Objet d'art

Objet d'art (plural objets d'art) means literally "art object", or work of art, in French, but in practice the term has long been reserved to describe works of art that are not paintings, large or medium sized sculptures, prints or drawings. It therefore covers a wide range of works, usually small and three-dimensional, of high quality and finish in areas of the decorative arts, such as metalwork items, with or without enamel, small carvings, statuettes and plaquettes in any material, including engraved gems, hardstone carvings, ivory carvings including Japanese netsuke and similar items, non-utilitarian porcelain and glass, and a vast range of objects that would also be classed as antiques (or indeed antiquities), such as small clocks, watches, gold boxes, and sometimes textiles, especially tapestries. Books with fine bookbindings might be included.

The term is somewhat flexible, and is often used as a broad term for "everything else" after major categories have been dealt with. Thus the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich, London describes its collection as follows: "The National Maritime Museum's collection of objet d’art comprises over 800 objects. These are mostly small decorative art items that fall outside the scope of the Museum’s ceramic, plate, textiles and glass collections." The items illustrated on their website (all with maritime associations) include metal curtain ties, a "lacquered papier-maché tray", tapestries, small boxes for tobacco, snuff, cosmetics and other purposes, cut-paper pictures (découpage), small silver items, miniature paintings, a "Gilt-brass clock finial", ceramic plaques, statuettes, cigarette boxes, plaquettes, a painted tray, a horse brass, a metal "pipe tamper", a small glass painting, a fan, a handle plate from furniture, and various other items.[1]

The term is used with the same meaning in French, but in that language it may sometimes be a synonym for "work of art", and has retained more respectability in the worlds of art history and museums than in English, where in recent decades it is often avoided (even more in archaeology), but remains in use in the world of collecting and the art and antique markets. In English it may be italicised as a foreign word, or not; either may be considered correct. Incorrect forms such as "objet-d'art", "object(s) d'art" are sometimes seen,[2] and the term should not be capitalized in running prose.

Objet de vertu

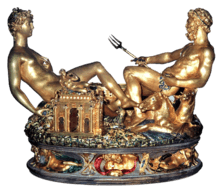

An arguably more precious variant is objet de vertu (usually italicised), in which vertu is intended to suggest rich materials and a higher standard of refined facture and finish, and would typically exclude objects with a practical function, being restricted to "collector's pieces" that are purely decorative. Objets de vertu reflect the rarified aesthetic and conspicuous consumption characteristic of court art, whether of the late-medieval Burgundian dukes, the Mughal emperors, or Ming and later imperial China. Examples could be adduced from Antiquity as well,[3] whilst the pre-World War I production of Peter Carl Fabergé, epitomized by the famous Fabergé eggs, made in the style of genuine Easter eggs, but using precious metals and gemstones rather than more mundane materials, are late examples of objets de vertu.

A comparable term that appears in 18th- and 19th-century French sale catalogs,[4] though now less used, is objets de curiosité, "objects of curiosity",[5] now devolved into the less-valued curio.

References

- ↑ objets d'art, National Maritime Museum

- ↑ Indeed, 19th century wills and inventories of the Rothschild family include many "Objects d'art" and "objects of virtue".

- ↑ The Lycurgus Cup, a Roman glass cage cup now in the British Museum, the Byzantine agate "Rubens vase", among many objets d'art in the Walters Art Gallery, the Roman glass "Portland Vase" and many ancient onyx or sard cameos, for instances.

- ↑ Such as the Catalogue raisonné des différens objets de curiosité dans les sciences et arts, qui composoient le cabinet de feu Mr.. Paris, 1775; in 1916 A. Tuete edited the Inventaire des laques anciennes et des objets de curiosité de Marie-Antoinette: confiés à Daguerre et Lignereux, marchands bijoutiers, le 10 octobre 1789.

- ↑ Maurice Rheims' La vie étrange des objets (1959) is subtitled histoire de la curiosité.