New Zealanders

| |||||||||||||||||

| Regions with significant populations | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

4.25 million | |||||||||||||||||

| 566,815[1] | |||||||||||||||||

| 58,286[2] | |||||||||||||||||

| 22,872[2] | |||||||||||||||||

| 9,475[2] | |||||||||||||||||

| 4,260[2] | |||||||||||||||||

| 4,000[3] | |||||||||||||||||

| 3,146[2] | |||||||||||||||||

| 2,631[4][5] | |||||||||||||||||

| 2,195[2] | |||||||||||||||||

| >2,000[6] | |||||||||||||||||

| Languages | |||||||||||||||||

| English · Māori · NZ Sign Language · Others | |||||||||||||||||

| Religion | |||||||||||||||||

| Predominantly Christianity, mostly Protestantism, but also Roman Catholicism. Other religions include Māori traditional beliefs, Buddhism, Hinduism, Islam, Judaism, and Sikhism. Agnosticism and atheism are also prevalent.[7] | |||||||||||||||||

New Zealanders, colloquially known as Kiwis,[8][9] are citizens of New Zealand. New Zealand is a multiethnic society, and home to people of many national origins. Originally composed solely of the indigenous Māori, the ethnic makeup of the population has been dominated since the 19th century by New Zealanders of European descent, mainly of Scottish, English, Welsh and Irish ancestry, with smaller percentages of other European ancestries such as French, Dutch, Scandinavian and South Slavic. New Zealand had an estimated resident population of around 4.47 million as of June 2013,[10] although around 220,000 of those have been resident in the country for less than five years.[11]

Today, the ethnic makeup of the New Zealand population is undergoing a process of change, with new waves of immigration, higher birth rates and increasing interracial marriage resulting in the New Zealand population of Māori, Asian, Pacific Islander and multiracial descent growing at a higher rate than those of solely European descent, with such groups projected to make up a larger proportion of the population in the future.[12]

While most New Zealanders live in New Zealand, there is also a significant diaspora, estimated in 2001 at over 460,000 or 14% of the international total of New Zealand-born people. Of these, 360,000, over three-quarters of the New Zealand-born population residing outside of New Zealand, live in Australia. Other communities of New Zealanders abroad are concentrated in other English-speaking countries, specifically the United Kingdom, the United States and Canada, with smaller numbers located elsewhere.[2] This diaspora has reportedly surged as of 2010, with well over 650,000 New Zealanders living abroad. According to the Australian Department of Immigration and Border Protection, an estimated 640,770 New Zealanders lived in Australia on 30 June 2013.[1]

History

Polynesian settlers

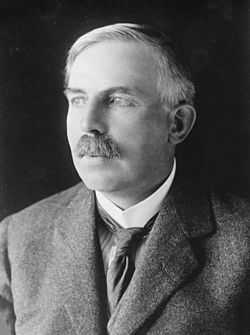

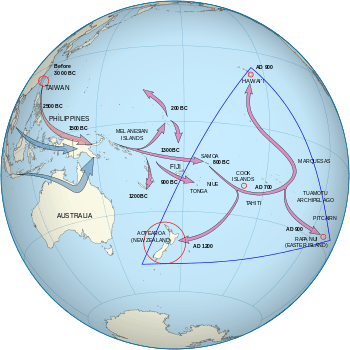

The Māori people are most likely descended from people who emigrated from Taiwan to Melanesia and then travelled east through to the Society Islands.[13] After a pause of 70 to 265 years, a new wave of exploration led to the discovery and settlement of New Zealand in about AD 1250–1300,[14] making New Zealand one of the most recently settled major landmasses. Some researchers have suggested an earlier wave of arrivals dating to as early as AD 50–150; these people then either died out or left the islands.[15][16][17]

Over the following centuries the Polynesian settlers developed into a distinct culture now known as Māori. The population was divided into iwi (tribes) and hapū (subtribes) which would cooperate, compete and sometimes fight with each other. At some point a group of Māori migrated to the Chatham Islands where they developed their distinct Moriori culture.[18][19]

Due to New Zealand's geographic isolation, 500 years passed before the next phase of settlement, the arrival of Europeans. Only then did the indigenous inhabitants need to distinguish themselves from the new arrivals, using the term "Māori" which means "normal" or "ordinary".

The establishment of British colonies in Australia from 1788 and the boom in whaling and sealing in the Southern Ocean brought many Europeans and Americans to the vicinity of New Zealand. Some settled—for economic, religious or personal reasons.

European settlement

The first Europeans known to have reached New Zealand were Dutch explorer Abel Janszoon Tasman and his crew in 1642.[20] Māori killed several of the crew and no Europeans returned to New Zealand until British explorer James Cook's voyage of 1768–71.[20] Cook reached New Zealand in 1769 and mapped almost the entire coastline. Following Cook, New Zealand was visited by numerous European and North American whaling, sealing and trading ships. They traded European food and goods, especially metal tools and weapons, for Māori timber, food, artefacts and water. On occasion, Europeans and Māori traded goods for sex.[21]

The potato and the musket transformed Māori agriculture and warfare, although the resulting Musket Wars died out once the tribal imbalance of arms had been rectified. From the early nineteenth century, Christian missionaries began to settle New Zealand, eventually converting most of the Māori population, although their initial inroads were mainly among the more disaffected elements of society.[22]

Becoming aware of the lawless nature of European settlement and of increasing French interest in the territory, the British government appointed James Busby as British Resident to New Zealand in 1832. Busby failed to bring law and order to European settlement, but did oversee the introduction of the first national flag on 20 March 1834, after an unregistered New Zealand ship was seized in Australia. The nebulous United Tribes of New Zealand later, in October 1835, sent the Declaration of the Independence of New Zealand to King William IV of the United Kingdom, asking him for protection. Ongoing unrest and the legal standing of the Declaration of Independence prompted the Colonial Office to send Captain William Hobson RN to New Zealand to claim sovereignty for the British Crown and negotiate a treaty with the Māori.[i] The Treaty of Waitangi was first signed in the Bay of Islands on 6 February 1840.[23] The drafting was done hastily and confusion and disagreement continue to surround the translation. The Treaty however remains regarded as New Zealand's foundation as a nation and is revered by Māori as a guarantee of their rights.

In response to New Zealand Company attempts to establish a separate colony in Wellington, and French claims in Akaroa, Hobson, now Lieutenant-Governor, declared British sovereignty over all of New Zealand on 21 May 1840. The two proclamations published in the New Zealand Advertiser and Bay Of Islands Gazette issue of 19 June 1840 "assert[s] on the grounds of Discovery, the Sovereign Rights of Her Majesty over the Southern Islands of New Zealand, commonly called 'The Middle Island' (South Island) and 'Stewart's Island' (Stewart Island/Rakiura); and the Island, commonly called 'The Northern Island', having been ceded Sovereignty to Her Majesty." The second proclamation expanded on how sovereignty over the "Northern Island" had been ceded under the treaty signed that February.[24]

Following the formalising of sovereignty, the organised and structured flow of migrants from Great Britain and Ireland began, and by 1860 more than 100,000 British and Irish settlers lived throughout New Zealand. The Otago Association actively recruited settlers from Scotland, creating a definite Scottish influence in that region, while the Canterbury Association recruited settlers from the south of England, creating a definite English influence over that region.[25] By 1870 the non-Māori population reached over 250,000.[26]

Other settlers came from Germany, Scandinavia, and other parts of Europe as well as from China and the Indian subcontinent, but British and Irish settlers made up the vast majority, and did so for the next 150 years.

Between 1881 and the 1920s, the Parliament of New Zealand passed legislation that intended to limit Asiatic migration to New Zealand, and prevented Asians from naturalising.[27] In particular, the New Zealand government levied a poll tax on Chinese immigrants up until the 1930s, when Japan went to war with China. New Zealand finally abolished the poll tax in 1944.

An influx of Jewish refugees from central Europe came in the 1930s.

Many of the persons of Polish origin in New Zealand arrived as orphans from Eastern Poland via Siberia and Iran in 1944 during World War II.[28]

Post-Second World War immigration

With the agencies of the United Nations dealing with humanitarian efforts following the Second World War, New Zealand accepted about 5,000 refugees and displaced persons from Europe, and more than 1,100 Hungarians between 1956 and 1959 (see Refugee migration into New Zealand). The post-WWII immigration included more persons from Greece, Italy and the former Yugoslavia.

New Zealand limited immigration to those who would meet a labour shortage in New Zealand. To encourage those to come, the Government introduced free and assisted passages in 1947, a schema expanded by the National Party administration in 1950. However, when it became clear that not enough skilled migrants would come from the British Isles alone, recruitment began in Northern European countries. New Zealand signed a bilateral agreement for skilled migrants with the Netherlands, and a large number of Dutch immigrants arrived in New Zealand. Others came in the 1950s from Denmark, Germany, Switzerland and Austria to meet needs in specialised occupations.

By the 1960s, the policy of excluding people based on nationality yielded a population overwhelmingly European in origin. By the mid-1960s, a desire for cheap unskilled labour led to ethnic diversification. In the 1950s and 1960s, New Zealand encouraged migrants from the South Pacific. The country had a large demand for unskilled labour in the manufacturing sector. As long as this demand continued, migrants were encouraged by the government to come from the South Pacific, and many overstayed. However, when the boom times stopped, some blamed the migrants for the economic downturn affecting the country, and many of those people suffered dawn raids from 1974.

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Australian Department of Immigration and Border Protection (2 January 2014). "Fact Sheet 17 – New Zealanders in Australia". Retrieved 14 February 2014.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 John Bryant and David Law (September 2004). "New Zealand’s Diaspora and Overseas-born Population: The diaspora". New Zealand Treasury. Retrieved 10 August 2010.

- ↑ Matthew Chung (6 November 2009). "From F1 to Fifa, the show rolls on". The National. Retrieved 11 August 2010.

- ↑ "Anzahl der Ausländer in Deutschland nach Herkunftsland (Stand: 31. Dezember 2014)".

- ↑ https://www.destatis.de/DE/Publikationen/Thematisch/Bevoelkerung/MigrationIntegration/AuslaendBevoelkerung.html?nn=68748

- ↑ http://www.nzembassy.com/hong-kong/new-zealanders-overseas/living-hong-kong

- ↑ See the article entitled Religion in New Zealand.

- ↑ Gary Morley (24 June 2010). "Kiwis hope to take flight at World Cup". CNN. Retrieved 11 August 2010.

- ↑ "Kiwi and people: early history". Te Ara Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 11 August 2010.

- ↑ "National Population Estimates: At 30 June 2013". Statistics New Zealand. 14 August 2013. Retrieved 24 May 2014.

- ↑ "2013 Census QuickStats about culture and identity". Statistics New Zealand. 15 April 2014. Retrieved 24 May 2014.

- ↑ Gillian Smeith and Kim Dunstan (June 2004). "Ethnic Population Projections: Issues and Trends". Statistics New Zealand. Retrieved 10 August 2010.

- ↑ Wilmshurst, J. M.; Hunt, T. L.; Lipo, C. P.; Anderson, A. J. (2010). "High-precision radiocarbon dating shows recent and rapid initial human colonization of East Polynesia". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 108 (5): 1815. Bibcode:2011PNAS..108.1815W. doi:10.1073/pnas.1015876108.

- ↑ Irwin, Geoff; Walrond, Carl (4 March 2009). "When was New Zealand first settled? – The date debate". Te Ara Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 14 February 2010.

- ↑ Mein Smith (2005), pg 6.

- ↑ Lowe, David J. (2008). Lowe, David J., ed. Guidebook for Pre-conference North Island Field Trip A1 ‘Ashes and Issues’ (28–30 November 2008). Australian and New Zealand 4th Joint Soils Conference, Massey University, Palmerston North (1–5 December 2008) (PDF). New Zealand Society of Soil Science. pp. 142–147. ISBN 978-0-473-14476-0. Retrieved 14 February 2010.

- ↑ Sutton et al. (2008), pg 109. "This paper ... affirms the Long Chronology [first settlement up to 2000 years BP], recognizing it as the most plausible hypothesis."

- ↑ Clark (1994) pg 123–135

- ↑ Davis, Denise (11 September 2007). "The impact of new arrivals". Te Ara Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 30 April 2010.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Mein Smith (2005), pg 23.

- ↑ King (2003) pg 122.

- ↑ Peggy Brock, ed. Indigenous Peoples and Religious Change. Leiden: Brill, 2005. ISBN 978-90-04-13899-5. pages 67–69

- ↑ Political and constitutional timeline, New Zealand History online, Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Updated 6 December 2009. Retrieved 30 April 2010.

- ↑ "New Zealand Advertiser and Bay Of Islands Gazette, 19 June 1840". Hocken Library. Retrieved 22 April 2010.

- ↑ "History of Immigration - 1840 - 1852".

- ↑ "History of Immigration - 1853 - 1870".

- ↑ "1881–1914: restrictions on Chinese and others". Te Ara Encyclopedia of New Zealand.

- ↑ "Polish Orphans". Te Ara. 16 November 2012.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to People of New Zealand. |

- Demographics of New Zealand’s Pacific Population—Statistics New Zealand

- Population clock—Statistics New Zealand

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||