Oirat language

| Oirat | |

|---|---|

|

ᡆᡕᡅᠷᠠᡑ ᡘᡄᠯᡄᠨ Oirad kelen ᠮᠣᠩᠭᠣᠯ ᠬᠡᠯᠡᠨ ᠦ ᠣᠶᠢᠷᠠᠳ ᠠᠶᠠᠯᠭᠤ Mongγol kelen-ü Oyirad ayalγu | |

| Native to | Mongolia, Russia, People's Republic of China, Kyrgyzstan[1] |

| Region | Khovd, Uvs, [2] Bayan-Ölgii,[3] Kalmykia, Xinjiang, Gansu, Qinghai |

| Ethnicity | Oirats |

Native speakers | 360,000 (2007–2010)[4] |

|

Mongolic

| |

Standard forms | |

| Clear script (China: unofficial), Cyrillic (Russia: official) | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-2 |

xal |

| ISO 639-3 |

Either: xal – Modern Oirat xwo – Written Oirat |

Linguist list |

xwo Written Oirat |

| Glottolog |

kalm1243[5] |

| Linguasphere |

part of 44-BAA-b |

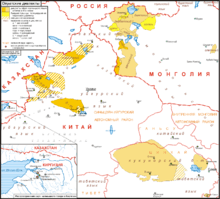

Oirat (Clear script: ᡆᡕᡅᠷᠠᡑ ᡘᡄᠯᡄᠨ Oirad kelen; Kalmyk: Өөрд, Khalkha-Mongolian: Ойрад) belongs to the group of Mongolic languages. Scholars differ as to whether they regard Oirat as a distinct language[7] or a major dialect of the Mongolian language.[8] Oirat speaking areas are scattered across the far west of the Mongolian state,[9] the northwest of People's Republic of China (mainly in Xinjiang, but even Deed Mongol in Qinghai and, with a tiny population, in Gansu),[9] and Russia's Caspian coast, where its major variety is Kalmyk.[10] In all three nations, Oirat has become variously endangered or even obsolescent as a direct result of government actions or as a consequence of social and economic policies. Its most widespread tribal dialect, which is spoken in all of these nations, is Torgut.[1][9] The term Oirat or, more precisely, Written Oirat is sometimes also used to refer to the language of historical documents written in the Clear script.[11]

In Mongolia, there are seven historical Oirat dialects, each corresponding to a different tribe:[12]

- Dörbet is spoken in half of the sums of Uvs Province and in Dörgön, Khovd Province

- Bayat in the sums of Malchin, Khyargas, Tes and Züüngovi, Uvs

- Torgut in Bulgan sum, Khovd

- Uriankhai in the sums of Duut and Mönkhkhairkhan, Khovd and in the sums of Altai, Buyant and Bulgan, Bayan-Ölgii Province

- Ööld in Erdenebüren, Khovd

- Zakhchin in the sums of Mankhan, Altai, Üyench, Zereg and Möst, Khovd

- Khoton (originally of Turkic origin) in Tarialan, Uvs. The Khoton were deported by the Zunghars from Central Asian cities to Western Mongolia, lost their original Turkic language and speak a Dörböd dialect of Oirat.[13][14]

There are some varieties that are difficult to classify. The Alasha dialect in Alxa League in Inner Mongolia originally belonged to Oirat[15] and has been classified as such by some because of its phonology.[1] But it has been classified by others as Mongolian proper because of its morphology.[16] The Darkhad dialect in Mongolia's Khövsgöl Province has variously been classified as Oirat, Mongolian proper, or (less often) Buryat.[17]

Oirat is endangered in all areas where it is spoken. In Russia, the killing of a large fraction of the Kalmyk population and the destruction of their society as consequences of the Kalmyk deportations of 1943, along with the subsequent imposition among them of Russian as the sole official language have rendered the language obsolescent: it is almost exclusively the elderly that have a fluent command of Kalmyk.[18] In China, while Oirat is still quite widely used in its traditional ranges and there are many monolingual speakers,[19] a combination of government policies and social realities has created an environment deleterious to the use of this language: the Chinese authorities' adoption of Southern Mongolian as the normative Mongolian language,[20] new educational policies which have led to the virtual elimination of Mongolian schools in Xinjiang (there were just two left as of 2009), policies aiming to curtail nomadism, and the limited occupational prospects in Chinese society for graduates of Mongolian schools.[21] As for Mongolia, the predominance of Khalkha Mongolian is bringing about the Khalkhaization of all other varieties of Mongolian.[22]

Script systems

Oirat has been written in two script systems: historically, the Clear script, which originated from the Mongolian script, was used. It uses modified letters shapes e.g. to differentiate between different rounded vowels, and it uses a small stroke on the right to indicate vowel length. It was retained longest in China where it can still be found in an occasional journal article. In Kalmykia, a Cyrillic-based script system has been implemented. It is strictly phonemic, not representing epenthetic vowels, and thus doesn’t show syllabification. In Mongolia, Central Mongolian minority varieties have no status, thus Oirats are supposed to use Mongolian Cyrillic which de facto only represents Khalkha Mongolian. In China, Buryat and Oirat are considered non-standard as compared to Southern Mongolian and are therefore supposed to use the Mongolian script and Southern Mongolian grammar (if not, as in current practice, rather Mandarin Chinese and Hanzi) for writing.

Bibliography

- Birtalan, Ágnes (2003): Oirat. In: Janhunen (ed.) 2003: 210-228.

- Bitkeeva, Aisa (2006): Kalmyckij yazyk v sovremennom mire. Moskva: NAUKA.

- Bitkeeva, Aisa (2007): Ethnic Language Identity and the Present Day Oirad-Kalmyks. Altai Hakpo, 17: 139-154.

- Bläsing, Uwe (2003): Kalmuck. In: Janhunen (ed.) 2003: 229-247.

- Chuluunbaatar, Otgonbayar (2008): Einführung in die mongolischen Schriften. Hamburg: Buske.

- Coloo, Ž. (1988): BNMAU dah’ mongol helnii nutgiin ajalguuny tol’ bichig: oird ayalguu. Ulaanbaatar: ŠUA.

- Indjieva, Elena (2009): Oirat Tobi: Intonational structure of the Oirat language. University of Hawaii. Dissertation.

- Janhunen, Juha (ed.) (2003): The Mongolic languages. London: Routledge.

- Katoh T., Mano S., Munkhbat B., Tounai K., Oyungerel G., Chae G. T., Han H., Jia G. J., Tokunaga K., Munkhtuvshin N., Tamiya G., Inoko H.: Genetic features of Khoton Mongolians revealed by SNP analysis of the X chromosome. Molecular Life Science, School of Medicine, Tokai University, Bohseidai, Isehara, Kanagawa, 259-1193, Japan. [Gene. 12 Sep. 2005].

- Sanžeev, G. D. (1953): Sravnitel’naja grammatika mongol’skih jazykov. Mosvka: Akademija nauk SSSR.

- Sečenbaγatur, Qasgerel, Tuyaγ-a, B. ǰirannige, U Ying ǰe (2005): Mongγul kelen-ü nutuγ-un ayalγun-u sinǰilel-ün uduridqal. Kökeqota: Öbür mongγul-un arad-un keblel-ün qoriy-a.

- Svantesson, Jan-Olof, Anna Tsendina, Anastasia Karlsson, Vivan Franzén (2005): The Phonology of Mongolian. New York: Oxford University Press.

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Svantesson et al. 2005: 148

- ↑ Svantesson et al. 2005: 141

- ↑ Coloo 1988: 1

- ↑ Modern Oirat at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015)

Written Oirat at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) - ↑ Nordhoff, Sebastian; Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2013). "Kalmyk". Glottolog. Leipzig: Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology.

- ↑ cp. the distribution given by Svantesson et al. 2005: 141

- ↑ Birtalan 2003. Note that she is not altogether clear about that matter as she writes: "For the present purpose, Spoken Oirat, from which Kalmuck is excluded, may therefore be treated as a more or less uniform language." (212). See also Sanžeev 1953

- ↑ Sečenbaγatur et al. 2005

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Sečenbaγatur et al. 2005: 396-398

- ↑ Sečenbaγatur et al. 2005, Bläsing 2003: 229

- ↑ Birtalan 2003: 210-211

- ↑ Coloo 1988: 1-6

- ↑ Library of Congress: Khoton (Mongolian people)

- ↑ Katoh et al. 2005

- ↑ Sečenbaγatur et al. 2005: 265-266

- ↑ Sečenbaγatur et al. 2005: 190-191

- ↑ See literature given in Sanžaa and Tujaa 2001: 33-34

- ↑ Bitkeeva 2007; for details see Bitkeeva 2006

- ↑ Bitkeeva 2007

- ↑ Sečenbaγatur et al. 2005: 179

- ↑ Indjieva 2009: 59-65

- ↑ Coloo 1988: III-IV

- ↑ Chuluunbaatar 2008: 41

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| Kalmyk edition of Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia |