Nylon

Nylon 6,6 Nylon 6,6  | |

|---|---|

| Density | 1.15 g/cm3 |

| Electrical conductivity (σ) | 10−12 S/m |

| Thermal conductivity | 0.25 W/(m·K) |

| Melting point | 463–624 K 190–350 °C 374–663 °F |

Nylon is a generic designation for a family of synthetic polymers, more specifically aliphatic or semi-aromatic polyamides. They can be melt processed into fibres, films or shapes.[1] The first example of nylon (nylon 66) was produced on February 28, 1935, by Wallace Carothers at DuPont's research facility at the DuPont Experimental Station.[2][3] Nylon polymers have found significant commercial applications in fibres (apparel, flooring and rubber reinforcement), in shapes (moulded parts for cars, electrical equipment, etc.), and in films (mostly for food packaging)[4]

Overview

Nylon is a thermoplastic,[5] silky material, first used commercially in a nylon-bristled toothbrush (1938), followed more famously by women's stockings ("nylons"; 1940) after being introduced as a fabric at the 1939 New York World's Fair.[6] Nylon is made of repeating units linked by amide bonds and is frequently referred to as polyamide (PA).[7][8] Nylon was the first commercially successful synthetic thermoplastic polymer.[7] There are two common ways of making nylon for fiber applications. In one approach, molecules with an acid (-COOH) group on each end are reacted with molecules containing amine (-NH2) groups on each end. The resulting nylon is named on the basis of the number of carbon atoms separating the two acid groups and the two amines. These are formed into monomers of intermediate molecular weight, which are then reacted to form long polymer chains.[7]

Nylon was intended to be a synthetic replacement for silk and substituted for it in many different products after silk became scarce during World War II. It replaced silk in military applications such as parachutes and flak vests, and was used in many types of vehicle tires.[6]

Nylon fibers are used in many applications, including clothes fabrics, bridal veils, package paper, carpets, musical strings, pipes, tents, and rope.

Solid nylon is used in hair combs and mechanical parts such as machine screws, gears and other low- to medium-stress components previously cast in metal.[9] Engineering-grade nylon is processed by extrusion, casting, and injection molding. Type 6,6 Nylon 101 is the most common commercial grade of nylon, and Nylon 6 is the most common commercial grade of molded nylon.[10] For use in tools such as spudgers, nylon is available in glass-filled variants which increase structural and impact strength and rigidity, and molybdenum sulfide-filled variants which increase lubricity. Its various properties also make it very useful as a material in additive manufacturing; specifically as a filament in consumer and professional grade fused deposition modeling 3D printers.[11]

Chemistry

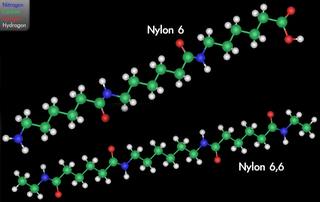

Nylons are condensation copolymers formed by reacting equal parts of a diamine and a dicarboxylic acid, so that amides are formed at both ends of each monomer in a process analogous to polypeptide biopolymers. Chemical elements included are carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen, and oxygen. The numerical suffix specifies the numbers of carbons donated by the monomers; the diamine first and the diacid second. The most common variant is nylon 6-6, which refers to the fact that the diamine (hexamethylene diamine, IUPAC name: hexane-1,6-diamine) and the diacid (adipic acid, IUPAC name: hexanedioic acid) each donate 6 carbons to the polymer chain. As with other regular copolymers like polyesters and polyurethanes, the "repeating unit" consists of one of each monomer, so that they alternate in the chain. Since each monomer in this copolymer has the same reactive group on both ends, the direction of the amide bond reverses between each monomer, unlike natural polyamide proteins, which have overall directionality: C terminal → N terminal. In the laboratory, nylon 6-6 can also be made using adipoyl chloride instead of adipic acid.

It is difficult to get the proportions exactly correct, and deviations can lead to chain termination at molecular weights less than a desirable 10,000 daltons (u). To overcome this problem, a crystalline, solid "nylon salt" can be formed at room temperature, using an exact 1:1 ratio of the acid and the base to neutralize each other. Heated to 285 °C (545 °F), the salt reacts to form nylon polymer. Above 20,000 daltons, it is impossible to spin the chains into yarn, so to combat this, some acetic acid is added to react with a free amine end group during polymer elongation to limit the molecular weight. In practice, and especially for 6,6, the monomers are often combined in a water solution. The water used to make the solution is evaporated under controlled conditions, and the increasing concentration of "salt" is polymerized to the final molecular weight.

DuPont patented[12] nylon 6,6, so in order to compete, other companies (particularly the German BASF) developed the homopolymer nylon 6, or polycaprolactam — not a condensation polymer, but formed by a ring-opening polymerization (alternatively made by polymerizing aminocaproic acid). The peptide bond within the caprolactam is broken with the exposed active groups on each side being incorporated into two new bonds as the monomer becomes part of the polymer backbone. In this case, all amide bonds lie in the same direction, but the properties of nylon 6 are sometimes indistinguishable from those of nylon 6,6 — except for melt temperature and some fiber properties in products like carpets and textiles. There is also nylon 9.

The 428 °F (220 °C) melting point of nylon 6 is lower than the 509 °F (265 °C) melting point of nylon 6,6.[13]

Nylon 5,10, made from pentamethylene diamine and sebacic acid, was studied by Carothers even before nylon 6,6 and has superior properties, but is more expensive to make. In keeping with this naming convention, "nylon 6,12" (N-6,12) or "PA-6,12" is a copolymer of a 6C diamine and a 12C diacid. Similarly for N-5,10 N-6,11; N-10,12, etc. Other nylons include copolymerized dicarboxylic acid/diamine products that are not based upon the monomers listed above. For example, some aromatic nylons are polymerized with the addition of diacids like terephthalic acid (→ Kevlar, Twaron) or isophthalic acid (→ Nomex), more commonly associated with polyesters. There are copolymers of N-6,6/N6; copolymers of N-6,6/N-6/N-12; and others. Because of the way polyamides are formed, nylon would seem to be limited to unbranched, straight chains. But "star" branched nylon can be produced by the condensation of dicarboxylic acids with polyamines having three or more amino groups.

The general reaction is:

Two molecules of water are given off and the nylon is formed. Its properties are determined by the R and R' groups in the monomers. In nylon 6,6, R = 4C and R' = 6C alkanes, but one also has to include the two carboxyl carbons in the diacid to get the number it donates to the chain. In Kevlar, both R and R' are benzene rings.

Concepts of nylon production

The first approach: combining molecules with an acid (COOH) group on each end are reacted with two chemicals that contain amine (NH2) groups on each end. This process creates nylon 6,6, made of hexamethylene diamine with six carbon atoms and adipic acid.

The second approach: a compound has an acid at one end and an amine at the other and is polymerized to form a chain with repeating units of (-NH-[CH2]n-CO-)x. In other words, nylon 6 is made from a single six-carbon substance called caprolactam. In this equation, if n = 5, then nylon 6 is the assigned name (may also be referred to as polymer).

The characteristic features of nylon 6,6 include:

- Pleats and creases can be heat-set at higher temperatures

- More compact molecular structure

- Better weathering properties; better sunlight resistance

- Softer "Hand"

- Higher melting point (256 °C/492.8 °F)

- Superior colorfastness

- Excellent abrasion resistance

On the other hand, nylon 6 is easy to dye, more readily fades; it has a higher impact resistance, a more rapid moisture absorption, greater elasticity and elastic recovery.

Characteristics

- Variation of luster: nylon has the ability to be very lustrous, semilustrous or dull.

- Durability: its high tenacity fibers are used for seatbelts, tire cords, ballistic cloth and other uses.

- High elongation

- Excellent abrasion resistance

- Highly resilient (nylon fabrics are heat-set)

- Paved the way for easy-care garments

- High resistance to insects, fungi, animals, as well as molds, mildew, rot and many chemicals

- Used in carpets and nylon stockings

- Melts instead of burning

- Used in many military applications

- Good specific strength

- Transparent to infrared light (−12 dB)[14]

Bulk properties

Above their melting temperatures, Tm, thermoplastics like nylon are amorphous solids or viscous fluids in which the chains approximate random coils. Below Tm, amorphous regions alternate with regions which are lamellar crystals.[15] The amorphous regions contribute elasticity and the crystalline regions contribute strength and rigidity. The planar amide (-CO-NH-) groups are very polar, so nylon forms multiple hydrogen bonds among adjacent strands. Because the nylon backbone is so regular and symmetrical, especially if all the amide bonds are in the trans configuration, nylons often have high crystallinity and make excellent fibers. The amount of crystallinity depends on the details of formation, as well as on the kind of nylon. Apparently it can never be quenched from a melt as a completely amorphous solid.

Nylon 6,6 can have multiple parallel strands aligned with their neighboring peptide bonds at coordinated separations of exactly 6 and 4 carbons for considerable lengths, so the carbonyl oxygens and amide hydrogens can line up to form interchain hydrogen bonds repeatedly, without interruption (see the figure opposite). Nylon 5,10 can have coordinated runs of 5 and 8 carbons. Thus parallel (but not antiparallel) strands can participate in extended, unbroken, multi-chain β-pleated sheets, a strong and tough supermolecular structure similar to that found in natural silk fibroin and the β-keratins in feathers. (Proteins have only an amino acid α-carbon separating sequential -CO-NH- groups.) Nylon 6 will form uninterrupted H-bonded sheets with mixed directionalities, but the β-sheet wrinkling is somewhat different. The three-dimensional disposition of each alkane hydrocarbon chain depends on rotations about the 109.47° tetrahedral bonds of singly bonded carbon atoms.

When extruded into fibers through pores in an industrial spinneret, the individual polymer chains tend to align because of viscous flow. If subjected to cold drawing afterwards, the fibers align further, increasing their crystallinity, and the material acquires additional tensile strength. In practice, nylon fibers are most often drawn using heated rolls at high speeds.[16]

Block nylon tends to be less crystalline, except near the surfaces due to shearing stresses during formation. Nylon is clear and colorless, or milky, but is easily dyed. Multistranded nylon cord and rope is slippery and tends to unravel. The ends can be melted and fused with a heat source such as a flame or electrode to prevent this.

When dry, polyamide is a good electrical insulator. However, polyamide is hygroscopic. The absorption of water will change some of the material's properties such as its electrical resistance. Nylon is less absorbent than wool or cotton.

Uses

Fibres

Bill Pittendreigh, DuPont, and other individuals and corporations worked diligently during the first few months of World War II to find a way to replace Asian silk and hemp with nylon in parachutes. It was also used to make tires, tents, ropes, ponchos, and other military supplies. It was even used in the production of a high-grade paper for U.S. currency. At the outset of the war, cotton accounted for more than 80% of all fibers used and manufactured, and wool fibers accounted for nearly all of the rest. By August 1945, manufactured fibers had taken a market share of 25%, at the expense of cotton. After the war, because of shortages of both silk and nylon, nylon parachute material was sometimes repurposed to make dresses.[17]

Nylon 6 and 66 fibres are used in carpet manufacture.

Nylon is one kind of fibre used in tire cord.

Shapes

Nylon resins are widely used in the automobile industry especially in the engine compartment.[18][19]

Nylon can be used as the matrix material in composite materials, with reinforcing fibers like glass or carbon fiber; such a composite has a higher density than pure nylon.[20] Such thermoplastic composites (25% to 30% glass fiber) are frequently used in car components next to the engine, such as intake manifolds, where the good heat resistance of such materials makes them feasible competitors to metals.[21]

Nylon was used to make the stock of the Remington Nylon 66 rifle.[22] The frame of the modern Glock pistol is made of a nylon composite.[23]

Food packaging

Nylon resins are used as a component of food packaging films where an oxygen barrier is needed.[4] Some of the terpolymers based upon nylon are used every day in packaging. Nylon has been used for meat wrappings and sausage sheaths.[24] The high temperature resistance of nylon makes it useful for oven bags[25]

Filaments

Nylon filaments are primarily used in brushes especially toothbrushes and 'strimmers'. They are also used as monofilaments in fishing line.

Its various properties also make it very useful as a material in additive manufacturing; specifically as a filament in consumer and professional grade fused deposition modeling 3D printers.[11]

Other forms

Extruded Profiles

Nylon resins can be extruded into rods, tubes and sheets.[26] [27]

Powder Coating

Nylon powders are used to power coat metals. Nylon 11 and nylon 12 are the most widely used.[28]

Instrument strings

In the mid-1940s, classical guitarist Andrés Segovia mentioned the shortage of good guitar strings in the United States, particularly his favorite Pirastro catgut strings, to a number of foreign diplomats at a party, including General Lindeman of the British Embassy. A month later, the General presented Segovia with some nylon strings which he had obtained via some members of the DuPont family. Segovia found that although the strings produced a clear sound, they had a faint metallic timbre which he hoped could be eliminated.[29]

Nylon strings were first tried on stage by Olga Coelho in New York in January, 1944.[30]

In 1946, Segovia and string maker Albert Augustine were introduced by their mutual friend Vladimir Bobri, editor of Guitar Review. On the basis of Segovia's interest and Augustine's past experiments, they decided to pursue the development of nylon strings. DuPont, skeptical of the idea, agreed to supply the nylon if Augustine would endeavor to develop and produce the actual strings. After three years of development, Augustine demonstrated a nylon first string whose quality impressed guitarists, including Segovia, in addition to DuPont.[29]

Wound strings, however, were more problematic. Eventually, however, after experimenting with various types of metal and smoothing and polishing techniques, Augustine was also able to produce high quality nylon wound strings.[29]

Hydrolysis and degradation

All nylons are susceptible to hydrolysis, especially by strong acids, a reaction essentially the reverse of the synthetic reaction shown above. The molecular weight of nylon products so attacked drops fast, and cracks form quickly at the affected zones. Lower members of the nylons (such as nylon 6) are affected more than higher members such as nylon 12. This means that nylon parts cannot be used in contact with sulfuric acid for example, such as the electrolyte used in lead–acid batteries. When being molded, nylon must be dried to prevent hydrolysis in the molding machine barrel since water at high temperatures can also degrade the polymer.[31] The reaction is of the type:

Environmental impact, incineration and recycling

Berners-Lee reckons the average greenhouse gas footprint of nylon in manufacturing carpets at 5.43 kg CO2 equivalent per kilo, when produced in Europe. This gives it almost the same carbon footprint as wool, but with greater durability and therefore a lower overall carbon footprint.[32]

Data published by PlasticsEurope indicates for nylon 66 a greenhouse gas footprint of 6.4 kg CO2 equivalent per kilo, and a energy consumption of 138 kJ/kg.[33] When considering the environmental impact of nylon, it is important to consider the use phase. In particular when cars are lightweighted, significant savings in fuel consumption and CO2 emissions are reduced.

Various nylons break down in fire and form hazardous smoke, and toxic fumes or ash, typically containing hydrogen cyanide. Incinerating nylons to recover the high energy used to create them is usually expensive, so most nylons reach the garbage dumps, decaying very slowly.[34] Nylon is a robust polymer and lends itself well to recycling. Much nylon resin is recycled directly in a closed loop at the injection moulding machine, by grinding sprues and runners and mixing hem with the virgin granules being consumed by the moulding machine.[35]

Etymology

In 1940, John W. Eckelberry of DuPont stated that the letters "nyl" were arbitrary and the "on" was copied from the suffixes of other fibers such as cotton and rayon. A later publication by DuPont (Context, vol. 7, no. 2, 1978) explained that the name was originally intended to be "No-Run" ("run" meaning "unravel"), but was modified to avoid making such an unjustified claim. Since the products were not really run-proof, the vowels were swapped to produce "nuron", which was changed to "nilon" "to make it sound less like a nerve tonic". For clarity in pronunciation, the "i" was changed to "y".[6][36]

An alternative but apocryphal explanation for the name is that it is a combination of New York and London: NY-Lon.

See also

References

- ↑ Kohan, Melvin (1995). Nylon Plastics Handbook. Munich: Carl Hanser Verlag. p. 2. ISBN 1569901899.

- ↑ American Chemical Society National Historic Chemical Landmarks. "Foundations of Polymer Science: Wallace Carothers and the Development of Nylon". ACS Chemistry for Life. Retrieved 27 January 2015.

- ↑ "Wallace Hume Carothers". Chemical Heritage Foundation. Retrieved 27 January 2015.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 "Materials/Polyamide". PAFA. Packaging and Film Association. Retrieved 19 April 2015.

- ↑ Vogler, H (2013). "Wettstreit um die Polyamidfasern". Chemie in unserer Zeit 47: 62–63. doi:10.1002/ciuz.201390006.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Wolfe, Audra J. (2008). "Nylon: A Revolution in Textiles". Chemical Heritage Magazine 26 (3). Retrieved 27 January 2015.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 "Science of Plastics". Conflicts in Chemistry: The Case of Plastics. Chemical Heritage Foundation. Retrieved 27 January 2015.

- ↑ Clark, Jim. "Polyamides". Chemguide. Retrieved 27 January 2015.

- ↑ Youssef, Helmi A.; El-Hofy,, Hassan A.; Ahmed, Mahmoud H. (2011). Manufacturing technology : materials, processes, and equipment. Boca Raton, FL: Taylor & Francis/CRC Press. p. 350. ISBN 9781439810859. Retrieved 27 January 2015.

- ↑ "Nylon 6/6 – Commercial Grades and Properties". Emco Industrial Plastics, Inc. Retrieved November 17, 2014.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 "Use of Nylon in 3D Printing". http://3dprintingforbeginners.com/''. Retrieved 11 January 2015.

- ↑ History of Nylon US Patent 2,130,523 'Linear polyamides suitable for spinning into strong pliable fibers', U.S. Patent 2,130,947 'Diamine dicarboxylic acid salt' and U.S. Patent 2,130,948 'Synthetic fibers', all issued September 20, 1938

- ↑ Typical physical characteristics of nylon at "Basics of Design Engineering"

- ↑ Bjarnason, J. E.; Chan, T. L. J.; Lee, A. W. M.; Celis, M. A.; Brown, E. R. (2004). "Millimeter-wave, terahertz, and mid-infrared transmission through common clothing". Applied Physics Letters 85 (4): 519. doi:10.1063/1.1771814.

- ↑ Valerie Menzer's Nylon 66 Webpage. Arizona University

- ↑ Campbell, Ian M. (2000). Introduction to synthetic polymers. Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press. ISBN 0198564708.

- ↑ Caruso, David (2009). "Saving the (Wedding) Day: Oral History Spotlight" (PDF). Transmutations Fall (5): 2. Retrieved 24 June 2013.

- ↑ http://www.materialdatacenter.com/mb/main/pdf/application/16449 Nylon Oil Pan

- ↑ Kohan, Melvin (1995). Nylon Plastics Handbook. Munich: Carl Hanser Verlag. p. 514. ISBN 1569901899.

- ↑ "Fiberglass and Composite Material Design Guide". Performance Composites Inc. Retrieved 27 January 2015.

- ↑ Page, I. B. (2000). Polyamides as engineering thermoplastic materials. Shawbury, Shrewsbury: Rapra Technology Ltd. p. 115. ISBN 9781859572207.

- ↑ "How do you take care of a nylon 66 or 77? You don't.". Field & Stream 75 (9). 1971. Retrieved 27 January 2015.

- ↑ Sweeney, Patrick (2013). Glock deconstructed. Iola, Wis.: Krause. p. 92. ISBN 978-1440232787. Retrieved 27 January 2015.

- ↑ Colbert, Judy (2013). It happened in Delaware : remarkable events that shaped history (First edition. ed.). Morris Book Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7627-6968-1. Retrieved 27 January 2015.

- ↑ "Oven Bags". Cooks Info. Retrieved 19 April 2015.

- ↑ Kohan, Melvin (1995). Nylon Plastics Handbook. Munich: Carl Hanser Verlag. p. 209. ISBN 1569901899.

- ↑ "Extruded and Cast Nylons". www.quadrantplastics.com. Quadrant Plastics. Retrieved 19 April 2015.

- ↑ D. S. Richart (1995). "9.1 Powder Coating". In Kohan, Melvin. Nylon Plastics Handbook. Munich: Hanser. p. 253. ISBN 1569901899.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 "The History of Classical guitar strings". Maestros of the Guitar. Retrieved 27 January 2015.

- ↑ Bellow, Alexander (1970). The Illustrated History of the Guitar. New York: Belwin-Mills. p. 193.

- ↑ "Adhesive for nylon & kevlar". Reltek. Retrieved 27 January 2015.

- ↑ Mike Berners-Lee, How Bad are Bananas? The Carbon Footprint of Everything (London: Profile, 2010), p. 112 (table 6.1), http://books.google.is/books?id=zs13m5JquBwC&.

- ↑ Eco-profiles and Environmental Product Declarations of the European Plastics Manufacturers: Polyamide 6.6. Brussels: PlasticsEurope AISBL. 2014.

- ↑ Typically 80 to 100% is sent to landfill or garbage dumps, while less than 18% are incinerated while recovering the energy. See Francesco La Mantia (August 2002). Handbook of plastics recycling. iSmithers Rapra Publishing. pp. 19–. ISBN 978-1-85957-325-9. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ↑ Boydell, P; Bradfield, C; von Falkenhausen, V; Prautzsch, G (1995). "Recycling of Waste from Glass-reinforced nylon resins". Engineering Design 2: 8–10.

- ↑ Algeo, John (2009). The Origins and Development of the English Language 6. Cengage. p. 224. ISBN 9781428231450.

Further reading

- Textiles by Sara J. Kadolph, ISBN 0-13-118769-4

- Kohan, Melvin I. (1995). Nylon Plastics Handbook. Hanser/Gardner Publications. ISBN 9781569901892

External links

For historical perspectives on nylon, see the Documents List of "The Stocking Story: You Be The Historian" at the Smithsonian website, by The Lemelson Center for the Study of Invention and Innovation, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Nylon. |

- A chemical demonstration of the synthesis of nylon in Carleton University's CHEM 1000 course. (Video)

- Typical properties of Nylon / Polyamide

- Polyamide material description

- Discussion of nylon synthesis and properties

- "How Nylon Yarn Is Made", January 1946, Popular Science from raw material to shipment article with drawings and illustrations

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

.svg.png)