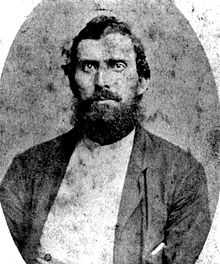

Newton Knight

| Newton Knight | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

November 1837[1]:243 Jones County, Mississippi, United States |

| Died |

February 16, 1922 Jasper County, Mississippi |

Resting place | Knight Cemetery, Jasper County, Mississippi[2] |

| Occupation | Farmer |

Political party | Republican[3] |

| Religion | Primitive Baptist[3] |

Newton Knight (November 1837 – February 16, 1922) was an American farmer, soldier and Southern Unionist, best known as the leader of the Knight Company, a band of Confederate Army deserters that turned against the Confederacy during the Civil War. Local legends state that Knight and his men attempted to form the "Free State of Jones" in the area around Jones County, Mississippi, at the height of the war.

After the war, Knight aided Mississippi's Reconstruction government. Knight has long been a controversial figure. Historians and descendants disagree over his motives and actions, with some arguing he was a noble and pious individual who refused to fight for a cause in which he did not believe, while others have portrayed him as a manipulative outlaw. This controversy was fueled in part by Knight's common-law marriage to a former slave, which effectively established a small mixed-race community in southeastern Mississippi.[4] The marriage would have been considered illegal as Mississippi banned interracial marriages except from 1870–1880 during Reconstruction.

The 1942 James H. Street novel, Tap Roots, was inspired by Knight's actions in the Civil War. The novel was the basis for the 1948 film of the same name, which was directed by George Marshall. The film ignored the interracial aspect, instead casting the tension as one of class.

Early life

Knight was born in Jones County, Mississippi, in November 1837. There has been confusion over his age, as his son, Tom Knight, wrote that he was born in 1830, and his grandniece, Ethel Knight, stated he was born in 1829. The 1900 census states that Knight was born in November 1837, which is supported by census records from other years.[1]:243[5]

Newton was a grandson of John "Jackie" Knight (1773–1861), one of Jones County's largest slaveholders.[1]:62 Newton's father, Albert (1799–1862), however, did not own any slaves, and was the only child of Jackie Knight who did not inherit any.[6] Newton, likewise, did not own any slaves.[1]:64 Some say he was morally opposed to slavery due to his Primitive Baptist beliefs, which also caused Newton to forswear alcohol, unlike his father and grandfather. [3] He was probably taught to read and write by his mother.[1]:85

Newton Knight married Serena Turner in 1858, and the two established a small farm just across the county line in Jasper County.[3]

Civil War

Knight, like many Jones Countians, was opposed to secession. The county elected John H. Powell, the "cooperation" (anti-secession) candidate, to represent them at Mississippi's secession convention in January 1861. When he arrived in Jackson Powell found there was no opportunity to vote against secession, there were only two issues; both of which delayed secession until other states had seceded. Powell voted against immediate secession on the first ballot, but that option failed. Left with no other choice he signed the Declaration of Secession. In an interview many years later, Knight suggested many Jones Countians, unaware of how few options he had, felt betrayed by Powell.[4][7]

Knight enlisted in the Confederate Army in July 1861 (though he would have been drafted anyway). He was given a furlough in January 1862, however, to return home and tend to his ailing father, but never returned to his unit. In May 1862, Knight, along with a number of friends and neighbors, enlisted in Company F of the 7th Battalion, as they preferred to serve together in the same company, rather than with strangers.[1]:99

Throughout the summer and fall of 1862, a number of factors prompted desertions by Jones Countians serving in the Confederate Army. One factor was the lack of food and supplies in the aftermath of the Siege of Corinth. Another involved reports of poor conditions back home, as small farms deteriorated from neglect. Knight was enraged when he received word that Confederate authorities had seized his family's horse. However, many believe Knight's principal reason for desertion was his outrage over the Confederate government's passing of the Twenty Negro Law. This act allowed wealthy plantation owners to avoid military service if they owned twenty slaves or more. An additional family member was exempted from service for each additional twenty slaves owned. Knight had also received word that his brother-in-law, Bill Morgan, who had become the head of the family in Knight's absence, was abusing his children.[1]:100–101 Morgan's identity has since been lost, but it is thought to be Morgan Lines, a day laborer and convicted murderer.[8]

Knight was reported AWOL in October 1862. He later defended his desertion, arguing, "if they had a right to conscript me when I didn't want to fight the Union, I had a right to quit when I got ready."[4] After returning home having deserted in the retreat following the defeat at Corinth, Knight, according to relatives, shot and killed Morgan.[1]:100

In early 1863, Knight was arrested and jailed, and possibly tortured, by Confederate authorities for desertion.[9] His homestead and farm were destroyed, leaving his family destitute. [1]:104[10]

As the ranks of deserters swelled in the aftermath of the Siege of Vicksburg, Confederate authorities began receiving reports that deserters in the Jones County area were looting houses. General Braxton Bragg dispatched Major Amos McLemore to Jones County to investigate and round up deserters and stragglers. On October 5, 1863, McLemore was shot and killed in the Ellisville home of Amos Deason, and Knight was believed to have pulled the trigger.[3]

On October 13, 1863, the Knight Company, as it was called, a band of guerillas from Jones County and the adjacent counties of Jasper, Covington, Perry and Smith, was organized to protect the area from Confederate authorities.[4] Knight was elected "captain" of the company, which included many of his relatives and neighbors.[11] The company's main hideout, known as "Devils Den," was located along the Leaf River at the Jones-Covington county line. Local women and slaves provided food and other aid to the men. Women blew cattlehorns to signal the approach of Confederate authorities.[1]:112

From late 1863 to early 1865, the Knight Company allegedly fought fourteen skirmishes with Confederate forces. One skirmish took place on December 23, 1863, at the home of Sally Parker, a Knight Company supporter, leaving one Confederate soldier dead and two badly wounded.[1]:107 During this same period, Knight led a raid into Paulding, where he and his men captured five wagonloads of corn, which they distributed among the local population.[1]:112 The company harassed Confederate officials, with numerous tax collectors, conscript officers, and other officials being reported killed in early 1864.[3] In March 1864, the Jones County court clerk notified the governor that guerillas had made tax collections in the county all but impossible.[1]:112

By the spring of 1864, the Confederate government in the county had been effectively overthrown.[3] Lieutenant General Leonidas Polk wrote Jefferson Davis on March 21, 1864, describing the Unionism in Jones County. Jones Countians, he stated, were “in open rebellion, defiant at the outset, proclaiming themselves ‘Southern Yankees,’ and resolved to resist by force of arms all efforts to capture them.”[12] On March 29, 1864, Confederate Captain Wirt Thomson wrote James Seddon, Confederate Secretary of War, claiming the Knight Company had captured Ellisville and raised the Union flag over the courthouse in Jones County. He further reported, “The country is entirely at their mercy.”[13] General William T. Sherman had received a letter from a local group declaring its independence from the Confederacy.[3] In July 1864, the Natchez Courier reported that Jones County had seceded from the Confederacy.[4]

General Polk initially responded to the actions of the Knight Company by sending a contingent under Colonel Henry Maury into the area in February 1864. Maury reported he had cleared the area, but noted the deserters had threatened to obtain "Yankee aid" and return.[4] Shortly afterward, Polk dispatched a veteran contingent of soldiers led by Colonel Robert Lowry, a future governor who would later describe Knight as an "ignorant and uneducated man."[14] Using bloodhounds to track down guerillas in the swamps, Lowry rounded up and executed ten members of the Knight Company, including Newton's cousins, Benjamin Franklin Knight and Sil Coleman. Newton Knight, however, evaded capture. He later stated his company had unsuccessfully attempted to break through Confederate lines to join the Union Army.[4]

Reconstruction and later life

At the end of the war, the Union Army tasked Knight with distributing food to struggling families in the Jones County area. He also led a raid that liberated several children who were still being held in slavery in a nearby county.[3] Like many Southern Unionists, he supported the Republican Party, namely the Reconstruction administration of Governor Adelbert Ames. As conflict mounted between the white Confederate resistance (the Ku Klux Klan) and the Reconstruction government, Ames appointed Knight Colonel of the First Infantry Regiment of Jasper County, an otherwise all black regiment defending against Klan activity. After the Southern Democrats regained control of the state government, he withdrew from politics.[3]

In 1870, Knight petitioned the federal government for compensation for several members of the Knight Company, including the ten who had been executed by Lowry in 1864. He provided sworn statements from several individuals attesting to his loyalty to the Union, including a local judge and a state senate candidate.[4]

By the mid-1870s, Knight had separated from his wife, Serena, and had married Rachel, a former slave of his grandfather.[3] During the same period, Knight's son, Mat, married Rachel's daughter, Fannie, and Knight's daughter, Molly, married Rachel's son, Jeff.[1]:2 Newton and Rachel Knight had several children before her death in 1889.[3] Newton Knight died on February 16, 1922. In spite of a Mississippi law that barred the interment of whites and blacks in the same cemetery,[15] he was buried next to Rachel on a hill overlooking their farm.[3] Newton's engraved epitaph stated "He lived for others."[16]

Legacy

In 1935, Knight's son, Thomas Jefferson "Tom" Knight, published a book about his father, The Life and Activities of Captain Newton Knight. Tom Knight portrayed his father as a Civil War-era Robin Hood who refused to fight for a cause with which he did not agree. The book noticeably omits Newton Knight's post-war marriage to Rachel.[1]:2

The 1942 James H. Street novel, Tap Roots, is loosely based on the Knight Company's actions. Though the book is a work of fiction, the novel's protagonist, Hoab Dabney, was inspired by Newton Knight.[1]:2 The book was the basis of the 1948 film, Tap Roots, which was directed by George Marshall, and starred Van Heflin and Susan Hayward.

In the late 1940s, Davis Knight, a great-grandson of Newton and Rachel Knight, was charged with miscegeny for marrying a white woman. Much of the trial focused on the background of Rachel, namely whether or not she was actually black. Davis Knight was found guilty, but the verdict was eventually overturned by the Mississippi Supreme Court.[1]:1–3

In 1951, Knight's grandniece, Ethel Knight, published The Echo of the Black Horn, a scathing denunciation of Knight and the Knight Company. Dedicating the book to the Confederate veterans of Jones County, Ethel Knight portrayed Newton as a backward, ignorant, murderous traitor. She argued that most members of the Knight Company were not Unionists, but had been manipulated by Knight into joining his cause.[4]

During the latter half of the 20th century, much of the debate over the Knight Company shifted to whether or not Jones County was truly a pro-Union stronghold. In his 1984 book, The Legend of the Free State of Jones, Rudy Leverett argued that the Knight Company's actions were not representative of Jones County, and provided evidence that a majority of Jones Countians were loyal to the Confederacy.

In 2003, historian Victoria Bynum's book The Free State of Jones was published by the University of North Carolina Press. This book provides a broader view of the Knight Company, taking into account the economic, religious and genealogical factors that helped shape the views of Civil War-era residents of the Jones County area. Bynum provides numerous examples of Knight stating his pro-Union sentiments after the war, and notes the influence of the staunchly pro-Union Collins family, many of whom were members of the Knight Company. She also brings to light the many women and slaves who provided assistance to Knight and his men.

In 2009, Sally Jenkins and John Stauffer published The State of Jones, which elaborates on Knight's pro-Union sympathies and presents evidence that his views on race played a significant role in his actions during and after the war.

A biopic of Knight entitled The Free State of Jones, starring Matthew McConaughey and Gugu Mbatha-Raw, is in production and scheduled for release on March 11, 2016.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 1.8 1.9 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 1.16 Victoria Bynum, The Free State of Jones: Mississippi's Longest Civil War (University of North Carolina Press, 2003).

- ↑ Newton Knight at Find a Grave

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 3.8 3.9 3.10 3.11 3.12 James R. Kelly, Jr., "Newton Knight and the Legend of the Free State of Jones," Mississippi History Now, April 2009. Retrieved: 2 June 2013.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 4.7 4.8 Victoria Bynum, "Telling and Retelling the Legend of the 'Free State of Jones,'" Guerillas, Unionists, and Violence on the Confederate Home Front (University of Arkansas Press, 1999), pp. 17–29.

- ↑ Jenkins and Stauffer, State of Jones, p. 378

- ↑ Jenkins and Stauffer, State of Jones, p. 43-45

- ↑ Jenkins and Stauffer, State of Jones, p. 73-7

- ↑ Jenkins and Stauffer, State of Jones,p. 38-39, 80-82

- ↑ Jenkins and Stauffer, State of Jones, p. 82-83

- ↑ Jenkins and Stauffer, State of Jones, p. 95-99, 112-15

- ↑ Jenkins and Stauffer, State of Jones, p. 2-3, 137-41

- ↑ Official Records of the War, 1:32, part 3, pp. 662-63

- ↑ Sally Jenkins, John Stauffer, The State of Jones (2009) p. 5

- ↑ Samuel Willard, "A Myth of the Confederacy," The Nation, Vol. 54, No. 1395 (March 1892), p. 227.

- ↑ Jenkins and Stauffer, State of Jones, p. 283

- ↑ Jenkins and Stauffer, State of Jones, p. 307

Further reading

- Bynum, Victoria E. (2003), The Free State of Jones: Mississippi's Longest Civil War, Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, ISBN 0-8078-5467-0

- Jenkins, Sally; Stauffer, John (2009), The State of Jones, New York: Doubleday, ISBN 978-0-385-52593-0

- Knight, Ethel (1951), Echo of the Black Horn: An authentic tale of "the Governor" of "The Free State of Jones

|