Nilotic landscape

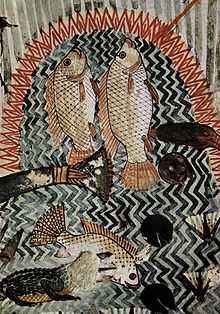

Nilotic landscape is any artistic representation of landscapes that emulates or is inspired by the Nile river in Egypt. The term was coined to refer primarily to such landscapes created outside of Egypt, especially in the Aegean, though it is occasionally used to refer to scenes of hunting and fishing in Egyptian art. A nilotic landscape is a river scene with rich and abundant plant and animal life, much of which is native to Egypt. Common iconographic elements include papyrus, palm trees, fish and water birds, and in some cases felines, monkeys, and/or crocodile.

.jpg)

Archaeological evidence attests to painted depictions of the Nile in Egyptian tombs as early as the Predynastic period. Nilotic scenes remain popular throughout the Old and Middle Kingdoms, and flourish in the New Kingdom. Of particular prominence are landscapes in tombs paintings of the 18th dynasty of Egypt. Nilotic landscapes are first adapted outside of Egypt in the Aegean, notably in the art of the Minoan civilization. The motif enjoys a renaissance in the Roman Empire, when nilotic scenes become a common subject for mosaics.

The production of nilotic landscapes as well as their iconography and interpretations depend on the provenance of the work and the culture in which it was produced, but most scenes on the whole affirm and celebrate the abundance of nature.

Iconography

The most important feature of a nilotic landscape is its riverine setting, which is the ultimate source of any accompanying plant and animal life. The annual flooding of the Nile river in Egypt was not only the source of the ancient civilization’s food and crops, but also provided them with a dependable cyclical calendar. Much of Egypt’s continuity in antiquity, both in society and in art, is thought to stem from the people’s relationship to the Nile.

Nilotic landscapes are filled with abundant plant and animal life. Blue and green pigments often dominate the scene. The papyrus plant and palm trees are the most recognizable botanic features of a nilotic landscape, along with other plants, often carefully depicted and identifiable. Various animals are represented and vary depending on the specific scene. Many varieties of fish and water birds are found in the scenes, and hunting and fishing scenes usually include cats. Other nilotic landscapes, especially those outside of Egypt, include exotic, foreign animals, such as monkeys and crocodiles, and often fantastic creatures or monsters like griffins and sphinxes.

Nilotic landscapes in Egypt

The phrase "nilotic landscape" is used in Egyptian studies to describe the scenes in tomb paintings where the deceased is engaged in hunting and fishing. These scenes stress the elite character and importance of the deceased, who conquers nature and dominates the landscape, participating in activities reserved for the upper class.[1] Many scenes are symmetrical, with the image of the deceased repeated, first engaged in the act of hunting birds and then spearing fish. The birds and fish often appear in large numbers. They are easily captured by the deceased as they appear to literally fly around him or swim right up to his spear. Thus man is shown in a position of control over nature and the natural world as subservient to his own existence.

Though these scenes have a centuries old tradition, they become increasingly popular in the 18th dynasty of the New Kingdom, with prominent examples of these scenes discovered in tombs from the necropolis of ancient Thebes in the Valley of the Kings.[2] Artistically the scenes are characterized by a sense of movement and liveliness not normally seen in most Egyptian works, which for centuries portrayed static, stoic figures and creatures.[3] There is ample attention paid to detail discernible in the realistic rendering of individual plant and animal species. Variety is imparted by means of these careful details and individualized characterizations.

Nilotic Landscapes in the Aegean

River scenes suggesting the natural world and its lush vegetation begin to appear outside of Egypt contemporaneously with the 18th dynasty, the first extant evidence coming from fresco fragments of the Minoans. The Aegean version of the nilotic landscape retains many key iconographic elements of the Egyptian version, but the Minoans often make the landscape itself the subject, emphasizing plants and wildlife over human figures (which are generally left out of the work). The compositions are characteristic of the Minoan artistic style, more irregular and informal. Attention is paid to detail and color with respect to plants and animals, but precisely drawn patterns seldom arise and the background and setting may be highly imaginative. They are true frescoes, painted on wet plaster so that the color chemically adheres to the surface, unlike the Egyptian versions.

Nilotic landscapes in Minoan art are evidence of contact between the Minoans and the Egyptians, both through trade and the exchange of ideas. Plants like papyrus and animals like monkeys were not native to Crete. Many of the plant and animal species are identifiable, confirming not only that the artists paid close attention to detail, but also that they must have been familiar with these species, either through examination of Egyptian painting or, as seems more likely, by means of direct contact with these creatures, plants, and Egyptian culture.[4]

At the “House of the Frescoes”, located near the Minoan palace at Knossos, fresco fragments were unearthed depicting blue monkeys and blue birds in a rocky landscape with a winding blue river, along with various types of plants, including papyrus.[5] This scene has been dubbed a “nilotic landscape” by archaeologists and art historians due to its inclusion of blue monkeys and papyrus in a riverine setting.

Excavations at Akrotiri on the island of Thera have preserved a number of frescoes dating to the Late Bronze Age. One such scene from the "West House" on the east wall of Room 5 has been termed a nilotic landscape. It features a mix of real and imaginary creatures. A griffin flies over the meandering river, a wild cat stalks ducks, and palm trees pervade. Unlike the two other fresco scenes in this room, the nilotic landscape is devoid of human figures and lacks narrative, focusing instead on the wildlife and environment and glorifying the natural world.[6] The absence of human figures in these Minoan nilotic landscapes has led many archaeologists to assume the presence of a nature goddess or divinity in Minoan religion.[7]

Mosaic landscape from Praeneste

It is within this long-established tradition that the late Hellenistic Nile mosaic of Palestrina (ancient Praeneste) has to be understood.

Further reading

- Betancourt, Philip P. (2007). Introduction to Aegean Art. Philadelphia: INSTAP Academic Press. (hardcover, ISBN 1-931534-21-7)

- Davies, W. Vivian and Louise Schofield. (1995). Egypt, the Aegean, and the Levant: Interconnections in the Second Millennium BC. London: British Museum Press (hardcover, ISBN 0-7141-0987-8)

- Immerwahr, Sarah. (1988). "A Possible Influence of Egyptian Art in the Creation of Minoan Wall Painting,” in L’Iconographie Minoenne (Bulletin de Correspondance Hellénique, Supplement 11), O. Picard, ed., Athens, pp. 41–50 (hardcover, ASIN B000J0E7B4)

- Immerwahr, Sarah. (1990). Aegean Painting in the Bronze Age. University Park: Penn State University Press (hardcover, ISBN 0-271-00628-5)

- Tiradritti, Francesco. (2007). Egyptian Wall Painting. New York: Abbeville Publishing Group (hardcover, ISBN 0-7892-1005-3)

- Versluys, M.J. (2002). Aegyptiaca Romana: nilotic scenes and the Roman views of Egypt. Boston: Brill Publishing (hardcover, ISBN 90-04-12440-3)

References

- ↑ Tiradritti, Francesco. (2007). Egyptian Wall Painting. New York: Abbeville Publishing Group (hardcover, ISBN 0-7892-1005-3)

- ↑ Examples include: Hunting in the marsh, a fragment of painted plaster from the tomb of Nebamun, Hunting and Fishing in the marsh, painted plaster from the tomb of Nakht, and Hunting and Fishing in the marsh, Painted plaster from the tomb of Menna)

- ↑ Kleiner, Fred S. and Christin J. Mamiya. (2004). Gardner's Art through the Ages, Vol. 1. Belmont: Wadsworth Publishing (hardcover, ISBN 0-534-64095-8)

- ↑ Davies, W. Vivian and Louise Schofield. (1995). Egypt, the Aegean, and the Levant: Interconnections in the Second Millennium BC. London: British Museum Press (hardcover, ISBN 0-7141-0987-8)

- ↑ Evans, Arthur. (1936). The Palace of Minos at Knossos, I-IV. London: Macmillan and Co.

- ↑ Doumas, Cristos. (1983) Thera. Pompeii of the ancient Aegean. Excavations at Akrotiri, 1967-79. London: Thames and Hudson Ltd (hardcover, ISBN 0-500-39016-9)

- ↑ Marinatos, Nanno. (1993). Minoan Religion: Ritual, Image, and Symbol. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press (hardcover, ISBN 0-87249-744-5)