Old Mandarin

| Old Mandarin | |

|---|---|

| 古官話 / 早期官話 | |

| Region | North China Plain |

| Era | Jin dynasty, Yuan dynasty |

Early forms |

Old Chinese

|

| Chinese characters, 'Phags-pa script | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | – |

| Glottolog | None |

Old Mandarin (Chinese: 古官話; pinyin: Gǔ guānhuà) or Early Mandarin (Chinese: 早期官話; pinyin: zǎoqí guānhuà) was the speech of northern China during the time of the Jin and Yuan dynasties (12th to 14th centuries). New genres of vernacular literature were based on this language, including verse, drama and story forms, such as the qu and sanqu. Its pronunciation has been inferred from the 'Phags-pa script used in the Mongol empire and two rhyme dictionaries, the Menggu Ziyun (1308) and the Zhongyuan Yinyun (1324). The rhyme books differ in some details, but overall show many of the features characteristic of modern Mandarin dialects, such as the reduction and disappearance of final plosives and the reorganization of the Middle Chinese tones.

Name

The name "Mandarin", as a direct translation of the Chinese Guānhuà (官话/官話, "language of the officials"), was initially applied to the lingua franca of the Ming and Qing dynasties, which was based on various northern dialects. It has since been extended to both the modern standard language and northern dialects from the 12th century to the present.[1]

The language was called Hàn'er yányǔ (漢兒言語, "Hàn'er language") or Hànyǔ in the Korean Chinese-language textbook Nogeoldae, after the name Hàn'er or Hànrén used by the Mongols for their northern Chinese subjects, in contrast to Nánrén for southern Chinese.[2]

Sources

China had a strong and conservative tradition of phonological description in the rime dictionaries and their elaboration in rime tables. Thus for example the phonological system of the 11th-century Guangyun was almost identical to that of the Qieyun of more than four centuries earlier, disguising changes in speech over the period. A side-effect of foreign rule of north China between the 10th and 14th centuries was a weakening of many of the old traditions. New genres of vernacular literature such as the qu and sanqu appeared, as well as descriptions of contemporary language that revealed how much the language had changed.[3]

The first alphabetic writing system for Chinese was created by the Tibetan monk 'Phags-pa on the orders of the Mongol emperor Kublai Khan. The 'Phags-pa script, promulgated in 1269, was a vertical adaptation of the Tibetan alphabet, initially aimed at Mongolian, but later adapted to other languages of the empire, including Chinese. It saw limited use until the fall of the Yuan dynasty in 1271.[4] The alphabet shows some influence of traditional phonology, in particular including voiced stops and fricatives that most scholars believe had disappeared from Mandarin dialects by that time.[5] However, so-called entering tone syllables ending in the stops /p/, /t/ or /k/ in Middle Chinese were now all written with a glottal stop ending. The other tones are not marked by the script.

The Menggu Ziyun was a Chinese rhyme dictionary based on 'Phags-pa. The prefaces of the only extant manuscript are dated 1308, but the work is believed to be derived from earlier 'Phags-pa texts. The dictionary is believed to be based on Southern Song rime dictionaries, particularly the Lǐbù yùnlüè (礼部韵略) issued by the Ministry of Rites in 1037. The front matter includes a list of 'Phags-pa letters mapped to the 36 initials of the Song dynasty rhyme table tradition, with further letters for vowels. The entries are grouped into 15 rhyme classes, which correspond closely to the 16 broad rhyme classes of the rhyme tables. Within each rhyme class, entries are grouped by the 'Phags-pa spelling of the final, and then by the four tones of Middle Chinese (not indicated by the 'Phags-pa spelling).[6]

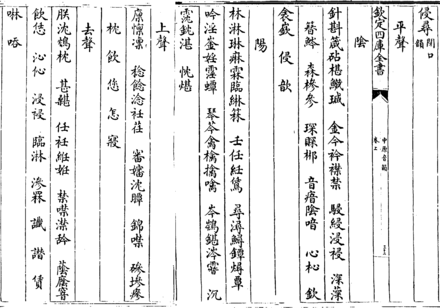

A more radical departure from the rhyme table tradition was the Zhongyuan Yinyun, created by Zhōu Déqīng (周德清) in 1324 as a guide to the rhyming conventions of qu, a new vernacular verse form. The entries are grouped into 19 rhyme classes each identified by a pair of exemplary characters. The rhyme classes are subdivided by tone and then into groups of homophones, with no other indication of pronunciation. The Middle Chinese even tone (平 píng) is divided in upper and lower tones, called 陰平 yīnpíng and 平陽 yángpíng respectively.[7] Syllables in the Middle Chinese entering tone are distributed between the other tones, but placed after the other syllables with labels such as 入聲作去聲 (rùshēng zuò qùshēng "entering tone makes departing tone").

Phonology

The phonology of Old Mandarin is most clearly defined in the Zhongyuan Yinyun. The 'Phags-pa script and the Menggu Ziyun tend to retain more traditional elements, but are useful in filling in the spartan description of the Zhongyuan Yinyun. The language shows many of the features characteristic of modern Mandarin dialects, such as the reduction and disappearance of final stop consonants and the reorganization of the Middle Chinese tones.[5]

In Middle Chinese, initial stops and affricates showed a three-way contrast between voiceless unaspirated, voiceless aspirated and voiced consonants. There were four tones, with the fourth, or "entering tone", comprising syllables ending in stops (-p, -t or -k). Syllables with voiced initials tended to be pronounced with a lower pitch, and by the late Tang dynasty each of the tones had split into two registers conditioned by the initials. When voicing was lost in all dialects except the Wu group, this distinction became phonemic, and the system of initials and tones was re-arranged differently in each of the major groups.[8]

The Zhongyuan Yinyun shows the typical Mandarin four-tone system resulting from a split of the "even" tone and loss of the entering tone. Voiced stops and affricates have become voiceless aspirates in the "even" tone and voiceless non-aspirates in others, a typical feature of modern Mandarin varieties.[7] The distribution of entering tone syllables across syllables with vocalic codas in the other tones differs somewhat from the standard language:[9]

- lower even tone in syllables with voiced obstruent initials,

- rising tone in syllables with voiceless initials, except ʔ, and

- departing tone in syllables with sonorant initials and ʔ.

However such syllables are placed after others of the same tone in the dictionary, perhaps to accommodate Old Mandarin dialects in which former entering tone syllables retained a final glottal stop, as in modern northwestern and southeastern dialects.[10]

| Labials | p- | pʰ- | m- | f- | ʋ- |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dentals | t- | tʰ- | n- | l- | |

| Dental sibilants | ts- | tsʰ- | s- | ||

| Retroflex sibilants | tʂ- | tʂʰ- | ʂ- | r- | |

| Velars | k- | kʰ- | ŋ- | x- | ʜ- |

The initial /ʜ/ denotes a voiced laryngeal onset functioning as a zero initial. It was almost in complementary distribution with the initial /ŋ/, and the two have merged in most modern dialects as a zero initial, [ŋ], [ɣ] or [n].[12] The initial /ʋ/ has also merged with the zero initial and the /w/ medial in the standard language.[13]

The distinction between the dental and retroflex sibilants has persisted in northern Mandarin dialects, including that of Beijing, but the two series have merged in southwestern and southeastern dialects. A more recent development in some dialects (including Beijing) is the merger of palatal allophones of dental sibilants and velars, yielding a palatal series (rendered j-, q- and x- in pinyin).[14]

| Zhongyuan Yinyun rhyme class |

Finals by medial class | Menggu Ziyun rhyme class | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 開口 | 齊齒 | 合口 | 撮口 | ||||

| - | -j- | -w- | -ɥ- | ||||

| 5 | 魚模 yú-mú | -u | -y | 5 | 魚 yú | ||

| 12 | 哥戈 gē-hū | -ɔ | -jɔ[lower-alpha 1] | -wɔ | 14 | 哥 gē | |

| 14 | 車遮 chē-zhē | -jɛ[lower-alpha 2] | -ɥɛ[lower-alpha 2] | 15 | 痲 má | ||

| 13 | 家痲 jiā-má | -a | -ja | -wa | |||

| 3 | 支思 zhī-sī | -ẓ, -ŗ[lower-alpha 3] | 4 | 支 zhī | |||

| 4 | 齊微 qí-wēi | -i | -uj | ||||

| -əj | 6 | 佳 jiā | |||||

| 6 | 皆來 jiē-lái | -aj | -jaj | -waj | |||

| 16 | 尤侯 yóu-hóu | -əw | -iw | 11 | 尤 yóu | ||

| 11 | 蕭豪 xiāo-háo[lower-alpha 4] | -jɛw | -wɔw[lower-alpha 1] | 10 | 蕭 xiāo | ||

| -aw | -jaw | -waw | |||||

| 17 | 侵尋 qīn-xún | -əm | -im | 13 | 侵 qīn | ||

| 19 | 廉纖 lián-xiān | -jɛm | 12 | 覃 tán | |||

| 18 | 監咸 yán-xián | -am | -jam | ||||

| 7 | 真文 zhēn-wén | -ən | -in | -un | -yn | 7 | 真 zhēn |

| 10 | 先天 xiān-tiān | -jɛn | -ɥɛn | 9 | 先 xiān | ||

| 9 | 桓歡 huán-huān | -wɔn | 8 | 寒 hán | |||

| 8 | 寒山 hán-shān | -an | -jan | -wan | |||

| 1 | 東鐘 dōng-zhōng | -uŋ | -juŋ | 1 | 東 dōng | ||

| 15 | 庚青 gēng-qīng | -əŋ | -iŋ | -wəŋ | -yŋ | 2 | 庚 gēng |

| 2 | 江陽 jiāng-yáng | -aŋ | -jaŋ | -waŋ | 3 | 陽 yáng | |

The nasal coda -m merged with -n before the early 17th century, when the late Ming standard was described by European missionaries Matteo Ricci and Nicolas Trigault.[21] However, the language still distinguished mid and open vowels in the pairs -jɛw/-jaw, -jɛn/-jan and -wɔn/-won. For example, 官 and 關, both guān in the modern language, were distinguished as [kwɔn] and [kwan]. These pairs had also merged by the time of Joseph Prémare's 1730 grammar.[22]

Vocabulary

The flourishing vernacular literature of the period also shows distinctively Mandarin vocabulary and syntax, though some, such as the third-person pronoun tā (他), can be traced back to the Tang dynasty.[23]

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 This final occurs in the Zhongyuan Yinyun but not in 'Phags-pa.[16]

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Palatalization was lost after retroflex initials, so -jɛ and -ɥɛ become -ɛ and -wɛ after retroflex initials.[17]

- ↑ ẓ following dental sibilants, ŗ following retroflex sibilants[18]

- ↑ The additional vowels in this rhyme group may reflect contrasts in Zhou Deqing's speech that were no longer distinguished in rhyming practice.[19][20]

References

- ↑ Norman (1988), p. 23, 136.

- ↑ Kaske (2008), p. 46.

- ↑ Norman (1988), pp. 49–50.

- ↑ Coblin (2006), pp. 1–3.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Norman (1988), pp. 51–52.

- ↑ Coblin (2006), pp. 6, 9–15.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Norman (1988), p. 49.

- ↑ Norman (1988), pp. 34–36, 52–54.

- ↑ Pulleyblank (1991), p. 10.

- ↑ Stimson (1977), p. 943.

- ↑ Norman (1988), p. 50, based on Dong (1954); Pulleyblank (1991), pp. 7–8.

- ↑ Pulleyblank (1984), pp. 42, 238.

- ↑ Hsueh (1975), p. 38.

- ↑ Norman (1988), p. 193.

- ↑ Norman (1988), p. 50; Pulleyblank (1971), pp. 143–144; Pulleyblank (1991), pp. 8–9.

- ↑ Pulleyblank (1971), pp. 143–144.

- ↑ Pulleyblank (1991), p. 9.

- ↑ Pulleyblank (1984), p. 237.

- ↑ Hsueh (1975), p. 65.

- ↑ Stimson (1977), p. 942.

- ↑ Coblin (2000), p. 539.

- ↑ Coblin (2000), pp. 538–540.

- ↑ Norman (1988), pp. 111–132.

Works cited

- Coblin, W. South (2000), "A brief history of Mandarin", Journal of the American Oriental Society 120 (4): 537–552, JSTOR 606615.

- —— (2006), A Handbook of 'Phags-pa Chinese, ABC Dictionary Series, Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press, ISBN 978-0-8248-3000-7.

- Hsueh, F. S. (1975), Phonology of Old Mandarin, Mouton De Gruyter, ISBN 978-90-279-3391-1.

- Kaske, Elisabeth (2008), The Politics of Language in Chinese Education, 1895–1919, BRILL, ISBN 978-90-04-16367-6.

- Norman, Jerry (1988), Chinese, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-29653-3.

- Pulleyblank, Edwin George (1971), "Late Middle Chinese, Part II" (PDF), Asia Major 16: 121–166.

- —— (1984), Middle Chinese: a study in historical phonology, Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, ISBN 978-0-7748-0192-8.

- —— (1991), A lexicon of reconstructed pronunciation in Early Middle Chinese, Late Middle Chinese and Early Mandarin, Vancouver: UBC Press, ISBN 978-0-7748-0366-3.

- Stimson, Hugh M. (1977), "Phonology of Old Mandarin by F.S. Hsueh", Language 53 (4): 940–944, JSTOR 412925.

Further reading

- Shen, Zhongwei (2015), "Early Mandarin seen from ancient Altaic scripts", in S-Y. Wang, William; Sun, Chaofen, The Oxford Handbook of Chinese Linguistics, Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 91–103, ISBN 978-0-19-985633-6.

- Stimson, Hugh M. (1966), The Jongyuan In Yunn: a guide to Old Mandarin pronunciation, Far Eastern Publications, Yale University.

External links

- BabelStone: Phags-pa Script, by Andrew West.

- Zhongyuan Yinyun at the Internet Archive: part 1 and part 2.

- Zhongyuan Yinyun, at the Chinese Text Project.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||