Nuclear space

In mathematics, a nuclear space is a topological vector space with many of the good properties of finite-dimensional vector spaces. The topology on them can be defined by a family of seminorms whose unit balls decrease rapidly in size. Vector spaces whose elements are "smooth" in some sense tend to be nuclear spaces; a typical example of a nuclear space is the set of smooth functions on a compact manifold.

All finite-dimensional vector spaces are nuclear (because every operator on a finite-dimensional vector space is nuclear). There are no Banach spaces that are nuclear, except for the finite-dimensional ones. In practice a sort of converse to this is often true: if a "naturally occurring" topological vector space is not a Banach space, then there is a good chance that it is nuclear.

Much of the theory of nuclear spaces was developed by Alexander Grothendieck and published in (Grothendieck 1955).

Definition

This section lists some of the more common definitions of a nuclear space. The definitions below are all equivalent. Note that some authors use a more restrictive definition of a nuclear space, by adding the condition that the space should be Fréchet. (This means that the space is complete and the topology is given by a countable family of seminorms.)

We start by recalling some background. A locally convex topological vector space V has a topology that is defined by some family of seminorms. For any seminorm, the unit ball is a closed convex symmetric neighborhood of 0, and conversely any closed convex symmetric neighborhood of 0 is the unit ball of some seminorm. (For complex vector spaces, the condition "symmetric" should be replaced by "balanced".) If p is a seminorm on V, we write Vp for the Banach space given by completing V using the seminorm p. There is a natural map from V to Vp (not necessarily injective).

If q is another seminorm, larger than p, then there is a natural map from Vq to Vp such that the first map factors as V → Vq → Vp. These maps are always continuous. The space V is nuclear when a stronger condition holds, namely that these maps are nuclear operators. The condition of being a nuclear operator is subtle, and more details are available in the corresponding article.

Definition 1: A nuclear space is a locally convex topological vector space such that for any seminorm p we can find a larger seminorm q so that the natural map from Vq to Vp is nuclear.

Informally, this means that whenever we are given the unit ball of some seminorm, we can find a "much smaller" unit ball of another seminorm inside it, or that any neighborhood of 0 contains a "much smaller" neighborhood. It is not necessary to check this condition for all seminorms p; it is sufficient to check it for a set of seminorms that generate the topology, in other words, a set of seminorms that are a subbase for the topology.

Instead of using arbitrary Banach spaces and nuclear operators, we can give a definition in terms of Hilbert spaces and trace class operators, which are easier to understand. (On Hilbert spaces nuclear operators are often called trace class operators.) We will say that a seminorm p is a Hilbert seminorm if Vp is a Hilbert space, or equivalently if p comes from a sesquilinear positive semidefinite form on V.

Definition 2: A nuclear space is a topological vector space with a topology defined by a family of Hilbert seminorms, such that for any Hilbert seminorm p we can find a larger Hilbert seminorm q so that the natural map from Vq to Vp is trace class.

Some authors prefer to use Hilbert–Schmidt operators rather than trace class operators. This makes little difference, because any trace class operator is Hilbert–Schmidt, and the product of two Hilbert–Schmidt operators is of trace class.

Definition 3: A nuclear space is a topological vector space with a topology defined by a family of Hilbert seminorms, such that for any Hilbert seminorm p we can find a larger Hilbert seminorm q so that the natural map from Vq to Vp is Hilbert–Schmidt.

If we are willing to use the concept of a nuclear operator from an arbitrary locally convex topological vector space to a Banach space, we can give shorter definitions as follows:

Definition 4: A nuclear space is a locally convex topological vector space such that for any seminorm p the natural map from V to Vp is nuclear.

Definition 5: A nuclear space is a locally convex topological vector space such that any continuous linear map to a Banach space is nuclear.

Grothendieck used a definition similar to the following one:

Definition 6: A nuclear space is a locally convex topological vector space A such that for any locally convex topological vector space B the natural map from the projective to the injective tensor product of A and B is an isomorphism.

In fact it is sufficient to check this just for Banach spaces B, or even just for the single Banach space l1 of absolutely convergent series.

Examples

- A simple infinite dimensional example of a nuclear space is the space of all rapidly decreasing sequences c=(c1, c2,...). ("Rapidly decreasing" means that cnp(n) is bounded for any polynomial p.) For each real number s, we can define a norm ||·||s by

- ||c||s = sup |cn|ns

If the completion in this norm is Cs, then there is a natural map from Cs to Ct whenever s≥t, and this is nuclear whenever s>t+1, essentially because the series Σnt−s is then absolutely convergent. In particular for each norm ||·||t we can find another norm, say ||·||t+2, such that the map from Ct+2 to Ct is nuclear. So the space is nuclear.

- The space of smooth functions on any compact manifold is nuclear.

- The Schwartz space of smooth functions on

for which the derivatives of all orders are rapidly decreasing is a nuclear space.

for which the derivatives of all orders are rapidly decreasing is a nuclear space.

- The space of entire holomorphic functions on the complex plane is nuclear.

- The inductive limit of a sequence of nuclear spaces is nuclear.

- The strong dual of a nuclear Fréchet space is nuclear.

- The product of a family of nuclear spaces is nuclear.

- The completion of a nuclear space is nuclear (and in fact a space is nuclear if and only if its completion is nuclear).

- The tensor product of two nuclear spaces is nuclear.

Properties

Nuclear spaces are in many ways similar to finite-dimensional spaces and have many of their good properties.

- A locally convex Hausdorff space is nuclear if and only if its completion is nuclear.

- A Frechet space is nuclear if and only if its strong dual is nuclear.

- Every bounded subset of a nuclear space is precompact (recall that a set is precompact if its closure in the completion of the space is compact).

- If X is a quasi-complete (i.e. all closed and bounded subsets are complete) nuclear space then X has the Heine-Borel property (that is, every closed and bounded subset of X is compact).

- A nuclear quasi-complete barrelled space is a Montel space.

- Every closed equicontinuous subsets of the dual of a nuclear space is a compact metrizable set (for the strong dual topology).

- Every nuclear space is a subspace of a product of Hilbert spaces.

- Every nuclear space admits a basis of seminorms consisting of Hilbert norms.

- Every nuclear space is a Schwartz space.

- Every nuclear space possesses the approximation property.[1]

- A closed bounded subset of a nuclear Fréchet space is compact. (A bounded subset B of a topological vector space is one such that for any neighborhood U of 0 we can find a positive real scalar λ such that B is contained in λU.) This statement may be paraphrased as a Heine–Borel theorem for nuclear Fréchet spaces, analogous to the finite-dimensional situation.

- Any subspace and any quotient space by a closed subspace of a nuclear space is nuclear.

- If A is nuclear and B is any locally convex topological vector space, then the natural map from the projective tensor product of A and B to the injective tensor product is an isomorphism. Roughly speaking this means that there is only one sensible way to define the tensor product. This property characterizes nuclear spaces A.

- In the theory of measures on topological vector spaces, a basic theorem states that any continuous cylinder set measure on the dual of a nuclear Fréchet space automatically extends to a Radon measure. This is useful because it is often easy to construct cylinder set measures on topological vector spaces, but these are not good enough for most applications unless they are Radon measures (for example, they are not even countably additive in general).

Bochner–Minlos theorem

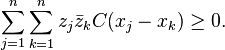

A continuous functional C on a nuclear space A is called a characteristic functional if C(0) = 1, and for any complex  and

and  , j,k = 1, ..., n,

, j,k = 1, ..., n,

Given a characteristic functional on a nuclear space A, the Bochner–Minlos theorem (after Salomon Bochner and Robert Adol'fovich Minlos) guarantees the existence and uniqueness of the corresponding probability measure  on the dual space

on the dual space  , given by

, given by

This extends the inverse Fourier transform to nuclear spaces.

In particular, if A is the nuclear space

,

,

where  are Hilbert spaces, the Bochner–Minlos theorem guarantees the existence of a probability measure with the characteristic function

are Hilbert spaces, the Bochner–Minlos theorem guarantees the existence of a probability measure with the characteristic function  , that is, the existence of the Gaussian measure on the dual space. Such measure is called white noise measure. When A is the Schwartz space, the corresponding random element is a random distribution.

, that is, the existence of the Gaussian measure on the dual space. Such measure is called white noise measure. When A is the Schwartz space, the corresponding random element is a random distribution.

Strongly nuclear spaces

A strongly nuclear space is a locally convex topological vector space such that for any seminorm p we can find a larger seminorm q so that the natural map from Vq to Vp is a strongly nuclear.

See also

References

- Grothendieck, Alexandre (1955). "Produits tensoriels topologiques et espaces nucléaires". Mem. Am. Math. Soc. 16.

- Gel'fand, I. M.; Vilenkin, N. Ya. (1964). "Generalized Functions – vol. 4: Applications of harmonic analysis". OCLC 310816279.

- Takeyuki Hida and Si Si, Lectures on white noise functionals, World Scientific Publishing, 2008. ISBN 978-981-256-052-0

- T. R. Johansen, The Bochner-Minlos Theorem for nuclear spaces and an abstract white noise space, 2003.

- G.L. Litvinov (2001), "Nuclear space", in Hazewinkel, Michiel, Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Springer, ISBN 978-1-55608-010-4

- Pietsch, Albrecht (1972) [1965]. Nuclear locally convex spaces. Ergebnisse der Mathematik und ihrer Grenzgebiete 66. Berlin, New York: Springer-Verlag. ISBN 978-0-387-05644-9. MR 0350360

- Robertson, A.P.; W.J. Robertson (1964). Topological vector spaces. Cambridge Tracts in Mathematics 53. Cambridge University Press. p. 141.

- Schaefer, Helmuth H.; Wolff, M.P. (1999). Topological Vector Spaces. GTM 3. New York: Springer-Verlag. ISBN 9780387987262.

- Schaefer, Helmuth H. (1971). Topological vector spaces. GTM 3. New York: Springer-Verlag. p. 100. ISBN 0-387-98726-6.

- ↑ Schaefer p. 110

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||