Nodjmet

| Nodjmet | |

|---|---|

| Queen consort of Egypt | |

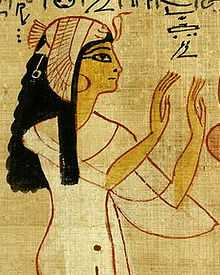

Nodjmet depicted as a queen, from her Book of the Dead papyrus. | |

| Spouse | possibly Piankh, then Herihor |

| Issue | Pinedjem I and others (see text) |

| Father | Ramesses XI? |

| Mother | Hrere |

| Died | c. 1064 BCE |

| Burial | Thebes, eventually in TT320 |

Nodjmet was an ancient Egyptian noble lady of the late 20th-early 21st dynasties of Egypt, mainly known for being the wife of High Priest of Amun at Thebes, Herihor.

Biography

| |||||

| Nodjmet in hieroglyphs |

|---|

Nodjmet may have been a daughter of the last ramesside pharaoh, Ramesses XI, and likely even Piankh's wife, if the latter really was Herihor's predecessor as supported by Karl Jansen-Winkeln.[1] Early in her life, she held titles such as Lady of the House and Chief of the Harem of Amun.[2]

According to the two Egyptologists Aidan Dodson and Dyan Hilton,[3] Nodjmet had several children with her first husband Piankh: Heqanefer, Heqamaat, Ankhefenmut, Faienmut (a female) and, the most famous of all, the future High Priest of Amun/Pharaoh Pinedjem I. Nodjmet became Piankh's most trusted confidant, and every time he had to fulfill his business in Nubia, the management of Thebes was left to her. When around 1070 BCE Piankh died, Herihor was proposed as his successor; Nodjmet, however, managed to keep her prerogatives marrying this man.[4] Later, Herihor claimed “kingship” – although only inside the borders of the Temple of Amun at Karnak – Nodjmet effectively became his “queen”: her name was inscribed inside a cartouche and later she bore titles such as Lady of the Two Lands and King's Mother.[2]

Nodjmet outlived even her second husband, and finally died in the first years of pharaoh Smendes (c. 1064 BCE).[5]

Nodjmet's mummy

Her mummy was discovered in the Deir el-Bahari cache (TT320). The body is that of an old woman. She had been embalmed with a new mummification technique which involved the use of fake eyes and the packing of the limbs. The heart was still in place inside her body.[6] With her mummy two Books of the Dead were found.[7] One of them, Papyrus BM 10490, now in the British museum, belonged to “the King’s Mother Nodjmet, the daughter of the King’s Mother Hrere”. Whereas the name of Nodjmet was written in a cartouche, the name of Hrere was not. Since mostly this Nodjmet is seen as the wife of the High Priest Herihor, Herere’s title is often interpreted as “King’s Mother-in-law”,[8] although her title “who bore the Strong Bull” suggests that she actually must have given birth to a king.[9]

One or two Nodjmets?

However, recently, the common opinion that there was only one Queen Nodjmet has been challenged and the old view that the mummy found in the Royal Cache was that of the mother of Herihor rather than his wife has been revived.[10][11] Although it is beyond dispute that Herihor had a queen called Nodjmet (this was already recognised by Champollion), as far back as 1878 Naville postulated that Herihor must have had a mother called Nodjmet. He did so on the basis of Papyrus BM 10541, the other Book of the Dead found with her mummy. As A. Thijs has recently pointed out, it is indeed remarkable that, although Herihor figures in P. BM 10541, Nodjmet nowhere in her two Books of the Dead is designated as “King’s Wife”. All the stress is on her position as “King’s Mother”. The ruling family from the transitional period from the 20th to the 21st dynasty is notorious for the repetitiveness of names, so Herihor having a homonymous wife and mother would in itself not be impossible. If the Nodjmet from the Royal Cache was indeed the mother of Herihor, it follows that Hrere must have been the grandmother of Herihor rather than his mother(-in-law). In this position Hrere could well have been the wife of the High Priest Amenhotep.[12]

It has been proposed to refer to the Nodjmet found in the Royal Cache as "Nodjmet A" (=the mother of Herihor) and to the wife of Herihor as "Nodjmet B". Nodjmet as wife of Herihor has been attested in the Temple of Khonsu where she is depicted at the head of a procession of children of Herihor, and on Stela Leiden V 65, where she is depicted with Herihor who is presented as High Priest without royal overtones.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Nodjmet. |

References

- ↑ Karl Jansen-Winkeln, “Das Ende des Neuen Reiches”, ZAS 119 (1992), pp. 22-37.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Kitchen, The Third Intermediate Period in Egypt (1100–650 BC), 1996, Aris & Phillips Limited, Warminster, 40-45.

- ↑ Aidan Dodson & Dyan Hilton, The Complete Royal Families of Ancient Egypt, Thames & Hudson, 2004, ISBN 0-500-05128-3, pp. 200-201.

- ↑ John Taylor, Nodjmet, Payankh and Herihor: The end of the New Kingdom reconsidered, in Christopher J. Eyre (ed), Proceedings of the Seventh International Congress of Egyptologists, Leuven 1998, pp. 1143-55.

- ↑ Kitchen, o.c., 81, n.397.

- ↑ Margaret R. Bunson, Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, revised edition, 2002, Facts on File, New York, pp. 279-80.

- ↑ Kitchen, o.c., 42-45

- ↑ Kitchen, o.c., 44

- ↑ Wente, JNES 26 (1967), 173-174

- ↑ Ad Thijs, Two Books for One Lady, The mother of Herihor rediscovered, GM 163 (1998), 101-110

- ↑ Ad Thijs, Nodjmet A, Daughter of Amenhotep, Wife of Piankh and Mother of Herihor, Zeitschrift für Ägyptische Sprache und Altertumskunde 140 (2013), 54-69.

- ↑ Thijs, Nodjmet A, Daughter of Amenhotep, Wife of Piankh and Mother of Herihor, ZÄS 140 (2013), 54-69.

Bibliography

- E. A. Wallis Budge, Facsimiles of the Papyri of Hunefer, Anhai, Kerasher and Netchemet, London 1899

- Kenneth Kitchen, The Third Intermediate Period in Egypt (1100–650 BC), 1996, Aris & Phillips Limited, Warminster, ISBN 0-85668-298-5.

- Ursula Rößler-Köhler, Piankh - Nedjemet - Anchefenmut - eine Kleinigkeit, GM 167 (1998), 7-8

- John Taylor, Nodjmet, Payankh and Herihor: The end of the New Kingdom reconsidered, in Christopher J. Eyre (ed), Proceedings of the Seventh International Congress of Egyptologists, Leuven 1998, 1143-1155

- Ad Thijs, Two Books for One Lady, The mother of Herihor rediscovered, GM 163 (1998), 101-110

- Ad Thijs, Nodjmet A, Daughter of Amenhotep, Wife of Piankh and Mother of Herihor, Zeitschrift für Ägyptische Sprache und Altertumskunde 140 (2013), 54-69.