Okinawan language

| Okinawan | |

|---|---|

| 沖縄口/ウチナーグチ Uchinaaguchi | |

| Pronunciation | [ʔut͡ɕinaːɡut͡ɕi] |

| Native to | Japan |

| Region | Okinawa Islands |

Native speakers | 980,000 (2000)[1] |

| Okinawan, Japanese, Rōmaji | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 |

ryu |

| Glottolog |

cent2126[2] |

| Linguasphere |

45-CAC-ai |

|

(South–Central) Okinawan, AKA Shuri–Naha | |

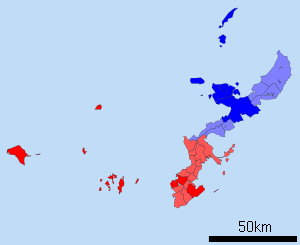

Central Okinawan, or simply the Okinawan language (沖縄口/ウチナーグチ Uchinaaguchi [ʔut͡ɕinaːɡut͡ɕi]), is a Northern Ryukyuan language spoken primarily in the southern half of the island of Okinawa, as well as in the surrounding islands of Kerama, Kumejima, Tonaki, Aguni, and a number of smaller peripheral islands.[4] Central Okinawan distinguishes itself from the speech of Northern Okinawa, which is classified independently as the Kunigami language. Both languages have been designated as endangered by the UNESCO Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger since its launch in February 2009.[5]

Though Okinawan encompasses a number of local dialects,[6] the Shuri-Naha variant is generally recognized as the de facto standard,[7] as it had been used as the official language of the Ryūkyū Kingdom[8] since the reign of King Shō Shin (1477–1526). Moreover, as the former capital of Shuri was built around the royal palace, the language used by the royal court became the regional and literary standard,[8][7] which thus flourished in songs and poems written during that era.

Within Japan, Okinawan is not seen as a language unto itself but is referred to as the Okinawan dialect (沖縄方言 Okinawa hōgen) or more specifically the Central and Southern Okinawan dialects (沖縄中南部諸方言 Okinawa Chūnanbu Sho hōgen).

Okinawan is undergoing language shift as it changes to Japanese. Language use in Okinawa today is far from stable. Okinawan is assimilating to standard Japanese because of the standardized education system, the expanding media, and expanding contact with mainlanders. The process is similar to de-creolization, which is when a creole and the colonizers language are constantly in contact and the creole slowly shifts to be more like the colonizers' language.[9] Okinawan is kept alive in theaters featuring a local drama called uchinaa shibai. These plays depict local customs and manners. [10]

History

Pre-Ryukyu Kingdom

Okinawan is a Japonic language, derived from Old Japanese. The split between Old Japanese and the Ryukyuan languages has been estimated to have occurred as early as the first century AD to as late as the twelfth century AD. Chinese and Japanese characters were first introduced by a Japanese missionary in 1265.[11]

Ryukyu Kingdom Era

- Pre-Satsuma

Hiragana was much more popular than kanji; poems were commonly written solely in hiragana or with little kanji.

- Post-Satsuma to Annexation

After Ryukyu became a vassal of Satsuma Domain, kanji gained more prominence in poetry, however official Ryukyuan documents were written in Classical Chinese.

Japanese Annexation to End of World War II

When Ryukyu was annexed by Japan in 1879, the majority of people on Okinawa Island spoke Okinawan. Within ten years, the Japanese government began an assimilation policy of Japanization, where Ryukyuan languages were gradually suppressed. The education system was the heart of Japanization, where Okinawan children were taught Japanese and punished for speaking their native language, being told that their language was just a "dialect". By 1945, almost all Okinawans spoke Japanese, and many were bilingual. During the Battle of Okinawa, some Okinawans were killed by Japanese soldiers for speaking Okinawan.

American Occupation

Under American administration, there was an attempt to revive and standardize Okinawan, however this proved difficult and was shelved in favor of Japanese. Multiple English words were introduced.

Return to Japan to Present Day

After Okinawa's reversion to Japanese sovereignty, Japanese continued to be the dominant language used, and the majority of the youngest generations only speak Okinawan Japanese. There have been attempts to revive Okinawan by notable people such as Byron Fija and Seijin Noborikawa, however few native Okinawans desire to learn the language.[12]

Phonology

Vowels

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Close | i iː | (ɨ) | u uː |

| Close-Mid | e eː | o oː | |

| Open | a aː |

The Okinawan language has five vowels, all of which may be long or short, though the short vowels /e/ and /o/ are considerably rare[13] as they only occur in a few native Okinawan words, such as /meɴsoːɾeː/ mensooree "welcome" or /toɴɸaː/ tonfaa, and typically only in heavy syllables with the pattern /CeN/ or /CoN/. The close back vowels /u/ and /uː/ are truly rounded, rather than the compressed vowels of standard Japanese. A sixth vowel /ɨ/ is sometimes posited in order to explain why sequences containing a historically raised /e/ fail to trigger palatalization as with /i/: */te/ → /tɨː/ tii "hand", */ti/ → /t͡ɕiː/ chii "blood". Acoustically, however, /ɨ/ is pronounced no differently from /i/, and this distinction can simply be attributed to the fact that palatalization took place prior to this vowel shift.

Consonants

The Okinawan language counts approximately 20 distinctive segments shown in the chart below, with major allophones presented in parentheses.

| Labial | Alveolar | Alveolo- palatal |

Palatal | Labio- velar |

Velar | Glottal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | ɴ (ŋ̍) | ||||

| Plosive | p b | t d | t͡ɕ d͡ʑ | kʷ ɡʷ | k ɡ | ʔ | |

| Fricative | ɸ | s (z) | (ɕ) | (ç) | h | ||

| Flap | ɾ | ||||||

| Approximant | j | w |

The consonant system of the Okinawan language is fairly similar to that of standard Japanese, but it does present a few differences on the phonemic and allophonic level. Namely, Okinawan retains the labialized consonants /kʷ/ and /ɡʷ/ which were lost in Late Middle Japanese, possesses a glottal stop /ʔ/, features a voiceless bilabial fricative /ɸ/ distinct from the aspirate /h/, and has two distinctive affricates which arose from a number of different sound processes. Additionally, Okinawan lacks the major allophones [t͡s] and [d͡z] found in Japanese, having historically fronted the vowel /u/ to /i/ after the alveolars /t d s z/, consequently merging [t͡su] tsu into [t͡ɕi] chi, [su] su into [ɕi] shi, and both [d͡zu] and [zu] into [d͡ʑi]. It also lacks /z/ as a distinctive phoneme, having merged it into /d͡ʑ/.

- Bilabial and glottal fricatives

The bilabial fricative /ɸ/ has sometimes been transcribed as the cluster /hw/, since, like Japanese, /h/ allophonically labializes into [ɸ] before the high vowel /u/, and /ɸ/ does not occur before the rounded vowel /o/. This suggests that an overlap between /ɸ/ and /h/ exists, and so the contrast in front of other vowels can be denoted through labialization. However, this analysis fails to take account of the fact that Okinawan has not fully undergone the diachronic change */p/ → /ɸ/ → */h/ as in Japanese, and that the suggested clusterization and labialization into */hw/ is unmotivated.[14] Consequently, the existence of /ɸ/ must be regarded as independent of /h/, even though the two overlap. Barring a few words that resulted from the former change, the aspirate /h/ also arose from the odd lenition of /k/ and /s/, as well as words loaned from other dialects. Before the glide /j/ and the high vowel /i/, it is pronounced closer to [ç], as in Japanese.

- Palatalization

The plosive consonants /t/ and /k/ historically palatalized and affricated into /t͡ɕ/ before and occasionally following the glide /j/ and the high vowel /i/: */kiri/ → /t͡ɕiɾi/ chiri "fog", and */k(i)jora/ → /t͡ɕuɾa/ chura- "beautiful". This change preceded vowel raising, so that instances where /i/ arose from */e/ did not trigger palatalization: */ke/ → /kiː/ kii "hair". Their voiced counterparts /d/ and /ɡ/ underwent the same effect, becoming /d͡ʑ/ under such conditions: */unaɡi/ → /ʔɴnad͡ʑi/ qnnaji "eel", and */nokoɡiri/ → /nukud͡ʑiɾi/ nukujiri "saw"; but */kaɡeɴ/ → /kaɡiɴ/ kagin "seasoning".

Both /t/ and /d/ may or may not also allophonically affricate before the mid vowel /e/, though this pronunciation is increasingly rare. Similarly, the fricative consonant /s/ palatalizes into [ɕ] before the glide /j/ and the vowel /i/, including when /i/ historically derives from /e/: */sekai/ → [ɕikeː] shikee "world". It may also palatalize before the vowel /e/, especially so in the context of topicalization: [duɕi] dushi → [duɕeː] dusee or dushee "(topic) friend".

In general, sequences containing the palatal consonant /j/ are relatively rare and tend to exhibit depalatalization. For example, /mj/ tends to merge with /n/ ([mjaːku] myaaku → [naːku] naaku "Miyako"); */rj/ has merged into /ɾ/ and /d/ (*/rjuː/ → /ɾuː/ ruu ~ /duː/ duu "dragon"); and /sj/ has mostly become /s/ (/sjui/ shui → /sui/ sui "Shuri").

- Flapping and fortition

The voiced plosive /d/ and the flap /ɾ/ tend to merge, with the first becoming a flap in word-medial position, and the second sometimes becoming a plosive in word-initial position. For example, /ɾuː/ ruu "dragon" may be strengthened into /duː/ duu, and /hasidu/ hashidu "door" conversely flaps into /hasiɾu/ hashiru. The two sounds do, however, still remain distinct in a number of words and verbal constructions.

- Glottal stop

Okinawan also features a distinctive glottal stop /ʔ/ that historically arose from a process of glottalization of word-initial vowels.[15] Hence, all vowels in Okinawan are predictably glottalized at the beginning of words (*/ame/ → /ʔami/ ami "rain"), save for a few exceptions. High vowel loss or assimilation following this process created a contrast with glottalized approximants and nasal consonants.[15] Compare */uwa/ → /ʔwa/ qwa "pig" to /wa/ wa "I", or */ine/ → /ʔɴni/ qnni "rice plant" to */mune/ → /ɴni/ nni "chest".[16]

- Moraic nasal

The moraic nasal /N/ has been posited in most descriptions of Okinawan phonology. Like Japanese, /N/ (transcribed using the small capital /ɴ/) occupies a full mora and its precise place of articulation will vary depending on the following consonant. Before other labial consonants, it will be pronounced closer to a syllabic bilabial nasal [m̩], as in /ʔɴma/ [ʔm̩ma] qmma "horse". Before velar and labiovelar consonants, it will be pronounced as a syllabic velar nasal [ŋ̍], as in /biɴɡata/ [biŋ̍ɡata] bingata, a method of dying clothes. And before alveolar and alveolo-palatal consonants, it becomes a syllabic alveolar nasal /n̩/, as in /kaɴda/ [kan̩da] kanda "vine". Elsewhere, its exact realization remains unspecified, and it may vary depending on the first sound of the next word or morpheme. In isolation and at the end of utterances, it is realized as a velar nasal [ŋ̍].

Correspondences with Japanese

| Japanese | Okinawan | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| /e/ | /iː/[17] | |

| /i/ | ||

| /a/ | /a/[17] | |

| /o/ | /u/[17] | |

| /u/ | ||

| /ai/ | /eː/ | |

| /ae/ | ||

| /au/ | /oː/ | |

| /ao/ | ||

| /aja/ | ||

| /k/ | /k/ | /ɡ/ also occurs |

| /ka/ | /ka/ | /ha/ also occurs |

| /ki/ | /t͡ɕi/ | [t͡ɕi] |

| /ku/ | /ku/ | /hu/, [ɸu] also occurs |

| /si/ | /si/ | /hi/, [çi] also occurs |

| /su/ | /si/ | [ɕi]; formerly distinguished as [si] /hi/ [çi] also occurs |

| /tu/ | /t͡ɕi/ | [t͡ɕi]; formerly distinguished as [tsi] |

| /da/ | /ra/ | [d] and [ɾ] have merged |

| /de/ | /ri/ | |

| /do/ | /ru/ | |

| /ni/ | /ni/ | Moraic /ɴ/ also occurs |

| /nu/ | /nu/ | |

| /ha/ | /ɸa/ | /pa/ also occurs, but rarely |

| /hi/ | /pi/ ~ /hi/ | |

| /he/ | ||

| /mi/ | /mi/ | Moraic /ɴ/ also occurs |

| /mu/ | /mu/ | |

| /ri/ | /i/ | /iri/ unaffected |

| /wa/ | /wa/ | Tends to become /a/ medially |

Orthography

The Okinawan language was historically written using an admixture of kanji and hiragana. The hiragana syllabary is believed to have first been introduced from mainland Japan to the Ryukyu Kingdom some time during the reign of king Shunten in the early thirteenth century.[18][19] It is likely that Okinawans were already in contact with Chinese characters due to extensive trade between the Ryukyu Kingdom and China, Japan and Korea. However, hiragana gained more widespread acceptance throughout the Ryukyu Islands, and most documents and letters were uniquely transcribed using this script. The Omoro Saushi (おもろさうし), a sixteenth-century compilation of songs and poetry,[20] and a few preserved writs of appointments dating from the same century were written solely in Hiragana.[21] Kanji were gradually adopted due to the growing influence of mainland Japan and to the linguistic affinity between the Okinawan and Japanese languages.[22] However, it was mainly limited to affairs of high importance and to documents sent towards the mainland. The oldest inscription of Okinawan exemplifying its use along with Hiragana can be found on a stone stele at the Tamaudun mausoleum, dating back to 1501.[23][24]

After the invasion of Okinawa by the Satsuma clan in 1609, Okinawan ceased to be used in official affairs.[18] It was replaced by standard Japanese writing and a form of Classical Chinese writing known as kanbun.[18] Despite this change, Okinawan still continued to prosper in local literature up until the nineteenth century. Following the Meiji Restoration, the Japanese government abolished the domain system and formally annexed the Ryukyu Islands to Japan as the Okinawa Prefecture in 1879.[25] To promote national unity, the government then introduced standard education and opened Japanese-language schools based on the Tokyo dialect.[25] Students were discouraged and chastised for speaking or even writing in the local "dialect", notably through the use of "dialect cards" (方言札). As a result, Okinawan gradually ceased to be written entirely until the American takeover in 1945.

Since then, Japanese and American scholars have variously transcribed the regional language using a number of ad hoc romanization schemes or the katakana syllabary to demarcate its foreign nature with standard Japanese. Proponents of Okinawan tend to be more traditionalist and continue to write the language using hiragana with kanji. In any case, no standard or consensus concerning spelling issues has ever been formalized, so discrepancies between modern literary works are common.

Syllabary

(Technically, these are morae, not syllables.)

| イ | エ | ア | オ | ウ | ヤ | ヨ | ユ | ワ | ン | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ʔi | ʔe | ʔa | ʔo | ʔu | ʔja | ʔjo | ʔju | ʔwa | ʔɴ | |

| [ʔi] | [ʔe] | [ʔa] | [ʔo] | [ʔu] | [ʔja] | [ʔjo] | [ʔju] | [ʔɰa] | [ʔn] [ʔm] | |

| イ/ユィ | エ/イェ | ア | オ/ヲ | ウ/ヲゥ | ヤ | ヨ | ユ | ヱ | ワ | ン |

| i | e | a | o | u | ja | jo | ju | we | wa | ɴ |

| [i] [ji] | [e] [je] | [a] | [o] [wo] | [u] [wu] | [ja] | [jo] | [ju] | [ɰe] | [ɰa] | [n] [m] [ŋ] [ɴ] |

| ヒ | ヘ | ハ | ホ | フ | ヒャ | ヒョ | ヒュ | - | フヮ | |

| hi | he | ha | ho | hu | hja | hjo | hju | ― | hwa | |

| [çi] | [çe] | [ha] | [ho] | [ɸu] | [ça] | [ço] | [çu] | ― | [ɸa] | |

| ギ | ゲ | ガ | ゴ | グ | ギャ | - | - | グヱ | グヮ | |

| gi | ge | ga | go | gu | gja | ― | ― | gwe | gwa | |

| [ɡi] | [ɡe] | [ɡa] | [ɡo] | [ɡu] | [ɡja] | ― | ― | [ɡʷe] | [ɡʷa] | |

| キ | ケ | カ | コ | ク | キャ | - | - | クヱ | クヮ | |

| ki | ke | ka | ko | ku | kja | ― | ― | kwe | kwa | |

| [ki] | [ke] | [ka] | [ko] | [ku] | [kja] | ― | ― | [kʷe] | [kʷa] | |

| チ | チェ | チャ | チョ | チュ | - | - | - | - | - | |

| ci | ce | ca | co | cu | ― | ― | ― | ― | ― | |

| [ʨi] | [ʨe] | [ʨa] | [ʨo] | [ʨu] | ― | ― | ― | ― | ― | |

| ジ | ジェ | ジャ | ジョ | ジュ | - | - | - | - | - | |

| zi | ze | za | zo | zu | ― | ― | ― | ― | ― | |

| [ʥi] | [ʥe] | [ʥa] | [ʥo] | [ʥu] | ― | ― | ― | ― | ― | |

| シ | シェ | サ | ソ | ス | シャ | - | シュ | - | - | |

| si | se | sa | so | su | sja | ― | sju | ― | ― | |

| [ɕi] | [ɕe] | [sa] | [so] | [su] | [ɕa] | ― | [ɕu] | ― | ― | |

| ディ | デ | ダ | ド | ドゥ | ― | ― | ― | ― | ― | |

| di | de | da | do | du | ― | ― | ― | ― | ― | |

| [di] | [de] | [da] | [do] | [du] | ― | ― | ― | ― | ― | |

| リ | レ | ラ | ロ | ル | ― | ― | ― | ― | ― | |

| ri | re | ra | ro | ru | ― | ― | ― | ― | ― | |

| [ɾi] | [ɾe] | [ɾa] | [ɾo] | [ɾu] | ― | ― | ― | ― | ― | |

| ティ | テ | タ | ト | トゥ | - | - | - | - | - | |

| ti | te | ta | to | tu | ― | ― | ― | ― | ― | |

| [ti] | [te] | [ta] | [to] | [tu] | ― | ― | ― | ― | ― | |

| ミ | メ | マ | モ | ム | ミャ | ミョ | - | - | - | |

| mi | me | ma | mo | mu | mja | mjo | ― | ― | ― | |

| [mi] | [me] | [ma] | [mo] | [mu] | [mja] | [mjo] | ― | ― | ― | |

| ビ | ベ | バ | ボ | ブ | ビャ | ビョ | ビュ | - | - | |

| bi | be | ba | bo | bu | bja | bjo | bju | ― | ― | |

| [bi] | [be] | [ba] | [bo] | [bu] | [bja] | [bjo] | [bju] | ― | ― | |

| ピ | ペ | パ | ポ | プ | ピャ | - | ピュ | - | - | |

| pi | pe | pa | po | pu | pja | ― | pju | ― | ― | |

| [pi] | [pe] | [pa] | [po] | [pu] | [pja] | ― | [pju] | ― | ― | |

| ッ | ||||||||||

| q | ||||||||||

| [h] [j] [s] [t] [p] | ||||||||||

| ー | ||||||||||

| ᴇ | ||||||||||

| [ː] |

Grammar

Okinawan follows a subject>object>verb word order and makes large use of particles as in Japanese. Okinawan dialects retain a number of grammatical features of classical Japanese, such as a distinction between the terminal form (終止形) and the attributive form (連体形), the genitive function of が ga (lost in the Shuri dialect), the nominative function of ぬ nu (Japanese: の no), as well as honorific/plain distribution of ga and nu in nominative use.

| 書く kaku to write | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classical | Shuri | |||

| Irrealis | 未然形 | 書か | kaka- | kaka- |

| Continuative | 連用形 | 書き | kaki- | kachi- |

| Terminal | 終止形 | 書く | kaku | kachun |

| Attributive | 連体形 | 書く | kaku | kachuru |

| Realis | 已然形 | 書け | kake- | kaki- |

| Imperative | 命令形 | 書け | kake | kaki |

One etymology given for the -un and -uru endings is the continuative form suffixed with uri (Classical Japanese: 居り wori, to be; to exist): -un developed from the terminal form uri; -uru developed from the attributive form uru, i.e.:

- kachuru derives from kachi-uru;

- kachun derives from kachi-uri; and

- yumun (Japanese: 読む yomu, to read) derives from yumi + uri.

A similar etymology is given for the terminal -san and attributive -saru endings for adjectives: the stem suffixed with さ sa (nominalises adjectives, i.e. high → height, hot → heat), suffixed with ari (Classical Japanese: 有り ari, to exist; to have), i.e.:

- takasan (Japanese: 高い takai, high; tall) derives from taka-sa-ari;

- achisan (Japanese: 暑い atsui, hot; warm) derives from atsu-sa-ari; and

- yutasaru (good; pleasant) derives from yuta-sa-aru.

Particles

The Okinawan topic particle is ya (や), which corresponds with Japanese wa (は). However, apart from classical literature, ya assimilates into the preceding word in different ways; it remains separate only after long vowels. Likewise, the particle n (ん; "also", "even", "too"), corresponding to Japanese mo (も), will result in the addition of a vowel between it and a preceding moraic nasal n; if the word previously ended in a vowel in an earlier form of the language, it is likely to use that vowel.

The Okinawan subject particle distinguishes between ga (が) nu (ぬ, equivalent to Japanese の no), in honorific/plain distribution. This contrasts with Japanese, where the use of no as a subject particle is restricted to attributive clauses in the form "noun + の + attributive verb + noun".

Modern Okinawan does not use a direct-object marker, as in casual Japanese speech. However, classical literature uses the particle yu (ゆ, written as yo よ prior to the vowel shift), cognate to Japanese を wo, where appropriate.

- This list is incomplete; you can help by expanding it.

| Japanese | Okinawan | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| は (wa?) | や (ya?) | Topic particle for long vowels, proper nouns, or names. For other nouns, the particle fuses with short vowels. a → aa, i → ee, u → oo, e → ee, o → oo, n → noo.

|

| の (no?) | ぬ (nu?) | Possessive particle; acts like 's in English. |

| です (desu?) | やいびーん (yaibiin?) | "To be". Informal form yan. |

| を (o?) | Ø (Archaic: ゆ (yu?)

) |

Modern Okinawan does not use an object particle. "yu" exists mainly in old literary composition. |

| が (ga?) | ぬ (nu?) | Subject particle. Informal form ga. |

| も (mo?) | ん (n?) | "Also". |

| Preceding syntactic element | Example sentence | Translation |

|---|---|---|

| bikee/biken びけーん |

Translates as "only"; limit. For verbs "uppi" is used | |

| Nouns | rōmaji bikeen nu sumuchi ローマ字びけーんぬ書物。 | a rōmaji-only book |

| Verbs (volitional) | Ninjibusharu uppi nindin sumabiin. 寝んじ欲しゃるうっぴ寝んでぃん済まびいん。 | You can sleep as much as you want [to sleep]. |

| wuti/wutooti をぅてぃ・をぅとーてぃ |

Indicates the location where an action pertaining to an animate subject takes place. をぅとーてぃ wutooti is the progressive form of をぅてぃ wuti, and both derive from the participle form of the verb をぅん wun "to be, to exist". | |

| Nouns: location | Kuma wutooti yukwibusan. くまをぅとーてぃ憩ぃ欲さん。 | I want to rest here. |

| nkai んかい |

Translates as "to, in"; direction | |

| Nouns: direction | Uchinaa nkai mensooree! 沖縄んかいめんそーれー! | Welcome to Okinawa! |

| atai あたい |

Translates as "as much as", upper limit | |

| Nouns: For nouns yaka is used | Ari yaka yamatuguchi nu jooji ya aran. 彼やか大和口ぬ上手やあらん。 | My Japanese isn't as good as his |

| Verbs | Unu tatimunoo umuyuru atai takakooneeyabiran うぬ建物ー思ゆるあたい高こーねーやびらん。 | That building is not as tall as you imagine it to be |

| saani/saai/sshi/shee さーに・さーい・っし・しぇー |

Indicates the means by which something is achieved. | |

| Nouns | basusshi ichabira. バスっし行ちゃびら。 | Let's go by bus |

| Nouns: language | Uchinaaguchisaani tigami kachan. 沖縄口さーに手紙書ちゃん。 | I wrote the letter in Okinawan. |

| kuru/guru くる・ぐる (頃) |

Translates as "around, about, approximately" Kuru functions as an adverb and may be followed by nu. | |

| Nouns | San-ji guru nkai ichabira. 三時ぐるんかい行ち会びら。 | Let's meet around 3 o'clock. |

| kuree/guree くれー・ぐれー (位) |

Translates as "around, about, approximately" Kuree functions as an adverb and may be followed by ぬ. | |

| Nouns | Juppun kuree kakayun 十分くれーかかゆん。 | It takes about 10 minutes. |

| yatin やてぃん |

Translates as "even, or, but, however, also in" | |

| Nouns, particles: "even" | Uchuu kara yatin manri-nu-Choojoo nu miiyun. 宇宙からやてぃん万里ぬ長城ぬ見ーゆん。 | The Great Wall of China can be seen even from space. |

| Nouns: "also in" | Yamatu yatin inchirii-n guchi binchoosun 大和やてぃんいんちりーん口を勉強すん。 | In Japan also, we study English. |

| Beginning of phrase: "but, however, even so". In this case, "yashiga" is commonly used | yashiga, wannee an umuran やしが、我んねーあん思らん。 | But I don't think so. |

| madi までぃ (迄) |

Translates to: "up to, until, as far as" Indicates a time or place as a limit. | |

| Nouns (specifically places or times) | Kunu denshaa, Shui madi ichabiin. くぬ電車ー、首里までぃ行ちゃびーん。 | This train goes as far as Shuri. |

| Verbs | Keeru madi machooibiin. 帰るまでぃ待ちょーいびーん。 | I'll wait until you come home. |

Notes

- ↑ Okinawan at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015)

- ↑ Nordhoff, Sebastian; Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2013). "Central Okinawan". Glottolog. Leipzig: Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology.

- ↑ Mimizun.com 2005, Comment #658 – 45-CAC-ai comprises most of Central Okinawa, including Shuri (Naha), Ginowan and Nishihara; 45-CAC-aj comprises the southern tip of Okinawa Island, including Itoman, Mabuni and Takamine; 45-CAC-ak encompasses the region west of Okinawa Island, including the Kerama Islands, Kumejima and Aguni.

- ↑ Lewis 2009.

- ↑ Moseley 2010.

- ↑ Kerr 2000, p. xvii.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Brown & Ogilvie 2008, p. 908.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Kaplan 2008, p. 130.

- ↑ Noguchi 2001, p. 87.

- ↑ Noguchi 2001, p. 76.

- ↑ Hung, Eva and Judy Wakabayashi. Asian Translation Traditions. 2014. Routledge. Pg 18.

- ↑ http://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2012/05/19/national/okinawans-push-to-preserve-unique-language/#.VNrermK9KK0

- ↑ Noguchi & Fotos 2001, p. 81.

- ↑ Miyara 2009, p. 179.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Curry 2004, §2.2.2.1.9.

- ↑ Miyara 2009, p. 186.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 Noguchi 2001, p. 83.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 Kodansha 1983, p. 355.

- ↑ OPG 2003.

- ↑ Kerr 2000, p. 35.

- ↑ Takara 1994-1995, p. 2.

- ↑ WPL 1977, p. 30.

- ↑ Ishikawa 2002, p. 10.

- ↑ Okinawa Style 2005, p. 138.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Tanji 2006, p. 26.

References

- (Japanese) "民族、言語、人種、文化、区別スレ". Mimizun.com. 2005-08-31. Retrieved 2010-12-26.

- Moseley, Christopher (2010). "Atlas of the World’s Languages in Danger" (3rd ed.). UNESCO Publishing. Retrieved 2010-12-25.

- Kerr, George H. (2000). Okinawa, the history of an island people. Tuttle Publishing. ISBN 0-8048-2087-2.

- Brown, Keith; Ogilvie, Sarah (2008). Concise encyclopedia of languages of the world. Elsevier. ISBN 0-08-087774-5.

- Kaplan, Robert B. (2008). Language Planning and Policy in Asia: Japan, Nepal, Taiwan and Chinese characters. Multilingual Matters. ISBN 1-84769-095-5.

- Noguchi, Mary Goebel; Fotos, Sandra (2001). Proto-Japanese: issues and prospects. Multilingual Matters. ISBN 1-85359-490-3.

- Miyara, Shinsho (2009). "Two Types of Nasal in Okinawa" (PDF). 言語研究(Gengo Kenkyu) (University of the Ryukyus). Retrieved 2010-12-25.

- Curry, Stewart A. (2004). Small Linguistics: Phonological history and lexical loans in Nakijin dialect Okinawan. Ph.D. - East Asian Languages and Literatures (Japanese), University of Hawaii at Manoa.

- Takara, Kurayoshi (1994–1995). "King and Priestess: Spiritual and Political Power in Ancient Ryukyu" (PDF). The Ryukyuanist (Shinichi Kyan) (27). Retrieved 2011-01-23.

- Ishikawa, Takeo (April 2002). 新しいまちづくり豊見城市 (PDF). しまてぃ (in Japanese) (建設情報誌) (21). Retrieved 2011-03-14.

- (Japanese) "Worldwide Heritages in Okinawa: Tamaudun". 沖縄スタイル (枻出版社) (07). 2005-07-10. ISBN 4-7779-0333-8. Retrieved 2011-03-14.

- Kodansha – encyclopedia of Japan 6. Kodansha. 1983. ISBN 0-87011-626-6.

- Working papers in linguistics 9. Dept. of Linguistics, University of Hawaii. 1977.

- "King Shunten 1187-1237". Okinawa Prefectural Government. 2003. Retrieved 2011-03-14.

- Tanji, Miyume (2006). Myth, protest and struggle in Okinawa. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 0-415-36500-7.

- Noguchi, M.G. (2001). Studies in Japanese Bilungualism. Multilingual Matters Ltd. ISBN 978-1853594892.

- Davis, Christopher (2013). "The Role of Focus Particles in Wh-Interrogatives: Evidence from a Southern Ryukyuan Language" (PDF). University of the Ryukyus. Retrieved 2014-04-19.

External links

| Okinawan language test of Wikipedia at Wikimedia Incubator |

| Okinawan language repository of Wikisource, the free library |

- 首里・那覇方言概説(首里・那覇方言音声データベース)

- うちなあぐち by Kiyoshi Fiza, an Okinawan language writer.