Nork, Surrey

| Nork | |

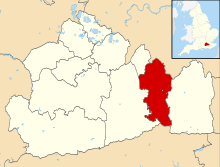

Nork ward in 2011, outlined in black[1] |

|

Nork |

|

| Area | 3.63 km2 (1.40 sq mi) |

|---|---|

| Population | 7,559 [2] |

| – density | 2,082/km2 (5,390/sq mi) |

| OS grid reference | TQ241598 |

| District | Reigate and Banstead |

| Shire county | Surrey |

| Region | South East |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | Banstead |

| Postcode district | SM7 |

| Dialling code | 01737 |

| Police | Surrey |

| Fire | Surrey |

| Ambulance | South East Coast |

| EU Parliament | South East England |

| UK Parliament | Epsom & Ewell |

Coordinates: 51°19′23″N 0°13′12″W / 51.323°N 0.220°W

Nork is a residential area of the borough of Reigate and Banstead in Surrey and borders Greater London, England. Nork is separated from its post town Banstead only by the A217 dual carriageway, and the built-up area is also contiguous with similar parts of Tattenham Corner and Burgh Heath. A thin belt of more open land separates it from the communities to the north: Epsom, Ewell, Cheam and Belmont. There is a parade of shops at the north-eastern end of Nork Way, the street which runs centrally through the residential area. Nork lies on chalk near the top of the gentle north-facing slope of the North Downs, 175 m above sea level at its highest point.

History

It has been suggested that the word "Nork", as well as "Nore" and "Nower", might derive from the Latin "noverca", which literally means a stepmother, but which was applied to a feature which dominates, and thus weakens, a fortified camp.[3] Others consider it more likely to be derived from the Old English word "nook", meaning secluded, tranquil and a corner.[4] A third proposed derivation is from "northern oak".[5]

Nork did not exist until the 18th or 19th century, when it could be considered an agricultural hamlet of Banstead village. The name of the area comes from Nork House, built there in the reign of Charles II. Originally Nork covered only the fields and buildings in the grounds of Nork Park (surrounding Nork House) in the southern part of the current council ward of Nork. Accordingly the railway station lying in the northern part of Nork ward had been named Banstead railway station when it opened in 1865, as it remains today. Housing development became rapid after 1923, and in 1925 the Nork Residents' Association was formed, publishing a bulletin the Nork Quarterly.[6][7] Nork began to be used as an official place name outside of the park itself from 1965 when Banstead was divided into two wards named "Banstead Village" and "Nork", equal in population and number of councillors.

Christopher Buckle (1684–1759) built Nork House, and his son, Admiral Matthew Buckle, died there.[8] His family were until the 19th century also owners of Burgh Manor at nearby Burgh Heath. Dr Burton, author of Iter Surriense, stayed at Nork House in 1752, and described at length the ingenious waterworks by which water was raised from a very deep well and distributed over the slopes of a dry down.[9]

In the 19th century, the Buckle family sold their estates to the Perceval/Arden family, who in turn sold them to the Colman family, of mustard fame.[6] In 1923, the Nork estate was sold to a development company and Nork House itself was demolished in 1939.[10] But in 1912 the Colman family had rebuilt another mansion on the other side of the Reigate Road called Great Burgh. This neo-Georgian house is now a Grade II listed building.[11] It was used as a research establishment by the Distillers Company, then by British Petroleum and Beecham Pharmaceuticals, and later as offices and accommodation by Toyota.[12]

In 1880 a large "cottage home" for children opened along the northern edge of Nork, between Fir Tree Road and the railway line. It was originally called The Kensington and Chelsea District School and later Beecholme. At its peak, over 400 children were accommodated. It closed in 1974 and the area rebuilt with modern housing.[13]

During World War II, Nork received only occasional damage from bombs and crashed aircraft. Some fortifications were built in preparation for an invasion, and later Canadian soldiers were stationed in Nork Park, occupying some of the buildings remaining from the estate.[14][15]

In a front garden along the The Drive lies Tumble Beacon, a scheduled ancient monument. Originally it was a prehistoric bowl barrow, a funeral monument situated, as is typical, on one of the highest prominences in the region. At latest in Tudor times, it was built up to serve as a beacon where a fire would be lit to warn of the approach of hostile forces. In World War II an air raid shelter was dug inside.[16][17]

A group of Saxon burial mounds, or hlaews, lies in the north part of Nork ward on the part of Banstead Downs west of the main A217 road. When one was excavated in 1972, archaeologists found 7th century artefacts (including a spear and knife) and skeletons. Some of the latter appeared to be from a later gallows that gave rise to the local place name Gally Hills.[18][19]

Amenities

The buildings in the area are predominantly detached or semi-detached houses[2] in an inter-war style, many with unusually large gardens (planning authorities often limited density to 6 houses per acre). There is much inconsistency in style in the original developments because different builders had purchased single plots.[6] Recently, in-fill development has converted some of the large rear gardens into small housing schemes; there is opposition to this from some local residents and their elected representatives.[21]

The shopping parade at the end of Nork Way consists of small convenience stores and local services such as hair salons, dentists, and restaurants.

In the west part of Nork is another small shopping area, known as The Driftbridge, named after the former Drift Bridge Hotel and adjacent garage at the crossroads of Fir Tree Road and the Reigate Road (A240). The hotel later became a Toby Inn[22] and in 2007 was converted into apartments.

The Anglican church of St Paul in Warren Road was opened in 1930 specifically to serve the new housing estates in Nork.[4] The main Roman Catholic and Methodist churches for Banstead are also situated in the Nork ward: for more details see the list of places of worship in Reigate and Banstead.

Transport

Banstead railway station lies near the shops at the north end of Nork Way. It is on the single-track Epsom Downs branch line between Epsom Downs station (also officially in the Nork ward) and the main-line junction at Sutton, from where trains continue to London. The line was opened in 1865 primarily to serve Epsom Downs Racecourse. At that time the end station at Epsom Downs had 9 platforms, but in 1989 the station was resited and rebuilt with just one platform.[23]

At the end of the parade of shops on Nork Way is a bus stop. The 166 bus service operates to Epsom and Croydon, through Banstead.[24] The 318 bus service runs between Banstead and Epsom.[25]

Nork Park

Nork Park lies to the south of the main residential area, bordering Tattenham Corner and Burgh Heath. It derives from the grounds around the demolished Nork House and was bought by the local council in 1947 from the landowner David Field.[10] The Park is partly chalk grassland of value for its flora, and there are also hedgerows, avenues and areas of woodland, including a small arboretum. It is much used for dog walking. There are extensive areas of playing fields, tennis and basketball courts, an exercise trail, two children's playgrounds, and a community centre. Several car parks provide access and adjacent parking is also possible along Nork Way. The local community organises a popular open-air music festival called "Music in the Park" that runs one afternoon in summer; 2014 marked the 18th such event.[26]

Schools

Warren Mead Infant School and Warren Mead Junior School are in Nork.[27] The Beacon School is located next to Nork Park, and was formerly known as Nork Park School. Residents are also likely to send their children to Sutton, Cheam, Croydon or Epsom for education.

Notable residents

- Admiral Matthew Buckle (1718-1784)[8]

- George James Perceval, 6th Earl of Egmont (1794 - 1874), admiral, Member of Parliament[28][29]

- Frederick Edward Colman, managing director of Colman's mustard manufacturers, bought Nork House in 1890 and lived there until his death in 1900; his family remained until 1923. The remains of the house are visible in Nork Park.

- The comedian David Walliams grew up in Nork and was a lifeguard at Banstead Sports Centre.

References

- ↑ Nomis. "2011 Ward Labour Market Profile E36005746 : Nork". Office for National Statistics. Retrieved March 5, 2015.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 "UK census data: Nork". UKCensusdata.com. Retrieved March 5, 2015.

- ↑ Urban, S. [pseudonym of E. Cave] (1843). "The novercae of Roman camps". Gentleman's Magazine, and Historical Chronicle 55: 140–141.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Anonymous. "A brief history of St Paul's church, Nork". Church of England. Retrieved March 5, 2015.

- ↑ Anonymous. "Roads". Banstead History Research Group. Retrieved March 19, 2015.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Banstead History Research Group (2005). The history of Banstead Vol. II: how a village grew and changed. Banstead History Research Group. ISBN 0951274198.

- ↑ Anonymous. "The Residents' Association: how it all began". Nork Residents' Association. Retrieved March 4, 2015.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Sweetman, J. "Matthew Buckle - Banstead's Naval hero". Banstead History Research Group. Retrieved 22 February 2015.

- ↑ H.E. Malden (editor) (1911). "Parishes: Banstead". A History of the County of Surrey: Volume 3. Institute of Historical Research. Retrieved 28 September 2013.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Old Surrey Downs Project. "Town and Down Circular Walk". Reigate and Banstead Borough Council. Retrieved March 5, 2015.

- ↑ Anonymous. "Great Burgh (including attached wall, railings, piers, terrace and steps)". English Heritage. Retrieved March 5, 2015.

- ↑ Savills Marketing. "Great Burgh, Epsom". Savills. Retrieved March 5, 2015.

- ↑ Maciejewski, R. (2010). Beecholme: a children's village. Banstead History Research Group. ISBN 978-0-9550768-4-8.

- ↑ Robinson, Geoffrey. "Me and the war in Banstead (part one)". BBC, Banstead History Centre. Retrieved March 19, 2015.

- ↑ Robinson, Geoffrey. "Me and the war in Banstead (part two)". BBC, Banstead History Centre. Retrieved March 19, 2015.

- ↑ English Heritage. "Bowl barrow and later beacon at Tumble Beacon". English Heritage. Retrieved March 5, 2015.

- ↑ Renn, Derek (April 29, 2004). Leatherhead Advertiser http://www.leatherheadlocalhistory.org.uk/2004.htm. Retrieved March 5, 2015. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ English Heritage. "Two Saxon burial mounds on Gally Hills, west of Brighton Road". Retrieved March 5, 2015.

- ↑ Reynolds, A. (2009). Anglo-Saxon Deviant Burial Customs. Oxford University Press. pp. 137–138. ISBN 9780191567650.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Lambert, H.C.M. (1912). History of Banstead. London: Oxford University Press.

- ↑ Anonymous (June 27, 2013). "Shock at proposal for "intensification" of homes in Nork and Tattenhams". Surrey Mirror. Retrieved March 13, 2015.

- ↑ East & Mid Surrey branch of Campaign for Real Ale. "Driftbridge". East Surrey pub guide. Retrieved March 5, 2015.

- ↑ Wymann, A. "The Epsom Downs Branch Website". Retrieved March 18, 2015.

- ↑ "166". Transport for London. Retrieved March 5, 2015.

- ↑ Anonymous. "Dorking, Leatherhead, Epsom and Banstead bus timetables". Surrey County Council. Retrieved March 19, 2015.

- ↑ Madden, C. (July 25, 2014). "Photos: Nork is alive with the sound of music". Surrey Mirror.

- ↑ "Schools by location". Surrey County Council. Retrieved March 5, 2015.

- ↑ Bouchard, Brian. "George James Perceval (1794 - 1874)". Epsom & Ewell History Explorer. Retrieved March 5, 2015.

- ↑ Smith, P. (Ed.) (2011). The Banstead boy at Trafalgar: George Perceval's letters to his parents Lord and Lady Arden 1805 to 1815. Banstead History Research Group. p. 55. ISBN 978-0-9566313-1-2.

External links

- Surrey County Council

- Schools in Banstead

- Zoomable boundary map and official labour market statistics

- Early pictures of Nork, particularly valuable for those of Nork House

- Francis Frith: photos, old OS map and anecdotes of Nork

- Francis Frith: photos and old OS map of Drift Bridge

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||