Noblesse Oblige (book)

| |

| Editor | Nancy Mitford |

|---|---|

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Subject | Linguistic |

| Genre | Essays |

| Publisher | Hamish Hamilton |

Publication date | 1956 |

| Pages | 114 |

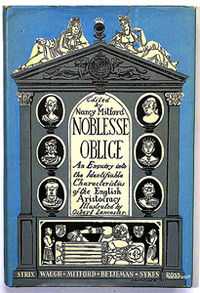

Noblesse Oblige: An Enquiry Into the Identifiable Characteristics of the English Aristocracy (1956) is a book edited by Nancy Mitford, illustrated by Osbert Lancaster, caricaturist of English manners, and published by Hamish Hamilton. The anthology comprises four brief essays by Nancy Mitford, Alan S. C. Ross, “Strix” and Christopher Sykes, a letter by Evelyn Waugh, and a poem written by John Betjeman.

Until Nancy Mitford wrote “The English Aristocracy” in an article published in 1955, England was blissfully unconscious of U-Usage. Her article sparked off a public debate, whose counterblasts are collected in this book, published one year later.[1] Although the subtitle rather dryly suggests it as an enquiry into the identifying characteristics of members of the English upper-class, it is really more of a debate, with each essayist entertaining and convincing.

Overview

This collection of essays started with Nancy Mitford's article “The English Aristocracy”, published in 1955 in the magazine Encounter. The expressions “U” (Upper Class) and “Non-U” (non-Upper Class) came to prominence[2] in this article, which sold out the edition of the magazine immediately after publication. The article caused a great deal of light-hearted controversy. The book was published one year later. There is sharp disagreement among the U's who have contributed to this book.Considered one of the most gifted comic writers of her time, Nancy Mitford said she wrote the article about her peers “In order to demonstrate the upper middle class does not merge imperceptibly into the middle class”.[3] She said differences of speech distinguish the members of one social class in England from another. The daughter of a Baron, she was therefore a "Hon" − honourable. Deborah Mitford Cavendish, the Duchess of Devonshire, the youngest of the famously (and sometimes infamously) unconventional Mitford sisters, wrote a letter to Encounter”[4] about the article saying: “... as the co-founder, with my sister Jessica,[5] of the Hons Club, I would like to point out that ... the word Hon meant Hen in Honnish... We were very fond of chickens and on the whole preferred their company to that of human beings[6] ...”.

Editorial Reviews

Noblesse Oblige was received with favourable reviews.

Unabashedly snobbish and devastatingly witty, Miss Mitford achieved enormous success and popularity as one of Britain's most piercing observers of social manners... Indeed, one of Miss Mitford's pet concerns entered the history of obscure literary debates when, in 1955, she published perhaps her most famous essay on upper-class and non-upper- class forms of speech. The essay sparked such a controversy in Britain, with responses from many major literary figures, that Miss Mitford was compelled a year later to bring out a thin book, "Noblesse Oblige," with her disquisition on the subject as its centerpiece.Her argument, a set-piece even today among literary parlor games, was that the more elegant euphemism used for any word is usually the non-upperclass thing to say--or, in Miss Mitford's words, simply non-U. Thus: It is very non-U to say "dentures"; "false teeth" will do. Ill is non-U; sick is U. The non-U person resides at his home. The U person lives in his house. And so forth.

—The New York Times[7]

In these days of penurious peers and vanishing stately homes, how can one tell whether an Englishman is a genuine member of the Upper Class? Last week, in a slim anthology of aristocratic manners edited by aristocratic Novelist Nancy Mitford (Noblesse Oblige; Hamish Hamilton), England got an answer that has managed to stir up everyone from Novelist Graham Greene to Actor John Loder. Not since Humorist Stephen Potter launched the cult of gamesmanship had the nation been so obsessed as it was over the difference between U (Upper Class) and non-U.— Time Magazine[8]

Contents

The English Aristocracy

Nancy Mitford writes in the first essay that the English aristocracy is the only real aristocracy left in the world today, even if it may seem to be on the verge of decadence:[9] it has political power through the House of Lords and real social position through the Queen. Then she explains the order of precedence of dukes, marquesses, earls, viscounts, barons, members of a noble family, young sons, baronets, knights and knights of the Garter. Accused of being a snob, she quotes from Professor Alan Ross of Birmingham University who points out that “it is solely by their language that the upper classes nowadays are distinguished since they are neither cleaner, richer, nor better-educated than anybody else". Miss Mitford says Professor Ross invented the U and non-U English useful formula. Though she doesn't agree completely with the Professor's list, she adopts his classification system, and adds a few suggestions of her own.[10] She gives many examples of U and non-U usage and thoroughly explains the aristocracy saying, for example, dukes are rather new creations, the purpose of the aristocrat is most emphatically not to work for money, and nobility in England is based on title and not on bloodline. The ancestors of the lords spent months abroad, buying pictures and statues, which they cheerfully sell in order to spend months abroad, she writes.

U and Non-U — An Essay in Sociological Linguistics by Alan S. C. Ross

The second article is a condensed and simplified version of Professor Ross’ "Linguistic Class-Indicators in Present-Day English",[11] which appeared in 1954 in the Finnish philological periodical Neuphilologische Mitteilungen. For him the English class-system was essentially tripartite — there exists an upper, a middle, and a lower class. Solely by its language it is possible to identify them. In times past (e.g. in the Victorian and Edwardian periods) this was not the case. In fact the Professor says there are, it is true, a few minor points of life which may serve to demarcate the upper class, but they are minor ones, and he is concerned in this essay only with the linguistic demarcation.[12] This line, for the Professor, is, often, a line between, on one hand, gentlemen and, on the other, persons who, though not gentlemen, must at first sight appear, or would like to appear, as such. Thus, habits of speech peculiar to the lower classes find no place in this article. He also addresses the written language, considering the following points: names on envelopes, etc., beginning of letters, names on cards, postal addresses on envelopes, etc. at the heads of letters, and on cards; finally, letter-endings.

An open letter from Evelyn Waugh

Evelyn Waugh wrote the third contribution, An open letter to the Honble Mrs. Peter Rodd (Nancy Mitford) on a very serious subject from Evelyn Waugh, which also first appeared in Encounter.[13] Widely regarded as a master of style of the 20th century, Waugh, who was a great friend of Nancy Mitford,[14] added his own thoughts to the class debate and points out that Nancy is a delightful trouble maker to write such a thing but also someone who only just managed to be upper class and now resides in another country, so — he asks — who is she really to even bring it all up? Although [15] this may seem offensive, Nancy Mitford said that “everything with Evelyn Waugh was jokes. Everything. That's what none of the people who wrote about him seem to have taken into account at all”.[16]

Posh Lingo by “Strix”

A shorter version of “Strix's” article appeared in The Spectator and this is the fourth essay of the book. “Strix”, pseudonym of Peter Fleming,[17] was a British adventurer and travel writer, who was James Bond author Ian Fleming’s elder brother and a friend of Nancy. He begins saying that Nancy Mitford's article has given rise to much pleasurable discussion. Before pushing on to the less etymological aspects of her theme, he addresses how language evolves and changes naturally,[18] and U-slang, attributing to it a sense of parody. He says interest in the study of U-speech has been arbitrarily awakened and considers this interest unhealthy and contrary to the “national interest”. He closes his article hoping the U-young will strive for a clear, classless medium of communication in which all say “Pardon?” and none say “What?”, and every ball is a dance and every man's wife is “the” wife.

What U-Future? by Christopher Sykes

All groups talk a particular language. Thus begins the fifth essay of the book. It is the natural way of things that you say something one way which the lawyer says another way. Same with doctors. A doctor who can only talk like a text book may leave you in serious doubt as to your state of health, Sykes says. Same with sailors, same with all other craftsmen. Then he comments from Shakespeare, for whom language was a vast instrument at his command, to what he calls the irrational little vocabulary of the movements of fashion: newspaper fashion, pub fashion, cinema fashion, popular song fashion. But, for this English author, the great, the most desired fashion has always been that of “the best society,” of “the fashionable”, of “the chic”, which is kept by snobbism. After further analyzing the use of U and non-U habits and its progress, reflecting either by stress or reaction the mood of any time. Pursuing his argument he introduces Topivity — T-manners and T-customs[19] etc. Abandoning “U”, he ends the article with “T” stating that one big T-point remains constant: nobody wants a really poor peer: it is very un-T not to be rich. However, T and non-T do not seem to have become popular though.

How to get on in society by John Betjeman

The last essay of Noblesse Oblige is a poem taken from A Few Late Chrystanthemums.

“The non-U-ness of fish-knives in place of fish-forks is delightfully satirised by John Betjeman in How to “Get on in Society”(1954):

- Phone for the fish-knives, Norman

- As Cook is a little unnerved;

- You kiddies have crumpled the serviettes

- And I must have things daintily served.

“Some say that the bluntness of a fish-knife reflects its primary function, which is to remove the skin while minimising the risk of cutting the flesh. Others say that the skin is delicious. David Mellor, an authority on cutlery, has pointedly remarked that you don't need a sharp knife to cut fish. He also considers the shape of fish knives to be purely decorative. A standard-shaped knife would do the job better.”

—The Independent.[20]

See also

- Noblesse oblige

- U and non-U English

- Decca; The Letters of Jessica Mitford, Alfred A. Knop .

References

- ↑ Nancy Mitford — Noblesse Oblige

- ↑ Debrett’s

- ↑ Style Weekly — How U are You? by Rosie Right

- ↑ Quoted by Russel Lynes, in his introduction to the first edition of Noblesse Oblige published by Harper & Brothers (1956), in the United States, p. 10

- ↑ Decca — The Letters of Jessica Mitford, Alfred A. Knop

- ↑ The Finantial Times — Life & Arts, Pursuits

- ↑ The New York Times

- ↑ Time Magazine − Education: Who's U? Monday, May 21, 1956

- ↑ the Mitford Society

- ↑ A Penguin a Week — A blog about vintage Penguin paperbacks

- ↑ An Essay in Sociological Linguistics by Alan S. C. Ross — Encounter, November 1955

- ↑ A U and non-U exchange of the upper class — The Independent — Sunday, 5 June 1994

- ↑ Encounter″, December 1955

- ↑ The Letters of Nancy Mitford and Evelyn Waugh — Books, The New York Times

- ↑ The Saturday Review, Denis W. Broughan — July 28, 1956, p. 19

- ↑ Nancy Mitford in a television interview. Quoted in Byrne, p. 348

- ↑ Mitford, 1956 —The University of Hull

- ↑ Savidge Reads

- ↑ Noblesse Oblige, Harper & Brothers (1956), Published in the United States of America, First Edition — What U-Future? ps. 150-156

- ↑ The Independent, Arts and Entertainment — Good Questions: Nothing fishy in the cutlery drawer at Buckingham Palace