Octahedron

| Regular Octahedron | |

|---|---|

(Click here for rotating model) | |

| Type | Platonic solid |

| Elements | F = 8, E = 12 V = 6 (χ = 2) |

| Faces by sides | 8{3} |

| Conway notation | O aT |

| Schläfli symbols | {3,4} |

r{3,3} or  | |

| Wythoff symbol | 4 | 2 3 |

| Coxeter diagram | |

| Symmetry | Oh, BC3, [4,3], (*432) |

| Rotation group | O, [4,3]+, (432) |

| References | U05, C17, W2 |

| Properties | Regular convex deltahedron |

| Dihedral angle | 109.47122° = arccos(-1/3) |

3.3.3.3 (Vertex figure) |

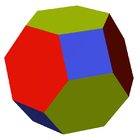

Cube (dual polyhedron) |

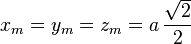

Net | |

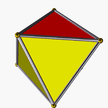

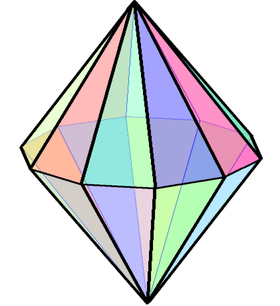

In geometry, an octahedron (plural: octahedra) is a polyhedron with eight faces. A regular octahedron is a Platonic solid composed of eight equilateral triangles, four of which meet at each vertex.

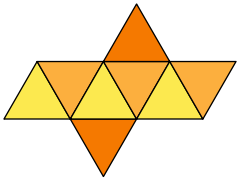

A regular octahedron is the dual polyhedron of a cube. It is a rectified tetrahedron. It is a square bipyramid in any of three orthogonal orientations. It is also a triangular antiprism in any of four orientations.

An octahedron is the three-dimensional case of the more general concept of a cross polytope.

Regular octahedron

Dimensions

If the edge length of a regular octahedron is a, the radius of a circumscribed sphere (one that touches the octahedron at all vertices) is

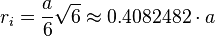

and the radius of an inscribed sphere (tangent to each of the octahedron's faces) is

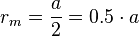

while the midradius, which touches the middle of each edge, is

Orthogonal projections

The octahedron has four special orthogonal projections, centered, on an edge, vertex, face, and normal to a face. The second and third correspond to the B2 and A2 Coxeter planes.

| Centered by | Edge | Face Normal |

Vertex | Face |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Image |  |

|

|

|

| Projective symmetry |

[2] | [2] | [4] | [6] |

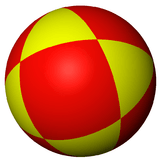

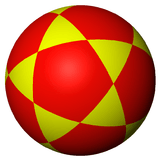

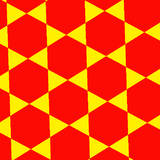

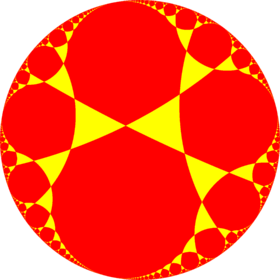

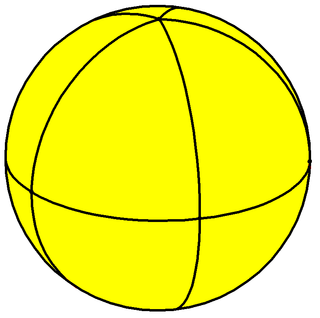

Spherical tiling

The octahedron can also be represented as a spherical tiling, and projected onto the plane via a stereographic projection. This projection is conformal, preserving angles but not areas or lengths. Straight lines on the sphere are projected as circular arcs on the plane.

|

Triangle-centered |

| Orthographic projection | Stereographic projection |

|---|

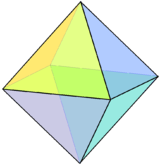

Cartesian coordinates

An octahedron with edge length sqrt(2) can be placed with its center at the origin and its vertices on the coordinate axes; the Cartesian coordinates of the vertices are then

- ( ±1, 0, 0 );

- ( 0, ±1, 0 );

- ( 0, 0, ±1 ).

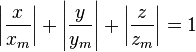

In an x–y–z Cartesian coordinate system, the octahedron with center coordinates (a, b, c) and radius r is the set of all points (x, y, z) such that

Area and volume

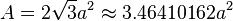

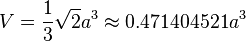

The surface area A and the volume V of a regular octahedron of edge length a are:

Thus the volume is four times that of a regular tetrahedron with the same edge length, while the surface area is twice (because we have 8 vs. 4 triangles).

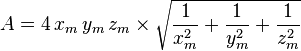

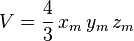

If an octahedron has been stretched so that it obeys the equation:

The formula for the surface area and volume expand to become:

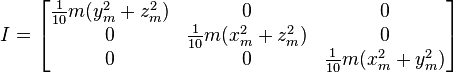

Additionally the inertia tensor of the stretched octahedron is:

These reduce to the equations for the regular octahedron when:

Geometric relations

The interior of the compound of two dual tetrahedra is an octahedron, and this compound, called the stella octangula, is its first and only stellation. Correspondingly, a regular octahedron is the result of cutting off from a regular tetrahedron, four regular tetrahedra of half the linear size (i.e. rectifying the tetrahedron). The vertices of the octahedron lie at the midpoints of the edges of the tetrahedron, and in this sense it relates to the tetrahedron in the same way that the cuboctahedron and icosidodecahedron relate to the other Platonic solids. One can also divide the edges of an octahedron in the ratio of the golden mean to define the vertices of an icosahedron. This is done by first placing vectors along the octahedron's edges such that each face is bounded by a cycle, then similarly partitioning each edge into the golden mean along the direction of its vector. There are five octahedra that define any given icosahedron in this fashion, and together they define a regular compound.

Octahedra and tetrahedra can be alternated to form a vertex, edge, and face-uniform tessellation of space, called the octet truss by Buckminster Fuller. This is the only such tiling save the regular tessellation of cubes, and is one of the 28 convex uniform honeycombs. Another is a tessellation of octahedra and cuboctahedra.

The octahedron is unique among the Platonic solids in having an even number of faces meeting at each vertex. Consequently, it is the only member of that group to possess mirror planes that do not pass through any of the faces.

Using the standard nomenclature for Johnson solids, an octahedron would be called a square bipyramid. Truncation of two opposite vertices results in a square bifrustum.

The octahedron is 4-connected, meaning that it takes the removal of four vertices to disconnect the remaining vertices. It is one of only four 4-connected simplicial well-covered polyhedra, meaning that all of the maximal independent sets of its vertices have the same size. The other three polyhedra with this property are the pentagonal dipyramid, the snub disphenoid, and an irregular polyhedron with 12 vertices and 20 triangular faces.[1]

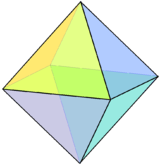

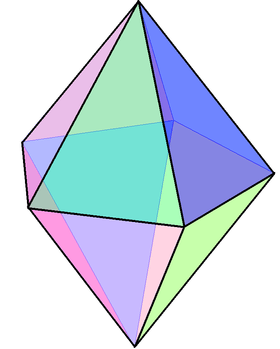

Uniform colorings and symmetry

There are 3 uniform colorings of the octahedron, named by the triangular face colors going around each vertex: 1212, 1112, 1111.

The octahedron's symmetry group is Oh, of order 48, the three dimensional hyperoctahedral group. This group's subgroups include D3d (order 12), the symmetry group of a triangular antiprism; D4h (order 16), the symmetry group of a square bipyramid; and Td (order 24), the symmetry group of a rectified tetrahedron. These symmetries can be emphasized by different colorings of the faces.

| Name | Octahedron | Rectified tetrahedron (Tetratetrahedron) |

Triangular antiprism | Square bipyramid | Rhombic fusil |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Image (Face coloring) |

(1111) |

(1212) |

(1112) |

(1111) |

|

| Coxeter diagram | |||||

| Schläfli symbol | {3,4} | r{3,3} | s{2,6} sr{2,3} |

ft{2,4} { } + {4} |

ftr{2,2} { } + { } + { } |

| Wythoff symbol | 4 | 3 2 | 2 | 4 3 | 2 | 6 2 | 2 3 2 |

||

| Symmetry | Oh, [4,3], (*432) | Td, [3,3], (*332) | D3d, [2+,6], (2*3) D3, [2,3]+, (322) |

D4h, [2,4], (*422) | D2h, [2,2], (*222) |

| Order | 48 | 24 | 12 6 |

16 | 8 |

Nets

It has eleven arrangements of nets.

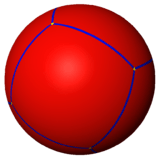

Dual

The octahedron is the dual polyhedron to the cube.

Faceting

The uniform tetrahemihexahedron is a tetrahedral symmetry faceting of the regular octahedron, sharing edge and vertex arrangement. It has four of the triangular faces, and 3 central squares.

Octahedron |

Tetrahemihexahedron |

Irregular octahedra

The following polyhedra are combinatorially equivalent to the regular polyhedron. They all have six vertices, eight triangular faces, and twelve edges that correspond one-for-one with the features of a regular octahedron.

- Triangular antiprisms: Two faces are equilateral, lie on parallel planes, and have a common axis of symmetry. The other six triangles are isosceles.

- Tetragonal bipyramids, in which at least one of the equatorial quadrilaterals lies on a plane. The regular octahedron is a special case in which all three quadrilaterals are planar squares.

- Schönhardt polyhedron, a nonconvex polyhedron that cannot be partitioned into tetrahedra without introducing new vertices.

Other convex octahedra

More generally, an octahedron can be any polyhedron with eight faces. The regular octahedron has 6 vertices and 12 edges, the minimum for an octahedron; irregular octahedra may have as many as 12 vertices and 18 edges.[2] There are 257 topologically distinct convex octahedra, excluding mirror images. More specifically there are 2, 11, 42, 74, 76, 38, 14 for octahedra with 6 to 12 vertices respectively.[3][4] (Two polyhedra are "topologically distinct" if they have intrinsically different arrangements of faces and vertices, such that it is impossible to distort one into the other simply by changing the lengths of edges or the angles between edges or faces.)

Some better known irregular octahedra include the following:

- Hexagonal prism: Two faces are parallel regular hexagons; six squares link corresponding pairs of hexagon edges.

- Heptagonal pyramid: One face is a heptagon (usually regular), and the remaining seven faces are triangles (usually isosceles). It is not possible for all triangular faces to be equilateral.

- Truncated tetrahedron: The four faces from the tetrahedron are truncated to become regular hexagons, and there are four more equilateral triangle faces where each tetrahedron vertex was truncated.

- Tetragonal trapezohedron: The eight faces are congruent kites.

Octahedra in the physical world

Octahedra in nature

- Natural crystals of diamond, alum or fluorite are commonly octahedral, as the space-filling tetrahedral-octahedral honeycomb.

- The plates of kamacite alloy in octahedrite meteorites are arranged paralleling the eight faces of an octahedron.

- Many metal ions coordinate six ligands in an octahedral or distorted octahedral configuration.

- Widmanstätten patterns in nickel-iron crystals

Octahedra in art and culture

- Especially in roleplaying games, this solid is known as a "d8", one of the more common non-cubical dice.

- If each edge of an octahedron is replaced by a one ohm resistor, the resistance between opposite vertices is 1/2 ohms, and that between adjacent vertices 5/12 ohms.[5]

- Six musical notes can be arranged on the vertices of an octahedron in such a way that each edge represents a consonant dyad and each face represents a consonant triad; see hexany.

Tetrahedral Truss

A framework of repeating tetrahedrons and octahedrons was invented by Buckminster Fuller in the 1950s, known as a space frame, commonly regarded as the strongest structure for resisting cantilever stresses.

Related polyhedra

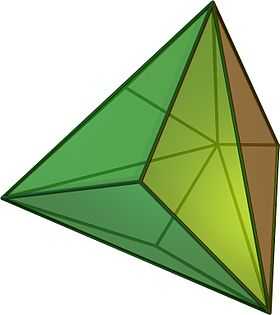

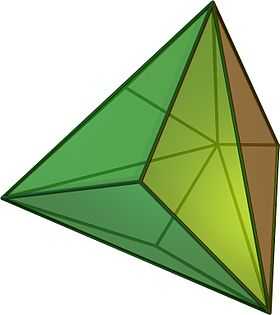

A regular octahedron can be augmented into a tetrahedron by adding 4 tetrahedra on alternated faces. Adding tetrahedra to all 8 faces creates the stellated octahedron.

|

|

| tetrahedron | stellated octahedron |

|---|

The octahedron is one of a family of uniform polyhedra related to the cube.

| Symmetry: [4,3], (*432) | [4,3]+ (432) |

[1+,4,3] = [3,3] (*332) |

[3+,4] (3*2) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| {4,3} | t{4,3} | r{4,3} r{31,1} |

t{3,4} t{31,1} |

{3,4} {31,1} |

rr{4,3} s2{3,4} |

tr{4,3} | sr{4,3} | h{4,3} {3,3} |

h2{4,3} t{3,3} |

s{3,4} s{31,1} |

= |

= |

= |

||||||||

| Duals to uniform polyhedra | ||||||||||

| V43 | V3.82 | V(3.4)2 | V4.62 | V34 | V3.43 | V4.6.8 | V34.4 | V33 | V3.62 | V35 |

It is also one of the simplest examples of a hypersimplex, a polytope formed by certain intersections of a hypercube with a hyperplane.

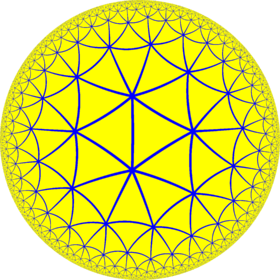

The octahedron is topologically related as a part of sequence of regular polyhedra with Schläfli symbols {3,n}, continuing into the hyperbolic plane.

| Spherical | Euclid. | Compact hyper. | Paraco. | Noncompact hyperbolic | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| {3,2} | {3,3} | {3,4} | {3,5} | {3,6} | {3,7} | {3,8} | (3,∞} | {3,12i} | {3,9i} | {3,6i} | {3,3i} |

Tetratetrahedron

The regular octahedron can also be considered a rectified tetrahedron – and can be called a tetratetrahedron. This can be shown by a 2-color face model. With this coloring, the octahedron has tetrahedral symmetry.

Compare this truncation sequence between a tetrahedron and its dual:

| Symmetry: [3,3], (*332) | [3,3]+, (332) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| {3,3} | t{3,3} | r{3,3} | t{3,3} | {3,3} | rr{3,3} | tr{3,3} | sr{3,3} |

| Duals to uniform polyhedra | |||||||

|

|

|

| ||||

| V3.3.3 | V3.6.6 | V3.3.3.3 | V3.6.6 | V3.3.3 | V3.4.3.4 | V4.6.6 | V3.3.3.3.3 |

The above shapes may also be realized as slices orthogonal to the long diagonal of a tesseract. If this diagonal is oriented vertically with a height of 1, then the first five slices above occur at heights r, 3/8, 1/2, 5/8, and s, where r is any number in the range (0,1/4], and s is any number in the range [3/4,1).

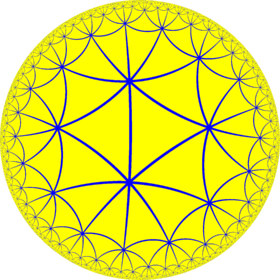

The tetratetrahedron can be seen in a sequence of quasiregular polyhedrons and tilings:

| Sym. *n32 [n,3] |

Spherical | Euclid. | Compact hyperb. | Paraco. | Noncompact hyperbolic | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| *332 [3,3] Td |

*432 [4,3] Oh |

*532 [5,3] Ih |

*632 [6,3] p6m |

*732 [7,3] |

*832 [8,3]... |

*∞32 [∞,3] |

[12i,3] | [9i,3] | [6i,3] | [3i,3] | ||

| Figure |  |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

| Config. | r{3,3} | r{4,3} | r{5,3} | r{6,3} | r{7,3} | r{8,3} | r{∞,3} | r{12i,3} | r{9i,3} | r{6i,3} | r{3i,3} | |

| Coxeter | ||||||||||||

| Dual uniform figures | ||||||||||||

| Dual conf. |

V(3.3)2 |

V(3.4)2 |

V(3.5)2 |

V(3.6)2 |

V(3.7)2 |

V(3.8)2 |

V(3.∞)2 |

|||||

| Coxeter | ||||||||||||

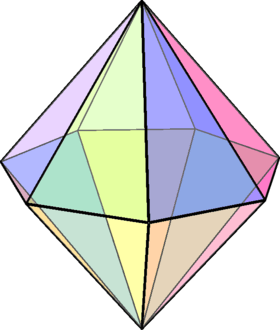

Trigonal antiprism

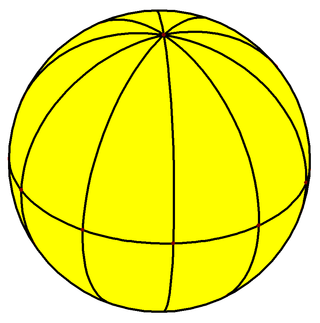

As a trigonal antiprism, the octahedron is related to the hexagonal dihedral symmetry family.

| Symmetry: [6,2], (*622) | [6,2]+, (622) | [1+,6,2], (322) | [6,2+], (2*3) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| {6,2} | t{6,2} | r{6,2} | 2t{6,2}=t{2,6} | 2r{6,2}={2,6} | rr{6,2} | tr{6,2} | sr{6,2} | h{6,2} | s{2,6} |

| Uniform duals | |||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| V62 | V122 | V62 | V4.4.6 | V26 | V4.4.6 | V4.4.12 | V3.3.3.6 | V32 | V3.3.3.3 |

| 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| s{2,4} sr{2,2} |

s{2,6} sr{2,3} |

s{2,8} sr{2,4} |

s{2,10} sr{2,5} |

s{2,12} sr{2,6} |

s{2,14} sr{2,7} |

s{2,16} sr{2,8} |

s{2,18} sr{2,9} |

s{2,20} sr{2,10} |

s{2,22} sr{2,11} |

s{2,24} sr{2,12} |

s{2,2n} sr{2,n} |

| As spherical polyhedra | |||||||||||

Square bipyramid

| 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12... | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

| As spherical polyhedra | ||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||

See also

- Centered octahedral number

- Spinning octahedron

- Stella octangula

- Triakis octahedron

- Hexakis octahedron

- Truncated octahedron

- Octahedral molecular geometry

- Octahedral symmetry

- Octahedral graph

References

- ↑ Finbow, Arthur S.; Hartnell, Bert L.; Nowakowski, Richard J.; Plummer, Michael D. (2010). "On well-covered triangulations. III". Discrete Applied Mathematics 158 (8): 894–912. doi:10.1016/j.dam.2009.08.002. MR 2602814.

- ↑

- ↑ Counting polyhedra

- ↑ http://www.uwgb.edu/dutchs/symmetry/poly8f0.htm

- ↑ Klein, Douglas J. (2002). "Resistance-Distance Sum Rules" (PDF). Croatica Chemica Acta 75 (2): 633–649. Retrieved 2006-09-30.

External links

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Octahedron. |

- Weisstein, Eric W., "Octahedron", MathWorld.

- Richard Klitzing, 3D convex uniform polyhedra, x3o4o - oct

- Editable printable net of an octahedron with interactive 3D view

- Paper model of the octahedron

- K.J.M. MacLean, A Geometric Analysis of the Five Platonic Solids and Other Semi-Regular Polyhedra

- The Uniform Polyhedra

- Virtual Reality Polyhedra The Encyclopedia of Polyhedra

- Conway Notation for Polyhedra Try: dP4

| ||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Fundamental convex regular and uniform polytopes in dimensions 2–10 | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family | An | Bn | I2(p) / Dn | E6 / E7 / E8 / F4 / G2 | Hn | |||||||

| Regular polygon | Triangle | Square | p-gon | Hexagon | Pentagon | |||||||

| Uniform polyhedron | Tetrahedron | Octahedron • Cube | Demicube | Dodecahedron • Icosahedron | ||||||||

| Uniform 4-polytope | 5-cell | 16-cell • Tesseract | Demitesseract | 24-cell | 120-cell • 600-cell | |||||||

| Uniform 5-polytope | 5-simplex | 5-orthoplex • 5-cube | 5-demicube | |||||||||

| Uniform 6-polytope | 6-simplex | 6-orthoplex • 6-cube | 6-demicube | 122 • 221 | ||||||||

| Uniform 7-polytope | 7-simplex | 7-orthoplex • 7-cube | 7-demicube | 132 • 231 • 321 | ||||||||

| Uniform 8-polytope | 8-simplex | 8-orthoplex • 8-cube | 8-demicube | 142 • 241 • 421 | ||||||||

| Uniform 9-polytope | 9-simplex | 9-orthoplex • 9-cube | 9-demicube | |||||||||

| Uniform 10-polytope | 10-simplex | 10-orthoplex • 10-cube | 10-demicube | |||||||||

| Uniform n-polytope | n-simplex | n-orthoplex • n-cube | n-demicube | 1k2 • 2k1 • k21 | n-pentagonal polytope | |||||||

| Topics: Polytope families • Regular polytope • List of regular polytopes | ||||||||||||