New states of Germany

The new federal states of Germany (German: die neuen Bundesländer) are the five re-established states in the former German Democratic Republic that acceded to the Federal Republic of Germany with its 10 states upon German reunification on 3 October 1990. Subsequently, the Gesellschaft für deutsche Sprache chose the term as German Word of the Year.[1]

The new states, which had been abolished by the East German government in 1952 and were re-established in 1990, are Brandenburg, Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, Saxony, Saxony-Anhalt and Thuringia. The state of Berlin, the result of a merger between East and West Berlin, is usually not considered one of the new states, although many of its residents are former East Germans.

Since the reunification, Germany thus consists of 16 states with equal legal statuses. Yet the process of the "inner reunification" between the former Eastern and Western Germany is still ongoing.

Culture

Persisting differences in culture and mentality among the old East Germany and old West Germany are often referred to as the "wall in the head" ("Mauer im Kopf").[2] "Ossis" ("Easties") are stereotyped as racist, poor and largely influenced by Russian culture.[3] "Wessis" ("Westies") are usually considered snobbish, dishonest, wealthy, and selfish. The terms can be considered disparaging.

In 2009, twenty years after the fall of the wall, a poll found that 22% of former East Germans (40% of under-25s) considered themselves "real citizens of the Federal Republic".[4] 62% feel in a kind of limbo, no longer citizens of East Germany but not fully integrated into the unified Germany. Around 11% would have liked to have East Germany back.[4] A 2004 poll found that 25% of West Germans and 12% of East Germans wished reunification had not happened.[2]

Some East German brands have been revived, appealing to former East Germans who are nostalgic for the goods they grew up with.[5] Brands revived in this manner include Rotkäppchen, which holds about 40% of the German sparkling wine market, and Zeha, the sport shoe maker that supplied most of East Germany's sports teams and also the Soviet national football team.[5]

Pornography and prostitution, considered by the government a sign of bourgeois decadence, were illegal in the GDR, and it is commonly believed that Germans who grew up during the communist years are more sexually inhibited than their western counterparts.[6] Nonetheless, better access to higher education and jobs along with free abortion, contraception and generous family policies made East German women generally more emancipated with respect to their sex life.[6]

More children are born out of wedlock in eastern Germany than in western Germany. In 2009, in eastern Germany 61% of births were to unmarried women, while in western Germany 27% were. The states of Saxony-Anhalt and Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania had the highest rate of birth outside wedlock, each with 64%, followed by Brandenburg with 62%. The state of Baden-Württemberg had the lowest rate with 22%, followed by Hesse and Bavaria, each with 26%.[7]

Economy

The economic reconstruction of eastern Germany (German: Aufbau Ost) is proving to be more long-term than originally foreseen.[8] The standard of living and annual income remains significantly lower in the new federal states.[9]

Reunification cost the federal government €2 Trillion.[10] At reunification, almost all East German industry was considered outdated.[8] The government privatised 8,500 state-owned East German enterprises.[10] Since 1990, between €100 billion and €140 billion a year have been transferred to the new states.[10] More than $60 billion were spent supporting businesses and building infrastructure in the years 2006-2008.[11]

A €156 billion economic plan, Solidarity Pact II, came into force in 2005, and provides the financial basis for the advancement and special promotion of economy of the new federal states until 2019.[8] The "solidarity tax", a 5.5% surcharge on the income tax, was instated by the Kohl government to restore the infrastructure of the new states to the levels of the western ones [12] and to apportion the cost of the unification as well as the expenses for the Gulf War and the European integration. The tax, which raises €11 billion a year, will be maintained until 2019 at least.[12]

Ever since the reunification, the unemployment rate in the east has been almost twice that of the west, currently at 12.7%[13] (as of April 2010) after having reached a maximum of 18.7% in 2005. In the 1999-2009 decade, economic activity per person has risen from 67% to 71% of western Germany.[11] According to Wolfgang Tiefensee in 2009, the minister then responsible for the development of the new federal states, “The gap is closing.”[11] Eastern Germany is also the part of the country least affected by the current financial crisis.[14]

All the new federal states, excluding Berlin, qualify as Objective 1 development regions within the European Union, and are eligible to receive investment subsidies of up to 30% until 2013.

Infrastructure

The "German Unity Transport Projects" (Verkehrsprojekte Deutsche Einheit) is a programme launched in 1991 and meant to upgrade the infrastructure of eastern Germany, and modernise transport links between the old and new federal states.[15]

The program consist of 9 rail and 7 motorway projects, as well as one waterway project, for a total funding of €38.5 billion. As of 2009, all 17 projects are either under construction or have already been completed.[16] The construction of new railway lines and high-speed upgrades of existing lines reduced journey times between Berlin and Hanover from over four hours to 96 minutes.[15] Due to increasing car usage and depopulation since reunification many railway lines (branches and main lines) have been closed by the unified Deutsche Bahn (German Railways).

"DEGES" (Deutsche Einheit Fernstraßenplanungs- und -bau GmbH, German Unity Road Construction Company) is the state-owned project management institution responsible for the construction of approximately 1,360 km of federal roads within the VDE, for a total investment of €10.2 billion. It is also involved in other transport projects, including a 435 km of roads for approximately € 1,760 million as well as a city tunnel in Leipzig, at the cost of €685 million.[17]

The Federal Transport Infrastructure Plan 2003 includes plans for the extension of the A14 from Magdeburg to Schwerin and construction of the A72 from Chemnitz to Leipzig.[16]

Private ownership rates of cars have markedly increased since 1990: in 1988, 55% of East German households had at least one car, in 1993 it had already risen to 67%, and to 71% in 1998. This compares to the West German rates of 61% for 1988, 74% for 1993 and 76% for 1998.[18][19]

Politics

The socialist party The Left (Die Linke, successor to the Party of Democratic Socialism, the GDR state party's successor) has been successful throughout eastern Germany, capitalising on the continued disparity of living conditions and salaries with western Germany, and high unemployment.[20]

Far right

After 1990, far right and Nationalist groups gained followers. Some sources claim mostly among people frustrated by the high unemployment and the poor economic situation.[21] Der Spiegel also points out that these people are mostly single men and that there may also be social-demographic reasons.[22]

The National Democratic Party of Germany (NPD) won 9.2% of the vote in 2004 state parliament elections in Saxony, and the party has eight seats in the state parliament in Dresden, just behind the 13 held by the Social Democrats. Far right parties also have seats in the parliaments of Brandenburg and in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern.[23]

In the Saxony state election of September 2009 the NPD lost votes (-3.6%) and seats (-4),[24] while in the same month the German People's Union lost its representation in the Landtag of Brandenburg.[25]

A survey of 14 to 25-year-olds carried out by the Forsa opinion poll institute found that one out of two youths in eastern Germany now believe that National Socialism had “its good sides”.[21]

In 2009, Junge Landsmannschaft Ostdeutschland, which is supported by the NPD, organized a march on the anniversary of the Bombing of Dresden in World War II. There were 6,000 Nationalists, met by tens of thousands of anti-Nazis and several thousand police.[26]

Demographic development

The former East German states have experienced significant depopulation and extremely low birth rates since 1990, with a recovery in recent years. About 1.7 million people have left the new federal states since the fall of the Berlin Wall, or 12% of the population.[11] A disproportionately high number of them were women under 35.[22] In fact about 500,000 women aged under 30 have left for western Germany in the past 15 years.[27]

After 1990, the fertility rate in the East dropped to 0.77. In 2006, the rates in the new states (1.30) was approaching those in the West (1.34), and is now higher (1.45 vs 1.37 in West, year 2012).[28][29] Since 1989, about 2,000 schools have closed because of a paucity of children.[11]

In some regions the number of women between the ages of 20 and 30 has dropped by more than 30 percent.[11] In 2004, in the age group 18-29 (statistically important for starting families) there were only 90 women for every 100 men in the new federal states (including Berlin).[28] In parts of the state of Thuringia, there are 82 women for every 100 men.[27] The town of Königstein has the biggest demographic imbalance in Europe between young men and women.[27] This is in contrast to many areas in Europe as many cities across the continent suffer an imbalance of younger women to men.[30] This has led to the concern to local leaders, as a large imbalance of males to females is usually linked to historical social instabilities and increased crime rates.[27]

Around 300,000 homes have been demolished in recent years. In parts of eastern Germany, wolves and lynx have reappeared after many decades.[27]

Demographic evolution

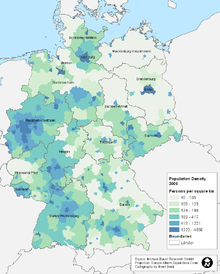

Brandenburg had a population of 2,660,000 in 1989, and 2,447,700 in March 2013.[31] It has the second lowest population density in Germany. In 1995, it became the only new state to experience population growth, aided by the vicinity of Berlin.[32]

Mecklenburg-Vorpommern had a population of 1,970,000 in 1989, and 1,598,000 in March 2013,[31] with the lowest population density in Germany. The local Landtag held several inquiries over population trends, the opposition has requested an annual report on the topic.[32]

Saxony had a population of 5,003,000 in 1989, which fell to 4,044,000 in March 2013.[31] It still remains the most populous among the five new states. The proportion of the population under 20 fell from 24.6% in 1988 to 19.7% in 1999.[32] Dresden and Leipzig are among the fastest growing cities in Germany both rising their population over half a million inhabitants again and in strong contrast to the other districts of Saxony.

Saxony-Anhalt had a population of 2,960,000 in 1989, and 2,253,000 in March 2013.[31] The state has a long history of demographic decline: its current territory had a population of 4,100,000 in 1945. The emigration already began during the GDR years.[32]

Thuringia had a population of 2,680,000 in 1989, and 2,166,000 in March 2013.[31] In Thuringia, the migration has less of an impact than the decrease of the fertility rate. Former Minister-President Bernhard Vogel called for a stop to the exodus of skilled workers and young people.[32]

Total change in population of former East Germany is from 15.273 million in 1989, just before reunification, to 12.509 million in 2013, a decrease of 18.1%.

Major cities

| Federal capital | |

| State capital |

| Rank | City | Pop. 1950 |

Pop. 1960 |

Pop. 1970 |

Pop. 1980 |

Pop. 1990 |

Pop. 2000 |

Pop. 2010 |

Area [km²] |

Density per km² |

Growth [%] (2000– 2010) |

surpassed 100,000 |

State (Bundesland) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | | 3,336,026 | 3,274,016 | 3,208,719 | 3,048,759 | 3,433,695 | 3,382,169 | 3,460,725 | 887,70 | 3,899 | 2.32 | 1747 | |

| 2. | | 494,187 | 493,603 | 502,432 | 516,225 | 490,571 | 477,807 | 523,058 | 328,31 | 1,593 | 9.47 | 1852 | |

| 3. | | 617,574 | 589,632 | 583,885 | 562,480 | 511,079 | 493,208 | 522,883 | 297,36 | 1,758 | 6.02 | 1871 | |

| 4. | | 293,373 | 286,329 | 299,411 | 317,644 | 294,244 | 259,246 | 243,248 | 220,84 | 1,101 | −6.17 | 1883 | |

| 5. | | 289,119 | 277,855 | 257,261 | 232,294 | 247,736 | 247,736 | 232,963 | 135,02 | 1,725 | −5.96 | 1890 | |

| 6. | | 260,305 | 261,594 | 272,237 | 289,032 | 278,807 | 231,450 | 231,549 | 200,99 | 1,152 | 0.04 | 1882 | |

| 7. | | 188,650 | 186,448 | 196,528 | 211,575 | 208,989 | 200,564 | 204,994 | 269,14 | 762 | 2.21 | 1906 | |

| 8. | | 133,109 | 158,630 | 198,636 | 232,506 | 248,088 | 200,506 | 202,735 | 181,26 | 1,118 | 1.11 | 1935 | |

| 9. | | 118,180 | 115,004 | 111,336 | 130,900 | 139,794 | 129,324 | 156,906 | 187,53 | 837 | 21.33 | 1939 | |

| Rank | City | Pop. 1950 |

Pop. 1960 |

Pop. 1970 |

Pop. 1980 |

Pop. 1990 |

Pop. 2000 |

Pop. 2010 |

Area [km²] |

Density per km² |

Growth [%] (2000– 2010) |

surpassed 100,000 |

State (Land) |

See also

- Wessi

- East German jokes

References

- ↑ Spiegel Online: Ein Jahr, ein (Un-)Wort! (in German).

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 "Breaking Down the Wall in the Head". Deutsche Welle. 2004-10-03. Retrieved 2009-10-11.

- ↑ Cameron Abadi (07/08-2009). "The Berlin fall". Foreign Policy. Retrieved 2009-10-11. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ 4.0 4.1 "Noch nicht angekommen - Survey of 2900 adults in the New Länder in summer 2008". Berliner Zeitung. 21 January 2009. Retrieved 2009-10-11.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 "East German brands thrive 20 years after end of Communism". Deutsche Welle. 2009-10-03. Retrieved 2009-10-11.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Balmer, Etienne (2009-10-19). "'Women's love lives were better in East Germany before the Berlin Wall fell'". London: Telegraph. Retrieved 2009-10-11.

- ↑ http://www.thelocal.de/society/20110812-36923.html#.UTLa0Dcce0Q

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 "Aufbau Ost, economic reconstruction in the East". Deutsche Bundesregierung. 2007-08-24. Retrieved 2009-10-12.

- ↑ "The Price of a Failed Reunification". Spiegel International. 2005-09-05. Retrieved 2006-11-28.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Boyes, Roger (2007-08-24). "Germany starts recovery from €2,000bn union". London: Times Online. Retrieved 2009-10-12.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 11.5 Kulish, Nicholas (2009-06-19). "In East Germany, a Decline as Stark as a Wall". New York Times. Retrieved October 11, 2009.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Hall, Allan (2007-08-01). "Calls grow to lift burden of Germany's solidarity tax". London: The Independent. Retrieved 2009-10-12.

- ↑ Current statistics of the Bundesagentur für Arbeit comparing east and west

- ↑ "Eastern Germany Less Hard Hit than the West". Spiegel International. Retrieved 2009-10-11.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 "Infrastructure for unified Germany". Federal Government Commissioner for the New Federal States. Retrieved 2009-10-11.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 "Draft Federal Transport Infrastructure Plan" (PDF). United Nations Economic Commission for Europe. Retrieved 2009-10-11.

- ↑ "Firmenprofil". DEGES. Retrieved 2009-10-11.

- ↑ Wilhelm Hinrichs: Die Ostdeutschen in Bewegung – Formen und Ausmaß regionaler Mobilität in den neuen Bundesländern (PDF-Dokument)

- ↑ bpb: Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung: Die DDR in den siebziger Jahren

- ↑ DIE LINKE: Ostdeutschland

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Boyes, Roger (2007-08-20). "Neo-Nazi rampage triggers alarm in Berlin". London: The Times. Retrieved 2009-10-11.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 "Lack of Women in Eastern Germany Feeds Neo-Nazis". Spiegel International. 2007-05-31. Retrieved 2009-10-11.

- ↑ "Right-Wing Extremists Find Ballot-Box Success in Saxony". Spiegel International. 2008-09-06. Retrieved 2009-10-11.

- ↑ "Landtagswahl in Sachsen". Mitteldeutscher Rundfunk. Retrieved 2009-10-22.

- ↑ "Landtagswahl Brandenburg 2009". Tagesschau. Retrieved 2009-10-22.

- ↑ Patrick Donahue. "Skinheads, Neo-Nazis Draw Fury at Dresden 1945 ‘Mourning March’". Retrieved 2009-02-14.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 27.3 27.4 Burke, Jason (2008-01-27). "Slow death of a small German town as women pack up and head west". London: The Guardian. Retrieved 2009-10-11.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 "The Demographic State of the Nation" (PDF). Berlin Institute for Population and Development. 2006. Retrieved 2009-10-11.

- ↑ https://www.destatis.de/EN/FactsFigures/SocietyState/Population/Births/Tables/BirthRate.html

- ↑ http://one-europe.info/eurographics/where-do-young-european-women-go

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 31.2 31.3 31.4 "Gemeinsames Datenangebot der Statistischen Ämter des Bundes und der Länder".

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 32.2 32.3 32.4 "Abwanderung aus den neuen Bundesländern von 1989 bis 2000". Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung. 2001. Retrieved 2009-10-11.