-4.

- Downloadable resources regarding Oliver Hazard Perry, American Library Association.

- Eaton, Joseph Giles (1847–1905) (1905) Perry's Victory on Lake Erie. Military Historical Society of Massachusetts (Boston, For the Society, by Houghton Mifflin)at American Library Association.

- Elliott, Jesse D. Address of Com. Jesse D. Elliot, U.S.N., Delivered in Washington County, Maryland, to His Early Companions at Their Request, on November 24, 1843 (Philadelphia: G.B. Zeiber & co., 1844) 137 pp. at Google books.

- Hickey, Donald R. (1990) The War of 1812: The Forgotten Conflict Urbana, Illinois: University of Illinois Press. National Historical Society Book Prize and American Military Institute Best Book Award. ISBN 0-252-06059-8; ISBN 978-0-252-06059-5.

- Hickey, Donald R. (2006) Don't Give Up the Ship! Myths of the War of 1812. (Urbana: University of Illinois Press) ISBN 0-252-03179-2.

- Langguth, A. J. (2006). Union 1812: The Americans Who Fought the Second War of Independence. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-7432-2618-6.

- Lyman, Olin H. (1905) Commodore Oliver Hazard Perry and the War on the Lakes.

- Mackenzie, Alexander Slidell 1803–1848. (1915) Commodore Oliver Hazard Perry : famous American naval hero, victor of the battle of Lake Erie, his life and achievements (Akron, Ohio: Superior Printing Co.) at Internet archive.

- Mackenzie, Alexander Slidell, 1803–1848 (1840) The life of Commodore Oliver Hazard Perry. (New York, Harper) Volume 1, Volume 2.

- Mahan, Alfred Thayer (1840–1914)(1905) Sea Power in Its Relation to the War of 1812 (2 vols.) (Boston: Little Brown) American Library Association.

- Niles, John Milton (1820). The Life of Oliver Hazard Perry.

William S. Marsh, Hartford. p. 376., E'book - Paullin, Charles Edward (October 1918). The Battle of Lake Erie (a collection of documents, mainly those by Oliver Hazard Perry). Cleveland, Ohio: The Raufin Club. Retrieved August 18, 2011.

- Morton, Edward Payson (1869–1914) Lake Erie and the story of Commodore Perry Chicago: Ainsworth & company Internet Archive digitized by Google.

- Niles, John Milton (Bedford, Mass.: Applewood Books, 1830) The Life of Oliver Hazard Perry.

- Reid, George. (1913) Perry at Erie:how Captain Dobbins, Benjamin Fleming and others assisted him. (Erie, Pennsylvania: Journal publishing company).

- Skaggs, David Curtis; Altoff, Gerard T. Altoff A Signal Victory: The Lake Erie Campaign, 1812–1813 (Naval Institute Press), winner John Lyman Book Awards 1997. ISBN 978-1-55750-892-8.

- Skaggs, David Curtis; Welsh, William Jeffrey, editors (1991). War on the Great Lakes: Essays Commemorating the 175th Anniversary of the Battle of Lake Erie. Kent State University Press. Retrieved May 24, 2012.

- Skaggs, David Curtis. Perry Triumphant (April 2009 Volume 23, Number 2) Naval History Magazine United States Naval Institute.

- White, James T. (1895) p. 288. National Cyclopaedia of American Biography.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Oliver Hazard Perry. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Oliver Hazard Perry |

- Bibliography Paullin, Charles Edward (October 1918). The Battle of Lake Erie (a collection of documents, mainly those by Oliver Hazard Perry). Cleveland, Ohio: The Raufin Club. Retrieved August 18, 2011..

- Perry @ the National Park Service.

- Perry @ the Naval Historical Center.

- Perry's account of the Battle of Lake Erie (See Further reading, Pauilin, supra.)

- The Oliver Hazard Perry papers William L. Clements Library.

- "Log of the Battle of Lake Erie" by Sailing Master William Taylor.

- US Brig Niagara

- Commodore Perry I.P.A. and Tasting guide, Commodore Perry India Pale Ale by Great Lakes Brewing Co.

- Bloom, Loren (2008). "Information about the epic battle painting by Julian O. Davidson". The Battle of Lake Erie: Julian Oliver Davidson's Painting. Erie Maritime Museum. Retrieved August 25, 2011.

- Perry Monument, Buffalo Historical Markers and Monuments website.

- Oliver Hazard Perry at Find a Grave

- Oliver Hazard Perry at Rootsweb.

- Correspondence of Oliver Hazard Perry at Dartmouth Digital Library

|