Nighthawks

| |

| Artist | Edward Hopper |

|---|---|

| Year | 1942 |

| Type | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions | 84.1 cm × 152.4 cm (33 1⁄8 in × 60 in) |

| Location | Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois |

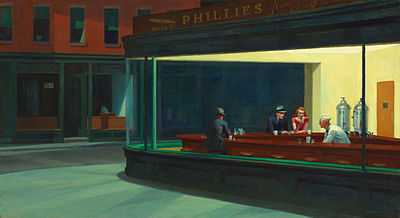

Nighthawks is a 1942 oil on canvas painting by Edward Hopper that portrays people in a downtown diner late at night.

It is Hopper's most famous work[1] and is one of the most recognizable paintings in American art.[2][3] Within months of its completion, it was sold to the Art Institute of Chicago for $3,000[4][5] and has remained there ever since.

About the painting

Josephine Hopper's notes on the painting

Starting shortly after their marriage in 1924, Edward Hopper and his wife Josephine (Jo) kept a journal in which he would, using a pencil, make a sketch-drawing of each of his paintings, along with a precise description of certain technical details. Jo Hopper would then add additional information about the theme of the painting.

A review of the page on which Nighthawks is entered shows (in Edward Hopper's handwriting) that the intended name of the work was actually Night Hawks and that the painting was completed on January 21, 1942.

Jo's handwritten notes about the painting give considerably more detail, including the possibility that the painting's title may have had its origins as a reference to the beak-shaped nose of the man at the bar:

Night + brilliant interior of cheap restaurant. Bright items: cherry wood counter + tops of surrounding stools; light on metal tanks at rear right; brilliant streak of jade green tiles 3/4 across canvas--at base of glass of window curving at corner. Light walls, dull yellow ocre [sic] door into kitchen right.Very good looking blond boy in white (coat, cap) inside counter. Girl in red blouse, brown hair eating sandwich. Man night hawk (beak) in dark suit, steel grey hat, black band, blue shirt (clean) holding cigarette. Other figure dark sinister back--at left. Light side walk outside pale greenish. Darkish red brick houses opposite. Sign across top of restaurant, dark--Phillies 5c cigar. Picture of cigar. Outside of shop dark, green. Note: bit of bright ceiling inside shop against dark of outside street--at edge of stretch of top of window.[6]

In January 1942, Jo confirmed her preference for the name. In a letter to Edward's sister Marion she wrote, "Ed has just finished a very fine picture--a lunch counter at night with 3 figures. Night Hawks would be a fine name for it. E. posed for the two men in a mirror and I for the girl. He was about a month and half working on it."[7]

Description

The themes that may or may not be embedded in Nighthawks are ambiguous, but viewers can also appreciate the painting from a purely technical point of view.

As a starting-point, there is Jo Hopper’s journal entry. Additionally, a careful viewer will notice the unusual use of perspective, color, and light in the painting.

Perspective

Hopper chose to paint a scene located at a sharply angled street-corner rather than at one of New York’s many right-angled intersections. This choice was not unusual for Hopper who painted a number of other scenes of this kind of corner (see August in the City and Office at Night (1940)). A sharp corner gave him the opportunity to display his subjects from a nearly frontal point of view and also allowed him to display the dimly visible street scene behind the patrons. Hopper often painted scenes in which a part of the exterior view could be seen through two panes of glass (see Office in a Small City (1953), Railroad Sunset (1929) and Cape Cod Morning (1950)). But the shape of the diner in Nighthawks, when seen from Hopper’s chosen angle (which is also the point of view of a passer-by walking past on the sidewalk), allows this second glass surface to fill the entire centre of the painting. The further pane of glass forms a rhomboid close to the center of the painting that recalls, with slight distortion, the shape of the entire canvas while framing much of the action.

The back window serves as a background for all three customers but not for the server. Its variance from the shape of the painting as a whole also hides a curious symmetry that would otherwise be obvious: The head of the customer who is sitting alone is at the center of the frame-within-a-frame (which is also the center of the painting as a whole). Although they sit around a bend in the counter, the heads of the couple are directly to his right, so that a horizontal line, drawn halfway between the top and the bottom of the canvas, would bisect all three heads. The entire human element in the painting is therefore contained within the lower right-hand quarter of the canvas.

Color

As Jo Hopper's journal entry notes, the brightest spot in the painting is the "bit of bright ceiling" close to the hidden fluorescent light that illuminates the interior. The ceiling is obviously of limited relevance to any narrative that might be unfolding among the customers below; this is Hopper’s realism at work.

Outside the diner, dull colors predominate, as might be expected at night. Inside, the counter-top and the men’s suits are also dull. The two brightly colored spots in the entire interior are the white outfit worn by the server and the female customer’s red blouse. Indeed, her red blouse and lipstick represent the only use of red in the entire composition, causing her to stand apart from everything else in the painting.

Light

Hopper had a lifelong interest in capturing the effect of light on the objects it touched. This interest extended to his numerous canvases of sunlit houses and lighthouses in New England but he was equally intrigued by the nighttime effect of manmade light spilling out of windows, doorways and porches; he returned to this subject of artificial light over and over again in paintings like Drug Store (1927), Gas (1940), Rooms for Tourists (1945) and Summer Evening (1947).

However, Nighthawks is probably Hopper’s most ambitious effort in capturing the night-time effects of manmade light. For one, the diner’s plate-glass windows cause far more light to spill out onto the sidewalk and the brownstones on the far side of the street than in any of his other paintings. This interior light comes from more than a single lightbulb, thereby casting multiple different shadows, and some spots are brighter than others as a result of being lit from more than one angle. Across the street, the line of shadow caused by the upper edge of the diner window is clearly visible towards the top of the painting. These windows, and the ones below them, are partly lit by an unseen streetlight which projects its own mix of light and shadow. As a final note, the bright interior light causes some of the surfaces within the diner to be reflective. This is clearest in the case of the right-hand edge of the rear window which reflects a vertical yellow band of interior wall, but fainter reflections can also be made out, in the counter-top, of three of the diner’s occupants. None of these reflections would be visible in daylight.

Possible inspirations

Hopper's biographer, Gail Levin, speculates that Hopper may have been inspired by Vincent Van Gogh's "sinister Night Café"[8] which was showing at a gallery in New York in January 1942. The similarity in lighting and themes makes this possible; it is certainly unlikely that Hopper would have failed to see the exhibition, and as Levin notes, the painting had twice been exhibited in the company of Hopper's own works. Beyond this, there is no evidence that The Night Café exercised an influence on Nighthawks. Although there is no evidence at all (other than the fact that Hopper admired the story), Levin also suggests that he may have been inspired by Ernest Hemingway's 1927 short story, The Killers.[8]

Searching for the location of the restaurant

The scene was supposedly inspired by a diner (since demolished) in Greenwich Village, Hopper's neighborhood in Manhattan. Hopper himself said the painting "was suggested by a restaurant on Greenwich Avenue where two streets meet." Additionally, he noted that "I simplified the scene a great deal and made the restaurant bigger."[9]

This reference has led Hopper aficionados to engage in a search for the location of the original diner. The inspiration for this search has been summed up on the blog of one of these searchers: "I am finding it extremely difficult to let go of the notion that the Nighthawks diner was a real diner, and not a total composite built of grocery stores, hamburger joints, and bakeries all cobbled together in the painter's imagination."[10]

The spot usually associated with the former location is a now-vacant lot known as Mulry Square at the intersection of Seventh Avenue South, Greenwich Avenue and West 11th Street, about seven blocks west of Hopper's studio on Washington Square. However, according to an article by Jeremiah Moss in The New York Times, this cannot be the location of the diner that inspired the painting as a gas station occupied that lot from the 1930s to the 1970s.[11]

Moss located a land-use map in a 1950s municipal atlas showing that "Sometime between the late '30s and early '50s, a new diner appeared near Mulry Square." Specifically, the diner was located immediately to the right of the gas station, "not in the empty northern lot, but on the southwest side, where Perry Street slants." This map is not reproduced in the Times article but is shown on Moss's blog.[12]

Moss comes to the conclusion that Hopper should be taken at his word: the painting was merely "suggested" by a real-life restaurant, he had "simplified the scene a great deal," and he "made the restaurant bigger." In short, there probably never was a single real-life scene identical to the one that Hopper had created, and if one did exist, there is no longer sufficient evidence to pin down the precise location. Moss concludes, "the ultimate truth remains bitterly out of reach."[10]

In popular culture

Because it is so widely recognized, the diner scene in Nighthawks has served as the model for many homages and parodies.

Painting and sculpture

Many artists have produced works that allude or respond to Nighthawks. An early example is George Segal's sculpture The Diner (1964–1966), made from parts of a real diner with Segal's white plaster figures added, which resembles Nighthawks in its sense of loneliness and alienation as well as in its subject matter. Roger Brown, one of the Chicago Imagists, included a view into a corner cafe in his painting Puerto Rican Wedding (1969), a stylized nighttime street scene.

Hopper influenced the Photorealists of the late 1960s and early 1970s, including Ralph Goings, who evoked Nighthawks in several paintings of diners. Richard Estes painted a corner store in People's Flowers (1971), but in daylight, with the shop's large window reflecting the street and sky.[14]

More direct visual quotations began to appear in the 1970s. Gottfried Helnwein's painting Boulevard of Broken Dreams (1984) replaces the three patrons with American pop culture icons Humphrey Bogart, Marilyn Monroe and James Dean, and the attendant with Elvis Presley.[15] According to Hopper scholar Gail Levin, Helnwein connected the bleak mood of Nighthawks with 1950s American cinema and with "the tragic fate of the decade's best-loved celebrities."[16] Greenwich Avenue (1986), one of several parodies painted by Mark Kostabi, increases the painting's scale and uses a palette of garish electric colors; the human figures are red and faceless. Nighthawks Revisited, a 1980 parody by Red Grooms, clutters the street scene with pedestrians, cats and trash.[17] A 2005 Banksy parody shows a fat, shirtless soccer hooligan in Union Flag boxers standing inebriated outside the diner, apparently having just smashed the diner window with a nearby chair.[18]

Literature

Several writers have explored how the customers in Nighthawks came to be in a diner at night, or what will happen next. Wolf Wondratschek's poem "Nighthawks: After Edward Hopper's Painting" imagines the man and woman sitting together in the diner as an estranged couple: "I bet she wrote him a letter/ Whatever it said, he's no longer the man / Who'd read her letters twice."[19] Joyce Carol Oates wrote interior monologues for the figures in the painting in her poem "Edward Hopper's Nighthawks, 1942".[20] A special issue of Der Spiegel included five brief dramatizations that built five different plots around the painting; one, by screenwriter Christof Schlingensief, turned the scene into a chainsaw massacre. Erik Jendresen also wrote a short story inspired by this painting.[21]

Film

Hopper was an avid moviegoer and critics have noted the resemblance of his paintings to film stills. Several of his paintings suggest gangster films of the early 1930s such as Scarface and Little Caesar, a connection that can be seen in the clothes of the customers in the diner. Nighthawks and works such as Night Shadows (1921) anticipate the look of film noir whose development Hopper may have influenced.[22][23] Nighthawks was briefly featured in the 1986 John Hughes comedy, Ferris Bueller's Day Off in the art gallery scene.

Hopper was an acknowledged influence on the film musical Pennies from Heaven (1981), in which director Ken Adams recreated Nighthawks as a set.[24] Director Dario Argento went so far as to recreate the diner and the patrons in Nighthawks as part of a set for his 1976 film Deep Red. Director Wim Wenders recreated Nighthawks as the set for a film-within-a-film in The End of Violence (1997).[22] Wenders suggested that Hopper's paintings appeal to filmmakers because "You can always tell where the camera is."[25] In Glengarry Glen Ross (1992), two characters visit a café resembling the diner in a scene that illustrates their solitude and despair.[26] Hard Candy (2005) acknowledged the debt by setting one scene at a "Nighthawks Diner" where a character purchases a T-shirt with Nighthawks printed on it.[27] The painting was also briefly used as a background for a scene in the animated film Heavy Traffic (1973) by director Ralph Bakshi.

Nighthawks also influenced the "future noir" look of Blade Runner; director Ridley Scott said "I was constantly waving a reproduction of this painting under the noses of the production team to illustrate the look and mood I was after".[28] In his review of Alex Proyas' Dark City, Roger Ebert noted that the film had "store windows that owe something to Edward Hopper's Nighthawks."[29]

Music

- Tom Waits's album Nighthawks at the Diner (1975) features Nighthawks-inspired lyrics.[30]

- The video for Voice of the Beehive's song "Monsters and Angels", from Honey Lingers, is set in a diner reminiscent of the one in Nighthawks, with the band-members portraying waitstaff and patrons. The band's web site said they "went with Edward Hopper's classic painting, Nighthawks, as a visual guide."[31]

- Orchestral Manoeuvres in the Dark's 2013 single "Night Café" was influenced by Nighthawks and mentions Hopper by name. Seven of his paintings are referenced in the lyrics.[32]

Television

- The television series CSI: Crime Scene Investigation placed its characters in a version of the painting.[33]

- In the That '70s Show episode "Drive In," a scene ends with Red and Kitty Foreman sitting in a diner named "Phillies", when Kitty states that the moment seems familiar. The camera zooms out showing Nighthawks with Red and Kitty wearing the suit and red dress, respectively, of the man and woman sitting together.[34]

- In the TV show Dead Like Me (Season 1 - Episode 12 - "Nighthawks") The painting is discussed in a diner by the two lead actors while they are looking at an image of it in a book of art. There are two customers in the diner who resemble the woman in the red dress and her partner from the painting and the final scene of the show echoes the composition of the painting.

- In the "Mike Tyson Mysteries" episode "Night Moves" (Season one Episode nine) the ending credits play over a variation on the painting featuring the characters of the show.

- In 2015 an American Family Insurance commercial featuring Jennifer Hudson was set in a diner with characters taken from the painting.

Scale model

Electronic Theatre Controls (ETC) in Middleton, Wisconsin pays tribute to Nighthawks with an entirely scale model representation of the scene in their lobby. The lunch counter is used as the receptionist's desk.

Parodies

Nighthawks has been widely referenced and parodied in popular culture. Versions of it have appeared on posters, T-shirts and greeting cards as well as in comic books and advertisements.[35] Typically, these parodies—like Helnwein's Boulevard of Broken Dreams, which became a popular poster[16]—retain the diner and the highly recognizable diagonal composition but replace the patrons and attendant with other characters: animals, Santa Claus and his reindeer, or the cast of The Adventures of Tintin or Peanuts.[36]

- One parody of Nighthawks even inspired a parody of its own. Michael Bedard's painting Window Shopping (1989), part of his Sitting Ducks series of posters, replaces the figures in the diner with ducks and shows a crocodile outside eying the ducks in anticipation. Poverino Peppino parodied this image in Boulevard of Broken Ducks (1993), in which a contented crocodile lies on the counter while four ducks stand outside in the rain.[37]

- At the end of most episodes of the animated series The Tick, Tick and Arthur are shown in a setting similar to Nighthawks. The painting was also used in The End of Silliness?.

- In 2014, Sirius Radio host Howard Stern, featured a parody on his website entitled Wack Pack Diner.[38] It was displayed after the passing of Eric the Actor, one of Stern's longtime featured guest personalities.

Ownership history

Upon completing the canvas in the late winter of 1942, Hopper placed it on display at Rehn's, the gallery at which his paintings were normally placed for sale. It remained there for about a month. On St. Patrick's Day, Edward and Jo Hopper attended the opening of an exhibit of the paintings of Henri Rousseau at the Museum of Modern Art, which had been organized by Daniel Catton Rich, the director of the Art Institute of Chicago. Rich was in attendance, along with Alfred Barr, the director of the Museum of Modern Art. Barr spoke enthusiastically of Gas, which Hopper had painted a year earlier, and "Jo told him he just had to go to Rehn's to see Nighthawks. In the event it was Rich who went, pronounced Nighthawks 'fine as a Homer', and soon arranged its purchase for Chicago."[39] The sale price was $3,000, equivalent to approximately $42,900 in 2013.[5] The painting has remained in the collection of the Art Institute ever since.

References

Notes

- ↑ Ian Chilvers and Harold Osborne (Eds.), The Oxford Dictionary of Art Oxford University Press, 1997 (second edition), p. 273, ISBN 0-19-860084-4 "The central theme of his work is the loneliness of city life, generally expressed through one or two figures in a spare setting - his best-known work, Nighthawks, has an unusually large 'cast' with four."

- ↑ Hopper's Nighthawks, Smarthistory video, accessed April 29, 2013.

- ↑ Brooks, Katherine (2012-07-22). "Happy Birthday, Edward Hopper!". The Huffington Post. TheHuffingtonPost.com, Inc. Retrieved 2013-05-05.

- ↑ The sale was recorded by Josephine Hopper as follows, in volume II, p. 95 of her and Edward's journal of his art: "May 13, '42: Chicago Art Institute - 3,000 + return of Compartment C in exchange as part payment. 1,000 - 1/3 = 2,000." See Deborah Lyons, Edward Hopper: A Journal of His Work. New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, 1997, p. 63.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 approximately $42,900 in 2013 – "Measuring Worth". Retrieved 2014-05-18.

- ↑ See Deborah Lyons, Edward Hopper: A Journal of His Work. New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, 1997, p. 63

- ↑ Jo Hopper, letter to Marion Hopper, January 22, 1942. Quoted in Gail Levin, Edward Hopper: An Intimate Biography. New York: Rizzoli, 2007, p. 349.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Gail Levin, Edward Hopper: An Intimate Biography. New York: Rizzoli, 2007, p. 350.

- ↑ Hopper, interview with Katharine Kuh, in The Artist's Voice: Talks with Seventeen Modern Artists. 1962. Reprinted, New York: Da Capo Press, 2000, p. 134.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Jeremiah Moss (2010-06-10). "Jeremiah's Vanishing New York: Finding Nighthawks, Coda". Vanishing New York. Retrieved 2013-03-04.

- ↑ Moss, Jeremiah (July 5, 2010). "Nighthawks State of Mind". The New York Times. Retrieved May 22, 2013.

- ↑ Moss, Jeremiah (June 9, 2010). "Finding Nighthawks, Part 3". Jeremiah's Vanishing New York (blog). Retrieved May 18, 2014.

- ↑ Levin, 111–112.

- ↑ Levin, Gail (1995), "Edward Hopper: His Legacy for Artists", in Lyons, Deborah; Weinberg, Adam D., Edward Hopper and the American Imagination, New York: W. W. Norton, pp. 109–115, ISBN 0-393-31329-8

- ↑ "Boulevard of Broken Dreams II". Helnwein.com. 2013-10-15. Retrieved 2014-08-18.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Levin, 109–110.

- ↑ Levin, 116–123.

- ↑ Jury, Louise (October 14, 2005), "Rats to the Arts Establishment", The Independent

- ↑ Gemünden, 2–5, 15; quotation translated from the German by Gemünden.

- ↑ Updike, John (2005), Still Looking: Essays on American Art, New York: Knopf, p. 181, ISBN 1-4000-4418-9 . The Oates poem appears in the anthology Hirsch, Edward, ed. (1994), Transforming Vision: Writers on Art, Chicago, Illinois: Art Institute of Chicago, ISBN 0-8212-2126-4

- ↑ Gemünden, 5–6.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Gemünden, Gerd (1998), Framed Vsions: Popular Culture, Americanization, and the Contemporary German and Austrian Imagination, Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, pp. 9–12, ISBN 0-472-10947-2

- ↑ Doss, Erika (1983), "Edward Hopper, Nighthawks, and Film Noir" (PDF), Post Script: Essays in Film and the Humanities 2 (2): 14–36

- ↑ Doss, 36.

- ↑ Berman, Avis (2007), "Hopper", Smithsonian 38 (4): 4

- ↑ Arouet, Carole (2001), "Glengarry Glen Ross ou l’autopsie de l’image modèle de l’économie américaine" (PDF), La Voix du Regard (14)

- ↑ Chambers, Bill, "Hard Candy (2006), The King (2006)", Film Freak Central, retrieved 2007-08-05

- ↑ Sammon, Paul M. (1996), Future Noir: the Making of Blade Runner, New York: HarperPrism, p. 74, ISBN 0-06-105314-7

- ↑ http://www.ebertfest.com/two/dark_city_rev.htm

- ↑ Thiesen, 10; Reynolds, E25.

- ↑ "The Beehive – Voice of the Beehive Online – Biography". Retrieved 20 August 2010.

- ↑ "Premiere: OMD, 'Night Café' (Vile Electrodes 'B-Side the C-Side' Remix)". Slicing Up Eyeballs. 5 August 2013. Retrieved 25 September 2013.

- ↑ Theisen, Gordon (2006), Staying Up Much Too Late: Edward Hopper's Nighthawks and the Dark Side of the American Psyche, New York: Thomas Dunne Books, p. 10, ISBN 0-312-33342-0

- ↑ Reynolds, E25. The episode is #108, "Drive In".

- ↑ Levin, 125–126. Reynolds, Christopher (September 23, 2006), "Lives of a Diner", Los Angeles Times: E25

- ↑ Levin, 125–126; Thiesen, 10.

- ↑ Müller, Beate (1997), "Introduction", Parody: Dimensions and Perspectives, Rodopi, ISBN 904200181X

- ↑ http://www.sirius.comwww.howardstern.com/uploads/FanZoneDownloadModel/87/image/broken-dreams-copy.original.jpg

- ↑ Gail Levin, Edward Hopper: An Intimate Biography. New York: Rizzoli, 2007, pp. 351-2, citing Jo Hopper's diary entry for March 17, 1942.

Bibliography

- Cook, Greg, "Visions of Isolation: Edward Hopper at the MFA", Boston Phoenix, May 4, 2007, p. 22, Arts and Entertainment.

- Spring, Justin, The Essential Edward Hopper, Wonderland Press, 1998

External links

- Nighthawks at The Art Institute of Chicago

- Sister Wendy's American Masterpieces discussion of Nighthawks at The Artchive.

- Jeremiah Moss (7 June 2010). "Finding Nighthawks". Jeremiah's Vanishing New York.

| ||||||