Northern red snapper

| Northern red snapper | |

|---|---|

| |

| Conservation status | |

| Not evaluated (IUCN 3.1) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Actinopterygii |

| Order: | Perciformes |

| Family: | Lutjanidae |

| Genus: | Lutjanus |

| Species: | L. campechanus |

| Binomial name | |

| Lutjanus campechanus (Poey, 1860) | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

The northern red snapper, Lutjanus campechanus, is a species of snapper native to the western Atlantic Ocean including the Gulf of Mexico, where it inhabits environments associated with reefs. This species is commercially important and is also sought-after as a game fish.[1]

Characteristics

The northern red snapper's body is very similar in shape to other snappers, such as the mangrove snapper, mutton snapper, lane snapper, and dog snapper. All feature a sloped profile, medium-to-large scales, a spiny dorsal fin, and a laterally compressed body. Northern red snapper have short, sharp, needle-like teeth, but they lack the prominent upper canine teeth found on the mutton, dog, and mangrove snappers. This snapper reaches maturity at a length of about 39 cm (15 in). The common adult length is 60 cm (24 in), but may reach 100 cm (39 in). The maximum published weight is 38.5 kg (85 lb),[2] and the oldest reported age is 100+ years.[1] Coloration of the northern red snapper is light red, with more intense pigment on the back. It has 10 dorsal spines, 14 soft dorsal rays, three anal spines and eight to 9 anal soft rays. Juvenile fish (shorter than 30–35 cm) can also have a dark spot on their sides, below the anterior soft dorsal rays, which fades with age.[1]

Distribution

The northern red snapper is found in the Gulf of Mexico and the southeastern Atlantic coast of the United States and much less commonly northward as far as Massachusetts. In Latin American Spanish, it is known as huachinango or pargo.

This species commonly inhabits waters from 30–200 ft (9.1–61.0 m), but can be caught as deep as 300 ft (91 m) on occasion. They stay relatively close to the bottom, and inhabit rocky bottoms, ledges, ridges, and artificial reefs, including offshore oil rigs and shipwrecks. Like most other snappers, northern red snapper are gregarious and form large schools around wrecks and reefs. These schools are usually made up of fish of very similar size.

The preferred habitat of this species changes as it grows and matures due to increased need for cover and changing food habits.[3][4] Newly hatched red snapper spread out over large areas of open benthic habitat, then move to low-relief habitats, such as oyster beds. As they near one year of age, they move to intermediate-relief habitats as the previous year’s fish move on to high-relief reefs with room for more individuals. Around artificial reefs such as oil platforms, smaller fish spend time in the upper part of the water column while more mature (and larger) adults live in deeper areas. These larger fish do not allow smaller individuals to share this territory. The largest red snapper spread out over open habitats, as well as reefs.

Reproduction and growth

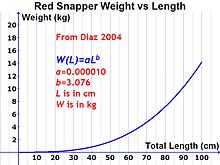

Diaz[5] reported weight vs. length data for L. campechanus for the National Marine Fisheries Service (US). As northern red snapper grow longer, they increase in weight, but the relationship between length and weight is not linear. The relationship between total length (L, in inches) and total weight (W, in pounds) for nearly all species of fish can be expressed by an equation of the form:

Invariably, b is close to 3.0 for all species, and c is a constant that varies among species.[6] Diaz reported that for red snapper, c=0.000010 and b=3.076. These values are for inputs of length in cm and result in weight in kg.

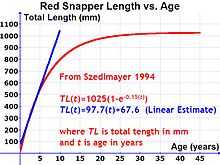

Szedlmayer et al. reported length vs. age data for L. campechanus in a primarily artificial reef environment off the coast of Alabama, USA: TL(age) = 1,025 (1 - e^( -0.15 age)), N=409, R = 0.96. For the first five years, growth can be estimated as being approximately linear: TL(age) = 97.7 age + 67.6, N = 397, R = 0.87 (for each equation, age is in years and total length is in mm).[7]

Northern red snappers move to different types of habitats during their growth process.[3] When they are newly spawned, red snapper settle over large areas of open benthic habitat(s). Below age 1, the red snapper move to low-relief habitats for food and cover. If available, oyster shell beds are preferred.[8] The second stage is when these fish outgrow low-relief habitats and move to intermediate-relief habitats as age 1 snapper leave to move on to another growth stage. Next, at about age 2, snapper seek high-relief reefs having low densities of larger snapper. Next, at platforms, smaller snapper occupy the upper water column. Then, the larger, older snapper occupy the deeper areas of the platforms and large benthic reefs and they prevent smaller snapper and other fish from using these habitats. In spite of local habitat preferences, Szedlmayer reported[7] that of 146 L. campechanus tagged, released and recaptured within about a year, 57% were still approximately at their respective release site, and 76% were recaptured within 2 km of their release site. The greatest movement by a single fish was 32 km.

A northern red snapper attains sexual maturity at two to five years old, and an adult snapper can live for more than 50 years. Research from 1999-2001 suggested the populations of red snapper off the coast of Texas reach maturity faster and at a smaller size than populations off of the Louisiana and Alabama coasts.[9]

Commercial and recreational use

Northern red snapper are a prized food fish, caught commercially, as well as recreationally. Red snapper is the most commonly caught snapper in the continental USA (almost 50% of the total catch), with similar species being more common elsewhere. They eat almost anything, but prefer small fish and crustaceans. They can be caught on both live and cut bait, and also take artificial lures, but with less vigor. They are commonly caught up to 10 lb (4.5 kg) and 20 in (510 mm) in length, but fish over 40 lb (18 kg) have been taken.

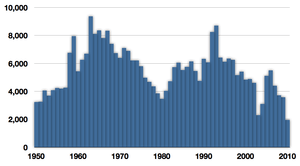

Recreational fishing for northern red snapper has been popular for a long time, restricted mostly by fishing limits intended to ensure a sustainable population. The first minimum size limit was introduced in 1984, after a 1981 report described quickly declining harvests (both commercial and recreational)[11] From 1985 to 1990, the annual recreational catch of red snapper was about 1.5 million. From 1991 to 2005, the catch was substantially higher, varying from year to year from 2.5 to 4.0 million.[12]

When northern red snapper bite on a line, they tend to be nibblers and pickers, and a soft touch is needed when trying to catch them.[13] Because the older red snapper like structure, anglers use bottom fishing over reefs, wrecks, and oil rigs, and use line and supplies in the 50-lb class. Since the anglers have to both choose the right bait and present it correctly, they tend to use multiple hooked baits. Favorite baits include squid, whole medium-sized fish, and small strips of fish such as amberjack. Although many northern red snapper are caught on the bottom, in some situations the larger fish are caught on heavy jigs (artificial lures), often tipped with a strip of bait or by freelining baits at the proper upper level.[14]

Interest in recreational fishing for northern red snapper, and in the Gulf of Mexico in general, has increased dramatically. From 1995-2003, the number of Louisiana fishing charter guide license holders increased eight-fold.[11]

Since 1990, the total catch limit for northern red snapper has been divided into 49% for recreational fishermen and 51% for commercial. Commercially, they are caught on multiple-hook gear with electric reels. Fishing for red snapper has been a major industry in the Gulf of Mexico, but permit restrictions and changes in the quota system for commercial snapper fishermen in the Gulf have made the fish less commercially available.[15] Researchers estimate the bycatch of young red snapper, especially by shrimp trawlers, is a significant concern.

Genetic studies have shown many fish sold as red snapper in the USA are not actually L. campechanus, but other species in the family.[16][17] Substitution of other species for red snapper is more common in large chain restaurants which serve a common menu nationwide. In these cases, suppliers provide a less costly substitute (usually imported) for red snapper. In countries such as India, where the actual red snapper is not available in its oceans, John snapper, Russell snapper, or a tomato red snapper are sold as "red snapper".[16][17]

-

-

Fisherman with a northern red snapper catch

-

Red snapper meal

Stocking in artificial reefs

Juvenile northern red snappers have been released on artificial reef habitats off the coast of Sarasota, Florida, to conduct investigations into the use of hatchery-reared juveniles to supplement native populations in the Gulf of Mexico.[18] Artificial reefs off the coast of Alabama have proven to be a favorite habitat of red snapper two years old and older. Gallaway et al.(2009) analyzed several studies and concluded, in 1992, 70 - 80% of the age two red snapper in that area were living around offshore oil platforms.[19]

Other species mistaken for red snapper

- Sebastes, rockfish, are called red snapper or Pacific red snapper.

- Several species of bigeye (Priacanthidae)

- Lane snapper

- Blackfin snapper

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2013). "Lutjanus campechanus" in FishBase. December 2013 version.

- ↑

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Gallaway, BJ, Szedlmayer, ST, Gazey, WJ. A life history review for red snapper in the Gulf of Mexico with an evaluation of the importance of offshore petroleum platforms and other artificial reefs. Reviews in Fisheries Science 17(1):48-67, 2009.

- ↑ Szedlmayer, ST. An evaluation of the benefits of artificial habitats for red snapper, Lutjanus campechanus, in northeast Gulf of Mexico. Proceedings of the Gulf and Caribbean Fisheries Institute, 2007

- ↑ Diaz, GA. Allometric relationships of Gulf of Mexico red snapper. National Marine Fisheries Service publication SEDAR7-AW-02, August, 2004

- ↑ R. O. Anderson and R. M. Neumann, Length, Weight, and Associated Structural Indices, in Fisheries Techniques, second edition, B.E. Murphy and D.W. Willis, eds., American Fisheries Society, 1996.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Szedlmayer, S.T. and R.L. Shipp. 1994. Movement and growth of red snapper, Lutjanus campechanus, from an artificial reef area in the northeast Gulf of Mexico. Bulletin of Marine Science 55:887-895.

- ↑ Szedlmayer ST and Howe JC. Substrate preference in age-0 red snapper, Lutjanus campechanus. Environmental Biology of Fishes 50:203-207, 1997

- ↑ Fischer 2004

- ↑ Based on data sourced from the FishStat database

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 LSU Fisheries Page on Red Snapper management accessed 5 July 2011.

- ↑ Scott GP. Estimates of historical red snapper recreational catch levels using US Census Data and Recreational Survey Information. National Marine Fisheries Service, August 2004, SEDAR7-AW16

- ↑ Red Snapper information on TakeMeFishing.org

- ↑ Schultz K. Essentials of Fishing: The only guide you need to catch freshwater and saltwater fish. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 2010, p. 90

- ↑ Hoyt Childers. "IFQ's first year raises ex-vessel prices, but quota cut leaves room for imports". National Fisherman. Retrieved July 31, 2008.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 E. Weise (July 14, 2004). "Bait and switch: study finds red snapper mislabeled". USA Today. Retrieved June 18, 2008.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 J. R. Fuller (May 10, 2007). "Fish fraud: The menus said snapper, but it wasn't!". Chicago Sun Times. Retrieved June 18, 2008.

- ↑ Brett Ramey Blackburn, Nathan Brennan & Ken Leber (2003). S. F. Norton, ed. "Diving for Science...2003". Proceedings of the American Academy of Underwater Sciences (22nd annual Scientific Diving Symposium): 19.

|chapter=ignored (help) - ↑ Gallaway, B.J. Szedlmayer, S.T. Gazey W.J. Reviews in Fisheries Science 17(1):48-67, 2009

References

- Red snapper NOAA FishWatch. Retrieved 13 November 2012.

External links

- Video: Red Snapper hunting (Red Sea, Egypt)

- Management of red snapper in the Gulf of Mexico Oversight Hearing before the Committee on Natural Resources, U.S. House of Representatives, 27 June 2013.