Noel Rockmore

| Noel Rockmore | |

|---|---|

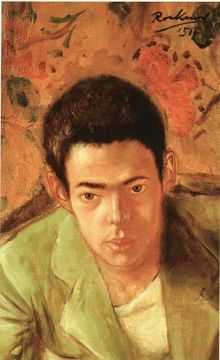

1951 self-portrait, age 21, NYC | |

| Born |

Noel Montgomery Davis December 15, 1928 New York City, New York, U.S. |

| Died |

February 19, 1995 (aged 66) Kenner, Louisiana, U.S. |

| Nationality | American |

| Education | Art Students League of New York |

| Known for | Painter |

| Movement | Realism |

| Awards | Hallgarten Prize, Tiffany Fellowship, Ford Foundation Award |

| Patron(s) | Joseph Hirshhorn, Vincent Price, George Wein, Jimmy Buffett |

Noel Rockmore (December 15, 1928 – February 19, 1995) was born Noel Montgomery Davis to his mother, Gladys Rockmore Davis, and his father, Floyd Davis, in New York City.[1] Rockmore was an American painter, draughtsman, and sculptor. He claims to have produced more than 15,000 works of art in his lifetime.[2] He is known for his portraits, his early rise to fame, his Preservation Hall portraits, and for changing his name at the height of the popularity he had developed in New York City.

Noel painted in a realistic and old masters style throughout his childhood and adolescence. He experimented with different artistic theories, techniques, and ideas in the New York art world of the 1950s.[1]

As the abstract expressionist movement gained momentum, Rockmore left New York and went to New Orleans, where he changed his name from Noel Davis to Noel Rockmore, adopting the surname of his mother. He spent the next 20 years commuting between New Orleans and New York City while various dealers tried unsuccessfully to manage him and his often, volatile career.

1928-47: Early life

Noel Davis grew up in New York City, the son of a painter, Gladys Rockmore Davis, considered the ten-year-wonder of United States Art.[3] His father, Floyd Davis was recognized in 1943 by Life Magazine as the No. 1 illustrator of that time.[4] Noel’s younger sister, Deborah Davis, was born in 1930.

Noel was fascinated by the violin and began lessons at the age of 5. He also learned piano and guitar. In 1935 both children contracted polio. and Noel turned to painting as an artistic outlet. By the age of 11 he had begun to produce serious artistic works.

Noel had difficulty accepting the discipline in traditional schools and at Juilliard, where he worked briefly trying to master the violin skills he had demonstrated as a child musical prodigy.[1]

In the early 1940s, while his parents covered World War II as art correspondents for Life magazine, Noel and his sister attended the progressive Putney School in Vermont. Noel was known as a talented, but difficult student. He was graduated in 1947. He also attended the Art Student League of New York with Julian Levi.[5]

1948-50: Career beginnings

In 1948, when Rockmore was 19, Joseph Hirshhorn became his first major patron. He was encouraged by Henry Francis Taylor, director at the Metropolitan Museum, as well as by Raphael Soyer, John Koch, and Yasuo Kuniyoshi. His first studio was in the Cooper Union Complex in New York City, where he painted the street people of the Bowery.

He painted animals from The Museum of Natural History. and in 1950 he acquired access to the backstage of the Ringling Brothers Circus. Coney Island, Fire Island, and Central Park. all of which provided stimulus and inspiration for his drawings and paintings. He did early works in the “Old Masters Style” that were favorably reviewed by Stewart Preston of the New York Times. Xavier Gonzalez, Jack Levine, and Fletcher Martin all encouraged Noel Davis to ignore the art fads of the time, including abstract expressionism, and persevere in his own unique direction.[1]

1951-58: Married life and career

On June 20, 1951, Noel Davis married Elizabeth Hunter in New York City.[6] On their honeymoon in Valles, Mexico, his car hit a cow and was demolished. The newlyweds were uninjured, although the bride was upset when Noel insisted upon sketching the dying animal. Upon the couple's return to New York. they settled into the typical life of a young married couple, living in the "Des Artistes" complex. From 1951 to 1957 there were three children born of the marriage.[7]

He began showing his works at the Harry Salpeter Gallery and received awards and recognitions that, according to Des Artiste fellow resident Stuart Davis put the Salpeter Gallery on the map. He did two Life Magazine commissions and was invited to join the National Academy of Design. He was in group exhibitions at the Metropolitan Museum, Whitney Museum, Museum of Modern Art, and The Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts. He won the Hallgarten Prize, the Tiffany Fellowship (twice: 1956 & 1963), and The Wallace Truman Prize.

In 1958, Joseph Hirshhorn purchased an additional eight Noel Davis paintings, bringing his total to 16 for the Hirshhorn Museum. He had a one-man show at the Salpeter Gallery in New York and the The Butler Institute of American Art in Ohio. Later that year he moved to Brooklyn Heights as his marriage dissolved as well as his relationship with Harry Salpeter. Upon leaving his wife and children, he moved to Coney Island, and then Xavier Gonzalez arranged for him to obtain a studio in the house of New Orleans painter Paul Ninas, where. according to Davis, he could "dwell in creative obscurity”.[8]

1959-60: Journey to New Orleans

While in New Orleans, Noel Davis decided to legally change his name to Noel Rockmore, adopting his mother’s maiden name. This caused consternation from his patrons, his dealer and most notably, his mother.[5] It was unheard of for a major recognized artist in so many museums to change his name at such a point in his career. He was banned from the Hirshhorn Museum when he was caught there changing his name from Davis to Rockmore on one of his works. He was also accused of defacing a major work at a museum in New York (possibly a Jackson Pollock).[8]

Once in New Orleans he observed that he need only to record what actually existed to convey the moods he wished to express in his art. He met E. Lorenz Borenstein, gallery owner, Pre-Columbian artifact dealer, Preservation Hall co-founder, and real-estate entrepreneur. He also met Bill Russell, composer, jazz historian, and New Orleans merchant and they began a lifelong friendship that would be punctuated by Rockmore's depiction of Bill in numerous paintings and watercolors throughout his life. While in New Orleans, Rockmore found a new list of patrons that truly admired his work including Shirley Marvin and the Faubles who would become his patrons for life.[7]

Rockmore spent 1959-1960 painting New Orleans, specifically the French Quarter and the black residents of the city as they were. Paul Ninas, Rockmore’s landlord writes a letter to Salpeter in New York reporting that Rockmore is cavorting with young female companions, wearing western boots and tight jeans, using Castor oil in his hair and drinking for days on end.[8]

1961-63: Return to New York

Rockmore returned to New York and his arrangement with Harry Salpeter was slowly dissolved. In 1961 he began to exhibit his work with Greer Gallery, which offered him greater exposure. While in New York, Rockmore, recently single, paints and pursues many relationships with young, well endowed beauties, which became a trademark of both his paintings and his public persona.[8]

1963-65: New Orleans - Preservation Hall years

Upon Rockmore’s return to New Orleans, Borenstein had found a young couple, Sandra and Allan Jaffe, who had turned Preservation Hall into a going concern featuring old jazz musicians.[9] Borenstein commissioned Rockmore to document all of these musicians as fast as he can. Rockmore responded with 300 oil portraits and over 500 small acrylics in less than two years.[7] The portraits included the following jazz musicians: Billie & DeDe Pierce, George Lewis, Odetta, Dizzy Gillespie, Jim Robinson, Cie Frazier, Louis Nelson, Punch Miller, Oscar Chicken Henry, Kid Thomas Valentine, Joe Robichaux, Narvin Kimball, Danny Barker, Alcide Pavageau, Kid Sheik Cola, Percy Humphrey, Willie Humphrey, and Emma Barrett (Sweet Emma the Bell Gal) to name a few.[10]

Rockmore worked with a framer, Bruce Brice, whom he mentored and encouraged on his career path, and who eventually became a respected American folk artist.[11] Rockmore, Borenstein and Bill Russell collaborate on a book, Preservation Hall Portraits, which featured Rockmore’s works and was published in 1968.[10] After 1965, much to Borenstein's disappointment, Rockmore chose to do new series including shipyards and construction sites In New Orleans. Borenstein had experienced much success with selling Rockmore’s jazz pieces and wished him to continue the winning formula.[12]

In 1965, another relationship was formed with Jon and Gypsy Lou Webb publishers of “The Outsider” featuring Charles Bukowski. Their company, Lou-Jon Press published Crucifix in a Death Hand" featuring Bukowski’s poetry and Rockmore’s art.[13]

In 1963, Rockmore created a series of works based on his travels in Mexico, and in 1965, he did the same concerning his travels to Morocco. In 1964, he won a Ford Foundation Award that resulted in a show at the Swopes Art Museum in Terre Haute, Indiana where he was artist-in-residence.[5]

1965-69: New York, New Orleans, and San Francisco

In 1965-66, Rockmore decided to do a series of family portraits of his aging parents, Floyd and Gladys Rockmore Davis. During this time, Rockmore was also involved in scandals with several underage women; one such scandal in 1966 landed Rockmore in court in NYC on charges of which he is eventually acquitted.[8] Another incident involved a 16-year-old New Orleans girl Rockmore nicknamed Saki and of whom he painted a full nude portrait that was discovered in Borenstein’s Gallery by the girl's father. Saki and Rockmore’s relationship would continue in secret for nearly a year before she decided to break it off.[12]

In late 1966, Rockmore’s father Floyd Davis died; shortly thereafter in early 1967, his mother Gladys Rockmore Davis died as well.[14] Rockmore retreated to San Francisco to be with his sister Deborah, painting San Francisco and Haight-Ashbury as well as Eldredge Cleaver, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, and Allen Ginsburg.[12]

In 1967, Luba and Victor Potamkin, a Cadillac dealer from New York, and Sergio Franchi, world famous tenor, decided that they would manage Rockmore. They arranged for his biggest show ever, set to take place in New York City in November 1967 at Greer Gallery. The big opening was completely shut down by an anti-war riot at the New York Hilton where Dean Rusk was to speak.

In early 1968, Potamkin and Franchi sent Rockmore to Israel to produce a series for his next big show. The works captured much of the tension and anguish in Israel at the time, and a show is held at the Crane Korchin Gallery in PA in May. Rockmore took up with a young girl, Robin Levine, whom he married, but he divorced her by the end of the year.

Rockmore also painted a portrait of the writer Henry Miller for a Lou-Jon press book which was rejected when the Borenstein negotiation with Lou-Jon goes bad. In early 1969 Rockmore parted ways with Potamkin and Franchi and returned to San Francisco to visit his sister and paint a new series.[12]

1969–73: Return to New Orleans and Jazzfest

At the end of 1969, Rockmore returned to New Orleans and reunited with Larry Borenstein, who got him a commission from George Wein to create posters for sale to commemorate the very first New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival (Jazz Fest). Rockmore was also included by Wein on the inaugural Jazz Fest committee and commissioned to do a watercolor series of the event.[15]

The first two New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festivals in 1970 and 1971 were held in Louis Armstrong Park, then known as Beauregard Square, in the area of the park known to be the historic Congo Square and the adjoining New Orleans Municipal Auditorium. Artist Noel Rockmore and Bruce Brice did posters for the first New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festivals in 1970.

At that time, Rockmore began a relationship with folk artist Sister Gertrude Morgan and painted and worked with her throughout 1970. He embraced and painted many famous characters from the French quarter, including Mike Stark and his Free Head Clinic, Ruthie the Duck Girl, the jazz musicians Bill Russell and Gypsy Lou, and his new girlfriend Riva Segall.[5]

In 1971, he was commissioned by Time Magazine to do a cover portrait of then Governor Jimmy Carter, which was rejected as “too realistic” for Time. He was also commissioned by Time to do a portrait of Arial Sharon. In 1971, Rockmore did a Civil War series and a Victorian Scrapbook series where he transported himself back in time in order to paint periods he had researched.

In 1972, Wein commissioned Rockmore to go to Paris and Venice with girlfriend Riva in order to create a series of works for Wein’s personal collection. Rockmore and Riva parted ways at the conclusion of the trip and after a brief stay in New York, Rockmore returned to New Orleans, where he took up with Mickey Cahn for a year. By then, Rockmore was working with Bryant Galleries in New Orleans, having permanently split with Borenstein.[12]

1974-77: Final return to New York City

In 1974, Rockmore moved back to New York and started a series of large murals throughout the city. McGlade’s bar and Café des Artistes became his hangout, as well as a display place for his art. In late 1974, the Lakeview Center for the Arts in Peoria, IL put on the retrospective “The World of Noel Rockmore” with a black and white brochure of major works Rockmore decided he could procure for the show.[1] In 1976 Rockmore had his last New York City show at the Forum Gallery. He took up with a young Andrea Lannin and reunited with two of his children, one of his daughters and his son. In 1977 Rockmore sold his West 67th apartment in New York and left the city for the last time.[12]

1977-87: Final return to New Orleans

In 1977, Rockmore returned to New Orleans with girlfriend Andrea Lannin, and two of his children, now young adults, came to stay with him as well. By the end of the year Lannin had moved on and Rockmore had re-engaged himself with Bryant Galleries. He began a series of prints, etchings, and posters, including the famous Muhammad Ali and Leon Spinks Fight Print of 1978 from the Superdome.

While in New Orleans, he also created his well-known Jonestown Triangle painting, which depicts Jim Jones and the Jonestown suicides. He was commissioned by George Wein to do an “Homage to the New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival”, and also began a five-year intimate relationship with Rita Posselt.

By 1981 he split with Bryant Galleries. He was now represented by the Sandra Zahn Oreck Gallery and had three very successful shows during the next three years that included his “Mardi Gras Backstage series” from the Blaine Kern warehouses. Sandra Zahn Oreck closed the gallery in 1983 and Rockmore chose to seek representation with Bryant Galleries once again.

Bryant Galleries sent Noel and Rita to document Haiti, where he captured the Haitian culture, particularly the Haitian Vodou aspect. By the end of 1983, Noel and Rita had separated. In 1984, Rockmore first came into the possession of a puppy that he named Remby, who would be with him until right before his death in 1995. He began work on fantastic vodou pieces, sculptures, and three-dimensional collages.

In late 1984 Rockmore took up with a local entrepreneur, William May, originally from LaGrange, GA who would attempt to manage Rockmore back to New York for a big show. William May sequestered Rockmore away in a house in Mill Valley, CA and supplied him with canvas, paint, materials, and money to live on. May was unable to procure the New York show and had to settle for the Chattahoochee Valley Art Association of LaGrange, GA.[12]

Rockmore, now 56, returned to New Orleans. There, he began a relationship with his final significant girlfriend, Mary May Impastato, an eighteen-year-old girl from the French Quarter. One of his painting from the Mill Valley series was purchased by Jimmy Buffett, who attributes his song “Bring Back the Magic”, reaching #24 on the charts, to Rockmore’s painting.[16] By late 1985 Noel was represented by the Posselt-Baker gallery of New Orleans.

In 1986-87, Rockmore was frustrated by his lack of recognition and funds. His drinking escalated and his relationship with Mary May started to deteriorate. Nevertheless, his work output continued with the creation of several new series including the Ceasarian series, French Quarter pastels, and a new Grid series inspired by football betting cards. He attended Alcoholics Anonymous and worked hard to reconcile his relationship with Mary May, but by the end of 1987 she had gone and Rockmore was once again alone and without a gallery.[12]

1988-95: The final chapter

In 1988, Rockmore was in despair, an agony reflected in the nature of his work. He signed a deal with Bryant Gallery in order to get a regular paycheck; while with Bryant, he was befriended by Dr. Hava, a psychiatrist and drinking buddy from Johnny White's, his favorite watering hole in the French Quarter. Dr. Hava put Rockmore on Zoloft in the hopes of allowing him to regain his focus and control his behavior. It seemed to work. Rockmore began to exercise, working out at the YMCA; his new-found motivation allowed him to move forward and produce an entirely new “Ancient Egyptian” series in 1990. In 1991, he had a well received Egyptian show at Bryant Galleries.

In 1991 his long time patron Shirley Marvin had the professional documentary “Rockmore” produced in New Orleans, featuring Rockmore and narrated by his daughter. In 1992 he began work on an “immigration series” featuring Ellis Island, but was hospitalized that summer with an intestinal disorder. While hospitalized, he underwent detoxification from alcohol; he was able to remain sober for a month and half after being released. He completed the “immigration series” and had his final exhibition at Bryant Galleries at the age of 64.

In 1993 he began a dramatic series of huge works and collages to detail his march towards death. By late 1994 he was quite ill. He created his “final” self-portrait. He refused to go to the hospital despite attempts by his friends to intervene. He chose instead to go to the home of his friend Dr. Hava, whom he depicted as Dr. Jack Kevorkian in one of his final works.

On Friday February 17, 1995, the day Rockmore was to lose his life, an open house was scheduled at Dr. Hava’s but did not occur. Rockmore was put in a cab and the cabbie was told by the doctor that Rockmore was a street person to be dropped off at St. Jude Medical Center in Kenner, LA. According to the admitting nurse, as recorded in a letter to Rockmore’s sister, as Rockmore was put on the gurney to be admitted to the hospital, he heard that he was thought to be a street person, and he raised himself up and said “I am not a street person, I am a great artist.” Noel Rockmore lost consciousness and died, two days later, on February 19, 1995 at the age of 66. His body was donated to medical science.[12]

Posthumous recognition

In 1998, a retrospective was held at the New Orleans Museum of Art, sponsored by Shirley Marvin, Preservation Hall, and NOMA. The show “Noel Rockmore: Fantasies and Realities” was presented by curator Gail Fiegenbaum and included a brochure and panel discussion with George Wein, Shirley Marvin and Rita Posselt.[5]

In November 2006, one year after Hurricane Katrina, Rich and Tee Marvin, Shirley’s son and daughter-in-law, discovered over fourteen hundred (1,400) Rockmore works in Shirley Marvin’s storage facility in New Orleans. They also found 35 years worth of correspondence, every Rockmore brochure and news article, as well as a documentary film all related to the life of Noel Rockmore.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Rockmore, Noel, The World of Noel Rockmore, Published by Greer Gallery, New York, 1967, ASIN B0007F9S4M

- ↑ Lutter, Neil, Rockmore’s diverse art defies definition, news article published by Clarion Ledger - Jackson, MS, 1/14/1990

- ↑ Watson, Ernest, Gladys Rockmore Davis - Her Adventure in Pastel, American Artist February 1942, Published by Watson-Guptill Publications, PA, 1942

- ↑ Paxton, Worthen, Gladys Rockmore Davis, Pg.44 Life Magazine April 19, 1943, Vol 14, NO. 16

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 Feigenbaum, Gail, Noel Rockmore - Fantasies and Realities, Published by the New Orleans Museum of Art, 1998, ISBN 978-0-89494-070-5

- ↑ New York Times Wedding Announcements, Elizabeth Hunter Married in Chapel, Published by New York Times, June 21, 1951

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Rockmore, Noel & Borenstien, Larry, Rockmore Biography, Manuscript written 3-15-1973, available on web at www.rockmore.org

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 Salpeter, Harry, “Harry Salpeter Diaries", Archives of American Art Microfilm, Reels 690-691, 1956-60

- ↑ Carter, William, Preservation Hall - Music from the Heart, Published by W.W. Norton Co., New York, 1991 ISBN 978-0-393-02915-4

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Rockmore, Noel & Borenstien, Larry, & Russell, Bill, Preservation Hall Portraits, Published by LSU Press, Baton Rouge, 1968 LCCN 68-28494

- ↑ Mitchell, Patricia, Bruce Brice: The Today Show via Jackson Square, The Community Standard magazine, French Quarter, New Orleans, Volume 1, No. 2, December 1974

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 12.5 12.6 12.7 12.8 Marvin, Shirley, Letters and Diaries: The Rockmore Collection, Unpublished, transcribed by The Noel Rockmore Project, 2010

- ↑ Bukowski, Charles, Crucifix in a Death Hand, Published by Lou Jon Press, New Orleans, 1965 ASIN B000K1SQ78

- ↑ The New York Times, obituaries

- ↑ Wein, George, Myself Among Others: A Life in Music, Published by Da Capo Press, Cambridge, MA, 2003 ISBN 978-0-306-81114-2

- ↑ Buffett, Jimmy & Jennings,Will, Bring Back the Magic, Hot Water Album, 1988 - “Inspired by a Noel Rockmore painting entitled "Ride of the Beachcombers". “I bought the painting and sat with it for a morning in New Orleans and let it and the town talk to me.”

External links

- Bohemian New Orleans: The Story of the Outsider and Loujon Press

- NY Times Obituary for Victor Potamkin

- Info on Ruthie The Duck Lady

- LaGrange Art Museum Online

|