Noisy-storage model

The noisy-storage model[1] refers to a cryptographic model employed in quantum cryptography. It assumes that the quantum memory device of an attacker (adversary) trying to break the protocol is imperfect (noisy). The main goal of this model is to enable the secure implementation of two-party cryptographic primitives, such as bit commitment, oblivious transfer and secure identification.

Motivation

Quantum communication has proven to be extremely useful when it comes to distributing encryption keys. It allows two distant parties Alice and Bob to expand a small initial secret key into an arbitrarily long secret key by sending qubits (quantum bits) to each other. Most importantly, it can be shown that any eavesdropper trying to listen into their communication cannot intercept any information about the long key. This is known as quantum key distribution (QKD).

Yet, it has been shown that even quantum communication does not allow the secure implementation of many other two-party cryptographic tasks.[2][3][4][5] These all form instances of secure function evaluation. An example is oblivious transfer. What sets these tasks apart from key distribution is that they aim to solve problems between two parties, Alice and Bob, who do not trust each other. That is, there is no outside party like an eavesdropper, only Alice and Bob. Intuitively, it is this lack of trust that makes the problem hard. Unlike in quantum key distribution, Alice and Bob cannot collaborate to try and detect any eavesdropping activity. Instead, each party has to fend for himself.

Since tasks like secure identification are of practical interest, one is willing to make assumptions on how powerful the adversary can be. Security then holds as long as these assumptions are satisfied. In classical cryptography, i.e., without the use of quantum tools, most of these are computational assumptions. Such assumptions consists of two parts. First, one assumes that a particular problem is difficult to solve. For example, one might assume that it is hard to factor a large integer into its prime factors (e.g. 15=5x3). Second, one assumes that the adversary has a limited amount of computing power, namely less than what is (thought to be) required to solve the chosen problem.

Bounded storage

In information theoretic cryptography physical assumptions appear, which do not rely on any hardness assumptions, but merely assume a limit on some other resource. In classical cryptography, the bounded-storage model introduced by Ueli Maurer assumes that the adversary can only store a certain number of classical bits.[6][7] Protocols are known that do (in principle) allow the secure implementation of any cryptographic task as long as the adversary's storage is small. Very intuitively, security becomes possible under this assumption since the adversary has to make a choice which information to keep. That is, the protocol effectively overflows his memory device leading to an inevitable lack on information for the adversary. It was later discovered that any classical protocol which requires the honest parties to store  bits in order to execute it successfully can be broken by an adversary that can store more than about

bits in order to execute it successfully can be broken by an adversary that can store more than about  bits.[8] That is, the gap between what is required to execute the protocol, and what is required to break the security is relatively small.

bits.[8] That is, the gap between what is required to execute the protocol, and what is required to break the security is relatively small.

Bounded quantum storage

This gap changes dramatically when using quantum communication[9] . That is, Alice and Bob can send qubits to each other as part of the protocol. Likewise, one now assumes that the adversary's quantum storage is limited to a certain number of qubits. There is no restriction on how many classical bits the adversary can store. This is known as the bounded-quantum-storage model.[9][10] It was shown that there exist quantum protocols in which the honest parties need no quantum storage at all to execute them, but are nevertheless secure as long as Alice transmits more than twice the number of qubits than the adversary can store.

Noisy storage

More generally, security is possible as long as the amount of information that the adversary can store in his memory device is limited. This intuition is captured by the noisy-storage model,[1] which includes the bounded-quantum-storage model as a special case.[11] Such a limitation can, for example, come about if the memory device is extremely large, but very imperfect. In information theory such an imperfect memory device is also called a noisy channel. The motivation for this more general model is threefold. First, it allows one to make statements about much more general memory devices that the adversary may have available. Second, security statements could be made when the signals transmitted, or the storage device itself, uses continuous variables whose dimension is infinite and thus cannot be captured by a bounded storage assumption without additional constraints. Third, even if the dimension of the signals itself is small, the noisy-storage analysis allows security beyond the regime where bounded-storage itself can make any security statement. For example, if the storage channel is entanglement breaking, security is possible even if the storage device is arbitrarily large (i.e., not bounded in any way).

Assumption

The assumption of the noisy-storage model is that during waiting times  introduced into the protocol, the adversary can only store quantum information in his noisy memory device.[11] Such a device is simply a quantum channel

introduced into the protocol, the adversary can only store quantum information in his noisy memory device.[11] Such a device is simply a quantum channel  that takes input states

that takes input states  to some noisy output states

to some noisy output states  . Otherwise, the adversary is all powerful. For example, he can store an unlimited amount of classical information and perform any computation instantaneously.

. Otherwise, the adversary is all powerful. For example, he can store an unlimited amount of classical information and perform any computation instantaneously.

the storage device has to be used.

the storage device has to be used.The latter assumption also implies that he can perform any form of error correcting encoding before and after using the noisy memory device, even if it is computationally very difficult to do (i.e., it requires a long time). In this context, this is generally referred to as an encoding attack  and a decoding attack

and a decoding attack  . Since the adversary's classical memory can be arbitrarily large, the encoding

. Since the adversary's classical memory can be arbitrarily large, the encoding  may not only generate some quantum state as input to the storage device

may not only generate some quantum state as input to the storage device  but also output classical information. The adversary's decoding attack

but also output classical information. The adversary's decoding attack  can make use of this extra classical information, as well as any additional information that the adversary may gain after the waiting time has passed.

can make use of this extra classical information, as well as any additional information that the adversary may gain after the waiting time has passed.

In practise, one often considers storage devices that consist of  memory cells, each of which is subject to noise. In information-theoretic terms, this means that the device has the form

memory cells, each of which is subject to noise. In information-theoretic terms, this means that the device has the form  , where

, where  is a noisy quantum channel acting on a memory cell of dimension

is a noisy quantum channel acting on a memory cell of dimension  .

.

Examples

- The storage device consists of

qubits, each of which is subject to depolarizing noise. That is,

qubits, each of which is subject to depolarizing noise. That is,  , where

, where  is the 2-dimensional depolarizing channel.

is the 2-dimensional depolarizing channel.

- The storage device consists of

qubits, which are noise-free. This corresponds to the special case of bounded-quantum-storage. That is,

qubits, which are noise-free. This corresponds to the special case of bounded-quantum-storage. That is,  , where

, where  is the identity channel.

is the identity channel.

Protocols

Most protocols proceed in two steps. First, Alice and Bob exchange  qubits encoded in two or three mutually unbiased bases. These are the same encodings which are used in the BB84 or six-state protocols of quantum key distribution. Typically, this takes the form of Alice sending such qubits to Bob, and Bob measuring them immediately on arrival. This has the advantage that Alice and Bob need no quantum storage to execute the protocol. It is furthermore experimentally relatively easy to create such qubits, making it possible to implement such protocols using currently available technology.[12]

qubits encoded in two or three mutually unbiased bases. These are the same encodings which are used in the BB84 or six-state protocols of quantum key distribution. Typically, this takes the form of Alice sending such qubits to Bob, and Bob measuring them immediately on arrival. This has the advantage that Alice and Bob need no quantum storage to execute the protocol. It is furthermore experimentally relatively easy to create such qubits, making it possible to implement such protocols using currently available technology.[12]

The second step is to perform classical post-processing of the measurement data obtained in step one. Techniques used depend on the protocol in question and include privacy amplification, error-correcting codes, min-entropy sampling, and interactive hashing.

General

To demonstrate that all two-party cryptographic tasks can be implemented securely, a common approach is to show that a simple cryptographic primitive can be implemented that is known to be universal for secure function evaluation. That is, once one manages to build a protocol for such a cryptographic primitive all other tasks can be implemented by using this primitive as a basic building block. One such primitive is oblivious transfer. In turn, oblivious transfer can be constructed from an even simpler building block known as weak string erasure in combination with cryptographic techniques such as privacy amplification.

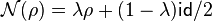

All protocols proposed to date allow one of the parties (Alice) to have even an unlimited amount of noise-free quantum memory. I.e., the noisy-storage assumption is applied to only one of the parties (Bob). For storage devices of the form  it is known that any two-party cryptographic task can be implemented securely by means of weak string erasure and oblivious transfer whenever any of the following conditions hold.

it is known that any two-party cryptographic task can be implemented securely by means of weak string erasure and oblivious transfer whenever any of the following conditions hold.

- For bounded-quantum-storage (i.e.,

), security can be achieved using a protocol in which Alice sends

), security can be achieved using a protocol in which Alice sends  BB84 encoded qubits.[11] That is, security can be achieved when Alice sends more than twice the number of qubits than Bob can store. One can also look at this from Bob's perspective and say that security can be achieved when Bob can store strictly less than half of the qubits that Alice sent, i.e.,

BB84 encoded qubits.[11] That is, security can be achieved when Alice sends more than twice the number of qubits than Bob can store. One can also look at this from Bob's perspective and say that security can be achieved when Bob can store strictly less than half of the qubits that Alice sent, i.e.,  .

.

- For bounded-quantum-storage using higher-dimensional memory cells (i.e., each cell is not a qubit, but a qudit), security can be achieved in a protocol in which Alice sends

higher-dimensional qudits encoded one of the possible mutually unbiased bases. In the limit of large dimensions, security can be achieved whenever

higher-dimensional qudits encoded one of the possible mutually unbiased bases. In the limit of large dimensions, security can be achieved whenever  . That is, security can always be achieved as long as Bob cannot store any constant fraction of the transmitted signals.[13] This is optimal for the protocols considered since for

. That is, security can always be achieved as long as Bob cannot store any constant fraction of the transmitted signals.[13] This is optimal for the protocols considered since for  a dishonest Bob can store all qudits sent by Alice. It is not known whether the same is possible using merely BB84 encoded qubits.

a dishonest Bob can store all qudits sent by Alice. It is not known whether the same is possible using merely BB84 encoded qubits.

- For noisy-storage and devices of the form

security can be achieved using a protocol in which Alice sends

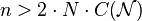

security can be achieved using a protocol in which Alice sends  BB84 encoded qubits if

BB84 encoded qubits if

-

,[11] where

,[11] where  is the classical capacity of the quantum channel

is the classical capacity of the quantum channel  , and

, and  obeys the so-called strong converse property,[14] or, if

obeys the so-called strong converse property,[14] or, if

-

-

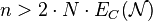

,[15] where

,[15] where  is the entanglement cost of the quantum channel

is the entanglement cost of the quantum channel  . This is generally much better than the condition on the classical capacity, however it is harder to evaluate

. This is generally much better than the condition on the classical capacity, however it is harder to evaluate  .

.

-

- For noisy-storage and devices of the form

security can be achieved using a protocol in which Alice sends

security can be achieved using a protocol in which Alice sends  qubits encoded in one of the three mutually unbiased bases per qubit, if

qubits encoded in one of the three mutually unbiased bases per qubit, if

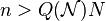

-

,[16] where

,[16] where  is the quantum capacity of

is the quantum capacity of  , and the strong converse parameter of

, and the strong converse parameter of  is not too small.

is not too small.

-

The three mutually unbiased bases are the same encodings as in the six-state protocol of quantum key distribution. The last condition does form the best known condition for most channels, yet the quantum capacity as well as the strong converse parameter are generally not easy to determine.

Specific tasks

Using such basic primitives as building blocks is not always the most efficient way to solve a cryptographic task. Specialized protocols targeted to solve specific problems are generally more efficient. Examples of known protocols are

- Oblivious transfer in the noisy-storage model,[11] and in the case of bounded-quantum-storage[9][10]

Noisy-storage and QKD

The assumption of bounded-quantum-storage has also been applied outside the realm of secure function evaluation. In particular, it has been shown that if the eavesdropper in quantum key distribution is memory bounded, higher bit error rates can be tolerated in an experimental implementation.[10]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Wehner, S.; C. Schaffner; B. Terhal (2008). "Cryptography from noisy-storage". Physical Review Letters 100 (22): 220502. arXiv:0711.2895. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.100.220502. PMID 18643410.

- ↑ Lo, H.; H. Chau (1997). "Is quantum bit commitment really possible?". Physical Review Letters 78 (17): 3410. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.78.3410.

- ↑ Lo, H (1997). "Insecurity of Quantum Secure Computations". Physical Review A 56 (2): 1154. doi:10.1103/PhysRevA.56.1154.

- ↑ Mayers, D. (1997). "Unconditionally Secure Quantum Bit Commitment is Impossible". Physical Review Letters 78 (17): 3414––3417. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.78.3414.

- ↑ D'Ariano, G.; D. Kretschmann and D. Schlingemann and R.F. Werner (2007). "Quantum Bit Commitment Revisited: the Possible and the Impossible". Physical Review A 76 (3): 032328. doi:10.1103/PhysRevA.76.032328.

- ↑ Maurer, U. (1992). "Conditionally-Perfect Secrecy and a Provably-Secure Randomized Cipher". Journal of Cryptology 5 (1): 53––66. doi:10.1007/bf00191321.

- ↑ Cachin, C.; U. Maurer (1997). "Unconditional Security Against Memory-Bounded Adversaries". Proceedings of CRYPTO 1997: 292–306.

- ↑ Dziembowski, S.; U. Maurer (2004). "On Generating the Initial Key in the Bounded-Storage Model". Proceedings of EUROCRYPT: 126–137.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 I., Damgaard; S. Fehr and L. Salvail and C. Schaffner (2005). "Cryptography in the Bounded-Quantum-Storage Model". Proceedings of 46th IEEE Symposium on Foundations of Computer Science: 449–458.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 Damgaard, I.; S. Fehr and R. Renner and L. Salvail and C. Schaffner (2007). "A Tight High-Order Entropic Quantum Uncertainty Relation With Applications". Proceedings of CRYPTO 2007: 360––378.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 11.5 Koenig, Robert; S. Wehner and J. Wullschleger (2009). "Unconditional security from noisy quantum storage".

- ↑ Wehner, S.; M. Curty and C. Schaffner and H. Lo (2010). "Implementation of two-party protocols in the noisy-storage model". Physical Review A 81 (5): 052336. doi:10.1103/PhysRevA.81.052336.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Mandayam, P.; S. Wehner (2011). "Achieving the physical limits of the bounded-storage model". Physical Review A 83 (2): 022329. doi:10.1103/PhysRevA.83.022329.

- ↑ Koenig, R.; S. Wehner (2009). "A Strong Converse for Classical Channel Coding Using Entangled Inputs". Physical Review Letters 103 (7): 070504. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.103.070504. PMID 19792627.

- ↑ Berta, M.; F. Brandao and M. Christandl and S. Wehner (2011). "Entanglement cost of quantum channels".

- ↑ Berta, M.; O. Fawzi; S. Wehner (2011). "Quantum to classical randomness extractors". arXiv:1111.2026.

- ↑ Damgaard, I.; S. Fehr and L. Salvail and C. Schaffner (2007). "Identification and QKD in the Bounded-Quantum-Storage Model". Proceedings of CRYPTO 2007: 342––359.

- ↑ Bouman, N.; S. Fehr, C. Gonzales-Guillen and C. Schaffner (2011). "An All-But-One Entropic Uncertainty Relations, and Application to Password-based Identification".