New Chronology (Rohl)

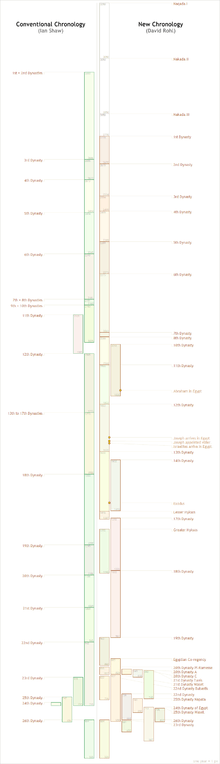

New Chronology is an alternative Chronology of the ancient Near East developed by English Egyptologist David Rohl and other researchers[1][2] beginning with A Test of Time: The Bible - from Myth to History in 1995. It contradicts mainstream Egyptology by proposing a major revision of the conventional chronology of ancient Egypt, in particular by redating Egyptian kings of the 19th through 25th Dynasties, lowering conventional dates up to 350 years. Rohl asserts that the New Chronology allows him to identify some of the characters in the Old Testament with people whose names appear in archaeological finds.

The New Chronology, one of several proposed radical revisions of the conventional chronology, has not been accepted in academic Egyptology, where the conventional chronology or small variations of it remain standard.[3] Professor Amélie Kuhrt, head of Ancient Near Eastern History at University College, London, in one of the standard reference works of the discipline, notes that "Many scholars feel sympathetic to the critique of weaknesses in the existing chronological framework[...], but most archaeologists and ancient historians are not at present convinced that the radical redatings proposed stand up to close examination."[4] Rohl's most vocal critic has been Professor Kenneth Kitchen, one of the leading experts on biblical history and the author of the standard work on the conventional chronology of the Egyptian Third Intermediate Period, the period most directly affected by the New Chronology's redating of the 19th to 25th dynasties.

Rohl's New Chronology

David Rohl's published works A Test of Time (1995), Legend (1998), The Lost Testament (2002), and The Lords of Avaris (2007) set forth Rohl's theories for redating the major civilisations of the ancient world. A Test of Time proposes a down-dating (bringing closer to the present), by several centuries, of the Egyptian New Kingdom, thus requiring a major revision of the conventional chronology of ancient Egypt. Rohl asserts that this would permit scholars to identify some of the major events in the Old Testament with events in the archaeological record, and identify some of the well-known biblical characters with historical figures who appear in contemporary ancient texts. Lowering the Egyptian dates also dramatically affects the dating of dependent chronologies, such as that currently employed for the Greek "Heroic Age" of the Late Bronze Age, removing the Greek Dark Age and lowering the dates of the Trojan War to within a couple of generations of a 9th-century-BC Homer and his most famous composition: The Iliad.

Rejecting the Revised Chronology of Immanuel Velikovsky and the Glasgow Chronology presented at the Society for Interdisciplinary Studies's 1978 "Ages in Chaos" conference, the New Chronology lowers the Egyptian dates (established within the traditional chronology) by up to 350 years at points prior to the universally accepted fixed date of 664 BC for the sacking of Thebes by Ashurbanipal.

Prior to the 1995 publication of A Test of Time, Thomas L. Thompson, a theologian associated with the Copenhagen School, had insisted that any attempt to write history based on a direct integration of biblical and extra-biblical sources was "not only dubious but wholly ludicrous".[5] Rohl explained his view on the issue in The Lost Testament (2007): "Is the Old Testament history or myth? The only way to answer that question is to investigate the biblical stories using the archaeological evidence, combined with a study of the ancient texts of the civilisations which had a role to play in the Bible story. But this has to be done with an open mind. In my view the biblical text – just like any other ancient document – should be treated as a potentially reliable historical source until it can be demonstrated to be otherwise."[6] Rohl had previously remarked in A Test of Time (1995) that he "did not originally set out to challenge our current understanding of the Old Testament narratives. This has come about simply because of the need to explore the ramifications of my TIP [Egyptian Third Intermediate Period] research. I have no religious axe to grind – I am simply an historian in search of some historical truth."[7]

Rohl's redating is based on criticism of three of the four arguments which he considers are the original foundations of the conventional chronology for the Egyptian New Kingdom:

- He asserts that the identification of "Shishaq [Shishak], King of Egypt" (1 Kings 14:25f; 2 Chronicles 12:2-9) with Shoshenq I, first proposed by Jean-François Champollion, is based on incorrect conclusions. Rohl argues instead that Shishaq should be identified with Ramesses II (probably pronounced Riamashisha), which would move the date of Ramesses' reign forward some 300 years.

- Rohl also asserts that the record in the Ebers papyrus of the rising of Sirius in the ninth regnal year of Amenhotep I, which is used in conventional chronology to fix that year to either 1542 BC or 1517 BC, has been misread, and instead should be understood as evidence for a reform in the Egyptian calendar. This negative view of Papyrus Ebers is exemplified in a statement by Professor Jürgen von Beckerath who is of the opinion that "The calendar on the verso of the Ebers Medical Papyrus is by now so disputed that we must ask ourselves whether we really possess a sure basis for the chronology of this period of Egyptian history which is, after all, of the greatest importance for fixing the sequence of historical events, as well as for neighbouring countries".[8] Professor Wolfgang Helck concludes that "We therefore think it is safer to start from the regnal dates rather than from interpretations of real or supposed Sirius (Sothic) or New Moon dates".[9]

- Papyrus Leiden I.350, which dates to the 52nd year of Ramesses II, records a lunar observation which places that year of Ramesses' reign in one of 1278, 1253, 1228 or 1203 BC within the date-range of the conventional chronology. Having questioned the value of the Ebers Papyrus, Rohl argues that, since the lunar cycle repeats itself every twenty-five years, it is only useful for fine tuning a chronology and could equally apply to dates 300 years later as in the New Chronology.

Thus, Rohl is of the opinion that none of these three foundations of the conventional Egyptian chronology are secure, and that the sacking of Thebes by the Assyrian king Ashurbanipal in 664 BC is the earliest fixed date in Egyptian history.

Evidence adduced

Rohl bases his revised chronology (the New Chronology) on his interpretation of numerous archeological finds and genealogical records from Egypt. For example:

- Rohl notes that no Apis bull burials are recorded in the Lesser Vaults at Saqqara for the 21st and early 22nd dynasties of Egypt. He also argues that the reburial sequence of the mummies of the New Kingdom pharaohs in the Royal Cache (TT 320) indicates that these two dynasties were contemporary (thus explaining why there are insufficient Apis burials for the period). Rohl finds confirmation of this scenario of parallel dynasties in the royal burial ground at Tanis where it appears that the tomb of Osorkon II of the 22nd Dynasty was built before that of Psusennes I of the 21st Dynasty. In Rohl's view this can only be explained if the two dynasties were contemporary.

- Rohl offers inscriptions that list three non-royal genealogies which, when one attributes 20 to 23 years to a generation, show, according to Rohl, that Ramesses II flourished in the 10th century BC as Rohl advocates. In the conventional chronology, all three genealogies would be missing seven generations. He also argues that there are no genealogies that confirm the conventional dates for Ramesses II in the 13th century BC.

- One of Rohl's methods is the use of archaeo-astronomy, which he employs to fix the date of a near-sunset solar eclipse during the reign of Amenhotep IV and observed from the city of Ugarit. Based on calculations, using computer astronomy programs, Rohl asserts that the only time when this eclipse could have occurred during the whole second millennium BC was on 9 May 1012 BC. This is approximately 350 years later than the conventional dates for Amenhotep IV (Akhenaton) (1353-1334 BC).

- Rohl's dates for Amenemhat III of the 12th Dynasty in the 17th century BC, has found support in the work of astronomer David Lappin whose research finds matches for a sequence of 37 out of 39 lunar month lengths recorded in 12th Dynasty contracts. The conventional chronology, on the other hand, matches at best 21. According to Lappin, this pattern provides "startling" support for Rohl's chronology.[5]

Shishaq

Most Egyptologists accept Shishaq as an alternative name for Shoshenq I.[10][11][12] Rohl disputes that Shoshenq's military activity fits the biblical account of Shishaq on the grounds that the two kings' campaigns are completely different and Jerusalem does not appear in the Shoshenq inscription as a subjected town.[13] He also points out that Ramesses did campaign against Israel and that he had a short form of his formal name which was in use in Palestine.[14] That name was Sysw, whilst the early Hebrew alphabet did not distinguish between S and SH, so the biblical name may have originally been Sysq. Rohl has also argued that the qoph ending may be a later misreading of the early sign for waw which in the 10th century was identical to the 7th century sign for qoph. Thus 7th century Sysq may have been a mistaken later reading of 10th century Sysw.[15]

The theory that Ramesses II (hypocoristicon 'Sysa'), rather than Shoshenq I, should be identified with the biblical Shishak is not widely accepted.[16] On the other hand, there are several scholars (Bimson, Hornung, Furlong, etc.) who do question the reliance of Egyptian chronology on such a crucial identification as that of Shoshenq with Shishaq. Rohl argues that, on methodological grounds, the internal Egyptian chronology of the Third Intermediate Period should not be dependent on a biblical date to establish the foundation date of the 22nd Dynasty.

Dr. Pierce Furlong challenges Kitchen's dismissal of the lack of historical correspondence between the campaigns of Shoshenq and Shishaq raised by both Rohl and Dr John Bimson:

Kitchen dismisses the apparent discrepancy between the Shoshenq I campaign itinerary and the Old Testament (OT) account of Shishak’s activities as ‘frivolous and exaggerated’. … he argues that since Shoshenq’s topographical list is incomplete, Jerusalem (and presumably every other important fortified town in Judah) may have been lost in a lacuna. However, the attention paid by numerous scholars to the fact that not a single highland Judean town appears in the Karnak list would indicate that this matter is hardly frivolous or exaggerated.[17]

One scholar, Kevin Wilson, agrees only partially with David Rohl. Wilson accepts that there is a mismatch between the triumphal relief of Shoshenq I and the biblical description of King Shishak. However, he does not think that this discrepancy gives sufficient reason for doubting the identification of Shoshenq I with King Shishak of the Bible. Wilson writes about Shoshenq's inscription, "Contrary to previous studies, which have interpreted the relief as a celebration of his Palestine campaign, neither the triumphal relief nor any of its elements can be utilized as a source for historical data about that campaign. … the triumphal relief can unfortunately play no role in the reconstruction of Shoshenq’s campaign."[18]

However, Wilson's view is not supported by Kenneth Kitchen who states: "That the great topographical list of Shoshenq I at Karnak is a document of the greatest possible value for the history and nature of his campaign against Judah and Israel is now clearly established beyond all dispute, thanks to the labours expended on that list by a series of scholars. However, the composition and interpretation of the list still require further examination and clarification".[19] Other leading scholars who have studied the campaign relief point out that it is indeed a unique list of subjected towns and not a copy of an earlier campaign by a more celebrated pharaoh.[20][21][22][23] This originality makes it far more likely that it is a true representation of cities and locations brought under Egyptian control by the military activities of Shoshenq I.

Implications of the New Chronology

The implications of a radical down-dating of the conventional Egyptian chronology, such as that proposed by Rohl and other revisionists, are complex and wide-ranging. The New Chronology affects the historical disciplines of Old Testament studies, Levantine archaeology, Aegean and Anatolian archaeology and Classical studies, whilst raising major issues concerning Mesopotamian chronology and its links with both Egypt and Anatolia.

Implications for Egypt and her Neighbours

Redating the reign of Ramesses II to three centuries later than that given by the conventional chronology would not only reposition the date of the Battle of Kadesh and revise the linked chronology of Hittite history, it would also require a revision of the chronology of Assyrian history prior to 911 BC. Given the dependence of Hittite chronology on Egyptian chronology,[24] a lowering of Egyptian dates would result in a lowering of the end of the Hittite New Kingdom and a resulting reduction (or complete removal) of the Anatolian Dark Age.[25]

During the Amarna period, a chronological synchronism between Egypt and Assyria is attested through the correspondence of Pharaoh Akhenaten and a King Ashuruballit. In the conventional chronology, this Ashuruballit is identified with Ashuruballit I of the early Middle Assyrian period, whilst the New Chronology has proposed the addition of an otherwise unknown Ashuruballit "II" during the Middle Assyrian "dark age" as the author of the Amarna letters. New Chronologist Bernard Newgrosh argues that such a hypothesis is plausible because the Ashuruballit of the Amarna letter gives a different name for his father than is given for Ashuruballit I in the Assyrian King List, and that the historical setting recorded in the annals of the early Middle Assyrian ruler differs from information gleaned from the Amarna correspondent’s letters.[26] Given that the Ashuruballit I synchronism with Akhenaten has become the crucial link between Egyptian and Mesopotamian history in recent years, this issue is a key area of focus and dispute.[27]

Implications for the Old Testament

As explained above, the New Chronology rejects the identification of Shoshenq I with the biblical Shishaq,[28] and instead offers Ramesses II (also known by his nickname "Sysa") as the real historical figure behind the Shishaq narrative.

Rohl identifies Labaya, a local ruler in Canaan whose activities are documented in the Amarna Letters, with King Saul, and identifies King David with Dadua ("Tadua"), also mentioned in Amarna Letter EA256. Saul and Labaya share the same demise - "both die in battle - against a coalition of city states from the coastal plain - on or near Mount Gilboa, both as a result of betrayal."[5] Both also have a surviving son whose name translates as "Man of Baal."

The New Chronology places King Solomon at the end of the wealthy Late Bronze Age, rather than in the relatively impoverished Early Iron Age, as in the conventional chronology. Rohl and other New Chronology researchers contend that this fits better with the Old Testament description of Solomon's wealth.[5]

Furthermore, Rohl shifts the Israelite Sojourn, Exodus and Conquest from the end of the Late Bronze Age to the latter part of the Middle Bronze Age (from the Egyptian 19th Dynasty to the 13th Dynasty and Hyksos period). Rohl claims that this solves many of the problems associated with the historicity issue of the biblical narratives. He makes use of the archaeological reports from Tell ed-Daba (ancient Avaris), in the Egyptian eastern delta, which show that a large Semitic-speaking population lived there during the 13th Dynasty. These people were culturally similar to the population of Middle-Bronze-Age (MB IIA) Canaan. Rohl identifies these Semites as the people upon whom the biblical tradition of the Israelite Sojourn in Egypt was subsequently based.

Towards the end of the Middle Bronze Age (late MB IIB) archaeologists have revealed a series of city destructions which John Bimson and Rohl have argued correspond closely to the cities attacked by the Israelite tribes in the Joshua narrative.[29][30] Most importantly, the heavily fortified city of Jericho was destroyed and abandoned at this time. On the other hand, there was no city of Jericho in existence at the end of the Late Bronze Age, drawing William Dever to conclude that, "Joshua destroyed a city that wasn’t even there".[31] Rohl claims that it is this lack of archaeological evidence to confirm biblical events in the Late Bronze Age which lies behind modern scholarly skepticism over the reliability of the Old Testament narratives before the Divided Monarchy period. He gives the example of Israeli professor of archaeology, Ze'ev Herzog, who caused an uproar in Israel and abroad when he gave voice to the "fairly widespread" view held amongst his colleagues that "there had been no Exodus from Egypt, no invasion by Joshua and that the Israelites had developed slowly and were originally Canaanites,"[32] concluding that the Sojourn, Exodus and Conquest was “a history that never happened.”[32] However, Rohl contends that the New Chronology, with the shift of the Exodus and Conquest events to the Middle Bronze Age, removes the principal reason for that widespread academic skepticism.

Identifications in the New Chronology

Personal identifications

Rohl identifies:

- Nebkaure Khety IV (16th Pharaoh of the 10th Dynasty) with the Pharaoh who had dealings with Abraham.

- Amraphel (Genesis 14) with Amar-Sin, king of Kish in Sumer (1834-1825 BC/BCE by Rohl's chronology).

- Tidal (Bible), King of Goyim/King of Nations (Genesis 14), with Tishdal, Hurrian ruler from the Zagros mountains.

- Zariku, governor of Ashur, with king Arioch of Ellasar.

- Kutir-Lagamar of Elam with Chedorlaomer of Elam.

- Amenemhat III with the Pharaoh of Joseph, and Joseph with the Vizier of Amenemhat III.

- The "new king who did not know Joseph" in Exodus 1:8 is identified by Rohl with Sobekhotep III.

- Neferhotep I with the adoptive grandfather of Moses.

- Khanefere Sebekhotep IV, brother and successor of Neferhotep, with Khenephres, the Pharaoh from whom Moses fled to Midian.

- The Pharaoh of the Exodus with Tutimaios, known also as Dudimose.

- Ibni, Middle Bronze Age ruler of Hazor, with Jabin, king of Hazor in Joshua 11:10.

- Akish or Achish, king of Gath, is identified with Šuwardata, King of Gath in the Amarna letters. Akish is believed to be a shortened form of the Hurrian name Akishimige, "the Sun God has given." Shuwardata is an Indo-European name meaning "the Sun God has given."

- Aziru of the Amarna Letters is identified with Hadadezer, Syrian king in II Samuel.

- Labaya, a ruler in the Amarna Letters, with King Saul.

- King David with Dadua in Amarna Letter EA256.

- Mutbaal, writer of the letter, is identified with Ishbaal (aka Ishbosheth). The two names have exactly the same meaning: "Man of Baal." Following the death of his father (Labaya/Saul), Mutbaal/Ishbaal moved his center to Transjordan.

- "The Sons of Labaya," in the Amarna Letters (EA 250), with Mutbaal/Ishbaal and David/Dadua, the latter being the son-in-law of Labaya/Shaul.

- Benemina, also mentioned in EA256, is identified by Rohl with Baanah, Israelite chieftain in II Samuel 4, who would later betray and assassinate Ishbosheth.

- Yishuya, also mentioned in EA256, is identified with Jesse (Ishai in Hebrew), father of David.

- Ayab, the subject of EA 256, is held to be the same as the Biblical Yoav (English "Joab").

- Lupakku ("Man of Pakku"), Aramean army commander in the Amarna Letters, with Shobach ("He of Pakku"), Aramean army commander in the Bible.

- Nefertiti with Neferneferuaten and with Smenkhkare.

- Horemheb is identified with the Pharaoh who destroyed Gezer and later gave it to Solomon, together with one of his daughters as a wife. When Horemhab took Gezer he was not yet the ruler, but was acting under Tutankhamun. However, he became Pharaoh not long after, and Tutankhamun died too young to have left any marriageable daughters.

- Ramses II (hypocoristicon = Shysha) with Shishaq in the Bible.

- Irsu the Syrian, who took over control of Egypt according to the Harris Papyrus, with Arza, Master of the Palace of Israel according to I Kings 16:8-10.

- Sheshi, a Hyksos ruler, with Sheshai, a ruler of Hebron descended from Anak (Joshua 15:13-15).

- Io of the Line of Inachus with Queen Ahhotep of the 17th Dynasty of Egypt at Waset

- Cadmus of Thebes with Cadmus in the line of Pelasgian rulers of Crete

- Inachus with Anak-idbu Khyan of the Greater Hyksos

- Auserre Apepi of the Greater Hyksos with Epaphus

- Cush, son of biblical Ham with Meskiagkasher of the First Dynasty of Uruk

- Nimrod, son of biblical Cush with Enmerkar ('Enmer the Hunter') of the First Dynasty of Uruk

Geographical identifications

Rohl, in addition to his chronology, also has some geographical ideas that are different from the conventional notions. These include:

- The Garden of Eden, according to Rohl, was located in what is now northwestern Iran, between Lake Urmia and the Caspian Sea.[33]

- The Tower of Babel, according to Rohl, was built in the ancient Sumerian capital of Eridu.[34]

- The site of the ancient city of Sodom is "a little over 100 metres beneath the surface of the Dead Sea," a few kilometers south-by-southeast from En-Gedi.[35]

- The Amalekites defeated by King Saul were not the ones living in the Negev and/or the Sinai, but a northern branch of this people, "in the territory of Ephraim, on the highlands of Amalek" - or, in an alternative translation "in the Land of Ephraim, the mountains of the Amalekites" (Judges 12:15). This is supported by the report that, immediately following his destruction of the Amalekites, "Saul went to Carmel and set up a monument" (I Samuel 15:12). Once Saul is removed from the Negev and the Sinai, "Saul's kingdom as described in the Bible is precisely the area ruled over by Labaya according to the el-Amarna letters."[36]

Rohl's revised chronology of Pharaohs

Dates proposed by Rohl for various Egyptian monarchs, all dates BCE (NC=New Chronology, OC=Orthodox/conventional Chronology):

| Name | Notes | NC from | NC to | OC from | OC to |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Khety IV | Pharaoh whom Abraham visited | 1876 | 1847 | ||

| Abraham in Egypt | 1853 | ||||

| Amenemhat I | 1800 | 1770 | 1985 | 1956 | |

| Amenemhat III | 1682 | 1637 | 1831 | 1786 | |

| Joseph appointed vizier | 1670 | ||||

| Wegaf | 1632 | 1630 | |||

| Sobekhotep III | Enslaved the Israelites | 1568 | 1563 | ||

| Sobekhotep IV | Moses fled from him | 1530 | 1508 | ||

| Dudimose | The Exodus took place in 1447 | 1450 | 1446 | ||

| Sheshi | 1416 | 1385 | |||

| Nehesy | 1404 | 1375 | |||

| Shalek | First of the major Hyksos rulers | 1298 | 1279 | ||

| Khyan | 1255 | 1226 | |||

| Apepi | 1209 | 1195 | |||

| Ahmose I | The end of the Hyksos rule at Avaris took place in 1183 | 1194 | 1170 | 1550 | 1525 |

| Amenhotep I | 1170 | 1150 | 1525 | 1504 | |

| Amenhotep IV Akhenaten | 1022 | 1007 | 1352 | 1336 | |

| Ugarit Eclipse | 1012 | ||||

| Tutankhamun | 1007 | 998 | 1336 | 1327 | |

| Horemheb | 990 | 962 | 1323 | 1295 | |

| Ramesses II | Shishak, King of Egypt (1 Kings 14:25f; 2 Chronicles 12:2-9) | 943 | 877 | 1279 | 1213 |

| Battle of Qadesh | 939 | ||||

| Merneptah | 888 | 875 | 1213 | 1203 | |

| Shoshenq I | 823 | 803 | 945 | 924 | |

| Herihor | 823 | 813 | |||

| Shoshenq II | 765 | 762 | |||

| Taharqa | 690 | 664 |

Reception

In Egyptology

Egyptologists have not adopted the New Chronology,[3] continuing to employ the standard chronology in mainstream academic and popular publications. Rohl's most vocal critic has been Professor Kenneth Kitchen, formerly of Liverpool University, who called Rohl's thesis "100% nonsense."'.[37] By contrast, other Egyptologists recognise the value of Rohl's work in challenging the bases of the Egyptian chronological framework. Professor Eric Hornung acknowledges that "...there remain many uncertainties in the Third Intermediate Period, as critics such as David Rohl have rightly maintained; even our basic premise of 925 [BC] for Shoshenq’s campaign to Jerusalem is not built on solid foundations."[38] Academic debate on the New Chronology, however, has largely not taken place in Egyptological or archaeological journals. Most discussions are to be found in the Institute for the Study of Interdisciplinary Sciences' Journal of the Ancient Chronology Forum (1985–2006),[39] which specialised in the chronological issues generally neglected in mainstream Egyptology.[40]

Chris Bennett (1996),[3] while saying "I am quite certain that Rohl’s views are wrong" notes that besides academic debate on problems with the conventional chronology, such as those associated with the Thera eruption, a "far deeper challenge ... has been mounted in the public arena." The history of this challenge to mainstream consensus outside of academic debate originates with the 1991 Centuries of Darkness by Peter James, together with Rohl, co-founder of the Institute for the Study of Interdisciplinary Sciences. Centuries of Darkness postulated 250 years of non-existent "phantom time" in the conventional chronology based on an archaeological "Dark Age".[41]

Kenneth Kitchen's arguments against the New Chronology have focused on Rohl's Third Intermediate Period revision which proposes an overlap between the 21st and 22nd Dynasties. In particular Kitchen challenges the validity of the chronological anomalies raised by Rohl, questioning whether they are true anomalies and offering his own explanations for the apparent problems raised by Rohl. Kitchen accuses New Chronologists of being obsessed with trying to close gaps in the archaeological record by lowering the dating.

Grouping all radical revisions of Egyptian chronology together without distinction, Erik Hornung, in his Introduction to the Handbook of Ancient Egyptian Chronology, makes the following statement:

We will always be exposed to such attempts, but they could only be taken seriously if not only the arbitrary dynasties and rulers, but also their contexts, could be displaced.... In the absence of such proofs we can hardly be expected to "refute" such claims, or even to respond in any fashion ... It is thus neither arrogance nor ill-will that leads the academic community to neglect these efforts which frequently lead to irritation and distrust outside of professional circles (and are often undertaken with the encouragement of the media). These attempts usually require a rather lofty disrespect of the most elementary sources and facts and thus do not merit discussion. We will therefore avoid discussion of such issues in our handbook, restricting ourselves to those hypotheses and discussions which are based on the sources.[42]

Bennett (1996), whilst not accepting Rohl's thesis, suggests that such out-of-hand rejection may be inappropriate in Rohl's case, since "there is a world of difference between [Rohl's] intellectual standing and that of Velikovsky, or even Peter James" since, unlike "popular radicalisms" such as those of Velikovsky, Bauval or Hancock, "Rohl has a considerable mastery of his material."

Professor Amélie Kuhrt, head of Ancient Near Eastern History at University College, London, in one of the standard reference works of the discipline, states:

An extreme low chronology has been proposed recently by a group devoted to revising the absolute chronology of the Mediterranean and Western Asia: P. James et al., Centuries of Darkness, London, 1991; similar, though slightly diverging revisions, are upheld by another group, too, and partly published in the Journal of the Ancient Chronology Forum. The hub for the dating of other cultures is Egypt, so much of the work of both groups focuses on Egyptian evidence. Many scholars feel sympathetic to the critique of weaknesses in the existing chronological framework presented in these volumes, but most archaeologists and ancient historians are not at present convinced that the radical redatings proposed stand up to close examination.[4]

Radiocarbon dating

In 2010 a series of corroborated radiocarbon dates were published for dynastic Egypt which suggest some minor revisions to the conventional chronology, but do not support Rohl's proposed revisions.[43]

In popular media

In 1995 Rohl published his version of the New Chronology, in the best-selling book A Test of Time, accompanied by a 1995 Channel 4 three-part series Pharaohs and Kings - A Biblical Quest. A Test of Time takes up the general scenario presented by James, adding many details omitted in 1991, including the "dramatic results" pertaining to Biblical chronology. Whilst the New Chronology has not been broadly accepted in academia, it has been widely disseminated to the public since the 1990s via Rohl's best-selling[44] books and a 1995 Channel 4 television documentary, aired in the United States in 1996 on The Learning Channel. Berthoud (2008) contrasts the "near-unanimous" rejection of Rohl's theories in Egyptology with the "sensational effect" his books, combined with the television series, had on the general public.[45]

The reaction of some leading figures from the academic establishment has been very hostile. Kenneth Kitchen presented a "savage review" of Centuries of Darkness in the Times Literary Supplement, and the British Museum banned A Test of Time from its museum store.[46]

By evangelicals

In December 1999 the Dutch language internet journal Bijbel, Geschiedenis en Archeologie (Bible, History and Archaeology) devoted space to a debate about Rohl's New Chronology. According to evangelical scholar, J.G. van der Land, editor of the journal, Rohl's time-line resolves some archaeological anomalies surrounding ancient Egypt, but creates conflicts with other areas that make it untenable.[47] His arguments were then countered by Peter van der Veen and Robert Porter.[48][49] In the final article in the issue, van der Land identified some new issues for Rohl's chronology arising from recent finds in Assyrian letters.[50] A detailed response to van der Land's criticisms has been published by Bernard Newgrosh in his volume on Mesopotamian chronology Chronology at the Crossroads: The Late Bronze Age in Western Asia published in 2007.[51]

Sources

- Rohl, David (1995). A Test of Time: The Bible - from Myth to History. London: Century. ISBN 0-7126-5913-7. Published in the U.S. as Rohl, David (1995). Pharaohs and Kings: A Biblical Quest. New York: Crown Publishers. ISBN 0-517-70315-7.

- Rohl, David (1998). Legend: The Genesis of Civilisation. London: Century. ISBN 0-7126-7747-X.

- Rohl, David (2002). The Lost Testament: From Eden to Exile - The Five-Thousand-Year history of the People of the Bible. London: Century. ISBN 0-7126-6993-0. Published in paperback as Rohl, David (2003). From Eden to Exile: The Epic History of the People of the Bible. London: Arrow Books Ltd. ISBN 0-09-941566-6.

- Van der Veen, Peter; Zerbst, Uwe (2004). Biblische Archäologie Am Scheideweg?: Für und Wider einer Neudatierung archäologischer Epochen im alttestamentlichen Palästina. Holzgerlingen, Germany: Haenssler-Verlag GmbH. ISBN 978-3-7751-3851-2.

- Rohl, David (2007). The Lords of Avaris: Uncovering the Legendary Origins of Western Civilisation. London: Century. ISBN 0-7126-7762-3.

- Newgrosh, Bernard (2007). Chronology at the Crossroads: The Late Bronze Age in Western Asia. Leicester: Troubador Publishing. ISBN 978-1-906221-62-1.

References

- ↑ Rohl, David (2002). The Lost Testamen. UK.

- ↑ Rohl, David (2009). From Eden to Exile. USA. p. 2.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Bennett, Chris (1996). "Temporal Fugues". Journal of Ancient and Medieval Studies XIII.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Kuhrt, Amelie (1995). The Ancient Near East c. 3000-330 BC. Routledge History of the Ancient World series I. London & New York. p. 14.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 The Sunday Times, 13 October 2002, How myth became history

- ↑ The Lost Testament, p. 3

- ↑ A Test of Time, p. 11

- ↑ Becherath, J. von, in Helk, W. (ed.) Abstracts for the 'High, Middle or Low? International Colloquium on Chronology held at Schloss Haindorf (1990), p. 5

- ↑ Helck, W. in Helk, W. (ed.) Abstracts for the 'High, Middle or Low? International Colloquium on Chronology held at Schloss Haindorf (1990), p. 21

- ↑ Ash, Paul S. David, Solomon and Egypt Continuum International Publishing Group - Sheffie (1 Nov 1999) ISBN 978-1-84127-021-0 pp. 30-31

- ↑ Coogan, Michael David The Oxford History of the Biblical World Oxford Paperbacks; New edition (26 Jul 2001) ISBN 978-0-19-513937-2 p. 175

- ↑ Wilson, Kevin A The Campaign of Pharaoh Shoshenq I into Palestine Mohr Siebeck 2005 ISBN 978-3-16-148270-0 p.1

- ↑ A Test of Time, pp. 122-27.

- ↑ The Lost Testament, pp. 389-96.

- ↑ David Rohl, Shoshenq, Shishak and Shysha, accessed 7 August 2009

- ↑ Grisanti, Michael A; Howard, Davd M. (1 April 2004). Giving the Sense. Kregel Academic & Professional. p. 193. ISBN 978-0-8254-2892-0.

- ↑ P. J. Furlong: Aspects of Ancient Near Eastern Chronology (c. 1600–700 BC), Gorgias Dissertations 46 (Gorgias Press, 2010), ISBN 978-1-60724-127-0, p. 16.

- ↑ Wilson, Kevin A. (2005). The Campaign of Pharaoh Shoshenq I into Palestine. Mohr Siebeck. p. 65. ISBN 3-16-148270-0.

- ↑ Kitchen, Kenneth A. (1973). The Third Intermediate Period in Egypt. Aris & Phillips. p. 432. ISBN 9780856680014.

- ↑ Noth, M. (1938). ZDPV 61. pp. 277–304.

- ↑ Albright, W. F. (1937–39). Archiv für Orientfoschung 12. pp. 385–86.

- ↑ Mazar, B. (1957). VTS 4. pp. 57–66.

- ↑ Aharoni, Y. (1966). The Land of the Bible. pp. 283–90.

- ↑ Burney, Charles Allen (2004). Historical dictionary of the Hittites. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-6564-8.

- ↑ The Lords of Avaris, Chapter 17.

- ↑ Newgrosh, pp. 54-86.

- ↑ Kitchen, Preface to the 2nd edition of TIPE.

- ↑ "ISIS - Journal of the Ancient Chronology Forum". newchronology.org.

- ↑ "ISIS - Journal of the Ancient Chronology Forum". newchronology.org.

- ↑ Rohl A Test of Time, Chapter 14, pp. 299-325

- ↑ Dever, William G. (1990) [1989]. "2. The Israelite Settlement in Canaan. New Archeological Models". Recent Archeological Discoveries and Biblical Research. USA: University of Washington Press. p. 47. ISBN 0-295-97261-0. Retrieved 2013-01-07.

(Of course, for some, that only made the Biblical story more miraculous than ever—Joshua destroyed a city that wasn't even there!)

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 M. Sturgis, It Ain’t Necessarily So: Investigating the Truth of the Biblical Past (Headlin, London, 2001), p. 7.

- ↑ The Lost Testament, pp. 16-29.

- ↑ The Lost Testament

- ↑ The Lost Testament, pp. 120-124.

- ↑ The Lost Testament, p. 318)

- ↑ Kitchen, Kenneth (2003). "Egyptian interventions in the Levant in Iron Age II". In Dever, William G. Symbiosis, symbolism, and the power of the past: Canaan, ancient Israel, and their neighbors from the Late Bronze Age through Roman Palaestina. Seymour Gitin. Eisenbrauns. pp. 113–132 [122]. ISBN 978-1-57506-081-1.

- ↑ Hornung, E. et al.: "Ancient Egyptian Chronology" (Handbook of Oriental Studies I, vol. 83, Brill, Leiden, 2006), p. 13.

- ↑ ISIS archive, Journal of the Ancient Chronology Forum.

- ↑ Sturt W. Manning in Classical Review, Vol. 47, No. 2 (1997), pp. 438-439, in a non-Egyptological context:

"Chronology and dating in academic archaeology and ancient history are subjects avidly practised by a few, regarded as a necessary but comprehensively boring evil by the majority. As with public transport, we all need the timetable in order to travel, but we have no desire to learn about the workings of the necessary trains, buses, tracks, roads, stations, connections, and so on. Moreover, the study of chronology is unpleasant, detailed, and difficult, and lacks intellectual status and élan. It is like engineering, or surgery. Thus, where possible, the academic establishment likes to find some study on chronology to be effectively definitive, and the agreed 'text': other, higher, work can then be attended to. E. Meyer's study of 1892 on Herodotos' chronology thus remains a basis for current study for Greek history; J. A. Brinkman's work on Kassite chronology (article 1970, book 1976) remains effectively definitive; and so on. It is only when some iconoclast, or outsider, challenges the whole structure, tries to 'beat the boffins', that general academic attention returns to chronology (e.g. Peter James et al., Centuries of Darkness, 1991, David Rohl, A Test of Time, 1995)."

- ↑ "In a special review issue of the Cambridge Archaeological Journal these proposals were roundly rejected by experts in all disciplines in Old World archaeology, a result virtually assured by the failure of the authors to present more than an outline restructuring for Egyptian chronology." Bennett (1996:2).

- ↑ Hornung, E. et al.: "Ancient Egyptian Chronology" (Handbook of Oriental Studies I, vol. 83, Brill, Leiden, 2006), p. 15.

- ↑ Christopher Bronk Ramsey et al., Radiocarbon-Based Chronology for Dynastic Egypt, Science Vol. 328. no. 5985 (18 June 2010), pp. 1554 - 1557.

- ↑ A Test of Time stayed in the top ten Sunday Times bestseller list for eight weeks in 1995 (from 17 September to 6 November, pp. 7-14).

- ↑ Berthoud, J-M. Creation Bible Et Science, 2008, ISBN 978-2-8251-3887-8, 244f.

- ↑ Alden Bass (2003), Which Came First, the Pyramids or the Flood?, Apologetics Press :: Reason & Revelation, November 2003 - 23[11]:97-101

- ↑ van der Land, J.G. (2000) "Pharaohs and the Bible: David Rohl's chronology untenable", Bijbel, Geschiedenis en Archeologie, December 1999

- ↑ van der Veen, P.G. (2000) "Is Rohl's Chronology inaccurate? A reply to BGA'," Bijbel, Geschiedenis en Archeologie, December 1999

- ↑ Porter, R.M. (2000) "'Did the Philistines settle in Canaan around 1200 BC?", Bijbel, Geschiedenis en Archeologie, December 1999

- ↑ van der Land, J.G. (2000), "Conclusive evidence against Rohl's proposed New Chronology: An Assyrian chancellor's archive", Bijbel, Geschiedenis en Archeologie, December 1999

- ↑ Newgrosh, B. "Chronology at the Crossroads: The Late Bronze Age in Western Asia" (Matador, ISBN 978-1-906221-62-1, Leicester, 2007)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to New Chronology (Rohl). |