Newton's theorem of revolving orbits

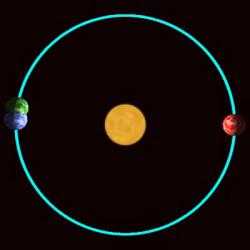

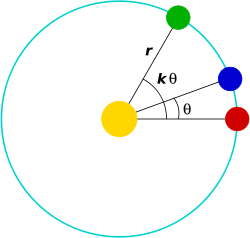

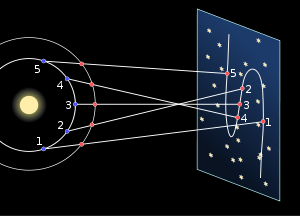

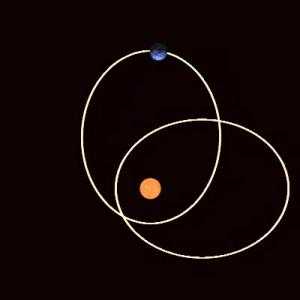

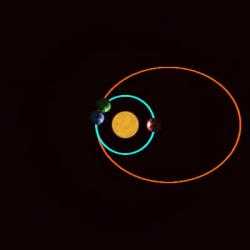

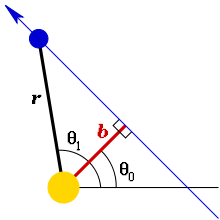

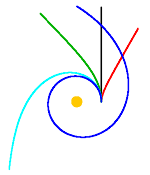

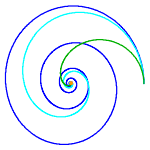

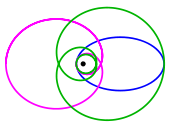

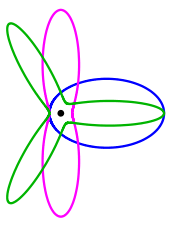

In classical mechanics, Newton's theorem of revolving orbits identifies the type of central force needed to multiply the angular speed of a particle by a factor k without affecting its radial motion (Figures 1 and 2). Newton applied his theorem to understanding the overall rotation of orbits (apsidal precession, Figure 3) that is observed for the Moon and planets. The term "radial motion" signifies the motion towards or away from the center of force, whereas the angular motion is perpendicular to the radial motion.

Isaac Newton derived this theorem in Propositions 43–45 of Book I of his Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica, first published in 1687. In Proposition 43, he showed that the added force must be a central force, one whose magnitude depends only upon the distance r between the particle and a point fixed in space (the center). In Proposition 44, he derived a formula for the force, showing that it was an inverse-cube force, one that varies as the inverse cube of r. In Proposition 45 Newton extended his theorem to arbitrary central forces by assuming that the particle moved in nearly circular orbit.

As noted by astrophysicist Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar in his 1995 commentary on Newton's Principia, this theorem remained largely unknown and undeveloped for over three centuries.[1] Since 1997, the theorem has been studied by Donald Lynden-Bell and collaborators.[2][3] Its first exact extension came in 2000 with the work of Mahomed and Vawda.[4]

Historical context

The motion of astronomical bodies has been studied systematically for thousands of years. The stars were observed to rotate uniformly, always maintaining the same relative positions to one another. However, other bodies were observed to wander against the background of the fixed stars; most such bodies were called planets after the Greek word "πλανήτοι" (planētoi) for "wanderers". Although they generally move in the same direction along a path across the sky (the ecliptic), individual planets sometimes reverse their direction briefly, exhibiting retrograde motion.

To describe this forward-and-backward motion, Apollonius of Perga (c. 262 – c. 190 BC) developed the concept of deferents and epicycles, according to which the planets are carried on rotating circles that are themselves carried on other rotating circles, and so on. Any orbit can be described with a sufficient number of judiciously chosen epicycles, since this approach corresponds to a modern Fourier transform.[5] Roughly 350 years later, Claudius Ptolemaeus published his Almagest, in which he developed this system to match the best astronomical observations of his era. To explain the epicycles, Ptolemy adopted the geocentric cosmology of Aristotle, according to which planets were confined to concentric rotating spheres. This model of the universe was authoritative for nearly 1500 years.

The modern understanding of planetary motion arose from the combined efforts of astronomer Tycho Brahe and physicist Johannes Kepler in the 16th century. Tycho is credited with extremely accurate measurements of planetary motions, from which Kepler was able to derive his laws of planetary motion. According to these laws, planets move on ellipses (not epicycles) about the Sun (not the Earth). Kepler's second and third laws make specific quantitative predictions: planets sweep out equal areas in equal time, and the square of their orbital periods equals a fixed constant times the cube of their semi-major axis. Subsequent observations of the planetary orbits showed that the long axis of the ellipse (the so-called line of apsides) rotates gradually with time; this rotation is known as apsidal precession. The apses of an orbit are the points at which the orbiting body is closest or furthest away from the attracting center; for planets orbiting the Sun, the apses correspond to the perihelion (closest) and aphelion (furthest).

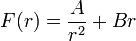

With the publication of his Principia roughly eighty years later (1687), Isaac Newton provided a physical theory that accounted for all three of Kepler's laws, a theory based on Newton's laws of motion and his law of universal gravitation. In particular, Newton proposed that the gravitational force between any two bodies was a central force F(r) that varied as the inverse square of the distance r between them. Arguing from his laws of motion, Newton showed that the orbit of any particle acted upon by one such force is always a conic section, specifically an ellipse if it does not go to infinity. However, this conclusion holds only when two bodies are present (the two-body problem); the motion of three bodies or more acting under their mutual gravitation (the n-body problem) remained unsolved for centuries after Newton,[6][7] although solutions to a few special cases were discovered.[8] Newton proposed that the orbits of planets about the Sun are largely elliptical because the Sun's gravitation is dominant; to first approximation, the presence of the other planets can be ignored. By analogy, the elliptical orbit of the Moon about the Earth was dominated by the Earth's gravity; to first approximation, the Sun's gravity and those of other bodies of the Solar System can be neglected. However, Newton stated that the gradual apsidal precession of the planetary and lunar orbits was due to the effects of these neglected interactions; in particular, he stated that the precession of the Moon's orbit was due to the perturbing effects of gravitational interactions with the Sun.

Newton's theorem of revolving orbits was his first attempt to understand apsidal precession quantitatively. According to this theorem, the addition of a particular type of central force—the inverse-cube force—can produce a rotating orbit; the angular speed is multiplied by a factor k, whereas the radial motion is left unchanged. However, this theorem is restricted to a specific type of force that may not be relevant; several perturbing inverse-square interactions (such as those of other planets) seem unlikely to sum exactly to an inverse-cube force. To make his theorem applicable to other types of forces, Newton found the best approximation of an arbitrary central force F(r) to an inverse-cube potential in the limit of nearly circular orbits, that is, elliptical orbits of low eccentricity, as is indeed true for most orbits in the Solar System. To find this approximation, Newton developed an infinite series that can be viewed as the forerunner of the Taylor expansion.[9] This approximation allowed Newton to estimate the rate of precession for arbitrary central forces. Newton applied this approximation to test models of the force causing the apsidal precession of the Moon's orbit. However, the problem of the Moon's motion is dauntingly complex, and Newton never published an accurate gravitational model of the Moon's apsidal precession. After a more accurate model by Clairaut in 1747,[10] analytical models of the Moon's motion were developed in the late 19th century by Hill,[11] Brown,[12] and Delaunay.[13]

However, Newton's theorem is more general than merely explaining apsidal precession. It describes the effects of adding an inverse-cube force to any central force F(r), not only to inverse-square forces such as Newton's law of universal gravitation and Coulomb's law. Newton's theorem simplifies orbital problems in classical mechanics by eliminating inverse-cube forces from consideration. The radial and angular motions, r(t) and θ1(t), can be calculated without the inverse-cube force; afterwards, its effect can be calculated by multiplying the angular speed of the particle

Mathematical statement

Consider a particle moving under an arbitrary central force F1(r) whose magnitude depends only on the distance r between the particle and a fixed center. Since the motion of a particle under a central force always lies in a plane, the position of the particle can be described by polar coordinates (r, θ1), the radius and angle of the particle relative to the center of force (Figure 1). Both of these coordinates, r(t) and θ1(t), change with time t as the particle moves.

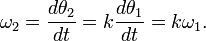

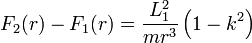

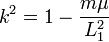

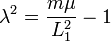

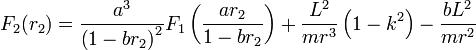

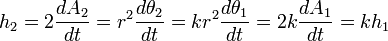

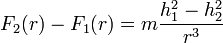

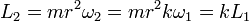

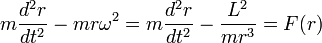

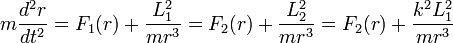

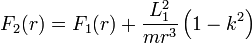

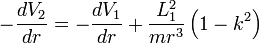

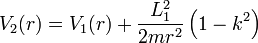

Imagine a second particle with the same mass m and with the same radial motion r(t), but one whose angular speed is k times faster than that of the first particle. In other words, the azimuthal angles of the two particles are related by the equation θ2(t) = k θ1(t). Newton showed that the motion of the second particle can be produced by adding an inverse-cube central force to whatever force F1(r) acts on the first particle[14]

where L1 is the magnitude of the first particle's angular momentum, which is a constant of motion (conserved) for central forces.

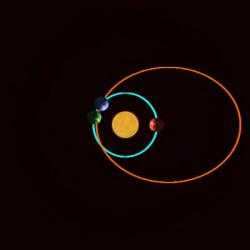

If k2 is greater than one, F2 − F1 is a negative number; thus, the added inverse-cube force is attractive, as observed in the green planet of Figures 1–4 and 9. By contrast, if k2 is less than one, F2−F1 is a positive number; the added inverse-cube force is repulsive, as observed in the green planet of Figures 5 and 10, and in the red planet of Figures 4 and 5.

Alteration of the particle path

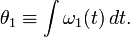

The addition of such an inverse-cube force also changes the path followed by the particle. The path of the particle ignores the time dependencies of the radial and angular motions, such as r(t) and θ1(t); rather, it relates the radius and angle variables to one another. For this purpose, the angle variable is unrestricted and can increase indefinitely as the particle revolves around the central point multiple times. For example, if the particle revolves twice about the central point and returns to its starting position, its final angle is not the same as its initial angle; rather, it has increased by 2×360° = 720°. Formally, the angle variable is defined as the integral of the angular speed

A similar definition holds for θ2, the angle of the second particle.

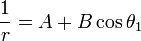

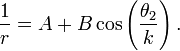

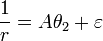

If the path of the first particle is described in the form r = g(θ1), the path of the second particle is given by the function r = g(θ2/k), since θ2 = k θ1. For example, let the path of the first particle be an ellipse

where A and B are constants; then, the path of the second particle is given by

Orbital precession

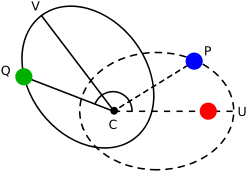

If k is close, but not equal, to one, the second orbit resembles the first, but revolves gradually about the center of force; this is known as orbital precession (Figure 3). If k is greater than one, the orbit precesses in the same direction as the orbit (Figure 3); if k is less than one, the orbit precesses in the opposite direction.

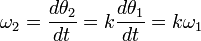

Although the orbit in Figure 3 may seem to rotate uniformly, i.e., at a constant angular speed, this is true only for circular orbits.[2][3] If the orbit rotates at an angular speed Ω, the angular speed of the second particle is faster or slower than that of the first particle by Ω; in other words, the angular speeds would satisfy the equation ω2 = ω1 + Ω. However, Newton's theorem of revolving orbits states that the angular speeds are related by multiplication: ω2 = kω1, where k is a constant. Combining these two equations shows that the angular speed of the precession equals Ω = (k − 1)ω1. Hence, Ω is constant only if ω1 is constant. According to the conservation of angular momentum, ω1 changes with the radius r

where m and L1 are the first particle's mass and angular momentum, respectively, both of which are constant. Hence, ω1 is constant only if the radius r is constant, i.e., when the orbit is a circle. However, in that case, the orbit does not change as it precesses.

Illustrative example: Cotes's spirals

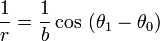

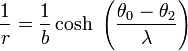

The simplest illustration of Newton's theorem occurs when there is no initial force, i.e., F1(r) = 0. In this case, the first particle is stationary or travels in a straight line. If it travels in a straight line that does not pass through the origin (blue line in Figure 6) the equation for such a line may be written in the polar coordinates (r, θ1) as

where θ0 is the angle at which the distance is minimized (Figure 6). The distance r begins at infinity (when θ1 – θ0 = −90°), and decreases gradually until θ1 – θ0 = 0°, when the distance reaches a minimum, then gradually increases again to infinity at θ1 – θ0 = 90°. The minimum distance b is the impact parameter, which is defined as the length of the perpendicular from the fixed center to the line of motion. The same radial motion is possible when an inverse-cube central force is added.

An inverse-cube central force F2(r) has the form

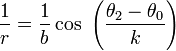

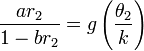

where the numerator μ may be positive (repulsive) or negative (attractive). If such an inverse-cube force is introduced, Newton's theorem says that the corresponding solutions have a shape called Cotes's spirals. These are curves defined by the equation

where the constant k equals

When the right-hand side of the equation is a positive real number, the solution corresponds to an epispiral. When the argument θ1 – θ0 equals ±90°×k, the cosine goes to zero and the radius goes to infinity. Thus, when k is less than one, the range of allowed angles becomes small and the force is repulsive (red curve on right in Figure 7). On the other hand, when k is greater than one, the range of allowed angles increases, corresponding to an attractive force (green, cyan and blue curves on left in Figure 7); the orbit of the particle can even wrap around the center several times. The possible values of the parameter k may range from zero to infinity, which corresponds to values of μ ranging from negative infinity up to the positive upper limit, L12/m. Thus, for all attractive inverse-cube forces (negative μ) there is a corresponding epispiral orbit, as for some repulsive ones (μ < L12/m), as illustrated in Figure 7. Stronger repulsive forces correspond to a faster linear motion.

One of the other solution types is given in terms of the hyperbolic cosine:

where the constant λ satisfies

This form of Cotes's spirals corresponds to one of the two Poinsot's spirals (Figure 8). The possible values of λ range from zero to infinity, which corresponds to values of μ greater than the positive number L12/m. Thus, Poinsot spiral motion only occurs for repulsive inverse-cube central forces, and applies in the case that L is not too large for the given μ.

Taking the limit of k or λ going to zero yields the third form of a Cotes's spiral, the so-called reciprocal spiral or hyperbolic spiral, as a solution

where A and ε are arbitrary constants. Such curves result when the strength μ of the repulsive force exactly balances the angular momentum-mass term

Closed orbits and inverse-cube central forces

Two types of central forces—those that increase linearly with distance, F = Cr, such as Hooke's law, and inverse-square forces, F = C/r2, such as Newton's law of universal gravitation and Coulomb's law—have a very unusual property. A particle moving under either type of force always returns to its starting place with its initial velocity, provided that it lacks sufficient energy to move out to infinity. In other words, the path of a bound particle is always closed and its motion repeats indefinitely, no matter what its initial position or velocity. As shown by Bertrand's theorem, this property is not true for other types of forces; in general, a particle will not return to its starting point with the same velocity.

However, Newton's theorem shows that an inverse-cubic force may be applied to a particle moving under a linear or inverse-square force such that its orbit remains closed, provided that k equals a rational number. (A number is called "rational" if it can be written as a fraction m/n, where m and n are integers.) In such cases, the addition of the inverse-cubic force causes the particle to complete m rotations about the center of force in the same time that the original particle completes n rotations. This method for producing closed orbits does not violate Bertrand's theorem, because the added inverse-cubic force depends on the initial velocity of the particle.

Harmonic and subharmonic orbits are special types of such closed orbits. A closed trajectory is called a harmonic orbit if k is an integer, i.e., if n = 1 in the formula k = m/n. For example, if k = 3 (green planet in Figures 1 and 4, green orbit in Figure 9), the resulting orbit is the third harmonic of the original orbit. Conversely, the closed trajectory is called a subharmonic orbit if k is the inverse of an integer, i.e., if m = 1 in the formula k = m/n. For example, if k = 1/3 (green planet in Figure 5, green orbit in Figure 10), the resulting orbit is called the third subharmonic of the original orbit. Although such orbits are unlikely to occur in nature, they are helpful for illustrating Newton's theorem.[2]

Limit of nearly circular orbits

In Proposition 45 of his Principia, Newton applies his theorem of revolving orbits to develop a method for finding the force laws that govern the motions of planets. Johannes Kepler had noted that the orbits of most planets and the Moon seemed to be ellipses, and the long axis of those ellipses can determined accurately from astronomical measurements. The long axis is defined as the line connecting the positions of minimum and maximum distances to the central point, i.e., the line connecting the two apses. For illustration, the long axis of the planet Mercury is defined as the line through its successive positions of perihelion and aphelion. Over time, the long axis of most orbiting bodies rotates gradually, generally no more than a few degrees per complete revolution, because of gravitational perturbations from other bodies, oblateness in the attracting body, general relativistic effects, and other effects. Newton's method uses this apsidal precession as a sensitive probe of the type of force being applied to the planets.

Newton's theorem describes only the effects of adding an inverse-cube central force. However, Newton extends his theorem to an arbitrary central forces F(r) by restricting his attention to orbits that are nearly circular, such as ellipses with low orbital eccentricity (ε ≤ 0.1), which is true of seven of the eight planetary orbits in the solar system. Newton also applied his theorem to the planet Mercury,[15] which has an eccentricity ε of roughly 0.21, and suggested that it may pertain to Halley's comet, whose orbit has an eccentricity of roughly 0.97.[16]

A qualitative justification for this extrapolation of his method has been suggested by Valluri, Wilson and Harper.[16] According to their argument, Newton considered the apsidal precession angle α (the angle between the vectors of successive minimum and maximum distance from the center) to be a smooth, continuous function of the orbital eccentricity ε. For the inverse-square force, α equals 180°; the vectors to the positions of minimum and maximum distances lie on the same line. If α is initially not 180° at low ε (quasi-circular orbits) then, in general, α will equal 180° only for isolated values of ε; a randomly chosen value of ε would be very unlikely to give α = 180°. Therefore, the observed slow rotation of the apsides of planetary orbits suggest that the force of gravity is an inverse-square law.

Quantitative formula

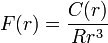

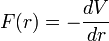

To simplify the equations, Newton writes F(r) in terms of a new function C(r)

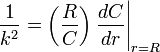

where R is the average radius of the nearly circular orbit. Newton expands C(r) in a series—now known as a Taylor expansion—in powers of the distance r, one of the first appearances of such a series.[17] By equating the resulting inverse-cube force term with the inverse-cube force for revolving orbits, Newton derives an equivalent angular scaling factor k for nearly circular orbits[18]

In other words, the application of an arbitrary central force F(r) to a nearly circular elliptical orbit can accelerate the angular motion by the factor k without affecting the radial motion significantly. If an elliptical orbit is stationary, the particle rotates about the center of force by 180° as it moves from one end of the long axis to the other (the two apses). Thus, the corresponding apsidal angle α for a general central force equals k×180°, using the general law θ2 = k θ1.

Examples

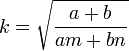

Newton illustrates his formula with three examples. In the first two, the central force is a power law, F(r) = rn−3 and, hence,C(r) is proportional to rn. The formula above indicates that the angular motion is multiplied by a factor k = 1/√n, so that the apsidal angle α equals 180°/√n.

This angular scaling can be seen in the apsidal precession, i.e., in the gradual rotation of the long axis of the ellipse (Figure 3). As noted above, the orbit as a whole rotates with a mean angular speed Ω=(k−1)ω, where ω equals the mean angular speed of the particle about the stationary ellipse. If the particle requires a time T to move from one apse to the other, this implies that, in the same time, the long axis will rotate by an angle β = ΩT = (k − 1)ωT = (k − 1)×180°. For an inverse-square law such as Newton's law of universal gravitation, where n equals 1, there is no angular scaling (k = 1), the apsidal angle α is 180°, and the elliptical orbit is stationary (Ω = β = 0).

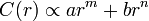

As a final illustration, Newton considers a sum of two power laws

which multiplies the angular speed by a factor

Newton applies both of these formulae (the power law and sum of two power laws) to examine the apsidal precession of the Moon's orbit.

Precession of the Moon's orbit

The motion of the Moon can be measured accurately, and is noticeably more complex than that of the planets.[19] The ancient Greek astronomers, Hipparchus and Ptolemy, had noted several periodic variations in the Moon's orbit,[19] such as small oscillations in its orbital eccentricity and the inclination of its orbit to the plane of the ecliptic. These oscillations generally occur on a once-monthly or twice-monthly time-scale. The line of its apses precesses gradually with a period of roughly 8.85 years, while its line of nodes turns a full circle in roughly double that time, 18.6 years.[20] This accounts for the roughly 18-year periodicity of eclipses, the so-called Saros cycle. However, both lines experience small fluctuations in their motion, again on the monthly time-scale.

In 1673, Jeremiah Horrocks published a reasonably accurate model of the Moon's motion in which the Moon was assumed to follow a precessing elliptical orbit.[21][22] An sufficiently accurate and simple method for predicting the Moon's motion would have solved the navigational problem of determining a ship's longitude;[23] in Newton's time, the goal was to predict the Moon's position to 2' (two arc-minutes), which would correspond to a 1° error in terrestrial longitude.[24] Horrocks' model predicted the lunar position with errors no more than 10 arc-minutes;[24] for comparison, the diameter of the Moon is roughly 30 arc-minutes.

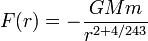

Newton used his theorem of revolving orbits in two ways to account for the apsidal precession of the Moon.[25] First, he showed that the Moon's observed apsidal precession could be accounted for by changing the force law of gravity from an inverse-square law to a power law in which the exponent was 2 + 4/243 (roughly 2.0165)[26]

In 1894, Asaph Hall adopted this approach of modifying the exponent in the inverse-square law slightly to explain an anomalous orbital precession of the planet Mercury,[27] which had been observed in 1859 by Urbain Le Verrier.[28] Ironically, Hall's theory was ruled out by careful astronomical observations of the Moon.[29] The currently accepted explanation for this precession involves the theory of general relativity, which (to first approximation) adds an inverse-quartic force, i.e., one that varies as the inverse fourth power of distance.[30]

As a second approach to explaining the Moon's precession, Newton suggested that the perturbing influence of the Sun on the Moon's motion might be approximately equivalent to an additional linear force

The first term corresponds to the gravitational attraction between the Moon and the Earth, where r is the Moon's distance from the Earth. The second term, so Newton reasoned, might represent the average perturbing force of the Sun's gravity of the Earth-Moon system. Such a force law could also result if the Earth were surrounded by a spherical dust cloud of uniform density.[31] Using the formula for k for nearly circular orbits, and estimates of A and B, Newton showed that this force law could not account for the Moon's precession, since the predicted apsidal angle α was (≈ 180.76°) rather than the observed α (≈ 181.525°). For every revolution, the long axis would rotate 1.5°, roughly half of the observed 3.0°[25]

Generalization

Isaac Newton first published his theorem in 1687, as Propositions 43–45 of Book I of his Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica. However, as astrophysicist Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar noted in his 1995 commentary on Newton's Principia, the theorem remained largely unknown and undeveloped for over three centuries.[1]

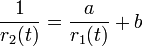

The first generalization of Newton's theorem was discovered by Mahomed and Vawda in 2000.[4] As Newton did, they assumed that the angular motion of the second particle was k times faster than that of the first particle, θ2 = k θ1. In contrast to Newton, however, Mahomed and Vawda did not require that the radial motion of the two particles be the same, r1 = r2. Rather, they required that the inverse radii be related by a linear equation

This transformation of the variables changes the path of the particle. If the path of the first particle is written r1 = g(θ1), the second particle's path can be written as

If the motion of the first particle is produced by a central force F1(r), Mahomed and Vawda showed that the motion of the second particle can be produced by the following force

According to this equation, the second force F2(r) is obtained by scaling the first force and changing its argument, as well as by adding inverse-square and inverse-cube central forces.

For comparison, Newton's theorem of revolving orbits corresponds to the case a = 1 and b = 0, so that r1 = r2. In this case, the original force is not scaled, and its argument is unchanged; the inverse-cube force is added, but the inverse-square term is not. Also, the path of the second particle is r2 = g(θ2/k), consistent with the formula given above.

Derivations

Newton's derivation

Newton's derivation is found in Section IX of his Principia, specifically Propositions 43–45.[32] His derivations of these Propositions are based largely on geometry.

- Proposition 43; Problem 30

- It is required to make a body move in a curve that revolves about the center of force in the same manner as another body in the same curve at rest.[33]

Newton's derivation of Proposition 43 depends on his Proposition 2, derived earlier in the Principia.[34] Proposition 2 provides a geometrical test for whether the net force acting on a point mass (a particle) is a central force. Newton showed that a force is central if and only if the particle sweeps out equal areas in equal times as measured from the center.

Newton's derivation begins with a particle moving under an arbitrary central force F1(r); the motion of this particle under this force is described by its radius r(t) from the center as a function of time, and also its angle θ1(t). In an infinitesimal time dt, the particle sweeps out an approximate right triangle whose area is

Since the force acting on the particle is assumed to be a central force, the particle sweeps out equal angles in equal times, by Newton's Proposition 2. Expressed another way, the rate of sweeping out area is constant

This constant areal velocity can be calculated as follows. At the apapsis and periapsis, the positions of closest and furthest distance from the attracting center, the velocity and radius vectors are perpendicular; therefore, the angular momentum L1 per mass m of the particle (written as h1) can be related to the rate of sweeping out areas

Now consider a second particle whose orbit is identical in its radius, but whose angular variation is multiplied by a constant factor k

The areal velocity of the second particle equals that of the first particle multiplied by the same factor k

Since k is a constant, the second particle also sweeps out equal areas in equal times. Therefore, by Proposition 2, the second particle is also acted upon by a central force F2(r). This is the conclusion of Proposition 43.

- Proposition 44

- The difference of the forces, by which two bodies may be made to move equally, one in a fixed, the other in the same orbit revolving, varies inversely as the cube of their common altitudes.[35]

To find the magnitude of F2(r) from the original central force F1(r), Newton calculated their difference F2(r) − F1(r) using geometry and the definition of centripetal acceleration. In Proposition 44 of his Principia, he showed that the difference is proportional to the inverse cube of the radius, specifically by the formula given above, which Newtons writes in terms of the two constant areal velocities, h1 and h2

- Proposition 45; Problem 31

- To find the motion of the apsides in orbits approaching very near to circles.[36]

In this Proposition, Newton derives the consequences of his theorem of revolving orbits in the limit of nearly circular orbits. This approximation is generally valid for planetary orbits and the orbit of the Moon about the Earth. This approximation also allows Newton to consider a great variety of central force laws, not merely inverse-square and inverse-cube force laws.

Modern derivation

Modern derivations of Newton's theorem have been published by Whittaker (1937)[37] and Chandrasekhar (1995).[33] By assumption, the second angular speed is k times faster than the first

Since the two radii have the same behavior with time, r(t), the conserved angular momenta are related by the same factor k

The equation of motion for a radius r of a particle of mass m moving in a central potential V(r) is given by Lagrange's equations

Applying the general formula to the two orbits yields the equation

which can be re-arranged to the form

This equation relating the two radial forces can be understood qualitatively as follows. The difference in angular speeds (or equivalently, in angular momenta) causes a difference in the centripetal force requirement; to offset this, the radial force must be altered with an inverse-cube force.

Newton's theorem can be expressed equivalently in terms of potential energy, which is defined for central forces

The radial force equation can be written in terms of the two potential energies

Integrating with respect to the distance r, Newtons's theorem states that a k-fold change in angular speed results from adding an inverse-square potential energy to any given potential energy V1(r)

See also

- Kepler problem

- Laplace–Runge–Lenz vector

- Bertrand's theorem

- Two-body problem in general relativity

- Newton's theorem about ovals

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Chandrasekhar, p. 183.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Lynden-Bell, D; Lynden-Bell RM (1997). "On the Shapes of Newton's Revolving Orbits". Notes and Records of the Royal Society of London 51 (2): 195–198. doi:10.1098/rsnr.1997.0016.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Lynden-Bell D, Jin S (2008). "Analytic central orbits and their transformation group". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 386 (1): 245–260. arXiv:0711.3491. Bibcode:2008MNRAS.386..245L. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2008.13018.x.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Mahomed FM, Vawda F (2000). "Application of Symmetries to Central Force Problems". Nonlinear Dynamics 21 (4): 307–315. doi:10.1023/A:1008317327402.

- ↑ Sugon QM, Bragais S, McNamara DJ (2008) Copernicus’s epicycles from Newton’s gravitational force law via linear perturbation theory in geometric algebra.

- ↑ Whittaker, pp. 339–385.

- ↑ Sundman KF (1912). "Memoire sur le probleme de trois corps". Acta Mathematica 36 (1): 105–179. doi:10.1007/BF02422379.

- ↑ Hiltebeitel AM (1911). "On the Problem of Two Fixed Centres and Certain of its Generalizations". American Journal of Mathematics (The Johns Hopkins University Press) 33 (1/4): 337–362. doi:10.2307/2369997. JSTOR 2369997.

- ↑ Cohen, p. 147.

- ↑ Clairaut, AC (1745). "Du Système du Monde dans les principes de la gravitation universelle". Histoire de l'Académie royale des sciences avec les mémoires de mathématique et de physique 1749: 329–364.

- ↑ Hill GW (1894). "Literal expression for the motion of the moon's perigee". Ann. Math. 9: 31. doi:10.2307/1967502. JSTOR 1967502.

- ↑ Brown EW (1891). "Unknown title". Am. J. Math. (The Johns Hopkins University Press) 13 (2): 159–172. doi:10.2307/2369812. JSTOR 2369812.

Brown EW (1891). "Unknown title". Monthly Notices Roy. Astron. Soc. 52: 71. - ↑ Delaunay C (1862). "Unknown title". Mémoires Acad. Imp. Sc.: 237.

Delaunay C (1867). "Unknown title". Mémoires Acad. Imp. Sc.: 451. - ↑ Newton, Principia, section IX of Book I, Propositions 43–45, pp. 135–147.

- ↑ Newton, Principia, Book III, Proposition 2, p. 406.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Valluri S. R.; Wilson C.; Harper W. (1997). "Newton's Apsidal Precession Theorem and Eccentric Orbits". Journal of the History of Astronomy 28: 13–27. Bibcode:1997JHA....28...13V.

- ↑ Cohen IB (1990). "Halley's Two Essays on Newton's Principia". In Norman Thrower, editor. Standing on the Shoulders of Giants: A Longer View of Newton and Halley. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. pp. 91–108. ISBN 978-0-520-06589-5.

- ↑ Chandrasekhar, pp. 193–194.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Cook A (2000). "Success and Failure in Newton's Lunar Theory". Astronomy and Geophysics 41 (6): 21–25. Bibcode:2000A&G....41f..21C. doi:10.1046/j.1468-4004.2000.41621.x.

- ↑ Smith, p. 252.

- ↑ Horrocks J (1673). Jeremia Horocii opera posthuma. London: G Godbit for J Martyn.

- ↑ Wilson C (1987). "On the Origin of Horrock's Lunar Theory". Journal for the History of Astronomy 18: 77–94. Bibcode:1987JHA....18...77W.

- ↑ Kollerstrom N (2000). Newton's Forgotten Lunar Theory: His Contribution to the Quest for Longitude. Green Lion Press. ISBN 978-1-888009-08-8.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Smith, p. 254.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Newton, Principia, Book I, Section IX, Proposition 45, pp. 141–147.

- ↑ Chandrasekhar, p. 198.

- ↑ Hall A (1894). "A suggestion in the theory of Mercury". The Astronomical Journal 14: 49–51. Bibcode:1894AJ.....14...49H. doi:10.1086/102055.

- ↑ Le Verrier UJJ (1859). "Théorie du mouvement de Mercure". Annales de l'Observatoire Impérial de Paris 5: 1–196, esp. 98–106. Bibcode:1859AnPar...5....1L.

Simon Newcomb (1882). "Discussion and Results of Observations on Transits of Mercury from 1677 to 1881". Astronomical Papers Prepared for the Use of the American Ephemeris and Nautical Almanac 1: 473. Bibcode:1882USNAO...1..363N. - ↑ Brown EW (1903). "On the degree of accuracy in the new lunary theory". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 64: 524–534.

- ↑ Roseveare N (1982). Mercury's perihelion from Le verrier to Einstein. Oxford.

- ↑ Symon KR (1971). Mechanics (3rd ed.). Reading, MA: Addison–Wesley. pp. 267 (Chapter 6, problem 7). ISBN 0-201-07392-7.

- ↑ Chandrasekhar, pp. 183–192.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 Chandrasekhar, p. 184.

- ↑ Chandrasekhar, pp. 67–70.

- ↑ Chandrasekhar, p. 187.

- ↑ Chandrasekhar, p. 192.

- ↑ Whittaker, p. 83.

Bibliography

- Newton I (1999). The Principia: Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy (3rd edition (1726); translated by I. Bernard Cohen and Anne Whitman, assisted by Julia Budenz ed.). Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. pp. 147–148, 246–264, 534–545. ISBN 978-0-520-08816-0.

- Chandrasekhar S (1995). Newton’s Principia for the Common Reader. Oxford University Press. pp. 183–200. ISBN 978-0-19-852675-9.

- Pars, L.A. (1965). A Treatise on Analytical Dynamics. John Wiley and Sons. p. 56. ISBN 978-0-918024-07-7. LCCN 64024556.

- Whittaker ET (1937). A Treatise on the Analytical Dynamics of Particles and Rigid Bodies, with an Introduction to the Problem of Three Bodies (4th ed.). New York: Dover Publications. p. 83. ISBN 978-0-521-35883-5.

- Routh EJ (1960). A Treatise on Dynamics of a Particle (reprint of 1898 ed.). New York: Dover Publications. pp. 230–233 (sections §356–359). ISBN 978-0-548-96521-4.

- Rouse Ball WW (1893). An Essay on Newton’s "Principia". Macmillan and Co. (reprint, Merchant Books). pp. 84–85. ISBN 978-1-60386-012-3.

Further reading

- Bertrand J (1873). "Théorème relatif au mouvement d'un point attiré vers un centre fixe". Comptes rendus des séances de l'Academie des Sciences. xxvii/10: 849–853. (séance du lundi 20 Octobre 1873)

- Cohen IB (1999). "A Guide to Newton's Principia". The Principia: Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. pp. 147–148, 246–252. ISBN 978-0-520-08816-0.

- Cook A (1988). The Motion of the Moon. Bristol: Adam Hilger. ISBN 0-85274-348-3.

- D’Eliseo, MM (2007). "The first-order orbital equation". American Journal of Physics 75 (4): 352–355. Bibcode:2007AmJPh..75..352D. doi:10.1119/1.2432126.

- Guicciardini, Niccolò (1999). Reading the Principia: The Debate on Newton's Mathematical Methods for Natural Philosophy from 1687 to 1736. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-54403-0.

- Newton I (1966). Principia Vol. I The Motion of Bodies (based on Newton's 2nd edition (1713); translated by Andrew Motte (1729) and revised by Florian Cajori (1934) ed.). Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. pp. 135–147 (Section IX of Book I). ISBN 978-0-520-00928-8. Alternative translation of earlier (2nd) edition of Newton's Principia.

- Smith GE (1999). "Newton and the Problem of the Moon's Motion". The Principia: Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. pp. 252–257. ISBN 978-0-520-08816-0.

- Smith GE (1999). "Motion of the Lunar Apsis". The Principia: Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. pp. 257–264. ISBN 978-0-520-08816-0.

- Spivak, Michael (1994). "Planetary Motion". Calculus (3rd ed.). Publish or Perish. ISBN 0-914098-89-6.

External links

- Three-body problem discussed by Alain Chenciner at Scholarpedia