Octoechos (liturgy)

The liturgical book called Octoechos (from the Greek: ἡ Ὀκτώηχος [okˈtoixos];[1] from ὀκτώ "eight" and ἦχος "sound, mode" called echos; Slavonic: Осмѡгласникъ, Osmoglasnik from о́смь "eight" and гласъ "voice, sound") contains a repertoire of hymns ordered in eight parts according to the eight echoi (tones or modes). Originally created as a hymn book with musical notation in the Stoudios monastery during the 9th century, it is used until nowadays in many rites of Eastern Christianity. The hymn book has something in common with the book tonary of the Western Church. Both contained the melodic models of the octoechos system, but the tonary served simply for a modal classification, while the book octoechos is as well organized as a certain temporal of several eight week periods and the word itself means the repertoire of hymns sung during the celebrations of the Sunday Office.

Performing an avtomelon over a kontakion by Romanos

Kathismata, odes or kontakia are set in a strict meter—a rhythm within a fixed number of verses as a strophe, a fixed number of syllables and accents as a verse. Despite the meter it is possible to arrange a complex poem like the prooimion of a Christmas kontakion composed by Romanos the Melodist which has its own history as a kontakion with its music and text,[2] according to the simple melodic model of a sticheron in echos tritos of the Octoechos. In the current tradition the kontakion exists as well as avtomelon—as a model to recite stichera prosomoia which was as well translated into Old Church Slavonic.

The arrangement of the syllables with their metric accentuation are composed as a well-known hymn tune or sticheron avtomelon within the melos of a certain echos. These melodic stichera are called automela, because they can easily adapted to other texts, even if the number of syllables of verse varies—the so-called "prosomoia."[note 1] The avtomelon which precedes the kontakion for Christmas, is recited today with a simple melody in a rather sophisticated troparic melos of echos tritos:[3]

Ἡ Παρθένος σήμερον τὸν ὑπερούσιον τίκτει

καὶ ἡ γῆ τὸ σπήλαιον τῷ ἀπροσίτῳ προσάγει,

Ἄγγελοι μετά ποιμένων δοξολογούσι,

Μάγοι δὲ μετά ἀστέρος ὁδοιπορούσιν,

δι’ ἡμάς γὰρ ἐγεννήθη παιδίον νέον,

ὁ πρὸ αἰώνων Θεός.[1]

- ^ Modern avtomelon over the Prooimion of the Christmas Kontakion by Romanos: Romanos the Melodist. "Avtomelon Ἡ Παρθένος σήμερον". Greek-Byzantine Choir. Slavonic Kondak sung in Valaamskiy Rozpev (Valaam Monastery): Romanos the Melodist. "Kondak Дева днесь". Valaam: Valaam Monastery Choir.

A hymn may more or less imitate an automelon melodically and metrically—depending, if the text has exactly the same number of syllables with the same accents as those of verses in the corresponding automelon. Such a hymn was called sticheron prosomoion, the echos and opening words of the sticheron avtomelon were usually indicated.[note 2] For example, the Octoechos' kontakion for Sunday Orthros in echos tritos has the indication, that it should be sung to the melody of the above Christmas kontakion.[note 3] Both kontakia have nearly the same number of syllables and accents within its verses, so the exact melody of the former is slightly adapted to the latter, its accents have to be sung with the given accentuation patterns.[note 4]

The printed book Octoechos with the Sunday cycles is often without any musical notation and the determination of a hymn's melody is indicated by the echos or glas according to the section within the book and its avtomelon, a melodic model defined by the melos of its mode. Since this book collects the repertoire of melodies sung every week, educated chanters knew all these melodies by heart, and they learnt how to adapt the accentuation patterns to the printed texts of the hymns while singing out of other text books like the menaion.

Greek octoechos and parakletike

Types of octoechos books

The Great Octoechos (ὅκτώηχος ἡ μεγάλη) or Parakletike contained as well the proper of office hymns for each weekday.[4][note 5] The hymns of the books octoechos and heirmologion had been collected earlier in a book called "troparologion" or "tropologion". It already existed during the 5th century in the Patriarchate of Antiochia, before it became a main genre of the centers of an octoechos hymn reform in the monasteries of Saint Catherine on Mount Sinai and Mar Saba in Palestine, where St. John Damascene (c. 676–749) and Cosmas of Maiuma created a cycle of stichera anastasima.[5] Probably for this reason John of Damascus is regarded as the creator the Hagiopolitan Octoechos and the treatise Hagiopolites itself claims his authorship right at the beginning. It has only survived completely in a 14th-century copy, but its origin dates probably back to the time between the council of Nicaea and the time Joseph the Hymnographer (~816-886), when the treatise could still have introduced the book tropologion. The earliest papyrus sources of the Tropologion can be dated to the 6th century:[6]

Choral singing saw its most brilliant development in the temple of Holy Wisdom in Constantinople during the reign of Emperor Justinian the Great. National Greek musical harmonies, or modes — the Dorian, Phrygian, Lydian, and Mixolydian modes — were adapted to the needs of Christian hymnography. Then John of Damascus started a new, third period in the history of Church singing. He introduced what is known as the osmoglasie — a system of singing in eight tones, or melodies —, and compiled a liturgical singing book bearing the title "Ochtoechos," which literally signifies "the book of the eight tones."[7]

The tropologion was expanded upon by St. Cosmas of Maiuma († 773), Theodore the Studite († 826) and his brother Joseph of Thessalonica († 832),[8] Theophanes the Branded (c. 775-845), the hegoumenai and hymnographers Kassia (810-865) and Theodosia, Thekla the Nun, Metrophanes of Smyrna († after 880),[9] Paul, Metropolit of Amorium, and by the emperors Leo VI and Constantine VII (10th c) as well as numerous anonymous authors. The earliest state of an octoechos collection of the Sunday canons is Ms. gr. 1593 of the Library at Saint Catherine's Monastery (about 800).[10] This reduced version was simply called Octoechos and it was often the last part of the sticherarion, the new notated chant book of the reformers.

Until the 14th century the book Octoechos was ordered according to hymn genre of the repertoire.[11] Later the thematic structure of the stichera anastasima which had to be sung during Hesperinos on Saturday and during Orthros on Sunday, were emphasised and ordered according to the eight echoi, each of the eight parts structured according to the order, as they had to be sung during the evening and morning service. They became a well structured book for the daily use of chanters like the later book Anastasimatarion or in Slavonic Voskresni).[12] Since the 17th century different collections of the Octoechos had been separated as own books about certain Hesperinos psalms like the Anoixantarion an octoechos collection for the psalm 103, the Kekragarion for psalm 140, and the Pasapnoarion for the psalm verse 150:6.[13]

Types of stichera

- Stichera anastasima. In the new book anastasimatarion (voskresnik) there are 24 stichera anastasima ("resurrection ideomela") which are usually ascribed to John of Damascus, three of them in each echos. Most of them do not appear within the book Octoechos before the 15th century.

- Stichera anatolika. Composed about the longest stichoi concerning the resurrection motive. The name probably derived from a certain composer or from their local origin.

- Stichera alphabetika. 24 stichera composed in a style similar to the anatolika. They are usually ordered according to the alphabet concerning their incipit.

- Anavathmoi. The antiphons of the anavathmoi are structured as eight parts according to the octoechos, each one consisting of three troparia. The kyrioi echoi (authentic modes) are composed about verses of the "Gradual psalms," the plagioi echoi (plagal modes) usually begin with psalm 119. The last sticheron of each antiphon usually begins with ἁγιῷ πνεύματι. The anavathmoi were often a separated collection within the book Octoechos, which was no longer included in later books.

- Heothina anastasima. The eleven stichera of the heothina are ascribed to the Emperor Leo VI and are sung in connection with the Matins Gospel during Orthros. The first eight follow the the octoechos order, with the plagios tetartos in the enharmonic phthora nana. The ninth sticheron was composed in echos plagios protos, the tenth in the phthora nenano (plagios devteros), and the eleventh in the diatonic plagios tetartos.[14]

- Exaposteilaria anastasima. The eleven exaposteilaria anastasima are ascribed to Emperor Constantine VII. Created during the Macedonian renaissance, they are a later part of the repertoire which cannot be found in manuscripts before the 11th century. The cycle was sung since the Sunday following Pentecost, followed by a theotokion and a heothinon.

- Stichera dogmatika. These stichera are dedicated to the Mother of God (Theotokos) and they are called "dogmatika," because the hymns are about the dogmas concerned with the virgin Mary. The section of dogmatika, 24 with three for each echos, was usually completed with other Marianic hymns called "theotokia."

- Stichera staurosima and staurotheotokia. (devoted to the Holy Cross and to the Mother of God), sung on Wednesdays and Fridays.

The Octoechos also included other stichera dedicated to particular saints according to the provenance of a certain monastery, which also allows conclusions concerning place, where the chant book was used.

The temporal cycles and the prosomoia

The Sticherarion did not only include the book Octoechos, but also the books Menaion, Triodion and Pentecostarion. Nevertheless, certain stichera of the other books, stichera prosomoia which rather belonged to an oral tradition, becaused they were later composed by using the avtomela, were written in the book Octoechos, and usually outside the eight parts, if it was composed according to the octoechos order.[15] They were regarded as part of the book Octoechos, although they belonged rather to the temporal cycles.[16]

Nevertheless, a temporal eight-week-order was always the essential part of the Octoechos, at least as a liturgical concept. The temporal organisation of the mobile feast cycle and its lessons was result of the Studites reform since Theodore the Studites, their books were already translated by Slavic monks during the 9th century.[17] The eight tones can be found as the Paschal cycle (moveable cycle) of the church year, the so-called pentecostarion starting with the second Sunday of (the eighth day of) Easter, that week using the first tone, the next week using the second tone, and so, through all eight tones. The same cycle started in the triodion with the Lenten period until Easter,[note 6] with the Lenten Friday preceding the subsequent Palm Sunday.[note 7] Each day of the week has a distinct theme for which hymns in each tone are found in the texts of the Octoechos. During this period, the Octoechos is not sung on weekdays and it is furthermore not sung on Sundays from Palm Sunday through the Sunday of All Saints.[note 8]

After Pentecost, the singing of the Great Octoechos on weekdays continued until Saturday of Meatfare Week, on Sundays there was another cycle organised by the eleven heothina with their exaposteilaria and their theotokia.

In the daily practice the prosomeia of the Octoechos are combined with ideomela from the other books: On the fixed cycle, i.e., dates of the calendar year, the Menaion and on the movable cycle, according to season, the Lenten Triodion (in combination from the previous year's Paschal cycle). The texts from these volumes displace some of those from the Octoechos. The less hymns are sung from the Octoechos the more have to be sung from the other books. On major feast days, hymns from the Menaion entirely displace those from the Octoechos except on Sundays, when only a few Great Feasts of the Lord eclipse the Octoechos.

Note that the Octoechos contains sufficient texts, so that none of these other books needs to be used—a holdover from before the invention of printing and the completion and wide distribution of the rather large 12-volume Menaion—, but portions of the Octoechos (e.g., the last three stichera following "Lord, I have cried," the Hesperinos psalm 140) are seldom used nowadays and they are often completely omitted in the currently printed volumes.

The Old Church Slavonic reception of the Greek octoechos

Even before a direct exchange between Slavic monks and monks of the Stoudios Monastery, papyrus fragments offer evidence of earlier translations of Greek hymns. The early fragments show that hymns and their melodies developed independently in an early phase until the 9th century. Cyrill and Methodius and their followers within the Ohrid-School were famous for the translation of Greek hymnody between 863 and 893, but it is also a period of a reformative synthesis of liturgical forms, the creation of new hymnographical genres and their organisation in annual cycles.[18]

Slavic oktoich or osmoglasnik

Though the name of the book "Oktoich" derived from the Greek name Octoechos (Old Slavonic "Osmoglasnik," because "glas" is the Slavonic term for echos), the Slavic book did rather correspond to the unnotated Tropologion, and often it included the hymns of the Irmolog as well. The Slavic reception, although it can be regarded as faithful translation of the Byzantine books, is mainly based on early Theta notation, which was used by Slavic reformers in order to develop own forms of notation in Moscow and Novgorod (znamenny chant).[19] The translation activities between 1062 and 1074 at the Kievan Pechersky monastery had been realised without the help of South Slavic translators.[20] The earliest known Slavonic manuscripts with neumes date from the late 11th or 12th century (mainly Stichirar, Kondakar and Irmolog).

Glas ("voice") 1–4 are the authentic modes or kyrioi echoi, and the remaining 5–8 are the plagal modes or plagioi echoi, the latter term coming from the Medieval Greek plagios, "oblique" (from plagos, "side").[21] Unlike the Western octoechos, glas 5–8 (the plagioi echoi) used the same octave species like glas 1–4, but their final notes were a fifth lower on the bottom of the pentachord with respect to the finales of the kyrioi on the top of each pentachord, the melodic range composed in the plagioi was usually smaller. There are further subtle differences like microtonal shifts (melodic attraction) and accentuation patterns for those syllables which have a metric accent.

Today heirmological melodies have their own octoechos and their tempo, which employ a slightly modified scale for each tone are used primarily for canons;[22] in canons, each troparion in an ode uses the meter and melody of the ode's irmos (analogous to prosomoia for sticheraric modes of a tone) and, therefore, even when a canon's irmos is never sung, its irmos is nonetheless specified so as to indicate the melody.[23] A volume called an "Irmolog" contains the irmosi of all the canons of all eight tones as well as a few sundry other pieces of music.[24] Abridged versions of the Octoechos printed with musical notation were frequently published. As simple Octoechos they provided the hymns for the evening (večernaja molitva) and morning service (utrenna) between Saturday and Sunday.

Print editions with musical notation

In Russia the Oktoich was the very first book printed (incunabulum) in Cyrillic typeface, which was published in Poland (Kraków) in 149—by Schweipolt Fiol, a German native of Franconia. Only seven copies of this first publication are known to remain and the only complete one is in the collection of the Russian National Library.[25]

In 1905 the Zograf Monastery published a set of Slavonic chant books whose first volume is the Voskresnik with the repertoire of the simple Osmoglasnik.[26] Within the Russian Orthodox church a chant book Octoechos with notated with kryuki developed during the late fifteenth century. The first print edition Oktoikh notnago peniya, sirech' Osmoglasnik was published with Kievan staff notation in 1772. It included hymns in Znamenny Chant as well as the melodic models (avtomela) for different types of hymns for each Glas.[27]

Caveat

Northern Slavs in modern times often do not use the eight-tone music system—although they always do use the book Octoechos—rather singing all hymns in the same scale but with different melodies for each tone for each of several types of classifications of hymns.

Oriental hymnals

.jpg)

Since the earliest complete Tropologion is a Georgian Iadgari,[28] other hymn books have derived from the Hagiopolitan hymn reform which contain stichera and canons without being necessarily dependent on the Byzantine chant book Octoechos as it was created at the Stoudios Monastery.[29] The reason of the this independence is, that the church history of Armenia and Georgia preceded the Byzantine imperial age about 50 years. This section describes Oriental and Caucasian hymnals as they have been used by Armenians until the genocide by the end of the Ottoman Empire, and as they are still used among Orthodox Christians in Syria, Persia, Armenia and Georgia.

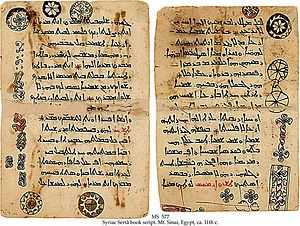

Syriac "Treasury of Chants"

The Syriac Orthodox Church also makes use of a system of eight modes (makams). Each hymn (Syriac: qolo, plural: qole) is composed in one of these eight modes. Some modes have variants (shuhlophe) similar to the "special melodies" mentioned above. Only skilled chanters can master these variants.

The modal cycle consists of eight weeks. Each Sunday or Feast day is assigned one of the eight modes. During the weekday offices, known in Syriac by the name Shhimo, the 1st and 5th modes are paired together, so are the 2nd and 6th, the 3rd and 7th, and the 4th and 8th. If a particular Sunday makes use of the 1st mode, the following Monday is sung with the 5th mode, Tuesday with the 1st mode, etc., with the pair alternating every day of the week (see the table provided in Guide to the Eight Modes in the External Links below).

The ecclesiastical year starts with Qudosh `Idto (The Consecration of the Church), a feast observed on the eighth Sunday before Christmas (Yaldo). The 1st mode is sung on this day. The following Sunday makes use of the 2nd mode, and so on, repeating the cycle until it starts again the next year. The cycle is interrupted only by feasts which have their own tones assigned to them. Similar to the Byzantine usage, each day of Easter Week has its own mode, except the Syriacs do not skip the 7th mode. Thus, the Sunday after Easter, called New Sunday (Hadto) is in the 8th mode rather than the 1st.

In one type of hymn used by the Syriac Church, the Qole Shahroye (Vigils), each of the modes is dedicated to a theme: The 1st and 2nd modes are dedicated to the Virgin Mary, the 3rd and 4th to the saints, the 5th and 6th to penitence, and the 7th and 8th to the departed.

The primary collection of hymns in the eight modes is the Beth Gazo d-ne`motho, or "Treasury of Chants."

Armenian Šaraknoc'

_Wellcome_L0031103.jpg)

In the Armenian Apostolic Church, the system of eight modes is referred to as oot tzayn (eight voices). Although there is no structural relation between the Greek and Armenian modes, the division into "Authentic" and "Plagal" modes is parallel. In Armenian terminology, the "Authentic" modes are referred to as "Voice" (Tzayn) and the "Plagal" modes are called "Side" (Koghm), and are utilized in the following order:

| Greek | Armenian |

|---|---|

| First (ἦχος πρῶτος) | First Voice (aradjin tzayn) |

| Plagal of the First (ἦχος πλάγιος τοῦ πρώτου) | First Side (aradjin koghm) |

| Second (ἦχος δεύτερος) | Second Voice (yerkrord tzayn) |

| Plagal of the Second (ἦχος πλάγιος τοῦ δευτέρου) | Second, Principal Side (yerkrord, awag koghm) |

| Third (ἦχος τρίτος) | Third Voice (yerrord tzayn) |

| Grave (ἦχος βαρύς) | Third Side, low voice (yerrord koghm, vaṙ tzayn) |

| Fourth (ἦχος τέταρτος) | Fourth Voice (tchorrord tzayn) |

| Plagal of the Fourth (ἦχος πλάγιος τοῦ τετάρτου) | Fourth Side, Last Voice (tchorrord koghm, verdj tzayn) |

This order is important, because it is the order in which the modes are used liturgically and different from the order of the Greek traditions. Instead of using one tone per week, the Armenians use one tone per day. Easter Sunday is always the First Voice, the next day is First Side, and so on throughout the year. However, the cycle does not actually begin on Easter day, but counts backwards from Easter Sunday to the First Sunday in Lent, which is always Forth Side, regardless of what mode the previous day was. Each mode of the oot tzayn has one or more tartzwadzk‘ (auxiliary) modes.

The Šaraknoc' is the book which contains the Šarakan, or Šaragan (Canons),[30] hymns which constitute the substance of the musical system of Armenian liturgical chant in the eight modes.[31] Originally, these were Psalms and Biblical Canticles that were chanted during the services. A Sharagan was composed of verses which were interspersed between the scriptural verses. Eventually, the Šarakan replaced the biblical text entirely. In addition, the eight modes are applied to the psalms of the Night office, called Kanonaklookh (Canon head). the Armenian Church also makes use of other modes outside of the oot tzayn.

Notes

- ↑ The Three Classes of Melodic Forms for Stichera, II. Automela (Samopodobny, Model Melodies)

- ↑ The Three Classes of Melodic Forms for Stichera, III. Prosomoia (Podobny, Special Melodies)

- ↑ See the article about the three melody types of stichera, where the texts of the two kontakia are compared as an illustration (idiomelon, avtomelon, prosomoion).

- ↑ The Three Classes of Melodic Forms for Stichera, I. Idiomela (Samoglasny, Independent Melodies).

- ↑ Octoechos is often used to describe a smaller volume that contains only the hymns for the Sunday services. In order to distinguish the longer version from the short one, the term Paraklētikē (Greek: Παρακλητική) can be used as well for the Great Octoechos. The word Paraklētikē comes from the Greek parakalein (παρακαλεῖν), meaning, "to supplicate" (the more penitential texts are found on weekdays).

- ↑ All of Great Lent, the periods of Cheesefare Week and Holy Week which are joined, respectively, to the beginning and end of Great Lent

- ↑ Each day of Bright Week (Easter Week) uses propers in a different tone, Sunday: Tone One, Monday: Tone Two, skipping the least festive of the tones, the grave (heavy) tone.

- ↑ Although many of the Sunday resurrection hymns are replicated in the Pentecostarion

See also

- Syriac sacral music

- Armenian chant

- Sticherarion

References

- ↑ The female form ἡ Ὀκτώηχος means the book (ἡ βίβλος) "octoechos" or "octaechos".

- ↑ Concerning the history of its translation in Old Church Slavonic Kondakars, see Roman Krivko (2011, 726).

- ↑ The Greek way definitely represents a monodic tradition of automelon as it had developed since the 7th century, while the polyphonic Russian way to perform the kontakion uses simpler forms of "echos-melodies" (the expression "na glas" is still used among Old Believers) (Shkolnik 1995).

- ↑ A Parakletike written during the 14th century can be studied online (D-Mbs Ms. cgm 205).

- ↑ From this early period there were only few Greek sources, but a recent study (Nikiforova 2013) of a tropologion at the St Catherine at Sinai could reconstruct the earlier form of the tropologion which preceded the book Octoechos.

- ↑ See the Georgian and Greek papyrus studies by Stig Frøyshov (2012) and Christian Troelsgård (2009).

- ↑ See Liturgics by Archbishop Averky.

- ↑ Theodore created the Triodion, the Pentecostarion, and the three antiphons of the anavathmoi of the Octoechos (Wolfram 2003).

- ↑ Theophanes created the Trinity Canon for the Sunday night service (mesonyktikon).

- ↑ Natalia Smelova (2011, 119 & 123) also mentions two contemporary compilations which were later translated into Syriac language: ET-MSsc Ms. gr. 776, GB-Lbl Ms. Add. 26113. Syro-Melkite translation activity reached its climax not earlier than during the 13th century like Sinait. gr. 261, a few manuscripts were also copied directly at Sinai.

- ↑ See for instance the octoechos part of the sticherarion of Copenhagen: stichera anastasima (f. 254r), alphabetika (f. 254v), anavathmoi and stichera anatolika (f. 255v), stichera heothina (f. 277v), dogmatika (f. 281v) and staurotheotikia (f. 289r).

- ↑ See the various printed editions in current use in Greece (Ephesios 1820, Phokaeos 1832), Bulgaria (Triandafilov 1847, Todorov 1914), Romania (Suceanu 1823, Stefanescu 1897), and Macedonia (Zografski 2005, Bojadziev 2011).

- ↑ The separation of this books can usually be found in anthologies ascribed to Panagiotes the New Chrysaphes (GB-Lbl Harley 1613, Harley 5544), but there is also a manuscript with composition of Petros Peloponnesios and his student Petros Byzantios organised as an Anastasimatarion and Doxastarion which preceded the printed editions (GB-Lbl Add. 17718).

- ↑ See the old sticherarion (DK-Kk NkS 4960, ff. 277v-281v).

- ↑ Irina Shkolnik (1998, 523) observed, that mainly automela were not written, because they were part of an oral tradition, while most of the prosomoia can only be found in later manuscripts since the 13th century.

- ↑ The early Prosomoia composed by Theodore the Studites for the evening service during Lenten period which belong to the book Triodion (Husmann 1972, 216-231). These prosomoia are not composed over stichera avtomela, but over stichera ideomela, especially compositions dedicated to martyres.

- ↑ Svetlana Poliakova (2009).

- ↑ Svetlana Poliakova (2009, 5;80-127) observed that most of Slavonic Triods have the prosomoia collection of Theodore the Studite, less the one composed by "Joseph" which were created by Theodore's brother, but more often by the later Sicilian composer Joseph the Hymnographer.

- ↑ Svetlana Poliakova (2009) studied mainly the Triod and the Pentekostarion Voskresensky (RUS-Mim Synodal Collection, Synod. slav. 319, Synod. slav. 27), while Dagmar Christian's (2001) forthcoming edition of the stichera avtomela and irmosi of the menaion is based on Synod. slav. 162.

- ↑ The evidence is given by the many differences between Russian and South-Slavic translations of typika and liturgical manuscripts and their different interpretations in the rubrics.

- ↑ See for example the very voluminous Parakletike written by Daniel Etropolski during the 17th century which also includes the canons, but only for Glas 5-8 (Sofia, Ms. НБКМ 187).

- ↑ For the current tradition see the print editions in use nowadays. The troparic meloi used in the Anastasimataria is usually close to the meloi used in the Heirmologion (see Chourmouzios' transcription of Petros Peloponnesios' Katavasies and Petros Byzantios' Heirmologion syntomon printed together in 1825). Mainly these two books composed in the last quarter of the 18th and transcribed in the early 19th century, are adapted to the Old Slavonic and the Romanian translation of the heirmologion.

- ↑ In medieval manuscripts it was enough to write the incipit of the text which identified the heirmos. As a melodic model it was known by heart. Often the Slavic book Oktoich is confused with the Irmolog (Sofia, Ms. НБКМ 989), but in fact the border between both was rather fluent within Slavic traditions.

- ↑ Archbishop Averky: "Liturgics — The Irmologion."

- ↑ See Treasures of the National Library of Russia, Petersburg.

- ↑ See also the recent edition by Kalistrat Zografski (2005).

- ↑ A later edition called the "Sputnik Psalomshcika" ("The Chanter's Companion") was republished in 1959 by Holy Trinity Monastery in Jordanville, NY, USA. "The Church Obihod of Notational Singing" contains, among other hymns, the repertoire of the Octoechos. Archbishop Averky: "Liturgics — On Music Books."

- ↑ Stig Frøyshov (2012).

- ↑ A Sticherarion with Byzantine notation written over Syriac hymns at Sinai proves that different branches of Orthodoxy existed (Mount Sinai, Saint Catherine's Monastery, Ms. syr. 261), but not all forms relied on Constantinopolitan reforms. See Heinrich Husmann (1975).

- ↑ See the illuminated manuscripts at The Walters Art Museum (W.547, W.545) and the printed edition (Constantinople 1790).

- ↑ It corresponds the Georgian Iadgari which is one of the earliest testimonies of the tropologion (Renoux 1993, Frøyshov 2012).

Sources

Tropologia (6th-12th century)

- "Vienna, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Papyrus Vindobonensis G 19.934" (PDF). Fragment of a 6th-century tropologion. Retrieved 4 October 2013.

Palaeo-Byzantine notation (10th–13th century)

- "Mount Sinai, St. Catherine's Monastery, Ms. syr. 261". Syriac Sticherarion written in Coislin Notation from Saint Catherine's Monastery (13th century). Retrieved 15 August 2012.

Middle Byzantine notation (13th–19th century)

- "Copenhagen, Det kongelige Bibliotek, Ms. NkS 4960, 4°, fol. 254r-294v". Oktoechos as part of a complete sticherarion (menaion, triodion, and pentekostarion) 14th century. Retrieved 31 October 2012.

- "Bucarest, Bibliotheca Academiei Române, Ms. gr. 953, ff. 336r-348v". Oktoechos in a complete Sticherarion with Menaion, Triodion and Pentekostarion (ca. 1400).

- Panagiotes the New Chrysaphes. "London, British Library, Harley Ms. 1613". Anthologia with Byzantine composers (Kekragarion, Ainoi, Pasapnoarion, Prokeimena, Sticherarion and Leitourgika) (17th century). British Library. Retrieved 3 May 2012.

- Panagiotes the New Chrysaphes. "London, British Library, Harley Ms. 5544". Papadike and the Kekragarion of Chrysaphes the New, and an uncomplete Anthology for the Divine Liturgies (17th century). British Library. Retrieved 3 May 2012.

- "Sofia, St. Cyril and St. Methodius National Library, Ms. НБКМ Гр. 62-61". Two Kekragaria with Papadike and stichera heothina (18th c.).

- Petros Peloponnesios; Petros Byzantios. "London, British Library, Ms. Add. 17718". Anastasimatarion and Doxastarion (about 1800). British Library. Retrieved 3 May 2012.

Oktoechoi, Parakletikai and Šaraknoc' without musical notation (11th-19th century)

- "Sofia, St. Cyril and St. Methodius National Library, Ms. НБКМ 989". Serbian Irmolog with troparia sorted according the Osmoglasnik (13th c.).

- "Munich, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Ms. cgm 205". Parakletike or Great Oktoechos composed in eight parts without musical notation (Greek monastery near Venice). 1355–1365.

- "Sofia, St. Cyril and St. Methodius National Library, Ms. НБКМ 187". Slavonic Oktoich with canons for Glas 5-8 (plagioi echoi) written by Hieromonachos Daniel Etropolski (17th c.).

- "Baltimore, The Walters Art Museum, Ms. W.547". Šaraknoc' (Շարակնոց) written by the priest Yakob Pēligratc‘i (commissioned by Člav, son of Nawasard, as a dedication to his sons) at Constantinople (1678).

- "Baltimore, The Walters Art Museum, Ms. W.545". Šaraknoc' (Շարակնոց) written by Awēt, probably at the Monastery of Surb Amenap'rkič in New Julfa, Isfahan, Iran (about 1700).

- "Šaraknoc' eražštakan ergec'mownk' hogeworakank' A[stowa]caynoc' ew erǰankac' s[r]b[o]c' vard[a]petac' hayoc' t'argmanč'ac". Constantinople: Universitäts- und Landesbibliothek Bonn. 1790.

Anastasimataria and Voskresnik with Chrysanthine notation (since 1814)

- Petros Peloponnesios (c. 1818). Gregorios the Protopsaltes (transcription), ed. "Αναστασιματάριον σύντομον κατά το ύφος της μεγάλης εκκλησίας μελοποιηθέν παρά κυρ Πέτρου Λαμπαδαρίου του Πελοποννησίου· εξηγηθέν κατά τον νέον της μουσικής τρόπον παρά Γρηγορίου Πρωτοψάλτου". Naoussa, Pontian's National Library of Argyroupolis 'Kyriakides', Ms. Sigalas 52. Naoussa: Aristotle University of Thessaloniki. Retrieved 9 August 2012.

- Ephesios, Petros Manuel, ed. (1820). Νέον Αναστασιματάριον μεταφρασθέν κατά την καινοφανή μέθοδον της μουσικής υπό των εν Κωνσταντινουπόλει μουσικολογιωτάτων Διδασκάλων και εφευρετών του νέου μουσικού συστήματος (PDF). Bucharest.

- Petros Peloponnesios the Lampadarios; Chourmouzios Chartophylakos (1832). Theodoros Phokaeos, ed. Αναστασιματάριον νέον μεταφρασθέντα εις το νέον της μουσικής σύστημα παρά του διδασκάλου Χουρμουζίου Χαρτοφύλακος, και του κυρίου Θεοδώρου Φωκέως. Περιέχον τα Αναστάσιμα του Εσπερινού, Όρθρου, και Λειτουργίας, μετά των αναστασίμων Κανόνων, Μαρτυρικών, και Νεκρωσίμων της Μεγάλης Τεσσαρακοστής, των τε Εωθινών, και των συντόνων Τιμιωτέρων. Τα πάντα καθώς την σήμερον ψάλλονται εις το Πατριαρχείον μεταφρασθέντα εις το νέον της μουσικής σύστημα παρά του διδασκάλου Χουρμουζίου Χαρτοφύλακος, και του κυρίου Θεοδώρου Φωκέως. Istanbul: Isaac De Castro.

- Triandafilov, Nikolaj, ed. (1847). Воскресникъ новъ – Който содержава воскресныте вечерны, ѹтренни, и ѹтренните стїхиры. Bucarest: Iosif Kopainig.

- Stefanescu, Lazar (1897). Teoria principiilor elementare de muzica bisericeasca şi Anastasimatarul teoretic şi foarte practic (PDF). Bucarest: Cărților Bisericescĭ.

- Todorov, Manasij Pop, ed. (1914). Воскресникъ сирѣчъ Оцмогласенъ Учебникъ съдържашъ воскресната служба и всизкитѣ подобин на осъмтѣхъ гласа. Sofia: Carska Pridvorna Pečatnica.

- Coman, Cornel; Duca, Gabriel, eds. (2002). Anastasimatarul cuviodului Macarie Ieromonahul su Adăuciri din cel Paharnicului Dimitrie Suceanu (PDF) (Vienna 1823, transliterated ed.). Bucarest: Editura Bizantina & Stavropoleos.

- Zografski, Kalistrat, ed. (2005). Источно Црковно Пѣнiе – Литургия и Воскресникъ. Skopje: Centar za vizantološki studii.

- Bojadziev, Vasil Ivanov, ed. (2011). Опсирен Псалтикиски Воскресник. Skopje: Centar za vizantološki studii.

Editions

- Christians, Dagmar, ed. (2001). Die Notation von Stichera und Kanones im Gottesdienstmenäum für den Monat Dezember nach der Hs. GIM Sin. 162: Verzeichnis der Musterstrophen und ihrer Neumenstruktur. Patristica Slavica 9. Wiesbaden: Westdt. Verl. ISBN 3-531-05129-6.

- Tillyard, H.J.W., ed. (1940–1949). The Hymns of the Octoechus. MMB Transcripta. 3 & 5. Copenhagen.

- Тvпико́нъ сiесть уста́въ (Title here transliterated into Russian; actually in Church Slavonic) (The Typicon which is the Order), Москва (Moscow, Russian Empire): Сvнодальная тvпографiя (The Synodal Printing House), 1907

Studies

- Archbishop Averky († 1976); Archbishop Laurus (2000). "Liturgics". Holy Trinity Orthodox School, Russian Orthodox Church Abroad, 466 Foothill Blvd, Box 397, La Canada, California 91011, USA. Retrieved 15 January 2012.

- Frøyshov, Stig Simeon R. (2012). "The Georgian Witness to the Jerusalem Liturgy: New Sources and Studies". In Bert Groen, Stefanos Alexopoulos, Steven Hawkes-Teeples (eds.). Inquiries into Eastern Christian Worship: Selected Papers of the Second International Congressof the Society of Oriental Liturgy (Rome, 17–21 September 2008). Eastern Christian Studies 12. Leuven, Paris, Walpole: Peeters. pp. 227–267.

- Husmann, Heinrich (1972). "Strophenbau und Kontrafakturtechnik der Stichera und die Entwicklung des byzantinischen Oktoechos". Archiv für Musikwissenschaft 34: 151–161; 213–234. doi:10.2307/930421.

- Husmann, Heinrich (1975). "Ein syrisches Sticherarion mit paläobyzantinischer Notation (Sinai syr. 261)". Hamburger Jahrbuch für Musikwissenschaft 1: 9–57.

- Jeffery, Peter (2001). "The Earliest Oktōēchoi: The Role of Jerusalem and Palestine in the Beginnings of Modal Ordering". The Study of Medieval Chant: Paths and Bridges, East and West; In Honor of Kenneth Levy. Woodbridge, Suffolk: Boydell Press. pp. 147–209. ISBN 0-85115-800-5.

- Krivko, Roman Nikolaevič (2011). "Перевод, парафраз и метр в древних славянских кондаках, II : Критика, история и реконструкция текстов [Translation, Paraphrase and Metrics in Old Church Slavonic Kontakia, II: Textual Critisism and Reconstruction]". Revue des études slaves 82 (4): 715–743. doi:10.3406/slave.2011.8134.

- Nikiforova, Alexandra (2013). "Tropologion Sinait. Gr. ΝΕ/ΜΓ 56–5 (9th c.): A new source for Byzantine Hymnography". Scripta & e-Scripta. International Journal for Interdisciplinary Studies 12: 157–185.

- Poliakova, Svetlana (June 2009). "Sin 319 and Voskr 27 and the Triodion Cycle in the Liturgical Praxis in Russia during the Studite Period" (PDF). Lissabon: Universidade Nova de Lisboa. Retrieved 19 April 2012.

- Renoux, Charles (1993). "Le Iadgari géorgien et le Šaraknoc' arménien". Revue des Études Arméniennes 24: 89–112. doi:10.2143/REA.24.0.2017113. ISSN 0080-2549.

- Shkolnik, Irina (1995). "To the Problem of the Evolution of the Byzantine Stichera in the Second Half of the V-VIIth Centuries, From the "Echos-Melodies" to the Idiomela" (PDF). In Dobszay, László. Cantus planus: Papers read at the 6th meeting, Eger, Hungary, 1993. Budapest: Hungarian Academy of Sciences. pp. 409–425. ISBN 9637074546.

- Shkolnik, Irina (1998). "Byzantine prosomoion singing, a general survey of the repertoire of the notated stichera models (automela)" (PDF). In Dobszay, László. Cantus Planus: Papers read at the 7th Meeting, Sopron, Hungary 1995. Budapest: Hungarian Academy of Sciences. pp. 521–537. ISBN 9637074678.

- Simmons, Nikita. "The Three Classes of Melodic Forms for Stichera". HYMNOGRAPHY. PSALOM – Traditional Eastern Orthodox Chant Documentation Project. Retrieved 16 January 2012.

- Smelova, Natalia (2011). "Melkite Syriac Hymns to the Mother of God (9th to 11th centuries): Manuscripts, Language and Imagery". In Leslie Brubaker, Mary B. Cunningham (eds.). The Cult of the Mother of God in Byzantium: Texts and Images. Aldershot: Ashgate. pp. 117–131. ISBN 9780754662662.

- Troelsgård, Christian (2009). "A New Source for the Early Octoechos? Papyrus Vindobonensis G 19.934 and its musical implications" (PDF). Proceedings of the 1st International Conference of the ASBMH. 1st International Conference of the ASBMH, 2007: Byzantine Musical Culture. Pittsburgh. pp. 668–679.

- Wolfram, Gerda (2003). "Der Beitrag des Theodoros Studites zur byzantinischen Hymnographie". Jahrbuch der Österreichischen Byzantinistik 53: 117–125. doi:10.1553/joeb53s117.

External links

- Use of the Eight Tones by St. Kosmas of Maiouma

- "Byzantine Octoechos Chart for those trained in Western Music," Retrieved 2012-01-16

- The Armenian Octoechos Ensemble Akn

- "ΕΛΛΗΝΙΚΑ ΛΕΙΤΟΥΡΓΙΚΑ ΚΕΙΜΕΝΑ ΤΗΣ ΟΡΘΟΔΟΞΗΣ ΕΚΚΛΗΣΙΑΣ — ΟΚΤΩΗΧΟΣ". Retrieved 28 September 2013.

- Archimandrite Ephrem (2008): Vita of Theophanes the Branded and of Joseph the Hymnographer

- Catafygiotu Topping, Eva (1987). "Thekla the Nun: In Praise of Woman". Holy Mothers of Orthodoxy.

- Catafygiotu Topping, Eva (1987). "'Theodosia Melodos'". Holy Mothers of Orthodoxy.

- Catafygiotu Topping, Eva (1987). "Kassiane the Nun and the Sinful Woman". Holy Mothers of Orthodoxy.

Old Slavonic texts of the octoechos and their sources

- "Medieval Slavonic Manuscripts in Macedonia". Skopje: National and University Library "St. Kliment of Ohrid".

- "Digital Library". Sofia: Cyril and Methodius National Library.

- "Ostromir Gospel and the Manuscript Tradition of the New Testament Texts". St Petersburg: National Library of Russia.

- "Department of Manuscripts and Early Printed Books". Moscow: State Historical Museum.

- "Texts from Oktoikh, sirech Osmoglasnik". Moscow: Editions of the Moscow Patriarchate. 1981. Retrieved 24 August 2012.

English translation of octoechos hymns for orthros and hesperinos

- "Vespers from the Sunday Octoechos, with music, in English," Retrieved 2012-01-19

- "Matins from the Sunday Octoechos, with music, in English," Retrieved 2012-01-19

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||