Old Manor Hospital, Salisbury

| Old Manor Hospital (formerly Fisherton House Asylum) | |

|---|---|

|

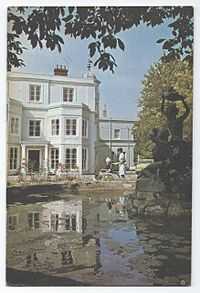

Main entrance of the Old Manor Hospital taken in about 1974 | |

| |

| Geography | |

| Location | Salisbury |

| Coordinates | 51°04′22″N 1°48′37″W / 51.072792°N 1.810212°WCoordinates: 51°04′22″N 1°48′37″W / 51.072792°N 1.810212°W |

| Organisation | |

| Care system | UK:NHS from 1955 |

| Funding | Government (formerly private) |

| Hospital type | Specialist |

| Services | |

| Speciality | Psychiatry |

| History | |

| Founded | 1813 |

| Closed | 2003 |

The Old Manor Hospital was a psychiatric hospital in Salisbury, Wiltshire, England. It functioned first as a Victorian private licensed house called Fisherton House or Fisherton House Asylum from the early 19th century. It was the largest private madhouse in the United Kingdom. In 1924 following a change of proprietors it was renamed Old Manor Hospital and in 1955 it was amalgamated into the National Health Service. From 1813 to 1955 it was owned and managed by members of the same family. The Old Manor Hospital closed in 2003 and was replaced by Fountain Way, a smaller, modern, psychiatric hospital on part of the site of the Old Manor Hospital.

Founding and early history

In the early 19th century Dr. William Corbin Finch, a London surgeon, bought Fisherton House in the village of Fisherton Anger, a village to the west of Salisbury. At that time it was outside the city but due to urban development the site is now within the city of Salisbury on the lower part of Wilton Road. It is recorded that patients were received in 1813 and Fisherton House was sold as a "mental institution" to Charles Finch in 1813.[1]

According to William Parry-Jones in his book (The Trade in Lunacy, A Study of Private Madhouses in 18th and 19th Century Britain) the asylum did not appear on an 1815 list of businesses in Salisbury but was certainly functioning by 1826.[2] At that time William Corbin Finch also owned Laverstock House, in a village east of Salisbury, and Kensington House and The Retreat in The Kings Road in London, all licensed madhouses.[2] Dr Finch also gave evidence to the 1815 Select Committee who were investigating conditions in private madhouses across England. Their report came to nothing due to lack of co-operation of the asylums.[3]

Fisherton House was subject to the Madhouses Act of 1774 which prescribed certain rules and conditions regarding private asylums run for profit. Briefly, asylums had to notify the Metropolitan Commissioners of Lunacy of any admissions, this was to maintain a countrywide register, asylums had to be supervised by a qualified doctor and submit to regular inspections by the local Quarter Sessions. The 1828 Madhouse Act superseded the 1774 Act and made provision for local magistrates to visit 4 times each year to inspect the condition, provision of care and regulation of the asylum. There was a securely bound "Visitors' Book" in which the visiting magistrates were obliged to record anything they regarded as important, whether positive or negative.[4] One of the sections of the Madhouses Act of 1774 provided that a person could be admitted to an asylum on a single certificate signed by a physician, surgeon or apothecary of unspecified qualification. In 1815 William Corbin Finch expressed concern, with other asylum owners, about the literacy of some apothecaries. He illustrated this with an admission note he had received from a local apothecary:

- "Hey Broadway, A Potcarey of Gillingham Certefy that Mr James Burt misfortin hapened by a Plow in the Hed which is the Ocaisim of his Ellness & By the Rising and Falling of the Blood And I think a Blister and bleeding and meddeson Will be A Very Great Thing But Mr James Burt wold not A Gree to be Don at Home. Hay Broadway."[2]

When first opened Fisherton Asylum took private and pauper patients and was superintended by Mr Charles Finch (uncle of William Corbin Finch) who in 1828 placed an advertisement in a local newspaper, The Salisbury & Winchester Journal: (original spelling and grammar retained)

- “FISHERTON ASYLUM, NEAR SALISBURY. For the Reception of INSANE PATIENTS, under the immediate Superintendence of Mr. CHARLES FINCH, who for upwards of twenty five years has devoted his time and study to relieve those afflicted with mental disorder and aberration. Mr. C. FINCH returns his grateful acknowledgments to the Medical Gentlemen and the Public for the very great patronage he has experienced, and informs them he has completed some extensive and important improvements in and around the Asylum, for the better classification and comfort of its inmates, and for the appropriate accommodation of persons of the greatest respectability. The recovery of his patients and their restoration to their friends and to society has ever been a primary object of solicitude with Mr. C. FINCH, and he can adduce many proofs that his endeavours to attain this object have been eminently successful. He has found, in his experience, that incurable cases are by no means so numerous as is generally imagined, particularly in aberrations resulting from febrile attacks: with those patients who have youth on their side, or whose malady is but of recent date, there is abundant room to hope that with judicious treatment a complete cure may be effected. The apartments in the Asylum destined for male and female patients, are distinct and separate, by which arrangement all keep a belief that their sufferings receive sympathy and commiseration from those under whose care they are placed. To insure the greatest attention and domestic comfort to the afflicted, with treatment suited to the various forms of the disease, Mr. and Mrs. FINCH constantly reside in the Establishment so that nothing is entrusted to menials, which is the surest preventative of irregularity, disquietude, and improper treatment. Very extensive Pleasure Grounds and Gardens, which have been recently much enlarged, and at a great expence improved and diversified, form a distinguishing portion of the Establishment; and are so studiously laid out as to produce a pleasing variety of amusement and promenade, and to gratify the patients' natural desire for change; to all of which they have an unlimited access. The Attendants are carefully selected, and of approved humanity and kind disposition. There are convenient distinct Buildings for Pauper Patients, who are admitted as usual, and receive every possible Medical attendance and kind treatment equal to any Establishment in the Kingdom.” – June 1836[5]

By 1837 there were 100 inmates of which 60 were paupers, paid for by local government funds.[2] and following the passing of the Criminal Lunatics Act in 1800, initiated by the attempted assassination of King George III, an increasing number of patients were being sent from criminal courts to be detained “until his Majesty's pleasure be known” in Bethlem Hospital and a few to Fisherton House. Over the next decade the asylum did not expand with still 100 licensed places in 1847. In 1848 the proprietors agreed to build special wards to take the less dangerous criminal lunatics that were scattered in asylums around the country. Bethlem hospital would take the more dangerous patients. The fifth annual report by the Lunacy Commissioners found that the numbers of criminal lunatics had increased and the relief provided by Fisherton House inadequate. Lord Shaftesbury called for the construction of a special asylum to house all criminal lunatics – to no avail.[6] In 1850 the Commissioners' Report noted that Fisherton House was one of three provincial licensed houses that was "defective". The poor conditions were due to overcrowding caused by the transfer of "harmless criminal lunatics" from Bethlem Hospital when it became overcrowded. The poor conditions were tolerated because of the expectation of paupers being transferred to the newly commissioned county asylums.[2] (following the Lunacy Act 1845 promoting the construction of county asylums). In 1853 it is recorded that Fisherton House had 214 patients cared for by 26 attendants.[2] At that time Fisherton House was accepting pauper admissions from boroughs well beyond Wiltshire.[2] Dr Corbin Finch (snr), the medical superintendent, was a city alderman (1842–56), Mayor of Salisbury in 1842[7] and had proposed the building of St Paul's Church in Salisbury as well as being a senior physician at Salisbury Infirmary. He died in 1867 in Salisbury.[8] He was succeeded by his son, Dr William Corbin Finch (jnr). In 1862 the Corbin Finch family were joined in business by Dr John Alfred Lush, a local family doctor who had married the sister of William Corbin Finch (jnr) in 1853. He set up a private practice in Salisbury and later joined the management staff of Fisherton House. He went on to be Liberal MP for Salisbury (1868–80) and President of the Medico-Psychological Association.

The Glasgow Herald printed in 1864 part of an article from The Cornhill Magazine which describes some aspects of Fisherton Asylum life. The article describes encounters with inmates, medical staff and an inmates' social ball and gives a generally favourable impression.[9]

When the Wiltshire County Asylum had become established in the 1860s pauper patients resident in Wiltshire were transferred there but the patient numbers were maintained by taking pauper patients from Portsmouth and Middlesex unions.[10]

The Prince of Wales, (later Edward VII) visited Fisherton House during the autumn of 1870.[11] The local paper announced the visit thus:

- “We understand that His Royal Highness, The Prince of Wales will visit the city to be present during the army manoeuvres on Salisbury Plain on 3 Sept.. and will remain until the 10th of that month. His Royal Highness will take up residence in Bemerton Lodge which has been placed at his disposal through Dr Lush by Mr William Corbin Finch."[3]

A large ballroom had been constructed in 1868/69 as a patients' social activities room. This was used on at least one occasion as a venue for a concert for the entertainment of the prince and his entourage.[11]

Working and visiting at Fisherton Asylum was not without hazard. In 1873 Mr Robert Wilfred S Lutwidge, uncle of Charles Lutwidge Dodgson, was visiting the asylum with others in his capacity of Commissioner in Lunacy when he was attacked by a patient and later died. William McCave, had pretended to be asleep and when Lutwidge passed he struck him in the head with a large nail, he claimed his motive was to attain transfer to Broadmoor Hospital.[12]

In 1877–78 Dr John Lush, then superintendent, sat on a parliamentary Select Committee enquiring into the Lunacy Act so far as regards security afforded by it against violations of personal liberty.[13]

From 1878–90 Fisherton House was licensed to receive 672 patients, some of which were paupers, some were private, and some were criminal lunatics. This made it the largest private madhouse ever to have existed in the United Kingdom.[2]

In 1880 a number of patients at Fisherton House from Portsea Island union workhouse area were transferred to the newly opened Portsmouth Lunatic Asylum (later St James Hospital)[14] but pauper patients from the Middlesex workhouse union were being admitted and remained until at least 1888.

In the late 19th century it was not unusual to have children confined in the asylum. There is evidence in records that children were sent from the London and Birmingham unions for care at Fisherton Asylum. This young man survived for two years and the other was discharged after 1 year.

After a Commissioners' Visit in 1883 Dr Finch received a complaint about "rough handling" of some female patients. They found the wards tranquil but felt "The Female Head Attendant was overtasked" and it was suggested she be replaced as a supervisor of other attendants. Some female patients complained of "blows and twisting of arms" and the Commissioners suggested that the Head Attendant should visit the women's wards more often. They also suggested that medical staff should keep these wards under observation. The Commissioners requested that Dr Finch make staff aware that they could be dismissed for such conduct in the future. No official summons was made against the asylum. The following visit noted improvements, two medical staff had been appointed to assist Dr Richard Finch, who was Medical Superintendent at this time, and second cousin of Dr William Corbin Finch jnr. He replaced Alfred Lush who had retired and died in 1888 A further report in 1896 notes 669 patients in the asylum, the licence permitted 672. There were 135 private patients and 534 paupers paid for by local authorities. Among the pauper patients were 263 who were charged to London unions, 263 to West Sussex and 29 to Canterbury in Kent, some 140 miles distant. The commonest reason for their presence was full asylums locally. The inspectors noted some unexplained bruising of some patients, seclusion was still being used, the giving of "white medicine" was condemned and concern was expressed about washing facilities, smelly bathrooms and lack of ventilation.[3] Richard Tanner Finch was still the Medical Superintendent.[15]

The 20th century

The property and business of Fisherton House was transferred in 1904 by Dr W Corbin Finch jnr. to the last of the Finches, his daughter, Francis Emily (later Mrs Baskin) who took over the business in 1905 on the death of her father.[3]

In 1916 Richard Tanner Finch was still medical superintendent as many documents signed by him can attest. He was assisted by Dr Joseph Percival Westrup and in 1918 they were joined by Dr A C King Turner. Dr Tanner Finch left in 1919 and was succeeded as physician superintendent by Dr King Turner.[16] A Dr Wills was appointed in 1920.

In 1921 Samuel Edgar Martin, MB B.Ch., Barrister at Law was appointed Physician Superintendent, from St. Andrews Mental Hospital in Northampton. He was born in County Down, Northern Ireland. He looked after patients at both Fisherton Asylum and Laverstock House. He regularly recruited attendants from the Republic of Ireland, especially from the Ennis, County Clare area from where new staff arrived to work with family and friends already employed. Dr Martin was once attacked by a patient with a penknife during his rounds, the assailant had been a solicitor at the infamous Dr. Crippin murder trial. The patient was transferred to Broadmoor Hospital. Dr Martin held the position of Physician Superintendent until 1952. According to visitors reports all continued satisfactorily with "all modern treatments available". In paperwork private patients were referred to as 'ladies' and 'gentlemen' and state financed patients were called 'male' and 'female'.[3]

In 1924 the Fisherton House Asylum suffered some financial difficulties and a limited company was formed called Old Manor (Salisbury) Ltd. Sir Cecil Chubb was appointed managing director and left his law practice to concentrate wholly on the management of the business.[3] Sir Cecil Chubb had been cited as being the "proprietor" of the hospital in 1918[16] Other members of the board were Lady Mary Chubb, wife of Sir Cecil and daughter of Dr William Corbin Finch jnr., W F Swords KC, (son-in-law of Dr William Corbin Finch jnr., Mr Vivian Barker, a Lloyds Bank manager and Mr A J Belsham, a solicitor.[3]

Sarum Ward and New Sarum ward were built just before 1923 when a number of Service Patients were admitted. These were former members of the armed forces who had sustained a mental disorder, from World War I. Records show that others had been in the Boer War and a few from the Crimean War. A further influx of Service Patients were admitted in 1931 from the Ministry of Pensions Hospital in Kirkburton, Yorkshire. These were all lower ranks and were housed in the aforementioned wards. Some officers from Latchmere House in Surrey were also admitted around this time and they were accommodated in Bemerton Lodge, the former residence of William Corbin Finch and Sir Cecil Chubb. Service patients were treated as private patients and their charges were met by the Ministry of Pensions. within the constraint of the institution they lived fairly comfortable lives with a range of hobbies, a weekly film show in the ballroom and other social diversions available as well as annual trips to public entertainments courtesy of the Not Forgotten Association.[3][17]

In 1924 The Royal Commission on Lunacy and Mental Disorders[18] issued a report which led to the Mental Treatment Act of 1930. This report affected the running of the hospital to the extent that patients had improved rights which allowed them to enter or leave the hospital at will, unless they were suffering from a condition that had demonstrable reasons to detain the patient. There was also a change in some terminologies; "asylum" was replaced by "hospital" and "inmate" by "patient" for example. No great recorded changes ensued in the Old Manor.

An inspection report of around 1940 noted 5 doctors, 25 registered nurses and 23 assistant male staff. On the female side were 10 registered nurses and 3 part-time registered nurses, with 31 assistant nurses and 10 part-time assistant nurses. At this time the annual licensing fee for the hospital was 10 shillings(50 new pence) per patient, a total of £336.[3]

Conditions appear good in 1942 when a further commissioners' report notes "I have found on the whole the patients were happy and contented, obviously enjoying careful and kindly treatment … There were 40 male staff when there should have been 60 … Patients are well occupied and parole is liberally given. We regret to record the death of a male charge nurse who died as a result of a homicidal attack by one of the male patients".[3] This incident occurred in the Old Manor in 1941, a patient, Norman Ashton, struck a member of staff, Reginald Trubridge, over the head with an iron grating in the kitchen of one of the wards. It transpired at the initial trial that Ashton had a grievance against Trubridge and the hearing was transferred to the Old Bailey. During the subsequent court hearing Mr Ashton was declared unfit to plead and was detained at His Majesty's Pleasure.[19]

The National Health Service was formed in England and Wales in 1948 and the Old Manor Hospital fell within the South West Metropolitan Region for Ministry of Health administrative purposes.[20] In 1952 the hospital again suffered financial problems. Vivian Bell an ex-RAF officer was appointed as administrator and Dr G O Cowdy was appointed as a senior medical officer in January 1952 when Dr Samuel Martin retired. However, at a company meeting in Lincoln's Inn on 21 April 1954 it was agreed that the Old Manor Hospital should be wound up as a private business.[21] The hospital was duly purchased by and amalgamated into the NHS. It was managerially supervised by Knowle Hospital in Fareham, Hampshire. Headed by Dr Galbraith, the then Knowle Hospital medical superintendent. Mr Gordon-Orr was appointed the first hospital Secretary.[3]

The last matron to be employed at The Old Manor was Miss Mavis Arnold. A local girl, she commenced her post as matron in 1953 and brought a caring but stern attitude to staff management, she displayed a warmth and sense of humour but maintained firm discipline. A tall distinctive figure with her immaculate grey uniform and high starched cap she was the epitome of a matron at that time. At this time all wards were still locked, and the doors in the periphery wall were also locked. It was not until about 1970 that most wards were open and access to the hospital site was unrestricted. The last Principal Nursing Officer was Mr Frederick Frank Forder, he was appointed in 1957 and managed the male side of the hospital while Matron Arnold was in post but took responsibility for the whole hospital on her retirement.[22]

There was a surge of building development from April 1968 when a new 25-bedded Nightingale Ward was built and opened by the Chairman of the Wessex Regional Hospital Board, Mr P L Templeman. This was followed in April 1971 by a newly built 35-bedded Crane Ward opened by the Lord Lieutenant of Wiltshire Lord Margadale of Islay. The old adjoined wards that were vacated were then refurbished and opened as Linford Ward by Mrs Hilda Barker, the Mayor of Salisbury as a modern facility for elderly mental healthcare.[11]

1974 saw a further reorganisation in the hierarchical structure of the NHS and the management of the Old Manor Hospital fell within the Salisbury Health District, as part of the Wessex Regional Health Authority. Several years later it became part of the Community Services Division of the Salisbury Health Care NHS Trust.[20]

In the modern era there was a drive to open the hospital and find appropriate accommodation for patients who had no need for the institutional care of the hospital. A consultant and an experienced social worker reviewed all the long term patients and selected those that were thought suitable for rehabilitation to self-dependence and a sheltered accommodation in the city. Some Polish service patients were returned to their families in Poland. In all some 200 patients were discharged to the community with support from local families, landladies, hospital day facilities and psychiatric community nurses.

The Salisbury Journal produced a full page feature in May 1978 reporting that there were now 7 full-time psychiatric community nurses working with a team of social workers covering a 300,000 population caring for and supporting patients living at home. Kennet Lodge (formerly Pembroke Lodge) was preparing long stay patients for discharge by a regime of minimal carer intervention, encouragement of individual independence and the opportunity to work in the workshop within the hospital which fulfilled a range of sub-contracts from private firms to assemble items and package items. The money earned was paid to the patients and went towards annual holidays at local seaside resorts. The number of beds was now below 300 and the day hospital for the elderly, New Sarum, was functioning well, later to be replaced with a newly built Elizabeth Barker Day Hospital following an appeal by the ex-mayor.[23]

By the 1990s there were few Service Patients remaining and the Department of Health encouraged the treatment of mental health problems within the community. Modern medicines ensured better control of symptoms and an outreach team assisted in preventing admission. The wards were gradually closed within the hospital until by the start of the 21st century a smaller new facility was planned and commissioned and the Old Manor closed.

Care and treatment

At its foundation it is likely, in common with many others, that Fisherton House Asylum offered little more than basic physical care, security for the individual and a refuge from society. It also afforded some protection to the public from persons whose behaviour may have been dangerous or disconcerting. Doctors had little understanding of what caused mental illness and their prescriptions for treatment in the early days were based on personal experience. Physical restraint was a common method of controlling dangerous behaviour, either by leg manacles, handcuffs or straitjackets, but these had been largely discontinued by 1847. Among other treatments later recorded in use in Fisherton House in the mid-19th century were cupping, blistering, purging, diuretics, bleeding and the giving of various unspecified drugs. Some patients were subject to induced vomiting twice a week. For mania a tartar emetic "worked briskly", arsenic, opium and creosote were also used.[3]

From a Commissioners Report in 1847 it is recorded that local bleeding, cold to the bare head and warmth to the lower extremities, opium, croton oil, hop pillows, prolonged warm baths with wooden planks across the bath to permit the taking of meals, setons to the neck (insertion of absorbent stitches to drain 'noxious substances' from the brain), a generous diet, malt liquor, wine and fresh air were all used as methods of treatment.[3] Each ward had a walled exercise garden around which was a high wall to prevent escape, this served to provide an area where patients could exercise and enjoy the planted borders.[9]

In 1880 paraldehyde was used for the first time in Fisherton House, the use of this drug continued into the latter half of the 20th century. There was no pharmacist or dispenser, the asylum matron was responsible for dispensing medication. Generally treatment of patients reflected current trends, but some seclusion and mechanical restraint was occasionally used.[3]

In the 1940s electroconvulsive therapy was used for the first time in the hospital, in the 1950s modified insulin therapy was also used. These treatments coincided with the advent of specific psychotropic drugs such as chlorpromazine, thioridazine, lithium carbonate and tricyclic antidepressants being used. In common with other psychiatric hospitals treatment included, occupational therapy, group therapy and a gradually increasing range of antidepressants and psychotropic drugs, some of which were available in long-acting forms which ensured better medication compliance.[3][22]

During the 1950s and 1960s the hospital remained a secure institution where patients were protected from the outside world. Almost all wards were locked and patients were reliant on staff to go in and out. All staff carried keys and the emphasis was on custody before therapy.[22]

The late 1950s saw the development of an industrial therapy unit which provided a factory style milieu to encourage patients' occupation and change of environment. Longer-stay patients began taking holidays away from the hospital accompanied by staff.

By the late 1960s there were day-patients coming into the admission wards for the day and going home at night. A designated day hospital was set up in the late 70s where all day-patients attended one centre and appropriate support staff could be concentrated for integrated therapeutic effect. In the late 1970s there arose a plan to discharge a significant number of patients who had been at the hospital for decades and who had to various degrees lost their social and daily living skills. Under the supervision of a consultant and a senior social worker all suitable patients were interviewed and assessed for their suitability for discharge. A campaign was opened to find suitable accommodation with sympathetic families or landladies in the community of Salisbury.

Attendant/nurse training

There is no formal training recorded for attendants in Fisherton House Asylum until 1923 when the Medico-Psychological Association (later Royal Medico-Psychological Association) produced the seventh edition of their manual "For the Attendants on the Insane". The new edition was entitled "The Handbook for Mental Nurses". At that time attendants worked 76 hours each week and anyone who wished to study was obliged to attend weekly lectures given by the doctors out of work hours. After study based on "The Red Handbook" attendants were encouraged to take an RMPA examination of 7 or 8 questions, a practical test and an oral exam. At the end of three years and exam results permitting the candidates were awarded an RMPA certificate of competence.[22]

Following World War II the General Nursing Council developed a training course for mental nurses. It was similar to the RMPA course in that it had an exam at the end of the first year and a 'final' exam after three years. The successful candidates became Registered Mental Nurses (RMN). Previous holders of the RMPA qualification were able to transfer to the RMN register. In 1954, when the Old Manor Hospital was amalgamated into the National Health Service it came under the management remit of Knowle Hospital in Fareham, Hampshire. The training of nurses from the Old Manor was transferred to Knowle Hospital. The initial 12 weeks of training was a residential course at Knowle Hospital followed by sessions at the Old Manor under the supervision of tutors. By 1960 the Old Manor had its own education department which administered the whole 3 years training.[22]

In 1974 a reorganisation of the National Health Service placed the Old Manor Hospital within the Salisbury Group of Hospitals within the Salisbury Health District and the nurses' training under the aegis of the Salisbury School of Nursing.[22]

Buildings

Fisherton House Asylum was developed slowly starting with the occupation of Fisherton House and gradually constructing more wards and accommodation as business increased. Some wards were purpose-built but some properties adjacent to the asylum were purchased and incorporated.[3] As more buildings were required property and land on the north side of the Wilton Road was purchased. It is beyond the scope of this article to describe all the buildings constructed – the last ones, mostly prefabricated, were in the 1970s – but the following are some of the more significant buildings, including the known history.

- The architect and date of construction of Finch House(51°04′22″N 1°48′35″W / 51.072778°N 1.809762°W) are unclear. Charles Finch bought it from his uncle William Corbin Finch in 1813 as a "mental institution". At that time it was known as Fisherton Manor. It stood in 4.1 acres with some other buildings. "A country house away from the city".[3] In several places around the site, over doors or on buildings, is William Corbin Finch's monogram. The only one now visible to the public is on the lodge cottage (51°04′23″N 1°48′36″W / 51.073112°N 1.810067°W) at 32 Wilton Road, opposite what was the main entrance to the hospital.

- Pembroke Lodge, situated close to the Wilton Road on the south east corner of the site, built in 1820–30, was originally a private residence. It later became a tavern. It was purchased in 1923 as part of the Fisherton Asylum and was used for ladies who were convalescing.[3] In the late 1950s it became accommodation for male staff and known then as the Male Lodge. From the 1980s it was used as a halfway-house facility to help patients recover their social skills and independence before discharge and was known as Kennet Lodge. It closed in 1997[11] and was purchased and refurbished by the Salisbury Society of Friends as a meeting house.[24] It is a Grade II listed building.[25]

- The Chapel was built by 1862 of redbrick. A simple, single space building with a steep slated roof and a stained glass window on the southern side above the communion table. The chapel contains a wall plaque noting the life of Cecil Chubb. As of 2013 it stands in the centre of the Fountain Way hospital awaiting a decision on its future.[10]

- Llangarren (51°04′25″N 1°48′30″W / 51.073682°N 1.808238°W) Originally this building was two separate residences one facing east, the other west. They formed an architectural unit with the Paragon and were connected by a U-shaped path. When the two parts of the building were combined into a single residence it was named Claylands.[26] It was purchased by the Old Manor Hospital in about 1923 and renamed Llangarren. It was used as a ward for ladies to convalesce. It had large rooms and central heating.[11] It was extended to the east in 1937 to provide extra rooms. It became nurses' accommodation from the 1950s until it closed in the 1990s. It was vandalised and finally seriously damaged by fire in 2008.[27] It was then purchased and developed as a nursing home which opened in 2013.[28]

See also

References

- ↑ Crittal, Elizabeth. "Fisherton Anger". A History of Wiltshire, Vol 6. British History Online. Retrieved 17 July 2013.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 Parry-Jones, William Ll. (1972). The Trade in Lunacy, A Study of Private Madhouses in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul. ISBN 0710070519.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 3.8 3.9 3.10 3.11 3.12 3.13 3.14 3.15 3.16 3.17 Smith, Gertrude. A History of the Old Manor Hospital. Salisbury: Private.

- ↑ Roberts, Andrew. "Summary of the 1828 and 1832 Madhouse Acts". Middlesex University. Retrieved 17 July 2013.

- ↑ "Fisherton Asylum, Nr Salisbury". Salisbury & Winchester Journal. Last chance To Read. 1828. Retrieved 15 July 2013.

- ↑ Soothill, Keith; Rogers, P. Dolan, M. (2008). "A Handbook of Forensic Mental Health". The Development of Secure Psychiatric Facilities. Willan Publishing.

- ↑ "Past Mayors of Salisbury". Salisbury city Council. Retrieved 15 July 2013.

- ↑ "William Corbin Finch". Wikitree. Retrieved 15 July 2013.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 "A Visit to a Convict Lunatic Asylum". From The Cornhill Magazine. The Glasgow Herald. 8 October 1864. Retrieved 15 July 2013.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Pugh, R B; Crittal, Elizabeth. "Public Health and Medical Services". A History of the County of Wiltshire, Vol. 5. British History Online. Retrieved 15 July 2013.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 Percy, Gina; Howe, Tony (2000), A Glimpse into the Past, Salisbury Health Care NHS Trust, p. 18

- ↑ Tantam, Digby (1989). "So you've heard of the Gaskell Medal...". The Psychiatrist. Royal College of Psychiatrists. Retrieved 15 July 2013.

- ↑ Roberts, Andrew. "Index of English and Welsh Lunatic Asylums and Mental Hospitals". Middlesex University. Retrieved 15 July 2013.

- ↑ "Hospital Records Database". St James Hospital, Portsmouth. The National Archives. Retrieved 15 July 2013.

- ↑ "Henry Attfield Tree". Retrieved 15 July 2013.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 "Hughes, Frederic". South Wiltshire Coroner's Inquests. 7 March 1919. Retrieved 18 July 2013.

- ↑ Barham, Peter (2007). "Forgotten Lunatics of The Great War". Down at The Manor. Yale University Press. Retrieved 16 July 2013.

- ↑ "The British Journal of Nursing" (PDF). Royal Commission on Lunacy and Mental Disorder. The British Journal of Nursing. Sep 1926. Retrieved 18 July 2013.

- ↑ Hoskins, John. "Southern Daily Echo". Mental Health Patients kills... Southern Daily Echo. Retrieved 18 July 2013.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 "Old Manor Hospital, Salisbury". Hospital Records Database. The National Archives. Retrieved 19 July 2013.

- ↑ "Old Manor Hosp. (Salisbury) Ltd. (Members Voluntary Winding Up)" (PDF). The London Gazette. 4 May 1954. Retrieved 19 July 2013.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 22.3 22.4 22.5 Stride, Marie (1999). Celebrating Salisbury Nurses. Salisbury Nurses' League. p. 214.

- ↑ Hancock, John (25 May 1978), The Salisbury Journal: 10 Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ "The New Salisbury Quaker Meeting House". Salisbury Quakers. 24 April 2010. Retrieved 18 August 2013.

- ↑ "Nurses Home at Old Manor Hospital". British Listed Buildings. Retrieved 18 August 2013.

- ↑ "Llangarren House, Wilton Road, Salisbury" (PDF). Asset Heritage Consulting. Jan 2011. Retrieved 19 August 2013.

- ↑ Harding, Jill (27 October 2008). "Fire Breaks out on Wilton road". Salisbury Journal.

- ↑ "New Care Home". Gracewell Healthcare. 19 July 2012. Retrieved 19 August 2013.