New Age

The New Age movement is a religious or spiritual movement that developed in Western nations during the 1970s. Precise scholarly definitions of the movement differ in their emphasis, largely as a result of its highly eclectic structure. Nevertheless, the movement is characterised by a holistic view of the cosmos, a belief in an emergent Age of Aquarius – from which the movement gets its name – an emphasis on self-spirituality and the authority of the self, a focus on healing (particularly with alternative therapies), a belief in channeling, and an adoption of a "New Age science" that makes use of elements of the new physics.

The New Age movement evolved from an array of earlier religious movements and philosophies, in particular nineteenth-century groups such as the Theosophical Society and Gurdjieff. It also incorporates strands from metaphysics, perennial philosophy, self-help psychology, and various Indian teachings such as Buddhism, Hinduism and Yoga[1] In the 1970s, it developed a social and political component.[2] Its central precepts have been described as "drawing on both Eastern and Western spiritual and metaphysical traditions and infusing them with influences from self-help and motivational psychology".[3] The term New Age refers to the coming astrological Age of Aquarius.[4]

The New Age movement includes elements of older spiritual and religious traditions ranging from monotheism through pantheism, pandeism, panentheism, and polytheism combined with science and Gaia philosophy; particularly archaeoastronomy, astrology, ecology, environmentalism, the Gaia hypothesis, psychology, and physics. New Age practices and philosophies sometimes draw inspiration from major world religions: Buddhism, Taoism, Chinese folk religion, Christianity, Hinduism, Sufism (Islam), Judaism (especially Kabbalah), Sikhism; with strong influences from East Asian religions, Esotericism, Gnosticism, Hermeticism, Idealism, Neopaganism, New Thought, Spiritualism, Theosophy, Universalism, and Wisdom tradition.[5]

Definition

Religious studies scholar Paul Heelas characterised the New Age movement as "an eclectic hotch-potch of beliefs, practices and ways of life" which can be identified as a singular phenomenon through their use of "the same (or very similar) lingua franca to do with the human (and planetary) condition and how it can be transformed."[6] Similarly, historian of religion Olav Hammer termed it "a common denominator for a variety of quite divergent contemporary popular practices and beliefs" which have emerged since the late 1970s and which are "largely united by historical links, a shared discourse and an air de famille."[7] Sociologist of religion Michael York described the New Age movement as "an umbrella term that includes a great variety of groups and identities" but which are united by their "expectation of a major and universal change being primarily founded on the individual and collective development of human potential".[8] Adopting a different approach, religious studies scholar Wouter Hanegraaff asserted that "New Age" was "a label attached indiscriminately to whatever seems to fit it" and that as a result it "means very different things to different people."[9]

Many of those groups and individuals who could analytically be categorised as part of the New Age movement nevertheless reject the term "New Age" when in reference to themselves.[10] Thus, religious studies scholar James R. Lewis identified "New Age" as a problematic term, but asserted that "there exists no comparable term which covers all aspects of the movement" and that thus it remained a useful etic category for scholars to use.[11]

York described the New Age movement as a new religious movement (NRM).[12] Conversely, Heelas rejected this categorisation; he believed that while elements of the New Age movement represented NRMs, this was not applicable to every New Age group.[13] Hammer identified much of the New Age movement as corresponding to the concept of "folk religiosity" in that it seeks to deal with existential questions regarding subjects like death and disease in "an unsystematic fashion, often through a process of bricolage from already available narratives and rituals".[7] York also heuristically divides the New Age movement into three broad trends. The first, the "social camp", represents groups which primarily seek to bring about social change, while the second, "occult camp", instead focus on contact with spirit entities and channeling. York's third group, the "spiritual camp", represents a middle ground between these two camps, and which focuses largely on individual development.[14]

Terminology of the "New Age"

The term "new age", along with related terms like "new era" and "new world", long predate the emergence of the New Age movement, and have widely been used to assert that a better way of life for humanity is dawning.[15] It has, for instance, widely been used in political contexts; the Great Seal of the United States, designed in 1782, proclaims a "new order of ages", while in the 1980s the Soviet Premier Mikhail Gorbachev proclaimed that "all mankind is entering a new age".[15] It has also been widely used within various forms of Western esotericism. For instance, in 1809 William Blake described a coming era of spiritual and artistic advancement in his preface to Milton a Poem by stating: "... when the New Age is at leisure to pronounce, all will be set right ..."[16] In 1864 the American Swedenborgian Warren Felt Evans published The New Age and its Message, while in 1907 Alfred Orage and Holbrook Jackson began editing a weekly journal of Christian liberalism and socialism titled The New Age.[17]

History

Antecedents

The New Age movement is a form of Western esotericism,[18] and thus has antecedents stretching back to southern Europe in Late Antiquity.[19] As such, it has various antecedents within the esoteric milieu. Some of the New Age movement's constituent elements appeared initially in the 19th-century metaphysical movements: Spiritualism, Theosophy, and New Thought and also the alternative medicine movements of chiropractics and naturopathy.[4][20] The author Nevill Drury claimed there are "four key precursors of the New Age", who had set the way for many of its widely held precepts.[21]

One of the earliest influences on the New Age movement was the Swedish Christian mystic Emanuel Swedenborg (1688–1772), who professed the ability to communicate with angels, demons, and spirits.[22] Another early influence was the German physician and hypnotist Franz Mesmer (1734–1815), who claimed the existence of a force known as "animal magnetism" running through the human body.[22] A further major influence on the New Age movement was the Theosophical Society, an esoteric group co-founded by the Russian Helena Blavatsky (1831–1891). In her books Isis Unveiled (1877) and The Secret Doctrine (1888), Blavatsky claimed that her Society was conveying the essence of all world religions, and it thus emphasised a focus on comparative religion.[22]

A further influence was New Thought, which developed in late nineteenth century New England as a Christian-oriented healing movement before spreading throughout the United States.[23] An additional influence was George Gurdjieff (c. 1872–1949), who founded the philosophy of the Fourth Way, through which he conveyed a number of spiritual teachings to his disciples. A fifth individual whom Drury identified as an important influence upon the New Age movement was the Indian Swami Vivekananda (1863–1902), an adherent of the philosophy of Vedanta who first brought Hinduism to the West in the late 19th century.[24]

Popularisation behind these ideas has roots in the work of early 20th century writers such as D. H. Lawrence and William Butler Yeats. In the early- to mid-1900s, American mystic, theologian, and founder of the Association for Research and Enlightenment Edgar Cayce was a seminal influence on what later would be termed the New Age movement; he was known in particular for the practice some refer to as channeling.[25] Another prominent influence was the psychologist Carl Jung,[26] who was a proponent of the concept of the Age of Aquarius.[27][28][29] Former Theosophist Rudolf Steiner and his Anthroposophical movement are a major influence. Neo-Theosophist Alice Bailey published the book Discipleship in the New Age (1944), which used the term New Age in reference to the transition from the astrological age of Pisces to Aquarius.

Hanegraaff believed that the New Age movement's direct antecedents could be found in the UFO cults of the 1950s, which he termed a "proto-New Age movement". Many of these new religious movements had strong apocalyptic beliefs regarding a coming new age, which they typically asserted would be brought about by contact with extraterrestrials.[30]

From a historical perspective, the New Age movement is rooted in the counterculture of the 1960s.[31] This decade also witnessed the emergence of a variety of new religious movements and newly established religions in the United States, creating a spiritual milieu from which the New Age movement drew upon; these included the San Francisco Zen Center, Transcendental Meditation, Soka Gakkai, the Inner Peace Movement, the Church of All Worlds, and the Church of Satan.[32] Although there had been an established interest in Asian religious ideas in the U.S. from at least the eighteenth-century,[33] many of these new developments were variants of Hinduism, Buddhism, and Sufism which had been imported to the West from Asia following the U.S. government's decision to rescind the Asian Exclusion Act in 1965.[34] In 1962 the Esalen Institute was established in Big Sur, California.[35] It was from Esalen and other similar personal growth centers which had developed links to humanistic psychology that the human potential movement emerged, which would also come to exert a strong influence on the New Age movement.[36]

Meanwhile in Britain, a number of small religious groups that came to be identified as the "light" movement had begun declaring the existence of a coming new age, influenced strongly by the Theosophical ideas of Blavatsky and Bailey.[37] The most prominent of these groups was the Findhorn Foundation which founded the Findhorn Ecovillage in the Scottish area of Findhorn, Moray in 1962.[38]

All of these groups would create the backdrop from which the New Age movement emerged; as James R. Lewis and J. Gordon Melton point out, the New Age movement represents "a synthesis of many different preexisting movements and strands of thought".[39] Nevertheless, York asserted that while the New Age movement bore many similarities with both earlier forms of Western esotericism and Eastern religion, it remained "distinct from its predecessors in its own self-consciousness as a new way of thinking."[40]

Early development

The counterculture of the 1960s had rapidly declined by the start of the 1970s, in large part due to the collapse of the commune movement,[41] but it would be many former members of the counter-culture and hippy subculture who subsequently became early adherents of the New Age movement.[39] The exact origins of the New Age movement remain an issue of debate; Melton asserted that it emerged in the early 1970s,[42] whereas Hanegraaff instead traced its emergence to the latter 1970s, adding that it then entered its full development in the 1980s.[43] This early form of the movement was based largely in Britain and exhibited a strong influence from Theosophy and Anthroposophy.[44] Hanegraaff termed this early core of the movement the New Age sensu stricto, or "New Age in the strict sense".[44]

In the latter part of the 1970s, the New Age movement expanded to cover a wide variety of alternative spiritual and religious beliefs and practices, not all of which explicitly held to the belief in the Age of Aquarius, but which were nevertheless widely recognised as being broadly similar in their search for "alternatives" to mainstream society.[44] In doing so, the "New Age" became a banner under which to bring together the wider "cultic milieu" of American society.[18] Hanegraaff terms this development the New Age sensu lato, or "New Age in the wider sense".[44] This probably influenced several thousand small metaphysical book- and gift-stores that increasingly defined themselves as "New Age bookstores".[45][46]

1971 witnessed the foundation of est by Werner H. Erhard, a spiritual training course which became a prominent part of the early movement.[47] Melton suggested that the 1970s witnessed the growth of a relationship between the New Age movement and the older New Thought movement, as evidenced by the widespread use of Helen Schucman's A Course in Miracles (1975), New Age music, and crystal healing in New Thought churches.[48] Some figures in the New Thought movement were sceptical, challenging the compatibility of New Age and New Thought perspectives.[49]

Several key events occurred, which raised public awareness of the New Age subculture: the production of the musical Hair: The American Tribal Love-Rock Musical (1967) with its opening song "Aquarius" and its memorable line "This is the dawning of the Age of Aquarius";[50] publication of Linda Goodman's best-selling astrology books Sun Signs (1968) and Love Signs (1978); the release of Shirley MacLaine's book Out on a Limb (1983), later adapted into a television mini-series with the same name (1987); and the "Harmonic Convergence" planetary alignment on August 16 and 17, 1987,[51] organized by José Argüelles in Sedona, Arizona. The Convergence attracted more people to the movement than any other single event.[52]

The claims of channelers Jane Roberts (Seth Material), Helen Schucman (A Course in Miracles), J. Z. Knight (Ramtha), Neale Donald Walsch (Conversations with God) (note that Walsch denies being a "channeler" and his books make it obvious that he is not one, though the text emerged through a dialogue with a deeper part of himself in a process comparable to automatic writing), and Rene Gaudette (The Wonders) contributed to the movement's growth.[53][54] Relevant New Age works include the writings of James Redfield, Eckhart Tolle, Barbara Marx Hubbard, Christopher Hills, Marianne Williamson, Deepak Chopra, John Holland, Gary Zukav, Wayne Dyer, and Rhonda Byrne. The first significant exponent of the New Age movement in the U.S. has been cited as Ram Dass.[55] A core work in the movement was the 1975 publication A Course in Miracles.[56]

The Holistic aspect of the New Age movement moved into the mainstream with The Mandala Society's first Holistic Health Conferences that were ever presented along with a medical school. This was at the University of California, San Diego beginning in 1975 and continuing for ten years. Every year about 3,000 health professionals and educators participated in over thirty workshops focused on the many different aspects of Holistic Health. The first National Holistic Education Conference was presented with the University of California, San Diego, in 1979. These conferences were created and directed by David J. Harris who also created the National Center for the Exploration of Human Potential in 1968 for Dr. Herbert Otto and Dr. Abraham Maslow. The name was changed to The Health Optimizing Institute in 1992 and is one example of the Human Potential Movement's contribution to the New Age.

Beliefs and practices

Although there is great diversity among the beliefs and practices found within the New Age movement, according to York it is united by a shared "vision of radical mystical transformation on both the personal and collective levels".[57] The movement aims to create "a spirituality without borders or confining dogmas" that is inclusive and pluralistic.[21]

Theology, cosmology, and the Age of Aquarius

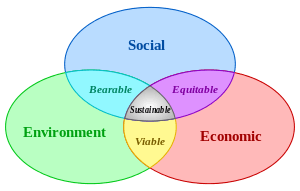

Most New Age groups subscribe to the view that there is an Ultimate Source from which all things originate; this source is often, although not always, referred to as God.[58] Various creation myths have been articulated in New Age publications outlining how this Ultimate Source came to create the universe and everything in it.[59] In contrast, some other New Agers have emphasised the idea of a universal inter-relatedness that is not always emanating from a single source.[60] The New Age worldview emphasises holism and the idea that everything in existence is intricately connected as part of a single whole,[61] in doing so rejecting both the dualism of Judeo-Christian thought and the reductionism of Cartesian science.[62] It emphasises that the Mind, Body, and Spirit are interrelated[4] and that there is a form of monism and unity throughout the universe.[20] It attempts to create "a worldview that includes both science and spirituality"[63]

The New Age movement typically views the material universe as a meaningful illusion, which humans should try to use constructively rather than focus on escaping into other spiritual realms.[64] This physical world is hence seen as "a domain for learning and growth" after which the human soul might pass on to higher levels of existence.[65] There is thus a widespread belief that reality is engaged in an ongoing process of evolution; rather than Darwinian evolution, this is typically seen as either a teleological evolution which assumes a process headed to a specific goal, or an open-ended, creative evolution.[66]

A common belief among the New Age movement is that humanity has entered, or is coming to enter, a new age known as the Age of Aquarius,[67] which Melton has characterised as a "New Age of love, joy, peace, abundance, and harmony[...] the Golden Age heretofore only dreamed about."[68] Prominent New Age theorist Marilyn Ferguson for instance describes this period as "a millennium of love and light".[69] In accepting this belief in a coming new age, the movement has been described as "highly positive, celebratory, [and] utopian",[70] and has also been cited as an apocalyptic movement.[71]

According to this world view, the planet goes through large astronomical cycles which can be identified astrologically; the prior two thousand years were described as the Age of Pisces, which is now giving way to that of Aquarius.[72] The Age of Aquarius is not viewed as eternal, but it is instead believed that it will last for around two thousand years, before being replaced by a further age.[72] There are various beliefs within the movement as to how this new age will come about, but most emphasise the idea that it will be established through human agency; others assert that it will be established with the aid of non-human forces such as spirits or extraterrastrials.[73] Participants in the movement typically express the view that their own spiritual actions are helping to bring about the Age of Aquarius.[74]

Self-spirituality and channeling

The New Age movement exhibits a strong emphasis on the idea that the individual is the primary source of authority on spiritual matters.[75] Thus, it exhibits what Heelas termed "unmediated individualism",[75] and reflects a world-view which is "radically democratic".[76] As a result, there is a strong emphasis on the freedom of the individual in the movement.[77] This emphasis has led to some ethical disagreements; while some New Age participants stress the need to help others because all are part of the unitary holistic universe, others have disagreed, refusing to aid others because it is believed that it will result in their dependency on others and thus conflicts with the self-as-authority ethic.[78] Nevertheless, within the movement, there are differences in the role accorded to voices of authority outside of the self.[79]

"In the flood of channeled material which has been published or delivered to "live" audiences in the last two decades, there is much indeed that is trivial, contradictory, and confusing. The authors of much of this material make claims which, while not necessarily untrue or fraudulent, are difficult or impossible for the reader to verify. There are, however, a number of other channeled documents which address issues more immediately relevant to the human condition. The best of these writings are not only coherant and plausible, but eloquently persuasive and sometimes disarmingly moving."

Although not present in every New Age group,[81] a core belief of the movement is in channeling.[82] This is the idea that humans beings, sometimes (although not always) in a state of trance, can act "as a channel of information from sources other than their normal selves".[83] These sources are varyingly described as being God, gods and goddesses, ascended masters, spirit guides, extraterrestrials, angels, devas, historical figures, the collective unconscious, elementals, or nature spirits.[83] Hanegraaff described channeling as a form of "articulated revelation",[84] and identified four forms: trance channeling, automatisms, clairaudient channeling, and open channeling.[85]

Prominent examples of channeling in the New Age movement include Jane Roberts' claims that she was contacted by an entity called Seth, and Helen Schucman's claims to have channeled Jesus Christ.[86] The academic Suzanne Riordan examined a variety of these New Age channeled messages, and noted that they typically "echoed each other in tone and content", offering an analysis of the human condition and giving instructions or advice for how humanity can discover its true destiny.[87]

For many New Agers, these channeled messages rival the scriptures of the main world religions as sources of spiritual authority,[88] although often New Agers describe historical religious revelations as forms of "channeling" as well, thus attempting to legitimate and authenticate their own contemporary practices.[89] Although the concept of channeling from discarnate spirit entities has links to Spiritualism and psychical research, in the New Age movement the Spiritualist emphasis on proving the existence of life after death is absent, as is the psychical research focus of testing mediums for consistency.[90]

Healing and alternative therapies

Another core factor of the New Age movement is its emphasis on healing and the use of alternative therapies.[91][92] The general ethos within the movement is that health is the natural state for the human being and that illness is a disruption of that natural balance.[93] Hence, New Age therapies seek to heal "illness" as a general concept which includes physical, mental, and spiritual aspects; in doing so it critiques mainstream Western medicine for simply attempting to cure disease, and thus has an affinity with most forms of traditional medicine found around the world.[94] The concept of "personal growth" is also greatly emphasised within the healing aspects of the New Age movement.[95] The movement's focus of self-spirituality has led to the emphasis of self-healing, although also present in the movement are ideas that focus on both healing others, and healing the Earth itself.[96]

The healing elements of the movement are difficult to classify given that a variety of terms are used, with some New Age authors using different terms to refer to the same trends, while others use the same term to refer to different things.[97] However, Hanegraaff developed a set of categories into which the forms of New Age healing could be roughly categorised. The first of these was the Human Potential Movement, which argues that contemporary Western society suppresses much human potential, and which accordingly professes to offer a path through which individuals can access those parts of themselves that they have alienated and suppressed, thus enabling them to reach their full potential and live a meaningful life.[98] Hanegraaff described transpersonal psychology as the "theoretical wing" of this Human Potential Movement; in contrast to other schools of psychological thought, transpersonal psychology takes religious and mystical experiences seriously by exploring the uses of altered states of consciousness.[99] Closely connected to this is the shamanic consciousness current, which argues that the shaman was a specialist in altered states of consciousness and which seeks to adopt and imitate traditional shamanic techniques as a form of personal healing and growth.[100]

Hanegraaff identified the second main healing current in the New Age movement as being holistic health. This emerged in the 1970s out of the free clinic movement of the 1960s, and has various connections with the Human Potential Movement.[101] It emphasises the idea tha the human individual is a holistic, interdependent relationship between mind, body, and spirit, and that healing is a process in which an individual becomes whole by integrating with the powers of the universe.[102] A very wide array of methods are utilised within the holistic health movement, with some of the most common including acupuncture, biofeedback, chiropractic, yoga, kinesiology, homeopathy, iridology, massage and other forms of bodywork, meditation and visualisation, nutritional therapy, psychic healing, herbal medicine, healing using crystals, metals, music, and colours, and reincarnation therapy.[103] The use of crystal healing has become a particularly prominent visual trope in the movement.[104] The mainstreaming of the Holistic Health movement in the UK is discussed by Maria Tighe. The inter-relation of holistic health with the New Age movement is illustrated in Jenny Butler's ethnographic description of "Angel therapy" in Ireland.[92]

"New Age science"

The New Age movement typically rejects rationalism, the scientific method, and the academic establishment, although at times employs terminology and concepts borrowed from science and particularly the New Physics.[105] Instead it typically expresses the view that its own understandings of the universe will come to replace those of the academic establishment in a paradigm shift.[105] A number of prominent influences on New Age movement, such as David Bohm and Ilya Prigogine, came from backgrounds as professional scientists.[106] Conversely, most of the academic and scientific establishments dismiss "New Age science" as pseudo-science, or at best existing in part on the fringes of genuine scientific research.[107] Hanegraaff identified "New Age science" as a form of Naturphilosophie.[108] In this, the movement is interested in developing unified world views to discover the nature of the divine and establish a scientific basis for religious belief.[106]

Figures in the New Age movement – most notably Fritjof Capra in his The Tao of Physics (1975) – have drawn parallels with theories in the New Physics and traditional forms of mysticism, thus arguing that contemporary science is proving ancient ideas.[109] Many New Agers have adopted James Lovelock's Gaia hypothesis that the Earth acts akin to a single living organism, although have expanded this idea to include the idea that the Earth has consciousness and intelligence.[110]

Quantum mechanics, parapsychology, and the Gaia hypothesis have been used in quantum mysticism to explain spiritual principles.[111] Authors Deepak Chopra, Fritjof Capra, Fred Alan Wolf, and Gary Zukav have linked quantum mechanics to New Age spirituality, which is presented in the film What the Bleep Do We Know!? (2004); also, in connection with the Law of Attraction, which is related to New Thought and presented in the film The Secret (2006). They have interpreted the Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle, quantum entanglement, wave function collapse, or the many-worlds interpretation to mean that all objects in the universe are one (monism), that possibility and existence are endless, and that the physical world is only what one believes it to be. In medicine, such practices as therapeutic touch, homeopathy, chiropractic, and naturopathy involve hypotheses and treatments that have not been accepted by the conventional, science-based medical community through the normal course of empirical testing.[112][113] New Age thought often includes references to the paranormal and to parapsychology.[114]

Philosophy and cosmology

| Concept | Description |

|---|---|

| Afterlife | New Age thinkers have expressed a variety of beliefs about an afterlife.[115] Every New Age person must find their own path — whether it involves reincarnation, non-existence, or a higher plane of consciousness. Some believe consciousness persists after death as life in different forms; the afterlife exists for further learning through the form of a spirit, reincarnation and/or near-death experiences. The New Age belief in reincarnation can differ from the Buddhist or Hindu concepts: seeing a soul, for example, born into a spiritual realm or even on a far-away planet, and there is no desire to end this process; there are also beliefs that either all individuals (not just a minority) can choose where they reincarnate, or that God/the universe always chooses the best reincarnation for each person.[116] |

| Eschatology | Related to the above; a belief that we are living on the threshold of a great change in human consciousness usually focused on the date December 21, 2012 when a major, usually positive, change was believed to have occurred.[117] See 2012 phenomenon. |

| Astrology | Horoscopes and the Zodiac are used in understanding, interpreting, and organizing information about personality, human affairs, and other terrestrial matters.[118] |

| Teleology | Life has a purpose; this includes a belief in synchronicity—that coincidences have spiritual meaning and lessons to teach those open to them. Everything is universally connected through God and participates in the same energy.[119] There is a cosmic goal and a belief that all entities are (knowingly or unknowingly) cooperating towards this goal. |

| Indigo children | Children are being born with a more highly developed spiritual power than earlier generations.[120][121] |

| Interpersonal relationships | New Age writer Mark Satin found that, even in the 1970s, New Age people were rejecting traditional sex roles in favor of relationships and ways of being that emphasized such qualities as authenticity, women's equality in all areas of life, and freedom to choose.[122] A pair of social scientists claims that New Agers are unusually committed to helping others, both in personal relationships (by drawing out people’s unique selves) and through volunteer activities.[123] New Age writers Corinne McLaughlin and David Spangler point to a longing for connectedness with other members of one's community.[124] A variety of possible New Age interpersonal and intra-community relationships, many highlighting the wisdom and empowerment of women, is explored in Starhawk's futuristic novel The Fifth Sacred Thing.[125] |

| Intuition | An important aspect of perception – offset by a somewhat strict rationalism – noted especially in the works of psychologist Carl Jung.[126] |

| Optimism | Positive thinking supported by affirmations will achieve success in anything,[127] based on the concept that Thought Creates. Therefore, as one begins focusing attention and consciousness on the positive, on the "half-filled" glass of water, reality starts shifting and materializing the positive intentions and aspects of life. A certain critical mass of people with a highly spiritual consciousness will bring about a sudden change in the whole population.[128] Humans have a responsibility to take part in positive creative activity and to work to heal ourselves, each other and the planet.[129] |

| Human Potential Movement | The human mind has much greater potential than that ascribed to it[130][131][132] and can even override physical reality.[133] |

| Spiritual healing | Humans have potential healing powers, such as therapeutic touch, which they can develop to heal others through touch or at a distance.[134] |

| Time | Concept of Eternal Now as a true nature of time (including the past, present, and a multitude of "snapshots" of the pre-constructed variants of the future). Cyclic, as well as relative nature of time. "Spirit sees things differently than you do. You work in a linear time frame and Spirit does not." A human's choices made in the present affect his/her linear past, as the totality of time is a closed dynamic system.[135][136] "You are eternal in both directions... If you look far enough into your past, you'll find your future there."[137] |

| Eclecticism | New Age spirituality is characterized by an individual approach to spiritual practices and philosophies, and the rejection of religious doctrine and dogma.[138] |

| Matriarchy | Feminine forms of spirituality, including feminine images of the divine, such as the female Aeon Sophia in Gnosticism, are deprecated by patriarchal religions.[20] |

| Ancient civilizations | Atlantis, Lemuria, Mu, and other lost lands existed.[139] Relics such as the crystal skulls and monuments such as Stonehenge and the Great Pyramid of Giza were left behind. |

| Diet | Food influences both the mind and body; it is generally preferable to practice vegetarianism, veganism and rawfoodism by eating fresh organic food, which is locally grown and in season;[140][141] fasting may be used.[142] |

Lifestyle

New Age spirituality has led to a wide array of literature on the subject and an active niche market, with books, music, crafts, and services in alternative medicine available at New Age stores, fairs, and festivals.

A number of New Age proponents have emphasised the use of spiritual techniques as a tool for attaining financial prosperity, thus moving the movement away from its counter-cultural origins.[143] Embracing this attitude, various books have been published espousing such an ethos, established New Age centres have held spiritual retreats and classes aimed specifically at business people, and New Age groups have developed specialised training for businesses.[144] These New Age corporate seminars originated with est, and were later popularised by such groups as Lifespring and Transformational Technologies, both of which promulgated New Age therapies within a broader secular image.[145] During the 1980s, many prominent U.S. corporations, among them IBM, AT&T, and General Motors, embraced these seminars, hoping that they could increase productivity and efficiency among their work force.[146] Problematically, in several cases this resulted in employees bringing legal action against their employers for infringing on their religious beliefs or damaging their psychological health.[147] However, the use of spiritual techniques as a method for attaining profit has been an issue of major dispute within the wider New Age movement.[148] In particular, the movement's commercial elements have caused problems given that they often conflict with its general economically-egalitarian ethos; as York highlighted, "a tension exists in New Age between socialistic egalitarianism and capitalistic private enterprise".[149]

Demographics

People who practice New Age spirituality or who embrace its lifestyle are included in the Lifestyle of Health and Sustainability (LOHAS) demographic market segment, figures rising, related to sustainable living, green ecological initiatives, and generally composed of a relatively affluent and well-educated segment.[150][151] The LOHAS market segment in 2006 was estimated at USD$300 billion, approximately 30 percent of the United States consumer market.[152][153] According to The New York Times, a study by the Natural Marketing Institute showed that in 2000, 68 million Americans were included within the LOHAS demographic. The sociologist Paul H. Ray, who coined the term cultural creatives in his book The Cultural Creatives: How 50 Million People Are Changing the World (2000), states, "What you're seeing is a demand for products of equal quality that are also virtuous."[154][155]

The movement is strongly gendered; sociologist Ciara O'Connor argues that it shows a tension between commodification and women's empowerment.[156]

In the mid-1990s, it was asserted that the New Age movement was primarily found in the United States and Canada, Western Europe, and Australia and New Zealand.[157] It is problematic ascertaining the number of New Agers because many individuals involved in the movement don't explicitly identify themselves as such.[11] Heelas highlighted the range of attempts to establish the number of New Age participants in the U.S. during this period, noting that estimates ranged from 20,000 to 6 million; he believed that the higher ranges of these estimates were greatly inflated by, for instance, an erroneous assumption that all Americans who believed in reincarnation were parts of the movement.[158] He nevertheless suggested that over 10 million people in the U.S. had had some contact with New Age practices or ideas.[159]

Susan Lee Brown noted that in the U.S., the movement was first embraced by the baby boomer generation (those born between 1946 and 1964), "through which it was incubated and transmitted to other parts of American society".[160] Heelas asserted that the movement was "strongly associated" with members of the middle and upper-middle classes of Western society.[161] He added that within that broad demographic, the movement had nevertheless attracted a diverse clientele.[162] He typified the typical New Ager as someone who was well-educated yet disenchanted with mainstream society, thus arguing that the movement catered for those who believe that modernity is in crisis.[163] He suggested that the movement appealed to many former practitioners of the 1960s counter-culture because while they came to feel that they were unable to change society, they were nonetheless interested in changing the self.[164]

He highlighted that those involved in the movement did so to varying degrees.[165] Heelas argued that those involved in the movement could be divided into three broad groups; the first comprised those who were completely dedicated to it and its ideals, often working in professions that furthered those goals. The second consisted of "serious part-timers" who worked in unrelated fields but who nevertheless spent much of their free time involved in movement activities. The third was that of "casual part-timers" who occasionally involved themselves in New Age activities but for whom the movement was not a central aspect of their life.[166]

Community

Some New Agers advocate living in a simple and sustainable manner to reduce humanity's impact on the natural resources of Earth; and they shun consumerism.[168][169][170] The New Age movement has been centered around rebuilding a sense of community to counter social disintegration; this has been attempted through the formation of intentional communities, where individuals come together to live and work in a communal lifestyle.[171]

New Age centres have been set up in various parts of the world, representing an institutionalised form of the movement.[172] Notable examples include the Naropa Institute in Boulder, Colorado, Holly Hock Farm near to Vancouver, the Wrekin Trust in West Malvern, Worcestershire, and the Skyros Centre in Skyros.[173]

Criticising mainstream Western education as counterproductive to the ethos of the movement, many New Age groups have established their own schools for the education of children, although in other case such groups have sought to introduce New Age spiritual techniques into pre-existing establishments.[174]

Music

New-age music is peaceful music of various styles intended to create inspiration, relaxation, and positive feelings while listening. Studies have determined that new-age music can be an effective component of stress management.[175]

The style began in the 1970s with the works of free-form jazz groups recording on the ECM label; such as Oregon, the Paul Winter Consort, and other pre-ambient bands; as well as ambient music performer Brian Eno and classical avant-garde musician Daniel Kobialka.[176][177] In the early 1970s, it was mostly instrumental with both acoustic and electronic styles. New-age music evolved to include a wide range of styles from electronic space music using synthesizers and acoustic instrumentals using Native American flutes and drums, singing bowls, and world music sounds to spiritual chanting from other cultures.[176][177]

Many online radio stations exemplify new-age, which has always been a non-empirical phenomenon-intuitive-ethereal genre. For example, Gaia Radio

Reception

Academia

The earliest academic studies of the New Age movement were performed by specialists in the study of new religious movements, such as Robert Ellwood.[178] However, this research was often scanty because many scholars of alternative spirituality thought of the New Age movement as an insignificant cultural fad.[179] Alternately, much of it was largely negative and critical of New Age groups, as it was influenced by the U.S. anti-cult movement.[180] In 1996, Wouter Hanegraaff published New Age Religion and Western Culture, a historical analysis of New Age texts.[181] That same year, Paul Heelas published a study of the movement which focused on its manifestation in Britain.[182]

While J. Gordon Melton,[183] Wouter Hanegraaff,[184] and Paul Heelas[185] have emphasised personal aspects, Mark Satin,[186] Theodore Roszak,[187] Marilyn Ferguson,[188] and Corinne McLaughlin[189] have described New Age as a values-based sociopolitical movement.

In the 2003 book A Culture of Conspiracy: Apocalyptic Visions in Contemporary America written by Michael Barkun, professor emeritus of political science at the Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs[190] Barkun argues New Age beliefs have been greatly facilitated by the advent of the internet which has exposed people to beliefs once consigned to the outermost fringe of political and religious life. He identifies two trends which he terms, " the rise of improvisational millennialism" and "the popularity of stigmatized knowledge". He voices concern that these trends could lead to mass hysteria and could have a devastating effect on American political life.

Christian perspectives

In the United States, the New Age movement became a major concern of evangelical Christian groups in the 1980s, an attitude that gradually also influenced British evangelical groups.[191] During that decade, evangelical writers such as Constance Cumbey, Dave Hunt, Gary North, and Douglas Groothuis published books criticising the New Age movement from their Christian perspective; a number of them have been characterised as propagating conspiracy theories regarding the origin and purpose of the movement.[192] The most successful such publication however was Frank E. Peretti's 1986 novel This Present Darkness, which sold over a million copies; it depicted the New Age movement as being in league with feminism and secular education to overthrow Christianity.[193] This criticism has been sustained since; in 2003 Richard Land of the Southern Baptist Convention stated that there's "widespread agreement" by Baptists who regard New Age ideas as contrary to Christian tradition and doctrine.[194]

The Roman Catholic Church published A Christian reflection on the New Age in 2003, following a six-year study; the 90-page document criticizes New Age practices such as yoga, meditation, feng shui, and crystal healing.[195][196] According to the Vatican, euphoric states attained through New Age practices should not be confused with prayer or viewed as signs of God's presence.[197] Cardinal Paul Poupard, then-president of the Pontifical Council for Culture, said the "New Age is a misleading answer to the oldest hopes of man".[195] Monsignor Michael Fitzgerald, then-president of the Pontifical Council for Interreligious Dialogue, stated at the Vatican conference on the document: the "Church avoids any concept that is close to those of the New Age".[198]

Contemporary Pagan perspectives

An issue of academic debate has been regarding the connection between the New Age movement and contemporary Paganism, or Neo-Paganism. Sarah Pike asserted that that there was a "significant overlap" between the two religious movements,[199] while Aidan A. Kelly stated that Paganism "parallels the New Age movement in some ways, differs sharply from it in others, and overlaps it in some minor ways."[200] Hanegraaff suggested that whereas various forms of contemporary Paganism were not part of the New Age movement – particularly those who pre-dated the movement – other Pagan religions and practices could be identified as New Age.[201] Various differences between the two movements have been highlighted; the New Age movement focuses on an improved future, whereas the focus of Paganism is on the pre-Christian past.[202] Similarly, the New Age movement typically propounds a universalist message which sees all religions as fundamentally the same, whereas Paganism stresses the difference between monotheistic religions and those embracing a polytheistic or animistic theology.[202] Further, the New Age movement shows little interest in magic and witchcraft, which are conversely core interests of many Pagan religions, such as Wicca.[202]

Many Pagans have expressed criticism of the high fees charged by New Age teachers, something not typically present in the Pagan movement.[203] Followers of the Goddess movement have severely criticized the New Age as fundamentally patriarchal, analytical rather than intuitive, and as supporting the status quo, particularly in its implicit gender roles. Monica Sjöö (1938–2005) wrote that New Age channelers were virtually all women, but the spirits they purported to channel, offering guidance to humanity, were nearly all male. Sjöö was highly critical of Theosophy, the "I AM" Activity, and particularly Alice Bailey, whom she saw as promoting Nazi-like Aryan ideals. Sjöö's writings also condemn the New Age for its support of communication and information processing technologies which, she believes, may produce harmful low-level electromagnetic radiation.[204][205][206]

Integral theory

The author Ken Wilber posits that most New Age thought falls into what he termed the pre/trans fallacy.[207] According to Wilber, human developmental psychology moves from the pre-personal, through the personal, then to the transpersonal (spiritually advanced or enlightened) level.[208] He regards 80 percent of New Age spirituality as pre-rational (pre-conventional) and as relying primarily on mythic-magical thinking; this contrasts with a post-rational (including and transcending rational) genuinely world-centric consciousness.[207][208] Despite his criticism of most New Age thought, Wilber has been categorized as New Age due to his emphasis on a transpersonal view,[209] and more recently, as a philosopher.[210]

Native American

Indigenous American spiritual leaders, such as Elders councils of the Lakota, Cheyenne, Navajo, Creek, Hopi, Chippewa and Haudenosaunee have denounced New Age misappropriation of their sacred ceremonies[211] and other intellectual property,[212] stating that "The value of these instructions and ceremonies [when led by unauthorized people] are questionable, maybe meaningless, and hurtful to the individual carrying false messages."[211] Traditional leaders of the Lakota, Dakota, and Nakota peoples have reached consensus[213][214] to reject "the expropriation of [their] ceremonial ways by non-Indians". They see the New Age movement as either not fully understanding, deliberately trivializing, or distorting their way of life,[215] and have declared war on all such "plastic medicine people" who are appropriating their spiritual ways.[213][214] The United Nations General Assembly has issued a declaration protecting ceremonies as part of the cultural and intellectual property of their respective Indigenous nations:

Article 31 1. "Indigenous peoples have the right to maintain, control, protect and develop their cultural heritage, traditional knowledge and traditional cultural expressions, as well as the manifestations of their sciences, technologies and cultures, including human and genetic resources, seeds, medicines, knowledge of the properties of fauna and flora, oral traditions, literatures, designs, sports and traditional games and visual and performing arts. They also have the right to maintain, control, protect and develop their intellectual property over such cultural heritage, traditional knowledge, and traditional cultural expressions." - Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples[212]

Indigenous leaders have spoken out against individuals from within their own communities who may go out into the world to become a "white man's shaman," and any "who are prostituting our spiritual ways for their own selfish gain, with no regard for the spiritual well-being of the people as a whole".[215] The term "plastic shaman" or "plastic medicine people" has been applied to outsiders who identify themselves as shamans, holy people, or other traditional spiritual leaders, but who have no genuine connection to the traditions or cultures they claim to represent.[216][217][218]

The academic Ward Churchill criticized the New Age movement as an instrument of cultural imperialism that is exploitative of indigenous cultures by reducing them to a commodity to be traded. In Fantasies of the Master Race, he criticized the cultural appropriation of Native American culture and symbols in not only the New Age movement, but also in art and popular culture.[219]

Social and political movement

While many commentators have focused on the personal aspects of the New Age movement, it also has a social and political component. The New Age political movement became visible in the 1970s, peaked in the 1980s, and continued into the 1990s.[220] In the 21st century, the political movement evolved in new directions.

Late 20th century

After the political turmoil of the 1960s, many activists in North America and Europe became disillusioned with traditional reformist and revolutionary political ideologies.[221] Some began searching for a new politics that gave special weight to such topics as consciousness, ecology, personal and spiritual development, community empowerment, and global unity.[222][223] An outpouring of books from New Age thinkers acknowledged that search and attempted to articulate that politics.

According to some observers,[224][225] the first was Mark Satin's New Age Politics (1978).[186] It originally appeared in Canada in 1976.[226][227] Other books that have been described as New Age political include Theodore Roszak's Person / Planet (1978),[187][228] Marilyn Ferguson's The Aquarian Conspiracy (1980),[188][220] Alvin Toffler and Heidi Toffler's The Third Wave (1980),[220][229] Hazel Henderson's The Politics of the Solar Age (1981),[220][230] Fritjof Capra's The Turning Point (1982),[220][231] Robert Muller's New Genesis (1982),[232][233] John Naisbitt's Megatrends (1982),[233][234] Willis Harman's Global Mind Change (1988),[2][235] James Redfield's The Celestine Prophecy (1993),[2][236] and Corinne McLaughlin and Gordon Davidson's Spiritual Politics (1994).[2][189]

All these books were issued by major publishers. Some became international bestsellers. By the 1980s, New Age political ideas were being discussed in big-city newspapers[237][238] and established political magazines.[225][239] In addition, some of the New Age's own periodicals were regularly addressing social and political issues. In the U.S., observers pointed to Leading Edge Bulletin,[233][240] New Age Journal,[241][242] New Options Newsletter,[233][243] and Utne Reader.[241][244] Other such periodicals included New Humanity (England),[245] Alterna (Denmark),[246] Odyssey (South Africa), and World Union from the Sri Aurobindo Ashram (India).

As with any political movement, organizations sprang up to generate popular support for New Age political ideas and policy positions. In the U.S., commentators identified the New Age Caucus of California,[247][248] the New World Alliance,[249][250] Planetary Citizens,[233][251] and John Vasconcellos's Self-Determination: A Personal / Political Network[233][252] as New Age political organizations. So, on occasion, did their own spokespeople.[253] There may have been more New Age political organizing outside the U.S.;[251] writer-activists pointed to the Future in Our Hands movement in Norway (which claimed 20,000 adherents out of a population of four million),[254] the early European Green movements,[255] and the Values Party of New Zealand.[256]

Although these books, periodicals, and organizations did not speak with one voice, commentators found that many of them sounded common themes:

- Our world does not reflect who we at our best can be.[225]

- All our most significant social and political problems go back at least 300 years.[257]

- The political system therefore needs to be transformed, not just reformed,[220] with the help of a new political theory appropriate to our time.[221]

- Holism – seeing everything as connected – is the first step on the way to creating that new political theory.[220][225]

- Doing away with the categories of "left" and "right" is another essential part of that task.[220][225]

- Significant social change requires deep changes in consciousness; institutional change is not enough.[221][258]

- Above all, consciousness needs to become more ecologically aware,[225][233] more feminist,[225][233] and more oriented to compassionate global unity.[220][233]

- Desirable values include nonviolence, diversity, a sense of community, and a sense of enoughness.[233][239]

- Human growth and development, not economic growth, should be the overarching goal of New Age society.[239]

- Ownership and control of institutions is important. But the size of institutions is at least as important. We must move away from big governments, big corporations, and other large institutions to the extent it enhances our lives.[220][239]

- We can begin this process by interlacing hierarchical structures with horizontal networks.[233][259]

- Global unification is a key goal, but is probably best accomplished by networking at many levels rather than establishing a centralized world state.[220]

- The agent of political change is no longer the working class, or any economic class. Instead, it is all those who are developing themselves personally and spiritually – all who aspire to live lives of dignity and service.[221]

- Evolution is to be preferred to revolution. However, the forces of evolutionary change need not be a statistical majority. A "critical mass" of informed, committed, and spiritually aware people can move a nation forward.[220][249]

Over time, these themes began to cohere. By the 1980s, observers in both North America[225][258] and Europe[260][261] were acknowledging the emergence of a New Age political "ideology".

Political objections at century’s end

Toward the end of the 20th century, criticisms were being directed at the New Age political project from many quarters,[262][263] but especially from the liberal left and religious right.

On the left, scholars argued that New Age politics is an oxymoron: that personal growth has little or nothing to do with political change.[264][265] One political scientist said New Age politics fails to recognize the "realities" of economic and political power;[258] another faulted it for not being opposed to the capitalist system, or to liberal individualism.[221] Antinuclear activist Harvey Wasserman argued that New Age politics is too averse to social conflict to be effective politically.[225]

On the right, some worried that the drive to come up with a new consciousness and new values would topple time-tested old values.[251] Others worried that the celebration of diversity would leave no strong viewpoint in place to guide society.[251] The passion for world unity – one humanity, one planet – was said to lead inevitably to the centralization of power.[266][267] Some doubted that networking could provide an effective counterweight to centralization and bureaucracy.[233]

Neither left nor right was impressed with the New Age's ability to organize itself politically.[225][249] Many explanations were offered for the New Age's practical political weakness. Some said that the New Age political thinkers and activists of the 1970s and 1980s were simply too far in advance of their time.[268] Others suggested that New Age activists' commitment to the often frustrating process of consensus decision-making was at fault.[249] After it dissolved, New World Alliance co-founder Marc Sarkady told an interviewer that the Alliance had been too "New Age counter-cultural" to appeal to a broad public.[269]

New political directions in the 21st century

In the 21st century, writers and activists continue to pursue a political project with New Age roots. However, it differs from the project that had come before.

The principal difference was anticipated in texts like New Age Politics author Mark Satin's essay "Twenty-eight Ways of Looking at Terrorism" (1991),[270] human potential movement historian Walter Truett Anderson's essay "Four Different Ways to Be Absolutely Right" (1995),[271] and mediator Mark Gerzon's book A House Divided (1996).[272][273] In these texts, the New Age political perspective is recognized as legitimate. But it is presented as merely one among many, with strong points and blind spots just like all the rest. The result was to alter the nature of the New Age political project. If every political perspective had unique strengths and significant weaknesses, then it no longer made sense to try to convert everyone to the New Age political perspective, as had been attempted in the 1970s and 1980s. It made more sense to try to construct a higher political synthesis that took every political perspective into account, including that of the New Age.[274][275]

Many 21st century books have attempted to articulate foundational aspects of this approach to politics and social change. They include Ken Wilber's A Theory of Everything (2001),[276] Mark Satin's Radical Middle (2004),[277] David Korten's The Great Turning (2006),[278] Steve McIntosh's Integral Consciousness and the Future of Evolution (2007),[279] Marilyn Hamilton's Integral City (2008),[280] and Carter Phipps's Evolutionaries (2012).[281] In addition, many organizations are providing opportunities for focused political listening and learning that can contribute to the construction of a higher political synthesis. They include AmericaSpeaks,[282] Association Reset-Dialogues on Civilizations,[283] Listening Project,[284] Search for Common Ground,[285] Spiral Dynamics Integral,[286][287] and World Public Forum: Dialogue of Civilizations.[288]

Another difference between the two eras of political thought is that, in the 21st century, few political actors use the term New Age or post-New Age[289] to describe themselves or their work. Some observers attribute this to the negative connotations that the term "New Age" had acquired.[223][289] Instead, other terms are employed that connote a similar sense of personal and political development proceeding together over time. For example, according to an anthology from three political scientists, many writers and academics use the term "transformational" as a substitute for such terms as New Age and new paradigm.[257] Ken Wilber has popularized use of the term "integral",[276] Carter Phipps emphasizes the term "evolutionary",[281] and both terms can be found in some authors' book titles.[279][280]

See also

- 2012 phenomenon

- Biofeedback

- Cybersectarianism

- Eco-communalism

- Higher consciousness

- Hippies

- Holotropic breathing

- Hypnosis

- Mantras

- Neuro-linguistic programming

- New Age communities

- New religious movement

- Paradigm shift

- Peace movement

- Philosophy of happiness

- Rebirth

- Social conditioning

- Social equality

- Spiritual evolution

- Transpersonal psychology

- Woodstock

Notes

- ↑ Drury 2004, pp. 8–10

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Mayne, Alan J. (1999). From Politics Past to Politics Future: An Integrated Analysis of Current and Emergent Paradigms. Praeger Publishers / Greenwood Publishing Group, pp. 167–68 and 177–80. ISBN 978-0-275-96151-0.

- ↑ Drury 2004, p. 12

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Melton, J. Gordon – Director Institute for the Study of American Religion. New Age Transformed, retrieved 2006-06

- ↑ Lewis 1992, pp. 15–18

- ↑ Heelas 1996, pp. 1–2.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Hammer 2006, p. 855.

- ↑ York 1995, pp. 1–2.

- ↑ Hanegraaff 1996, p. 1.

- ↑ Lewis 1992, pp. 1–2; Heelas 1996, p. 17.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Lewis 1992, p. 2.

- ↑ York 1995, p. 2.

- ↑ Heelas 1996, p. 9.

- ↑ York 1995, pp. 36–37.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Heelas 1996, p. 15.

- ↑ Blake, William; Sampson, John (2006), "Selections from Milton", in John Sampson, The Poetical Works of William Blake: Including the Unpublished French Revolution; Together with the Minor Prophetic Books and Selections from the Four Zoas, Milton and Jerusalem, Whitefish, Montana, US: Kessinger Publishing, p. 369, ISBN 978-1-4286-1155-9, retrieved 2010-10-05

- ↑ Heelas 1996, p. 17.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 York 1995, p. 33.

- ↑ Ellwood 1992, p. 59.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 Michael D. Langone, Ph.D. Cult Observer, 1993, Volume 10, No. 1. What Is "New Age"?, retrieved 2006-07

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Drury 2004, p. 8.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 Alexander 1992, p. 31.

- ↑ Alexander 1992, p. 35.

- ↑ Drury 2004, pp. 27–28

- ↑ York 1995, p. 60.

- ↑ Heelas 1996, pp. 46–47.

- ↑ Stein, Murray (2005), Transformation, Texas A & M University Press, p. 138, ISBN 978-1-58544-449-6

- ↑ Letters of C. G. Jung: Volume I, 1906–1950, p. 285

- ↑ Dunne, Claire (2000), "Visions", Carl Jung: Wounded Healer of the Soul: An Illustrated Biography (Illustrated (2003) ed.), London, UK: Continuum International Publishing Group, p. 126, ISBN 978-0-8264-6307-4, retrieved 2010-10-04

- ↑ Hanegraaff 1996, pp. 95–96.

- ↑ Hanegraaff 1996, p. 11.

- ↑ Heelas 1996, pp. 53–54.

- ↑ Brown 1992, pp. 88–89.

- ↑ Melton 1992, p. 20; Heelas 1996, pp. 54–55.

- ↑ Alexander 1992, pp. 36–37; York 1995, p. 35; Hanegraaff 1996, pp. 38–39; Heelas 1996, p. 51.

- ↑ Alexander 1992, pp. 36, 41–43; York 1995, p. 8; Heelas 1996, p. 53.

- ↑ Melton 1992, p. 20.

- ↑ Melton 1992, p. 20; York 1995, p. 35; Hanegraaff 1996, pp. 38–39; Heelas 1996, p. 51.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 Lewis & Melton 1992, p. xi.

- ↑ York 1995, p. 1.

- ↑ Heelas 1996, p. 54.

- ↑ Melton 1992, p. 18.

- ↑ Hanegraaff 1996, p. 12.

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 44.2 44.3 Hanegraaff 1996, p. 97.

- ↑ Algeo, John; Algeo, Adele S. (1991), Fifty Years Among the New Words: A Dictionary of Neologisms, 1941–1991, Cambridge University Press, p. 234, ISBN 978-0-521-44971-7

- ↑ Materer, Timothy (1995), Modernist Alchemy: Poetry and the Occult, Cornell University Press, p. 14, ISBN 978-0-8014-3146-3

- ↑ Heelas 1996, pp. 58–60.

- ↑ Melton 1992, pp. 25–26.

- ↑ Melton 1992, pp. 26–27.

- ↑ Hanegraaff 1996, pp. 10–11

- ↑ Hanegraaff 1996, p. 335

- ↑ Lewis & Melton 1992, p. ix.

- ↑ Lewis 1992, pp. 22–23

- ↑ Drury 2004, pp. 133–34

- ↑ York 1995, p. 35.

- ↑ York 1995, pp. 35–36.

- ↑ York 1995, p. 39.

- ↑ Hanegraaff 1996, p. 120.

- ↑ Hanegraaff 1996, pp. 122–123.

- ↑ Hanegraaff 1996, p. 128.

- ↑ Hanegraaff 1996, p. 119; Drury 2004, p. 11.

- ↑ Hanegraaff 1996, p. 119.

- ↑ Drury 2004, p. 10

- ↑ Hanegraaff 1996, p. 115.

- ↑ Hanegraaff 1996, pp. 116–117.

- ↑ Hanegraaff 1996, pp. 158–160.

- ↑ Hanegraaff 1996, p. 94.

- ↑ Melton 1992, p. 19.

- ↑ Ferguson, The Aquarian Conspiracy (1980), p. 19.

- ↑ Heelas 1996, p. 28.

- ↑ Melton 1992, p. 24.

- ↑ 72.0 72.1 Hanegraaff 1996, p. 102.

- ↑ Heelas 1996, p. 74.

- ↑ Melton 1992, p. 19; Heelas 1996, pp. 75–76.

- ↑ 75.0 75.1 Heelas 1996, pp. 21–23.

- ↑ Riordan 1992, p. 124.

- ↑ Heelas 1996, pp. 26–27.

- ↑ Heelas 1996, p. 25.

- ↑ Heelas 1996, p. 34.

- ↑ Riordan 1992, p. 107.

- ↑ Riordan 1992, p. 105.

- ↑ Melton 1992, p. 21; Hanegraaff 1996, p. 23.

- ↑ 83.0 83.1 Hanegraaff 1996, pp. 23–24.

- ↑ Hanegraaff 1996, p. 24.

- ↑ Hanegraaff 1996, pp. 27–28.

- ↑ Melton 1992, p. 22; Riordan 1992, pp. 108–110.

- ↑ Riordan 1992, p. 110.

- ↑ Riordan 1992, p. 108.

- ↑ Hanegraaff 1996, pp. 26–27.

- ↑ Melton 1992, p. 23.

- ↑ Ellwood 1992, p. 60; York 1995, p. 37; Hanegraaff 1996, p. 42.

- ↑ 92.0 92.1 Butler, Jenny and Maria Tighe, "Holistic Health and New Age in the British Isles". 415-34 in Kemp, Daren and Lewis, James R., ed. (2007), Handbook of New Age, Boston, Massachusetts, US: Brill Academic Publishers, ISBN 978-90-04-15355-4.

- ↑ Hanegraaff 1996, pp. 46–47.

- ↑ Albanese 1992, pp. 81–82; Hanegraaff 1996, pp. 42–43.

- ↑ Hanegraaff 1996, p. 46.

- ↑ Heelas 1996, pp. 82–87.

- ↑ Hanegraaff 1996, p. 48.

- ↑ Hanegraaff 1996, pp. 48–49.

- ↑ Hanegraaff 1996, pp. 50–51.

- ↑ Hanegraaff 1996, p. 52.

- ↑ Hanegraaff 1996, pp. 53–54.

- ↑ Hanegraaff 1996, p. 54.

- ↑ York 1995, p. 37; Hanegraaff 1996, pp. 54–55.

- ↑ Albanese 1992, p. 79.

- ↑ 105.0 105.1 Heelas 1996, p. 5; Hanegraaff 1996, p. 62.

- ↑ 106.0 106.1 Hanegraaff 1996, p. 63.

- ↑ Hanegraaff 1996, p. 62.

- ↑ Hanegraaff 1996, p. 64.

- ↑ Hanegraaff 1996, pp. 128–129.

- ↑ Hanegraaff 1996, pp. 155–156; Heelas 1996, p. 86.

- ↑ Quantum Interconnectedness, retrieved 2007-08-23

- ↑ Shine, KI (2001), "A critique on complementary and alternative medicine", Journal of Alternative Complementary Medicine, 7 Suppl 1: S145–52, doi:10.1089/107555301753393922, PMID 11822630

- ↑ Singh, Simon; Edzard Ernst (2008), Trick or Treatment, The Undeniable Facts about Alternative Medicine, Norton, ISBN 978-0-393-06661-6

- ↑ Hess, David J. (1993). Science in the New Age: The Paranormal, Its Defenders and Debunkers, and American Culture. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 978-0-299-13824-0.

- ↑ Drury, Nevill (1999). Exploring the Labyrinth: Making Sense of the New Spirituality. Continuum Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8264-1182-2.

- ↑ New Age Afterlife and Salvation, Patheos online library

- ↑ Sacha Defesche (2007). "'The 2012 Phenomenon': A historical and typological approach to a modern apocalyptic mythology.". skepsis. Retrieved April 29, 2011.

- ↑ Lewis 1992, pp. 187–88

- ↑ Only God Exists, archived from the original on 2006-08-04, retrieved 2006-07-01

- ↑ CNN News transcript of interview with Sandy Bershad, an Indigo Child, Cable News Network, 2005-11-15, retrieved 2009-06-09

- ↑ "Indigo Children – Crystalline Children", Awakening-Healing News, 2002-06-04, ISBN 978-1-56414-948-0, retrieved 2006-10-01

- ↑ Satin (1978), cited above, pp. 25-27 and 111-12.

- ↑ Ray, Paul H.; Anderson, Sherry Ruth (2000). The Cultural Creatives: How 50 Million People Are Changing the World. Random House, pp. xiv and 29. ISBN 978-0-609-60467-0.

- ↑ McLaughlin, Corinne; Davidson, Gordon (1985). Builders of the Dawn: Community Lifestyles in a Changing World. Stillpoint Publishing, pp. 9-11 (Spangler is quoted). ISBN 978-0-913299-20-3.

- ↑ Starhawk (1993). The Fifth Sacred Thing. Bantam Books. ISBN 978-0-553-37380-6.

- ↑ Hanegraaff 1996, pp. 217–24

- ↑ The Salem New Age Center. Salem, Massachusetts, US. Supercharged Affirmations, retrieved 2007-08

- ↑ Carroll, Robert Todd (2005), "The Hundredth Monkey Phenomenon", Skeptic's Dictionary, retrieved 2007-08-23

- ↑ Accepting Total and Complete Responsibility: New Age NeoFeminist Violence against Sethna Feminism Psychology. (1992) 2: pp. 113–19

- ↑ Clarke, Peter Bernard (2006), New Religions in Global Perspective: A Study of Religious Change in the Modern World, Routledge, pp. 31–32, ISBN 978-0-415-25747-3

- ↑ Hanegraaff 1996, pp. 203–55

- ↑ Hunt, Stephen (2003), Alternative Religions: A Sociological Introduction, Ashgate Publishing, pp. 5–6, ISBN 978-0-7546-3410-2

- ↑ Reality Shifters news

- ↑ Lewis 1992, p. 14

- ↑ Letters from home : loving messages from the family. by Kryon, (Spirit); Lee Carroll. ISBN 978-1-888053-12-8

- ↑ Тhe end times : new information for personal peace : Kryon book 1. Lee Carroll; Kryon, (Spirit). ISBN 978-0-9636304-2-1

- ↑ 2000: passing the marker (understanding the new millennium energy) -- Kryon Book VIII, by Kryon, (Spirit); Lee Carroll. ISBN 978-1-888053-11-1

- ↑ Lewis 1992, pp. 6–7

- ↑ Hanegraaff 1996, pp. 309–10

- ↑ Heindel, Max (1968), New age Vegetarian Cookbook, Rosicrucian Fellowship OCLC 4971259

- ↑ Max, Peter (1971), The Peter Max new age organic vegetarian cookbook, Pyramid Communications OCLC 267219

- ↑ The Global Oneness Commitment. Fast Fasting – New Age Spirituality Dictionary, retrieved 2008-04

- ↑ Heelas 1996, pp. 60–62.

- ↑ Heelas 1996, pp. 62–65.

- ↑ Rupert 1992, pp. 128–129.

- ↑ Rupert 1992, p. 127.

- ↑ Rupert 1992, p. 133.

- ↑ Melton 1992, p. 23; Heelas 1996, p. 86.

- ↑ York 1995, p. 40.

- ↑ David Moore (2002-06-17), Body & Soul, yoga w/o the yoyos, Media Life

- ↑ Rosen, Judith (2002-05-27), Crossing the Boundaries:Regardless of its label, this increasingly mainstream category continues to broaden its subject base, Publishers Weekly, archived from the original on 2008-07-25

- ↑ Cohen, Maurie J. (January 2007), "Consumer credit, household financial management, and sustainable consumption", International Journal of Consumer Studies 31 (1): 57–65, doi:10.1111/j.1470-6431.2005.00485.x

- ↑ Halweil, Brianink; Lisa Mastny, Erik Assadourian, Linda Starke, Worldwatch Institute (2004), State of the World 2004: A Worldwatch Institute Report on Progress Toward a Sustainable Society, W. W. Norton & Company, p. 167, ISBN 978-0-393-32539-3

- ↑ Cortese, Amy (2003-07-20), "Business; They Care About the World (and They Shop, Too)", The New York Times (The New York Times Company), retrieved 2009-02-27

- ↑ Everage, Laura (2002-10-01), "Understanding the LOHAS Lifestyle", The Gourmet Retailer Magazine (The Nielsen Company), retrieved 2009-02-27

- ↑ O'Connor, Ciara, "Becoming whole: an exploration of women's choices in the holistic and New Age movement in Ireland". 220–39 in Olivia Cosgrove et al. (eds), Ireland's new religious movements. Cambridge Scholars, 2011

- ↑ York 1995, p. 42.

- ↑ Heelas 1996, p. 112.

- ↑ Heelas 1996, p. 120.

- ↑ Brown 1992, p. 90.

- ↑ Heelas 1996, p. 121.

- ↑ Heelas 1996, p. 136.

- ↑ Heelas 1996, pp. 137–138.

- ↑ Heelas 1996, p. 142.

- ↑ Heelas 1996, p. 117.

- ↑ Heelas 1996, pp. 118–119.

- ↑ Adams, W.M. (2006). "The Future of Sustainability: Re-thinking Environment and Development in the Twenty-first Century" Report of the IUCN Renowned Thinkers Meeting, 29–31 January 2006, retrieved 2009-02-16

- ↑ Heelas 1996, pp. 74–75.

- ↑ Spring, Joel H. (2004), "Chapter 4: Love the Biosphere: Environmental Ideologies Shaping Global Society", How Educational Ideologies Are Shaping Global Society: Intergovernmental Organizations, NGO's, and the Decline of the Nation-state (illustrated ed.), Mahwah, New Jersey, US: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, p. 119, ISBN 978-0-8058-4915-8, archived from the original on 2010-10-29, retrieved 2009-03-27

- ↑ Satin (1978), p. 199.

- ↑ Lewis 1992, pp. 200–01

- ↑ York 1995, pp. 40–41.

- ↑ York 1995, p. 41.

- ↑ Heelas 1996, pp. 77–78.

- ↑ Lehrer, Paul M.; David H. (FRW) Barlow, Robert L. Woolfolk, Wesley E. Sime (2007), Principles and Practice of Stress Management, Third Edition, New York: Guilford Press, pp. 46–47, ISBN 978-1-59385-000-5

- ↑ 176.0 176.1 Birosik, Patti Jean (1989). The New Age Music Guide. Collier Books. ISBN 978-0-02-041640-1.

- ↑ 177.0 177.1 Werkhoven, Henk N. (1997). The International Guide to New Age Music. Billboard Books / Crown Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-8230-7661-1.

- ↑ Lewis 1992, p. 6; Hanegraaff 1996, p. 3.

- ↑ Lewis & Melton 1992, p. x.

- ↑ Melton 1992, p. 15.

- ↑ Hanegraaff 1996, pp. 4–6.

- ↑ Heelas 1996, p. 5.

- ↑ Melton, J. Gordon (1989), New Age Encyclopaedia, Routledge, ISBN 978-0-8103-7159-0

- ↑ Hanegraaff 1996, pp. 1ff

- ↑ Heelas, Paul (2004), The Spiritual Revolution: Why Religion Is Giving Way to Spirituality (Religion and Spirituality in the Modern World), WileyBlackwell, ISBN 978-1-4051-1959-7

- ↑ 186.0 186.1 Satin, Mark (1978). New Age Politics: Healing Self and Society. Delta Books / Dell Publishing Co. ISBN 978-0-440-55700-5.

- ↑ 187.0 187.1 Roszak, Theodore (1978). Person / Planet: The Creative Disintegration of Industrial Society. Anchor Press / Doubleday. ISBN 978-0-385-00063-5.

- ↑ 188.0 188.1 Ferguson, Marilyn (1980). The Aquarian Conspiracy: Personal and Social Transformation in the 1980s. Jeremy P. Tarcher Inc. ISBN 978-0-87477-191-6.

- ↑ 189.0 189.1 McLaughlin, Corinne; Davidson, Gordon (1994). Spiritual Politics: Changing the World from the Inside Out. Ballantine Books / Random House. ISBN 978-0-345-36983-3.

- ↑ Barkun, Michael (2003). A Culture of Conspiracy: Apocalyptic Visions in Contemporary America. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-23805-3.

- ↑ Hexham 1992, p. 152.

- ↑ Hexham 1992, p. 154.

- ↑ Hexham 1992, p. 156.

- ↑ Stammer, Larry B. (February 8, 2003), "New Age Beliefs Aren't Christian, Vatican Finds", Los Angeles Times (Los Angeles, California, US: Tribune Company), retrieved 2010-10-04

- ↑ 195.0 195.1 Vatican sounds New Age alert, BBC News, 2003-02-04, retrieved 2010-10-27

- ↑ Handbook of vocational psychology by W. Bruce Walsh, Mark Savickas. 2005. p. 358. ISBN 978-0-8058-4517-4.

- ↑ Steinfels, Peter (1990-01-07), "Trying to Reconcile the Ways of the Vatican and the East", New York Times, retrieved 2008-12-05

- ↑ Fitzgerald, Michael L.; Paul Poupard (2003), "Presentations of Holy See's Document on "New Age"", Jesus Christ the Bearer of the Water of Life: a Christian Reflection on the "New Age" (Vatican City: Roman Catholic Church), retrieved 2010-11-06

- ↑ Pike 2004, p. vii.

- ↑ Kelly 1992, p. 136.

- ↑ Hanegraaff 1996, p. 78.

- ↑ 202.0 202.1 202.2 Kelly 1992, p. 138.

- ↑ Kelly 1992, p. 139.

- ↑ Sjöö, Monica (1998).Bristol, England: Green Leaf Bookshop. New Age Channelings - Who Or What Is Being Channeled?, retrieved 2010-06-28

- ↑ Sjöö, Monica. Notes and explanations to accompany Return of the Dark/Light Mother. Originally appeared in From the Flames, Radical Feminism with Spirit, Issue 22 (Winter 1998/99). Sinister Channelings, retrieved 2010-06-28

- ↑ Sjöö, Monica (1999-09-09). Return of the Dark/Light Mother or New Age Armageddon? Towards a Feminist Vision of the Future. Texas: Plain View Press

- ↑ 207.0 207.1 Wilber, Ken (1999), "Introduction to the Third Volume", The Collected Works of Ken Wilber 3, Boston, MA, US: Shambhala Publications, ISBN 978-1-59030-321-4, retrieved 2009-06-12

- ↑ 208.0 208.1 Hanegraaff 1996, p. 250

- ↑ Wouter J. Hanegraaff, New Age Religion and Western Culture, SUNY, 1998, pp.70 ("Ken Wilber [...] defends a transpersonal worldview which qualifies as 'New Age'").

- ↑ Marian de Souza (ed.), International handbook of the religious, moral and spiritual dimensions in education. Dordrecht: Springer 2006, p. 93. ISBN 978-1-4020-4803-6.

- ↑ 211.0 211.1 Yellowtail, Tom, et al; "Resolution of the 5th Annual Meeting of the Traditional Elders Circle" Northern Cheyenne Nation, Two Moons' Camp, Rosebud Creek, Montana; October 5, 1980

- ↑ 212.0 212.1 Working Group on Indigenous Populations, accepted by the UN General Assembly, Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples; UN Headquarters; New York City (13 September 2007).

- ↑ 213.0 213.1 Mesteth, Wilmer, et al (June 10, 1993) "Declaration of War Against Exploiters of Lakota Spirituality." "At the Lakota Summit V, an international gathering of US and Canadian Lakota, Dakota and Nakota Nations, about 500 representatives from 40 different tribes and bands of the Lakota unanimously passed a "Declaration of War Against Exploiters of Lakota Spirituality." The following declaration was unanimously passed."

- ↑ 214.0 214.1 Taliman, Valerie (1993) "Article On The 'Lakota Declaration of War'."

- ↑ 215.0 215.1 Fenelon, James V. (1998), Culturicide, resistance, and survival of the Lakota ("Sioux Nation"), New York: Taylor & Francis, pp. 295–97, ISBN 978-0-8153-3119-3, retrieved 2009-03-16

- ↑ Hobson, G. "The Rise of the White Shaman as a New Version of Cultural Imperialism." in: Hobson, Gary, ed. The Remembered Earth. Albuquerque, NM: Red Earth Press; 1978: 100-108.

- ↑ Aldred, Lisa, "Plastic Shamans and Astroturf Sun Dances: New Age Commercialization of Native American Spirituality" in: The American Indian Quarterly issn.24.3 (2000) pp.329-352. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

- ↑ "White Shamans and Plastic Medicine Men," Terry Macy and Daniel Hart, Native Voices, Indigenous Documentary Film at the University of Washington

- ↑ Churchill, Ward (1992), Fantasies of the Master Race: Literature, Cinema and the Colonization of American Indians, Common Courage Press, p. 304, ISBN 978-0-9628838-7-3

- ↑ 220.0 220.1 220.2 220.3 220.4 220.5 220.6 220.7 220.8 220.9 220.10 220.11 Kyle, Richard G. (Autumn 1995). "The Political Ideas of the New Age Movement". Journal of Church and State, pp. 831–48. Alternate version in Kyle, Richard (1994). The New Age Movement in American Culture. University Press of America, pp. 113–31. ISBN 978-0-7618-0010-1.

- ↑ 221.0 221.1 221.2 221.3 221.4 Cloud, Dana L. (1994). "'Socialism of the Mind': The New Age of Post-Marxism". In Simons, Herbert W.; Billig, Michael, eds. (1994). After Postmodernism: Reconstructing Ideology Critique. SAGE Publications, Chap. 10. ISBN 978-0-8039-8878-1. Alternate version in Cloud, Dana (1997). Control and Consolation in American Life: Rhetoric of Therapy. SAGE Publications, Chap. 6. ISBN 978-0-7619-0506-6.

- ↑ Gottlieb, Annie (1987). Do You Believe in Magic?: Bringing the 60s Back Home. Simon & Schuster, pp. 124–62. ISBN 978-0-671-66050-5.

- ↑ 223.0 223.1 Ray and Anderson (2000), cited above, pp. 188–92. ISBN 978-0-609-60467-0.

- ↑ Capra, Fritjof (1993). "Vorwort". In Satin, Mark (1993). Heile dich selbst und unsere Erde. Arbor Verlag, pp. 1–5. German language publication. ISBN 978-3-924195-01-4.