Old English

| Old English | |

|---|---|

| Ænglisc, Anglisc, Englisc | |

|

| |

| Region | England (except the extreme south-west and north-west), southern and eastern Scotland, and the eastern fringes of modern Wales. |

| Era | mostly developed into Middle English by the 13th century |

| Dialects |

West Saxon

|

| Runic, later Latin (Old English alphabet). | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-2 |

ang |

| ISO 639-3 |

ang |

| Glottolog |

olde1238[1] |

| Part of a series on |

| Old English |

|---|

|

Dialects |

|

|

Old English (Ænglisc, Anglisc, Englisc) or Anglo-Saxon[2] is the earliest historical form of the English language, spoken in England and southern and eastern Scotland in the early Middle Ages. It was brought to Great Britain by Anglo-Saxon settlers probably in the mid-5th century, and the first Old English literary works date from the mid-7th century. After the Norman conquest of England in 1066, Old English developed into the next historical form of English, known as Middle English.

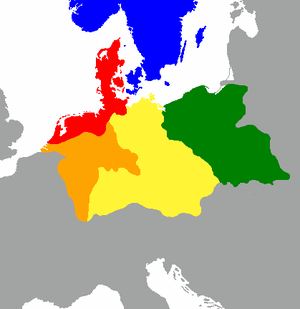

Old English developed from a set of Anglo-Frisian or North Sea Germanic dialects originally spoken along the coasts of Frisia, Lower Saxony, Jutland and Southern Sweden by Germanic tribes traditionally known as the Angles, Saxons, and Jutes. As the Anglo-Saxons became dominant in England, their language replaced the languages of Roman Britain: Common Brittonic, a Celtic language, and Latin, brought to Britain by Roman invasion. Old English had four main dialects (Mercian, Northumbrian, Kentish, and West Saxon), each with distinct differences from the others. After the 9th century, Old English was influenced by Old Norse. The Old English period is arbitrarily considered as ending in 1066, when William the Conqueror conquered England, and Anglo-Norman, a relative of French, replaced English as the language of the upper classes.

Old English is one of the West Germanic languages, and its closest relatives are Old Frisian and Old Saxon. Like other old Germanic languages, it is very different from Modern English and difficult for Modern English speakers to understand without study. Grammatically it is close to Modern Standard German: nouns, adjectives, pronouns, and verbs have many inflectional endings and forms, and word order is much freer. Some Old English inscriptions were written in runes, but literature is written in the Latin alphabet.

History

Old English was not static, and its usage covered a period of 700 years, from the Anglo-Saxon settlement of Britain in the 5th century to the late 11th century, some time after the Norman invasion.

Old English is a West Germanic language, developing out of Ingvaeonic (also known as North Sea Germanic) dialects from the 5th century. Anglo-Saxon literacy developed after Christianisation in the late 7th century. The oldest surviving text of Old English literature is Cædmon's Hymn, composed between 658 and 680. There is a limited corpus of runic inscriptions from the 5th to 7th centuries, but the oldest coherent runic texts (notably Franks Casket) date to the 8th century.

The history of Old English can be subdivided into:

- Prehistoric Old English (c. 450 to 650); for this period, Old English is mostly a reconstructed language as no literary witnesses survive (with the exception of limited epigraphic evidence). This language, or bloc of languages, spoken by the Angles, Saxons, and Jutes, and pre-dating documented Old English or Anglo-Saxon, has also been called Primitive Old English.[3]

- Early Old English (c. 650 to 900), the period of the oldest manuscript traditions, with authors such as Cædmon, Bede, Cynewulf and Aldhelm.

- Late Old English (c. 900 to 1066), the final stage of the language leading up to the Norman conquest of England and the subsequent transition to Early Middle English.

The Old English period is followed by Middle English (12th to 15th century), Early Modern English (c. 1480 to 1650) and finally Modern English (after 1650).

Dialects

Old English should not be regarded as a single monolithic entity just as Modern English is also not monolithic. It emerged over time out of the many dialects and languages of the colonising tribes, and it was not until the later Anglo-Saxon period that they fused together into Old English.[4] Even then, it continued to exhibit local language variation, remnants of which remain in Modern English dialects.[5]

Thus it is misleading, for example, to consider Old English as having a single sound system. Rather, there were multiple Old English sound systems. Old English has variation along regional lines as well as variation across different times.

For example, the language attested in Wessex during the time of Æthelwold of Winchester, which is named Late West Saxon (or Æthelwoldian Saxon), is considerably different from the language attested in Wessex during the time of Alfred the Great's court, which is named Early West Saxon (or Classical West Saxon or Alfredian Saxon). Furthermore, the difference between Early West Saxon and Late West Saxon is of such a nature that Late West Saxon is not directly descended from Early West Saxon (despite what the similarity in name implies).

The four main dialectal forms of Old English were Mercian, Northumbrian, Kentish, and West Saxon.[6] Each of those dialects was associated with an independent kingdom on the island. Of these, Northumbria south of the Tyne and most of Mercia were overrun by the Vikings during the 9th century. The portion of Mercia that was successfully defended and all of Kent were then integrated into Wessex.

After the process of unification of the diverse Anglo-Saxon kingdoms in 878 by Alfred the Great, there is a marked decline in the importance of regional dialects. This is not because they stopped existing, as evidenced both by the existence of Middle and later Modern English dialects.

Hƿæt ƿē Gārde/na ingēar dagum þēod cyninga / þrym ge frunon...

"Listen! We of the Spear-Danes from days of yore have heard of the glory of the folk-kings..."

However, the bulk of the surviving documents from the Anglo-Saxon period are written in the dialect of Wessex, Alfred's kingdom. It seems likely that with consolidation of power, it became necessary to standardise the language of government to reduce the difficulty of administering the more remote areas of the kingdom. As a result, documents were written in the West Saxon dialect. Not only this, but Alfred was passionate about the spread of the vernacular, and brought many scribes to his region from Mercia to record previously unwritten texts.[7]

The Church was affected likewise, especially since Alfred initiated an ambitious programme to translate religious materials into English. To retain his patronage and ensure the widest circulation of the translated materials, the monks and priests engaged in the programme worked in his dialect. Alfred himself seems to have translated books out of Latin and into English, notably Pope Gregory I's treatise on administration, Pastoral Care.

Because of the centralisation of power and the Viking invasions, there is little or no written evidence for the development of non-Wessex dialects after Alfred's unification.

Thomas Spencer Baynes claimed in 1856 that, owing to its position at the heart of the Kingdom of Wessex, the relics of Anglo-Saxon accent, idiom and vocabulary were best preserved in the Somerset dialect.[8]

Even after the maximum Anglo-Saxon expansion, Old English was never spoken all over the Kingdom of England; not only was Medieval Cornish spoken all over Cornwall, it was also spoken in adjacent parts of Devon into the age of the Plantagenets, long after the Norman Conquest. Cumbric may have survived into the 12th century in parts of Cumbria and Welsh may have been spoken on the English side of the Anglo-Welsh border. In addition to the Celtic languages, Norse was spoken in some areas under Danish law.

Phonology

The inventory of classical Old English (i.e. Late West Saxon) surface phones, as usually reconstructed, is as follows.

| Labial | Dental | Alveolar | Post- alveolar |

Palatal | Velar | Glottal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | (n̥) n | (ŋ) | ||||

| Stop | p b | t d | k ɡ | ||||

| Affricate | tʃ (dʒ) | ||||||

| Fricative | f (v) | θ (ð) | s (z) | ʃ | (ç) | (x ɣ) | h |

| Approximant | (l̥) l | j | (ʍ) w | ||||

| Trill | (r̥) r |

The sounds marked in parentheses in the chart above are allophones:

- [dʒ] is an allophone of /j/ occurring after /n/ and when geminated

- [ŋ] is an allophone of /n/ occurring before /k/ and /ɡ/

- [v, ð, z] are allophones of /f, θ, s/ respectively, occurring between vowels or voiced consonants

- [ç, x] are allophones of /h/ occurring in coda position after front and back vowels respectively

- [ɣ] is an allophone of /ɡ/ occurring after a vowel, and, at an earlier stage of the language, in the syllable onset.

| Front | Back | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| unrounded | rounded | unrounded | rounded | |

| Close | i iː | y yː | u uː | |

| Mid | e eː | (ø øː) | o oː | |

| Open | æ æː | ɑ ɑː | ||

The front mid rounded vowels /ø(ː)/ occur in some dialects of Old English, but not in the best attested Late West Saxon dialect.

| First element |

Short (monomoraic) |

Long (bimoraic) |

|---|---|---|

| High | iy/ie | iːy/iːe |

| Mid | eo | eːo |

| Low | æɑ | æːɑ |

Vowels were not the only letters and sounds different from Modern English. In Old English, c always sounded like the modern k, never that of s. G sounded like the y in yes when it was before or after a palatal vowel or any diphthong, but it sounded approximately like the g in go when it was before or after a guttural vowel or a mixed vowel.[9]

Letters that are present in Modern English but are completely absent from Old English include j, q, v, and z. The letter k was used, but only rarely.[10]

Sound changes

The following table shows a possible sequence of changes for some basic vocabulary items, leading from Proto-Indo-European (PIE) to Modern English. The notation >! indicates an unexpected change (the simple notation ">" indicates an expected change). An empty cell means no change at the given stage for the given item. Only sound changes that had an effect on one or more of the vocabulary items are shown.

| one | two | three | four | five | six | seven | mother | heart | hear | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proto-Indo-European | óynos | dúoH | tríh₂ (fem.) | kʷetwṓr | pénkʷe | séḱs | septḿ̥ | méh₂tēr | ḱḗr | h₂ḱowsyónom |

| Pre-Germanic unexpected changes | >! dwóy | >! tríh₂s | >! petwṓr | >! pémpe | >! sepḿ̥d | >! meh₂tḗr | >! kérdō | |||

| Sonorant epenthesis | sepúmd | |||||||||

| Final overlong vowels | kérdô | |||||||||

| Laryngeal loss | trī́s | mātḗr | kowsyónom | |||||||

| Loss of final nonhigh vowels | pemp | |||||||||

| Grimm's Law | twoi | þrī́s | feþwṓr | fémf | sehs | sefúmt | māþḗr | hértô | housjónom | |

| Verner's Law | oinoz | þrīz | feðwōr | seβumt | māðēr | houzjonom | ||||

| o > a, ō > ā, ô > â | ainaz | twai | feðwār | hertâ | hauzjanam | |||||

| Final -m > -n | hauzjanan | |||||||||

| m > n before dental | seβunt | |||||||||

| Final -n > nasalization | hauzjaną | |||||||||

| Loss of final -t | seβun | |||||||||

| Sievers' Law | hauzijaną | |||||||||

| Nasal raising | fimf | |||||||||

| ā > ō, â > ô | feðwōr | mōðēr | hertô | |||||||

| Proto-Germanic form | ainaz | twai | þrīz | feðwōr | fimf | sehs | seβun | mōðēr | hertô | hauzijaną |

| Final vowel shortening/loss | ainz? | þrīz | feðwur | mōðar | hertō | hauzijan | ||||

| Final -z loss | ain | þrī | ||||||||

| Rhotacism: z > r | haurijan | |||||||||

| Intervocalic ðw > ww | fewwur | |||||||||

| Hardening: ð > d, β > v, f [ɸ] > [f] | finf | sevun | mōdar | |||||||

| Morphological changes | >! þriju | >! herta | ||||||||

| West Germanic pre-form | ain | twai | þriju | fewwur | finf | sehs | sevun | mōdar | herta | haurijan |

| Ingvaeonic (prespirant) nasal loss | fīf | |||||||||

| ai > ā | ān | twā | ||||||||

| Anglo-Frisian brightening | hertæ | hæurijan | ||||||||

| I-mutation | heyrijan | |||||||||

| Loss of medial -ij- | heyran | |||||||||

| Breaking | hĕŭrtæ | |||||||||

| Diphthong height harmony | feowur | hĕŏrtæ | hēran, hiyran | |||||||

| Back mutation | sĕŏvun | |||||||||

| Final reduction | feowor | sĕŏvon | >! mōdor | hĕŏrte | ||||||

| Raising: ehs eht > ihs iht | sihs | |||||||||

| hs > ks | siks | |||||||||

| Late OE lowering: iu > eo | þreo | |||||||||

| iy > ȳ | hȳran | |||||||||

| Late Old English spelling | ān | twā | þrēo | fēowor | fīf | six | seofon | mōdor | heorte | hēran, hȳran |

| Middle English (ME) smoothing | θrøː | føːwor | søvon | hørte | ||||||

| ME final reduction | føːwǝr | søvǝn | moːdǝr | hørtǝ | heːrǝn | |||||

| ME a: æ: > ɔ: ɛ: | ɔːn | twɔː | ||||||||

| -dǝr > -ðǝr | moːðǝr | |||||||||

| ME unexpected (?) vowel changes | >! fiːv-ǝ | >! hɛːrǝn | ||||||||

| ME diphthong changes | >! fowǝr | |||||||||

| Late ME unrounding | θreː | sevǝn | hertǝ | |||||||

| Late Middle English spelling (c. 1350) | oon | two | three | fower | five | six | seven | mother | herte | heere(n) |

| Late ME final reduction (late 1300's) | >! fowr | fiːv | hert | hɛːr | ||||||

| Late ME /er/ > /ar/ (1400's)[11] | hart | |||||||||

| Late ME Great Vowel Shift (c. 1400-1550) | oːn >! wʊn | twoː | θriː | fǝiv | muːðǝr | heːr | ||||

| Early Modern English (EModE) smoothing | foːr | |||||||||

| EModE raising /woː/ > /wuː/ > /uː/[12] | tuː | |||||||||

| EModE shortening | mʊðǝr | |||||||||

| EModE /ʊ/ > /ʌ/ | wʌn | mʌðǝr | ||||||||

| Later vowel shifts | fɔːr | faiv | sɪks | hɑrt | hiːr | |||||

| Loss of -r (regional) | fɔː | mʌðǝ | hɑːt | hiǝ | ||||||

| Modern pronunciation | wʌn | tuː | θriː | fɔː(r) | faiv | sɪks | sevǝn | mʌðǝ(r) | hɑrt/hɑːt | hiːr/hiǝ |

| one | two | three | four | five | six | seven | mother | heart | hear |

NOTE: Some of the changes listed above as "unexpected" are more predictable than others. For example:

- Some changes are morphological ones that move a word from a rare declension to a more common one, and hence are not so surprising: e.g. *þrī "three" >! *þriu (adding the common West Germanic feminine ending -u) and *keːr "heart" (stem *kerd-) >! *kérd-oː (change from consonant stem to n-stem).

- Some changes are assimilations that are unexpected but of a cross-linguistically common type, e.g. føːwǝr "four" >! fowǝr where **fewǝr would be expected by normal sound change. Assimilations involving adjacent numbers are especially common, e.g. *kʷetwṓr "four" >! *petwṓr by assimilation to *pénkʷe "five" (in addition, /kʷ/ > /p/ is a cross-linguistically common sound change in general).

- On the other extreme, the Early Modern English change of oːn "one" >! wʊn is almost completely mysterious. Note that the related words alone ( < all + one) and only ( < one + -ly) did not change.

The sound change in "one" is, however, somewhat reminiscent of other cases of "smearing" or breaking of short o, as in Spanish fuerte, puerto, (originally forte, porto, as in Italian), as well as in Kashubian, where the letter ò also represents /wɛ/.

Grammar

Morphology

Unlike Modern English, Old English is a language rich with morphological diversity. It maintains several distinct cases: the nominative, accusative, genitive, dative and (vestigially) instrumental. The only remnants of this system in Modern English are in a few pronouns (the meanings of I (nominative) my (genitive) and me (accusative/dative) in the first person provide an example) and in the possessive ending "-'s", which derives from the genitive ending "-es".

Old English nouns had grammatical gender which is a feature absent in modern English which uses natural gender. For example, sēo sunne (the Sun) was feminine, se mōna (the Moon) was masculine, and þæt wīf "the woman/wife" was neuter. Pronominal usage could reflect either natural or grammatical gender, when those conflicted.

The verb identifies person, number, tense, and mood. Verbs have three moods (Indicative, Subjunctive, and Imperative). They have two numbers (Singular and Plural), three genders (Masculine, Feminine, and Neuter), and only two synthetic tenses (simple present and simple past). Old English grammar also does not contain a synthetic passive.[13] However, Old English does occasionally use compound constructions to express other verbal aspects, the future and the passive voice; in these we see the beginnings of the compound tenses of Modern English.[14]

Old English verbs are separated into two categories according to how they form tenses. Strong verbs change tense by altering the root vowel (like irregular verbs in Modern English) and weak verbs change tense by adding a suffix to the end of the verb (like the –ed or -s in regular verbs in Modern English).[13] Throughout time, however, most of the strong verbs of Old English had either shifted into regular verbs in Modern English or disappeared from the English language altogether. According to linguist Edward Finegan, the number of strong verbs in English has dropped from 333, including "burn" and "help", to 68 irregular verbs today, though conversely, there are also a few weak verbs that have shifted into irregular form, such as "dive" and "wear", and there are also some verbs which have debatable regularity status, such as "sneaked" and "snuck" for "sneak".[15] In comparison to Modern English, Old English had far more irregularity in verb conjugation.

Syntax

Old English syntax was similar in many ways to that of modern English. However, there were some important differences. Some were simply consequences of the greater level of nominal and verbal inflection – e.g., word order was generally freer. In addition:

- The default word order was verb-second and more like modern German than modern English.

- There was no do-support in questions and negatives.

- Multiple negatives could stack up in a sentence, and intensified each other (negative concord), which is not always the case in modern English.

- Sentences with subordinate clauses of the type "when X, Y" (e.g. "When I got home, I ate dinner") did not use a wh-type conjunction, but rather used a th-type correlative conjunction (e.g. þā X, þā Y in place of "when X, Y"). The wh-type conjunctions were used only as interrogative pronouns and indefinite pronouns.

- Similarly, wh- forms were not used as relative pronouns (as in "the man who saw me" or "the car that I bought"). Instead, an indeclinable word þe was used, often in conjunction with the definite article (which was declined for case, number and gender).

Orthography

Old English was first written in runes (futhorc) but shifted to a (minuscule) half-uncial script of the Latin alphabet introduced by Irish Christian missionaries[16] from around the 9th century. This was replaced by insular script, a cursive and pointed version of the half-uncial script. This was used until the end of the 12th century when continental Carolingian minuscule (also known as Caroline) replaced the insular.

The letter ðæt ⟨ð⟩ (called eth or edh in modern English) was an alteration of Latin ⟨d⟩, and the runic letters thorn ⟨þ⟩ and wynn ⟨ƿ⟩ are borrowings from futhorc. Also used was a symbol for the conjunction and, a character similar to the number seven (⟨⁊⟩, called a Tironian note), and a symbol for the relative pronoun þæt, a thorn with a crossbar through the ascender (⟨ꝥ⟩). Macrons ⟨¯⟩ over vowels were rarely used to indicate long vowels. Also used occasionally were abbreviations for a following m or n. All of the sound descriptions below are given using IPA symbols.

Conventions of modern editions

A number of changes are traditionally made in published modern editions of the original Old English manuscripts. Some of these conventions include the introduction of punctuation and the substitutions of symbols. The symbols ⟨e⟩, ⟨f⟩, ⟨g⟩, ⟨r⟩, ⟨s⟩ are used in modern editions, although their shapes in the insular script are considerably different. The long s ⟨ſ⟩ is substituted by its modern counterpart ⟨s⟩. Insular ⟨ᵹ⟩ is usually substituted with its modern counterpart ⟨g⟩ (which is ultimately a Carolingian symbol).

Additionally, modern editions often distinguish between a velar and palatal ⟨c⟩ and ⟨g⟩ with diacritic dots above the putative palatals: ⟨ċ⟩, ⟨ġ⟩. The wynn symbol ⟨ƿ⟩ is usually replaced with ⟨w⟩. Macrons are usually found in modern editions to indicate putative long vowels, while they are usually lacking in the originals. In older printed editions of Old English works, an acute accent mark was used to maintain cohesion between Old English and Old Norse printing.

The alphabetical symbols found in Old English writings and their substitute symbols found in modern editions are listed below:

| Symbol | Description and notes |

|---|---|

| a | Short /ɑ/. Spelling variations like ⟨land⟩ ~ ⟨lond⟩ "land" suggest it may have had a rounded allophone [ɒ] before [n] in some cases |

| ā | Long /ɑː/. Rarely found in manuscripts, but usually distinguished from short ⟨a⟩ in modern editions. |

| æ | Short /æ/. Before 800 the digraph ⟨ae⟩ is often found instead of ⟨æ⟩. During the 8th century ⟨æ⟩ began to be used more frequently. It was standard after 800. In 9th-century Kentish manuscripts, a form of ⟨æ⟩ that was missing the upper hook of the ⟨a⟩ part was used. Kentish ⟨æ⟩ may be either /æ/ or /e/ although this is difficult to determine. |

| ǣ | Long /æː/. Rarely found in manuscripts, but usually distinguished from short ⟨æ⟩ in modern editions. |

| b | Represented /b/. Also represented [v] in early texts before 800. For example, the word "sheaves" is spelled ⟨scēabas⟩ in an early text but later (and more commonly) as ⟨scēafas⟩. |

| c | Except in the digraphs ⟨sc⟩, ⟨cg⟩, either /tʃ/ or /k/. The /tʃ/ pronunciation is sometimes written with a diacritic by modern editors: most commonly ⟨ċ⟩, sometimes ⟨č⟩ or ⟨ç⟩. Before a consonant letter the pronunciation is always /k/; word-finally after ⟨i⟩ it is always /tʃ/. Otherwise, a knowledge of the historical linguistics of the word is needed to predict which pronunciation is needed. (For details, see Phonological history of Old English § Palatalization.) |

| cg | [ddʒ] (the surface pronunciation of geminate /jj/); occasionally also for /ɡɡ/ |

| d | Represented /d/. In the earliest texts, it also represented /θ/ but was soon replaced by ⟨ð⟩ and ⟨þ⟩. For example, the word meaning "thought" (lit. mood-i-think, with -i- as in "handiwork") was written ⟨mōdgidanc⟩ in a Northumbrian text dated 737, but later as ⟨mōdgeþanc⟩ in a 10th-century West Saxon text. |

| ð | Represented /θ/ and its allophone [ð]. Called ðæt in Old English (now called eth in Modern English), ⟨ð⟩ is found in alternation with thorn ⟨þ⟩ (both representing the same sound) although it is more common in texts dating before Alfred. Together with ⟨þ⟩ it replaced earlier ⟨d⟩ and ⟨th⟩. First attested (in definitely dated materials) in the 7th century. After the beginning of Alfred's time, ⟨ð⟩ was used more frequently for medial and final positions while ⟨þ⟩ became increasingly used in initial positions, although both still varied. Some modern editions attempt to regularise the variation between ⟨þ⟩ and ⟨ð⟩ by using only ⟨þ⟩.[17] |

| e | Short /e/. |

| ę | Either Kentish /æ/ or /e/ although this is difficult to determine. A modern editorial substitution for a form of ⟨æ⟩ missing the upper hook of the ⟨a⟩ found in 9th-century texts. (See also: e caudata) |

| ē | Long /eː/. Rarely found in manuscripts, but usually distinguished from short ⟨e⟩ in modern editions. |

| ea | Short /æɑ/; after ⟨ċ⟩, ⟨ġ⟩, sometimes /æ/ or /ɑ/. |

| ēa | Long /æːɑ/. Rarely found in manuscripts, but usually distinguished from short ⟨ea⟩ in modern editions. After ⟨ċ⟩, ⟨ġ⟩, sometimes /æː/. |

| eo | Short /eo/; after ⟨ċ⟩, ⟨ġ⟩, sometimes /o/ |

| ēo | Long /eːo/. Rarely found in manuscripts, but usually distinguished from short ⟨eo⟩ in modern editions. |

| f | /f/ and its allophone [v] |

| g | /ɡ/ and its allophone [ɣ]; /j/ and its allophone [dʒ] (when after ⟨n⟩). In Old English manuscripts, this letter usually took its insular form ⟨ᵹ⟩. The /j/ and [dʒ] pronunciations are sometimes written ⟨ġ⟩ by modern editors. Before a consonant letter the pronunciation is always [ɡ] (word-initially) or [ɣ] (after a vowel). Word-finally after ⟨i⟩ it is always /j/. Otherwise a knowledge of the historical linguistics of the word in question is needed to predict which pronunciation is needed. (For details, see Phonological history of Old English § Palatalization.) |

| h | /h/ and its allophones [ç, x]. In the combinations ⟨hl⟩, ⟨hr⟩, ⟨hn⟩, ⟨hw⟩, the second consonant was certainly voiceless. |

| i | Short /i/. |

| ī | Long /iː/. Rarely found in manuscripts, but usually distinguished from short ⟨i⟩ in modern editions. |

| ie | Short /iy/; after ⟨ċ⟩, ⟨ġ⟩, sometimes /e/. |

| īe | Long /iːy/. Rarely found in manuscripts, but usually distinguished from short ⟨ie⟩ in modern editions. After ⟨ċ⟩, ⟨ġ⟩, sometimes /eː/. |

| k | /k/ (rarely used) |

| l | /l/; probably velarised (as in Modern English) when in coda position. |

| m | /m/ |

| n | /n/ and its allophone [ŋ] |

| o | Short /o/. |

| ō | Long /oː/. Rarely found in manuscripts, but usually distinguished from short ⟨o⟩ in modern editions. |

| oe | Short /ø/ (in dialects with this sound). |

| ōe | Long /øː/ (in dialects with this sound). Rarely found in manuscripts, but usually distinguished from short ⟨oe⟩ in modern editions. |

| p | /p/ |

| qu | A rare spelling of /kw/, which was usually written as ⟨cƿ⟩ (= ⟨cw⟩ in modern editions).[18] |

| r | /r/; the exact nature of /r/ is not known. It may have been an alveolar approximant [ɹ] as in most modern accents, an alveolar flap [ɾ], or an alveolar trill [r]. |

| s | /s/ and its allophone [z]. |

| sc | /ʃ/ or occasionally /sk/. |

| t | /t/ |

| th | Represented /θ/ in the earliest texts but was soon replaced by ⟨ð⟩ and ⟨þ⟩. For example, the word meaning "thought" was written ⟨mōdgithanc⟩ in an 8th-century Northumbrian text, but later as ⟨mōdgeþanc⟩ in a 10th-century West Saxon text. |

| þ | An alternative symbol called thorn used instead of ⟨ð⟩. Represents /θ/ and its allophone [ð]. Together with ⟨ð⟩ it replaced the earlier ⟨d⟩ and ⟨th⟩. First attested (in definitely dated materials) in the 8th century. Less common than ⟨ð⟩ before Alfred's time, from then onward ⟨þ⟩ was used increasingly more frequently than ⟨ð⟩ at the beginning of words while its occurrence at the end and in the middle of words was rare. Some modern editions attempt to regularise the variation between ⟨þ⟩ and ⟨ð⟩ by using only ⟨þ⟩. |

| u | /u/ and /w/ in early texts of continental scribes. The /w/ ⟨u⟩ was eventually replaced by ⟨ƿ⟩ outside of the north of the island. |

| uu | /w/ in early texts of continental scribes. Outside of the north, it was generally replaced by ⟨ƿ⟩. |

| ū | Long /uː/. Rarely found in manuscripts, but usually distinguished from short ⟨u⟩ in modern editions. |

| w | /w/. A modern substitution for ⟨ƿ⟩. |

| ƿ | Runic wynn. Represents /w/, replaced in modern print by ⟨w⟩ to prevent confusion with ⟨p⟩. |

| x | /ks/ (but according to some authors, [xs ~ çs]) |

| y | Short /y/. |

| ȳ | Long /yː/. Rarely found in manuscripts, but usually distinguished from short ⟨y⟩ in modern editions. |

| z | /ts/. A rare spelling for ⟨ts⟩. Example: /betst/ "best" is rarely spelled ⟨bezt⟩ for more common ⟨betst⟩. |

Doubled consonants are geminated; the geminate fricatives ⟨ðð⟩/⟨þþ⟩, ⟨ff⟩ and ⟨ss⟩ cannot be voiced.

Influence of other languages

In the course of the Early Middle Ages, Old English assimilated some aspects of a few languages with which it came in contact, such as the two dialects of Old Norse from the contact with the Norsemen or "Danes" who by the late 9th century controlled large tracts of land in northern and eastern England, which came to be known as the Danelaw.

Latin influence

A large percentage of the educated and literate population of the time were competent in Latin, which was the scholarly and diplomatic lingua franca of Western Europe. It is sometimes possible to give approximate dates for the entry of individual Latin words into Old English based on which patterns of linguistic change they have undergone. There were at least three notable periods of Latin influence. The first occurred before the ancestral Angles and Saxons left continental Europe for Britain. The second began when the Anglo-Saxons were converted to Christianity and Latin-speaking priests became widespread. See Latin influence in English: Early Middle Ages for details.

The third and largest single transfer of Latin-based words happened after the Norman Conquest of 1066, when an enormous number of Norman (Old French) words began to influence the language. Most of these Oïl language words were themselves derived from Old French and ultimately from classical Latin, although a notable stock of Norse words were introduced or re-introduced in Norman form. The Norman Conquest approximately marks the end of Old English and the advent of Middle English.

One of the ways the influence of Latin can be seen is that many Latin words for activities also came to be used to refer to the people engaged in those activities, an idiom carried over from Anglo-Saxon but using Latin words. This can be seen in words like militia, assembly, movement, and service.

The language was further altered by the transition away from the runic alphabet (also known as futhorc or fuþorc) to the Latin alphabet, which was also a significant factor in the developmental pressures brought to bear on the language. Old English words were spelled, more or less, as they were pronounced. Often, the Latin alphabet fell short of being able to adequately represent Anglo-Saxon phonetics. Spellings, therefore, can be thought of as best-attempt approximations of how the language actually sounded.

The "silent" letters in many Modern English words were pronounced in Old English: for example, the c and h in cniht, the Old English ancestor of the modern knight, were pronounced. Another side-effect of spelling Old English words phonetically using the Latin alphabet was that spelling was extremely variable. A word's spelling could also reflect differences in the phonetics of the writer's regional dialect. Words also endured idiosyncratic spelling choices of individual authors, some of whom varied spellings between works. Thus, for example, the word and could be spelt either and or ond.

Norse influence

The second major source of loanwords to Old English were the Scandinavian words introduced during the Viking invasions of the 9th and 10th centuries. In addition to a great many place names, these consist mainly of items of basic vocabulary, and words concerned with particular administrative aspects of the Danelaw (that is, the area of land under Viking control, which included extensive holdings all along the eastern coast of England and Scotland).

The Vikings spoke Old Norse, a language related to Old English in that both derived from the same ancestral Proto-Germanic language. It is very common for the intermixing of speakers of different dialects, such as those that occur during times of political unrest, to result in a mixed language, and one theory holds that exactly such a mixture of Old Norse and Old English helped accelerate the decline of case endings in Old English.[19]

Apparent confirmation of this is the fact that simplification of the case endings occurred earliest in the north and latest in the south-west, the area farthest away from Viking influence. Regardless of the truth of this theory, the influence of Old Norse on the lexicon of the English language has been profound: responsible for such basic vocabulary items as sky, leg, the pronoun they, the verb form are, and hundreds of other words.[20]

Celtic influence

Traditionally, and following the Anglo-Saxon preference prevalent in the 19th century, many maintain that the influence of Brythonic Celtic on English has been small, citing the small number of Celtic loanwords taken into the language. The number of Celtic loanwords is of a lower order than either Latin or Scandinavian. However, a more recent and still minority view is that distinctive Celtic traits can be discerned in syntax from the post-Old English period, such as the regular progressive construction and analytic word order in opposition to the Germanic languages.[21]

Literature

Old English literature, though more abundant than literature of the continent before AD 1000 is nonetheless scant. In his supplementary article to the 1935 posthumous edition of Bright's Anglo-Saxon Reader, Dr. James Hulbert writes:

In such historical conditions, an incalculable amount of the writings of the Anglo-Saxon period perished. What they contained, how important they were for an understanding of literature before the Conquest, we have no means of knowing: the scant catalogues of monastic libraries do not help us, and there are no references in extant works to other compositions....How incomplete our materials are can be illustrated by the well-known fact that, with few and relatively unimportant exceptions, all extant Anglo-Saxon poetry is preserved in four manuscripts.

Some of the most important surviving works of Old English literature are Beowulf, an epic poem; the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, a record of early English history; the Franks Casket, an inscribed early whalebone artefact; and Cædmon's Hymn, a Christian religious poem. There are also a number of extant prose works, such as sermons and saints' lives, biblical translations, and translated Latin works of the early Church Fathers, legal documents, such as laws and wills, and practical works on grammar, medicine, and geography. Still, poetry is considered the heart of Old English literature. Nearly all Anglo-Saxon authors are anonymous, with a few exceptions, such as Bede and Cædmon.

Beowulf

The first example is taken from the opening lines of the epic poem Beowulf. This passage describes how Hrothgar's legendary ancestor Scyld was found as a baby, washed ashore, and adopted by a noble family. The translation is literal and represents the original poetic word order. As such, it is not typical of Old English prose. The modern cognates of original words have been used whenever practical to give a close approximation of the feel of the original poem.

The words in brackets are implied in the Old English by noun case and the bold words in brackets are explanations of words that have slightly different meanings in a modern context. Notice how what is used by the poet where a word like lo or behold would be expected. This usage is similar to what-ho!, both an expression of surprise and a call to attention.

English poetry is based on stress and alliteration. In alliteration, the first consonant in a word alliterates with the same consonant at the beginning of another word, as with Gār-Dena and ġeār-dagum. Vowels alliterate with any other vowel, as with æþelingas and ellen. In the text below, the letters that alliterate are bolded.

| Original | Translation | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Hwæt! wē Gār-Dena in ġeār-dagum, | What! We of Gare-Danes (lit. Spear-Danes) in yore-days, |

| þēod-cyninga, þrym ġefrūnon, | of thede(nation/people)-kings, did thrum (glory) frayne (learn about by asking), | |

| hū ðā æþelingas ellen fremedon. | how those athelings (noblemen) did ellen (fortitude/courage/zeal) freme (promote). | |

| Oft Scyld Scēfing sceaþena þrēatum, | Oft did Scyld Scefing of scather threats (troops), | |

| 5 | monegum mǣġþum, meodosetla oftēah, | of many maegths (clans; cf. Irish cognate Mac-), of mead-settees atee (deprive), |

| egsode eorlas. Syððan ǣrest wearð | [and] ugg (induce loathing in, terrify; related to "ugly") earls. Sith (since, as of when) erst (first) [he] worthed (became) | |

| fēasceaft funden, hē þæs frōfre ġebād, | [in] fewship (destitute) found, he of this frover (comfort) abode, | |

| wēox under wolcnum, weorðmyndum þāh, | [and] waxed under welkin (firmament/clouds), [and amid] worthmint (honour/worship) threed (throve/prospered) | |

| oðþæt him ǣġhwylc þāra ymbsittendra | oth that (until that) him each of those umsitters (those "sitting" or dwelling roundabout) | |

| 10 | ofer hronrāde hȳran scolde, | over whale-road (kenning for "sea") hear should, |

| gomban gyldan. Þæt wæs gōd cyning! | [and] yeme (heed/obedience; related to "gormless") yield. That was [a] good king! |

A semi-fluent translation in Modern English would be:

Lo! We have heard of majesty of the Spear-Danes, of those nation-kings in the days of yore, and how those noblemen promoted zeal. Scyld Scefing took away mead-benches from bands of enemies, from many tribes; he terrified earls. Since he was first found destitute (he gained consolation for that) he grew under the heavens, prospered in honours, until each of those who lived around him over the sea had to obey him, give him tribute. That was a good king!

The Lord's Prayer

This text of the Lord's Prayer is presented in the standardised West Saxon literary dialect, with added macrons for vowel length, markings for probable palatalised consonants, modern punctuation, and the replacement of the letter wynn with w.

| Line | Original | Translation |

|---|---|---|

| [1] | Fæder ūre þū þe eart on heofonum, | Father of ours, thou who art in heavens, |

| [2] | Sī þīn nama ġehālgod. | Be thy name hallowed. |

| [3] | Tōbecume þīn rīċe, | Come thy riche (kingdom), |

| [4] | ġewurþe þīn willa, on eorðan swā swā on heofonum. | Worth (manifest) thy will, on earth as also in heaven. |

| [5] | Ūre ġedæġhwāmlīcan hlāf syle ūs tō dæġ, | Our daily loaf do sell (give) to us today, |

| [6] | and forġyf ūs ūre gyltas, swā swā wē forġyfað ūrum gyltendum. | And forgive us our guilts as also we forgive our guilters[22] |

| [7] | And ne ġelǣd þū ūs on costnunge, ac ālȳs ūs of yfele. | And do not lead thou us into temptation, but alese (release/deliver) us of (from) evil. |

| [8] | Sōþlīċe. | Soothly. |

Charter of Cnut

This is a proclamation from King Cnut the Great to his earl Thorkell the Tall and the English people written in AD 1020. Unlike the previous two examples, this text is prose rather than poetry. For ease of reading, the passage has been divided into sentences while the pilcrows represent the original division.

| Original | Translation |

|---|---|

| ¶ Cnut cyning gret his arcebiscopas and his leod-biscopas and Þurcyl eorl and ealle his eorlas and ealne his þeodscype, twelfhynde and twyhynde, gehadode and læwede, on Englalande freondlice. | ¶ Cnut, king, greets his archbishops and his lede'(people's)'-bishops and Thorkell, earl, and all his earls and all his peopleship, greater (having a 1200 shilling weregild) and lesser (200 shilling weregild), hooded(ordained to priesthood) and lewd(lay), in England friendly. |

| And ic cyðe eow, þæt ic wylle beon hold hlaford and unswicende to godes gerihtum and to rihtre woroldlage. | And I kithe(make known/couth to) you, that I will be [a] hold(civilised) lord and unswiking(uncheating) to God's rights(laws) and to [the] rights(laws) worldly. |

| ¶ Ic nam me to gemynde þa gewritu and þa word, þe se arcebiscop Lyfing me fram þam papan brohte of Rome, þæt ic scolde æghwær godes lof upp aræran and unriht alecgan and full frið wyrcean be ðære mihte, þe me god syllan wolde. | ¶ I nam(took) me to mind the writs and the word that the Archbishop Lyfing me from the Pope brought of Rome, that I should ayewhere(everywhere) God's love(praise) uprear(promote), and unright(outlaw) lies, and full frith(peace) work(bring about) by the might that me God would(wished) [to] sell'(give). |

| ¶ Nu ne wandode ic na minum sceattum, þa hwile þe eow unfrið on handa stod: nu ic mid godes fultume þæt totwæmde mid minum scattum. | ¶ Now, ne went(withdrew/changed) I not my shot(financial contribution, cf. Norse cognate in scot-free) the while that you stood(endured) unfrith(turmoil) on-hand: now I, mid(with) God's support, that [unfrith] totwemed(separated/dispelled) mid(with) my shot(financial contribution). |

| Þa cydde man me, þæt us mara hearm to fundode, þonne us wel licode: and þa for ic me sylf mid þam mannum þe me mid foron into Denmearcon, þe eow mæst hearm of com: and þæt hæbbe mid godes fultume forene forfangen, þæt eow næfre heonon forð þanon nan unfrið to ne cymð, þa hwile þe ge me rihtlice healdað and min lif byð. | Tho(then) [a] man kithed(made known/couth to) me that us more harm had found(come upon) than us well liked(equalled): and tho(then) fore(travelled) I, meself, mid(with) those men that mid(with) me fore(travelled), into Denmark that [to] you most harm came of(from): and that[harm] have [I], mid(with) God's support, afore(previously) forefangen(forestalled) that to you never henceforth thence none unfrith(breach of peace) ne come the while that ye me rightly hold(behold as king) and my life beeth. |

Old English as a living language

Like other historical languages, Old English has been used by scholars and enthusiasts of later periods to create texts either imitating Anglo-Saxon literature or deliberately transferring it to a different cultural context. Examples include Alistair Campbell and J. R. R. Tolkien. A number of websites devoted to Neo-Paganism and Historical Re-enactment offer reference material and forums promoting the active use of Old English. By far the most ambitious project is the Old English Wikipedia, but most of the Neo-Old English texts published online bear little resemblance to the historical model and are riddled with very basic grammatical mistakes.[23]

See also

- Exeter Book

- Go (verb)

- History of the Scots language

- I-mutation

- Ingvaeonic nasal spirant law Anglo-Frisian nasal spirant law

- List of generic forms in place names in the United Kingdom and Ireland

- List of Germanic and Latinate equivalents in English

Notes

- ↑ Nordhoff, Sebastian; Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2013). "Old English". Glottolog. Leipzig: Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology.

- ↑ The term Anglo-Saxon came to refer to all things of the early English period by the 16th century, including language, culture, and people. While this is still the normal term for the latter two aspects, the language began to be called Old English towards the end of the 19th century, as a result of the increasingly strong anti-Germanic nationalism in English society of the 1890s and early 1900s. The language itself began to be appropriated by some English scholars, who preferentially stressed the development of modern English from the Anglo-Saxon period to Middle English and through to the present day. However many authors still use the term Anglo-Saxon to refer to the language.

Crystal, David (2003). The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the English Language. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-53033-4. - ↑ Stumpf, John (1970). An Outline of English Literature; Anglo-Saxon and Middle English Literature. London: Forum House Publishing Company. p. 7.

We do not know what languages the Jutes, Angles, and Saxons spoke, nor even whether they were sufficiently similar to make them mutually intelligible, but it is reasonable to assume that by the end of the sixth century there must have been a language that could be understood by all and this we call Primitive Old English.

- ↑ Shore, Thomas William (1906), Origin of the Anglo-Saxon Race – A Study of the Settlement of England and the Tribal Origin of the Old English People (1st ed.), London, pp. 3, 393

- ↑ Origin of the Anglo-Saxon race : a study of the settlement of England and the tribal origin of the Old English people; Author: William Thomas Shore; Editors TW and LE Shore; Publisher: Elliot Stock; published 1906 p. 3

- ↑ Campbell, Alistair (1959). Old English Grammar. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 4. ISBN 0-19-811943-7.

- ↑ Moore, Samuel, and Knott, Thomas A. The Elements of Old English. 1919. Ed. James R. Hulbert. 10th ed. Ann Arbor, Michigan: George Wahr Publishing Co., 1958.

- ↑ The Somersetshire dialect: its pronunciation, 2 papers (1861) Thomas Spencer Baynes, first published 1855 & 1856

- ↑ Anderson, Williams, Marjorie, Blanche (1935). Old English Handbook. Houghton Mifflin Company. pp. 11–12.

- ↑ Anderson, Williams, Marjorie, Blanche (1935). Old English Handbook. Houghton Mifflin. p. 10.

- ↑ Dobson, E.J. (1957), English Pronunciation 1500–1700, London: Oxford University Press, p. 558

- ↑ Dobson, E.J. (1957), English Pronunciation 1500–1700, London: Oxford University Press, pp. 677–678

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 "Continuum Encyclopedia of British Literature". Continuum.

- ↑ Robinson, Fred C (2002). A Guide to Old English. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. pp. 109–12.

- ↑ Finegan, Edward (2012). Language: Its Structure and Use. Boston: Wadsworth, Cengage Learning. p. 488.

- ↑ Crystal, David (1987). The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Language. Cambridge University Press. p. 203. ISBN 0-521-26438-3.

- ↑ See also Pronunciation of English th.

- ↑ The spelling ⟨qu⟩ is much more common in later Middle English.

- ↑ Barber, Charles (2009). The English Language: A Historical Introduction. Cambridge University Press. p. 137. ISBN 978-0-521-67001-2.

- ↑ Scott Shay (30 January 2008). The history of English: a linguistic introduction. Wardja Press. p. 86. ISBN 978-0-615-16817-3. Retrieved 29 January 2012.

- ↑ "Rotary-munich.de" (PDF). Retrieved 20 June 2011.

- ↑ Lit. a participle: "guilting" or "[a person who is] sinning"; cf. Latin cognate -ant/-ent.

- ↑ Christina Neuland and Florian Schleburg. (2014). "A New Old English? The Chances of an Anglo-Saxon Revival on the Internet". In: S. Buschfeld et al. (Eds.), The Evolution of Englishes. The Dynamic Model and Beyond (pp. 486–504). Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Bibliography

Sources

- Whitelock, Dorothy (ed.) (1955) English Historical Documents; vol. I: c. 500–1042. London: Eyre & Spottiswoode

General

- Baker, Peter S. (2003). Introduction to Old English. Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 0-631-23454-3.

- Baugh, Albert C; & Cable, Thomas. (1993). A History of the English Language (4th ed.). London: Routledge.

- Campbell, A. (1959). Old English Grammar. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Earle, John (2005). A Book for the Beginner in Anglo-Saxon. Bristol, PA: Evolution Publishing. ISBN 1-889758-69-8. (Reissue of one of 4 eds. 1877–1902)

- Euler, Wolfram (2013). Das Westgermanische [rest of title missing] (West Germanic: from its Emergence in the 3rd up until its Dissolution in the 7th Century CE: Analyses and Reconstruction). 244 p., in German with English summary, London/Berlin 2013, ISBN 978-3-9812110-7-8.

- Hogg, Richard M. (ed.). (1992). The Cambridge History of the English Language: (Vol 1): the Beginnings to 1066. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Hogg, Richard; & Denison, David (eds.) (2006) A History of the English Language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Jespersen, Otto (1909–1949) A Modern English Grammar on Historical Principles. 7 vols. Heidelberg: C. Winter & Copenhagen: Ejnar Munksgaard

- Lass, Roger (1987) The Shape of English: structure and history. London: J. M. Dent & Sons

- Lass, Roger (1994). Old English: A historical linguistic companion. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-43087-9.

- Millward, Celia (1996). A Biography of the English Language. Harcourt Brace. ISBN 0-15-501645-8.

- Mitchell, Bruce, and Robinson, Fred C. (2001). A Guide to Old English (6th ed.). Oxford: Blackwell. ISBN 0-631-22636-2.

- Quirk, Randolph; & Wrenn, C. L. (1957). An Old English Grammar (2nd ed.) London: Methuen.

- Ringe, Donald R. and Taylor, Ann (2014). The Development of Old English - A Linguistic History of English, vol. II, 632p. ISBN 978-0199207848. Oxford.

- Strang, Barbara M. H. (1970) A History of English. London: Methuen.

External history

- Robinson, Orrin W. (1992). Old English and Its Closest Relatives. Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-2221-8.

- Bremmer Jr, Rolf H. (2009). An Introduction to Old Frisian. History, Grammar, Reader, Glossary. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

- Stenton, F. M. (1971). Anglo-Saxon England (3rd ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Orthography/Palaeography

- Bourcier, Georges. (1978). L'orthographie de l'anglais: Histoire et situation actuelle. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France.

- Elliott, Ralph W. V. (1959). Runes: An introduction. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Keller, Wolfgang. (1906). Angelsächsische Paleographie, I: Einleitung. Berlin: Mayer & Müller.

- Ker, N. R. (1957). A Catalogue of Manuscripts Containing Anglo-Saxon. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Ker, N. R. (1957: 1990). A Catalogue of Manuscripts Containing Anglo-Saxon; with supplement prepared by Neil Ker originally published in Anglo-Saxon England; 5, 1957. Oxford: Clarendon Press ISBN 0-19-811251-3

- Page, R. I. (1973). An Introduction to English Runes. London: Methuen.

- Scragg, Donald G. (1974). A History of English Spelling. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Phonology

- Anderson, John M; & Jones, Charles. (1977). Phonological structure and the history of English. North-Holland linguistics series (No. 33). Amsterdam: North-Holland.

- Brunner, Karl. (1965). Altenglische Grammatik (nach der angelsächsischen Grammatik von Eduard Sievers neubearbeitet) (3rd ed.). Tübingen: Max Niemeyer.

- Campbell, A. (1959). Old English Grammar. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Cercignani, Fausto (1983). "The Development of */k/ and */sk/ in Old English". Journal of English and Germanic Philology, 82 (3): 313–323.

- Girvan, Ritchie. (1931). Angelsaksisch Handboek; E. L. Deuschle (transl.). (Oudgermaansche Handboeken; No. 4). Haarlem: Tjeenk Willink.

- Halle, Morris; & Keyser, Samuel J. (1971). English Stress: its form, its growth, and its role in verse. New York: Harper & Row.

- Hockett, Charles F. (1959). "The stressed syllabics of Old English". Language 35 (4): 575–597. doi:10.2307/410597. JSTOR 410597.

- Hogg, Richard M. (1992). A Grammar of Old English, I: Phonology. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

- Kuhn, Sherman M. (1961). "On the Syllabic Phonemes of Old English". Language 37 (4): 522–538. doi:10.2307/411354. JSTOR 411354.

- Kuhn, Sherman M. (1970). "On the consonantal phonemes of Old English". In: J. L. Rosier (ed.) Philological Essays: studies in Old and Middle English language and literature in honour of Herbert Dean Merritt (pp. 16–49). The Hague: Mouton.

- Lass, Roger; & Anderson, John M. (1975). Old English Phonology. (Cambridge studies in linguistics; No. 14). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Luick, Karl. (1914–1940). Historische Grammatik der englischen Sprache. Stuttgart: Bernhard Tauchnitz.

- Maling, J. (1971). "Sentence stress in Old English". Linguistic Inquiry 2 (3): 379–400. JSTOR 4177642.

- McCully, C. B.; Hogg, Richard M. (1990). "An account of Old English stress". Journal of Linguistics 26 (2): 315–339. doi:10.1017/S0022226700014699.

- Moulton, W. G. (1972). "The Proto-Germanic non-syllabics (consonants)". In: F. van Coetsem & H. L. Kufner (Eds.), Toward a Grammar of Proto-Germanic (pp. 141–173). Tübingen: Max Niemeyer.

- Sievers, Eduard (1893). Altgermanische Metrik. Halle: Max Niemeyer.

- Wagner, Karl Heinz (1969). Generative Grammatical Studies in the Old English language. Heidelberg: Julius Groos.

Morphology

- Brunner, Karl. (1965). Altenglische Grammatik (nach der angelsächsischen Grammatik von Eduard Sievers neubearbeitet) (3rd ed.). Tübingen: Max Niemeyer.

- Campbell, A. (1959). Old English grammar. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Wagner, Karl Heinz. (1969). Generative grammatical studies in the Old English language. Heidelberg: Julius Groos.

Syntax

- Brunner, Karl. (1962). Die englische Sprache: ihre geschichtliche Entwicklung (Vol. II). Tübingen: Max Niemeyer.

- Kemenade, Ans van. (1982). Syntactic Case and Morphological Case in the History of English. Dordrecht: Foris.

- MacLaughlin, John C. (1983). Old English Syntax: a handbook. Tübingen: Max Niemeyer.

- Mitchell, Bruce. (1985). Old English Syntax (Vols. 1–2). Oxford: Clarendon Press (no more published)

- Vol.1: Concord, the parts of speech and the sentence

- Vol.2: Subordination, independent elements, and element order

- Mitchell, Bruce. (1990) A Critical Bibliography of Old English Syntax to the end of 1984, including addenda and corrigenda to "Old English Syntax" . Oxford: Blackwell

- Timofeeva, Olga. (2010) Non-finite Constructions in Old English, with Special Reference to Syntactic Borrowing from Latin, PhD dissertation, Mémoires de la Société Néophilologique de Helsinki, vol. LXXX, Helsinki: Société Néophilologique.

- Traugott, Elizabeth Closs. (1972). A History of English Syntax: a transformational approach to the history of English sentence structure. New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston.

- Visser, F. Th. (1963–1973). An Historical Syntax of the English Language (Vols. 1–3). Leiden: E. J. Brill.

Lexicons

- Bosworth-Toller

- Bosworth, J; & Toller, T. Northcote. (1898). An Anglo-Saxon Dictionary. Oxford: Clarendon Press. (Based on Bosworth's 1838 dictionary, his papers & additions by Toller)

- Toller, T. Northcote. (1921). An Anglo-Saxon Dictionary: Supplement. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Campbell, A. (1972). An Anglo-Saxon Dictionary: Enlarged addenda and corrigenda. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Clark Hall-Merritt

- Clark Hall, J. R; & Merritt, H. D. (1969). A Concise Anglo-Saxon Dictionary (4th ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Toronto

- Cameron, Angus, et al. (ed.) (1983) Dictionary of Old English. Toronto: Published for the Dictionary of Old English Project, Centre for Medieval Studies, University of Toronto by the Pontifical Institute of Medieval Studies, 1983/1994. (Issued on microfiche and subsequently as a CD-ROM and on the World Wide Web.)

External links

| Old English edition of Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia |

| For a list of words relating to Old English, see the Old English language category of words in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Old English. |

- Old English Wikipedia

- Old English/Modern English Translator

- The Electronic Introduction to Old English

- Learn Old English with Leofwin

- Old English (Anglo-Saxon) alphabet

- Bosworth and Toller, An Anglo-Saxon dictionary

- Downloadable Bosworth and Toller, An Anglo-Saxon dictionary Application

- Old English Made Easy

- Old English – Modern English dictionary

- Old English Glossary

- Old English Letters

- Shakespeare's English vs Old English

- Downloadable Old English keyboard for Windows and Mac

- Another downloadable keyboard for Windows computers

- Guide to using Old English computer characters (Unicode, HTML entities, etc.)

- The Germanic Lexicon Project

- An overview of the grammar of Old English

- The Lord's Prayer in Old English from the 11th century (video link)

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||