Nephrotic syndrome

| Nephrotic syndrome | |

|---|---|

_HE.jpg) Histopathological image of diabetic glomerulosclerosis the main cause of nephrotic syndrome in adults. H&E stain. | |

| Classification and external resources | |

| ICD-10 | N04 |

| ICD-9 | 581.9 |

| DiseasesDB | 8905 |

| MedlinePlus | 000490 |

| eMedicine | med/1612 ped/1564 |

| MeSH | D009404 |

Nephrotic syndrome is a nonspecific kidney disorder characterized by a number of signs of disease: proteinuria, hypoalbuminemia and edema.[1] It is characterized by an increase in permeability of the capillary walls of the glomerulus leading to the presence of high levels of protein passing from the blood into the urine (proteinuria at least 3.5 grams per day per 1.73m2 body surface area);[2] ( > 40 mg per square meter body surface area per hour ) low levels of protein in the blood (hypoproteinemia or hypoalbuminemia), ascites and in some cases, edema; high cholesterol (hyperlipidaemia or hyperlipemia) and a predisposition for coagulation.

The cause is damage to the glomeruli, which can be the cause of the syndrome or caused by it, that alters their capacity to filter the substances transported in the blood. The severity of the damage caused to the kidneys can vary and can lead to complications in other organs and systems. However, patients suffering from the syndrome have a good prognosis under suitable treatment.

Kidneys affected by nephrotic syndrome have small pores in the podocytes, large enough to permit proteinuria (and subsequently hypoalbuminemia,<25g/L, because some of the protein albumin has gone from the blood to the urine) but not large enough to allow cells through (hence no haematuria). By contrast, in nephritic syndrome red blood cells pass through the pores, causing haematuria.

Signs and symptoms

It is characterized by proteinuria (>3.5g/day), hypoalbuminemia, hyperlipidaemia, and edema (which is generalized and also known as anasarca or dropsy) that begins in the face. Lipiduria (lipids in urine) can also occur, but is not essential for the diagnosis of nephrotic syndrome. Hyponatremia also occurs with a low fractional sodium excretion.

Hyperlipidaemia is caused by two factors:

- Hypoproteinemia stimulates protein synthesis in the liver, resulting in the overproduction of lipoproteins.

- Lipid catabolism is decreased due to lower levels of lipoprotein lipase, the main enzyme involved in lipoprotein breakdown.[3] Cofactors, such as Apolipoprotein C2 may also be lost by increased filtration of proteins.

A few other characteristics seen in nephrotic syndrome are:

- The most common sign is excess fluid in the body due to the serum hypoalbuminemia. Lower serum oncotic pressure causes fluid to accumulate in the interstitial tissues. Sodium and water retention aggravates the edema. This may take several forms:

- Puffiness around the eyes, characteristically in the morning.

- Pitting edema over the legs.

- Fluid in the pleural cavity causing pleural effusion. More commonly associated with excess fluid is pulmonary edema.

- Fluid in the peritoneal cavity causing ascites.

- Generalized edema throughout the body known as anasarca.

- Most of the patients are normotensive but hypertension (rarely) may also occur.

- Anaemia (iron resistant microcytic hypochromic type) maybe present due to transferrin loss.

- Dyspnea may be present due to pleural effusion or due to diaphragmatic compression with ascites.

- Erythrocyte sedimentation rate is increased due to increased fibrinogen & other plasma contents.

- Some patients may notice foamy or frothy urine, due to a lowering of the surface tension by the severe proteinuria. Actual urinary complaints such as haematuria or oliguria are uncommon, though these are seen commonly in nephritic syndrome.

- May have features of the underlying cause, such as the rash associated with systemic lupus erythematosus, or the neuropathy associated with diabetes.

- Examination should also exclude other causes of gross edema—especially the cardiovascular and hepatic system.

- Muehrcke's nails; white lines (leukonychia) that extend all the way across the nail and lie parallel to the lunula[4]

Clinical symptoms

The main symptoms of nephrotic syndrome are:[6]

- A proteinuria of greater than 3.5 g /24 h /1.73 m² s or 40 mg/h/m2 in children (between 3 and 3.5 g/24 h is considered to be proteinuria in the nephrotic range).[7][8] The ratio between urinary concentrations of albumin and creatinin can be used in the absence of a 24-hour urine test for total protein. This coefficient will be greater than 200–400 mg/mmol in nephrotic syndrome. This pronounced loss of proteins is due to an increase in glomerular permeability that allows proteins to pass into the urine instead of being retained in the blood. Under normal conditions a 24-hour urine sample should not exceed 80 milligrams or 10 milligrams per decilitre.[9]

- A hypoalbuminemia of less than 2.5 g/dL,[7] that exceeds the hepatic clearance level, that is, protein synthesis in the liver is insufficient to increase the low blood protein levels.

- Edema is thought to be caused by two mechanisms. The first being hypoalbuminemia which lowers the oncotic pressure within vessels resulting in hypovolemia and subsequent activation of the Renin-angiotensin system and thus retention of sodium and water. Additionally, it is thought that albumin causes a direct effect on the epithelial sodium channel (ENaC) on the principal cell that leads to the reabsorption of sodium and water. Nephrotic syndrome edema initially appears in parts of the lower body (such as the legs) and in the eyelids. In the advanced stages it also extends to the pleural cavity and peritoneum (ascites) and can even develop into a generalized anasarca. It has been recently seen that intrarenal sodium handling abnormality is related to Atrial Natriuretic Peptide resistance is associated with decreased abundance and altered subcellular localization of dopamine receptor in renal tubules.[10]

- Hyperlipidaemia is caused by an increase in the synthesis of low and very low-density lipoproteins in the liver that are responsible for the transport of cholesterol and triglycerides. There is also an increase in the hepatic synthesis of cholesterol.

- Thrombophilia, or hypercoagulability, is a greater predisposition for the formation of blood clots that is caused by a decrease in the levels of antithrombin III in the blood due to its loss in urine.

- Lipiduria or loss of lipids in the urine is indicative of glomerular pathology due to an increase in the filtration of lipoproteins.[11]

Pathophysiology

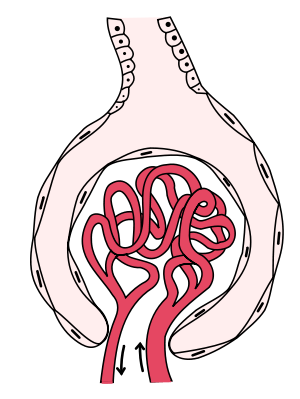

The renal glomerulus filters the blood that arrives at the kidney. It is formed of capillaries with small pores that allow small molecules to pass through that have a molecular weight of less than 40,000 Daltons,[12] but not larger macromolecules such as proteins.

In nephrotic syndrome, the glomeruli are affected by an inflammation or a hyalinization (the formation of a homogenous crystalline material within cells) that allows proteins such as albumin, antithrombin or the immunoglobulins to pass through the cell membrane and appear in urine.[13]

Albumin is the main protein in the blood that is able to maintain an oncotic pressure, which prevents the leakage of fluid into the extracellular medium and the subsequent formation of edemas.

As a response to hypoproteinemia the liver commences a compensatory mechanism involving the synthesis of proteins, such as alpha-2 macroglobulin and lipoproteins.[13] An increase in the latter can cause the hyperlipidemia associated with this syndrome.

Causes and classification

Nephrotic syndrome has many causes and may either be the result of a glomerular disease that can be either limited to the kidney, called primary nephrotic syndrome (primary glomerulonephritis), or a condition that affects the kidney and other parts of the body, called secondary nephrotic syndrome.

Primary glomerulonephritis

Primary causes of nephrotic syndrome are usually described by their histology:[14]

- Minimal change disease (MCD): is the most common cause of nephrotic syndrome in children. It owes its name to the fact that the nephrons appear normal when viewed with an optical microscope as the lesions are only visible using an electron microscope. Another symptom is a pronounced proteinuria.

- Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS): is the most common cause of nephrotic syndrome in adults.[15] It is characterized by the appearance of tissue scarring in the glomeruli. The term focal is used as some of the glomeruli have scars, while others appear intact; the term segmental refers to the fact that only part of the glomerulus suffers the damage.

- Membranous glomerulonephritis (IMN): The inflammation of the glomerular membrane causes increased leaking in the kidney. It is not clear why this condition develops in most people, although an auto-immune mechanism is suspected.[15]

- Mesangial proliferative glomerulonephritis (MPGN): is the inflammation of the glomeruli along with the deposit of antibodies in their membranes, which makes filtration difficult.

- Rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis (RPGN): A patient’s glomeruli are present in a crescent moon shape. It is characterized clinically by a rapid decrease in the glomerular filtration rate (GFR) by at least 50% over a short period, usually from a few days to 3 months.[16]

They are considered to be "diagnoses of exclusion", i.e. they are diagnosed only after secondary causes have been excluded.

Secondary glomerulonephritis

_PAM.jpg)

Secondary causes of nephrotic syndrome have the same histologic patterns as the primary causes, though they may exhibit some difference suggesting a secondary cause, such as inclusion bodies.[17] They are usually described by the underlying cause.

- Diabetic nephropathy: is a complication that occurs in some diabetics. Excess blood sugar accumulates in the kidney causing them to become inflamed and unable to carry out their normal function. This leads to the leakage of proteins into the urine.

- Systemic lupus erythematosus: this autoimmune disease can affect a number of organs, among them the kidney, due to the deposit of immunocomplexes that are typical to this disease. The disease can also cause lupus nephritis.

- Sarcoidosis: This disease does not usually affect the kidney but, on occasions, the accumulation of inflammatory granulomas (collection of immune cells) in the glomeruli can lead to nephrotic syndrome.

- Syphilis: kidney damage can occur during the secondary stage of this disease (between 2 and 8 weeks from onset).

- Hepatitis B: certain antigens present during hepatitis can accumulate in the kidneys and damage them.

- Sjögren's syndrome: this autoimmune disease causes the deposit of immunocomplexes in the glomeruli, causing them to become inflamed, this is the same mechanism as occurs in systemic lupus erythematosus.

- HIV: the virus’ antigens provoke an obstruction in the glomerular capillary’s lumen that alters normal kidney function.

- Amyloidosis: the deposit of amyloid substances (proteins with anomalous structures) in the glomeruli modifying their shape and function.

- Multiple myeloma: the cancerous cells arrive at the kidney causing glomerulonephritis as a complication.

- Vasculitis: inflammation of the blood vessels at a glomerular level impedes the normal blood flow and damages the kidney.

- Cancer: as happens in myeloma, the invasion of the glomeruli by cancerous cells disturbs their normal functioning.

- Genetic disorders: congenital nephrotic syndrome is a rare genetic disorder in which the protein nephrin, a component of the glomerular filtration barrier, is altered.

- Drugs ( e.g. gold salts, penicillin, captopril):[18] gold salts can cause a more or less important loss of proteins in urine as a consequence of metal accumulation. Penicillin is nephrotoxic in patients with kidney failure and captopril can aggravate proteinuria.

Secondary causes by histologic pattern

Membranous nephropathy (MN

- Sjögren's syndrome

- Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE)

- Diabetes mellitus

- Sarcoidosis

- Drugs (such as corticosteroids, gold, intravenous heroin)

- Malignancy (cancer)

- Bacterial infections, e.g. leprosy & syphilis

- Protozoal infections, e.g. malaria

Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS)[19]

Minimal change disease (MCD)[19]

- Drugs, especially NSAIDs in the elderly

- Malignancy, especially Hodgkin's lymphoma

- Allergy

- Bee sting

Membranoproliferative Glomerulonephritis

Diagnosis

Along with obtaining a complete medical history, a series of biochemical tests are required in order to arrive at an accurate diagnosis that verifies the presence of the illness. In addition, imaging of the kidneys (for structure and presence of two kidneys) is sometimes carried out, and/or a biopsy of the kidneys. The first test will be a urinalysis to test for high levels of proteins,[21] as a healthy subject excretes an insignificant amount of protein in their urine. The test will involve a 24-hour bedside urinary total protein estimation. The urine sample is tested for proteinuria (>3.5 g per 1.73 m2 per 24 hours). It is also examined for urinary casts, which are more a feature of active nephritis. Next a blood screen, comprehensive metabolic panel (CMP) will look for hypoalbuminemia: albumin levels of ≤2.5 g/dL (normal=3.5-5 g/dL). Then a Creatinine Clearance CCr test will evaluate renal function particularly the glomerular filtration capacity.[22] Creatinine formation is a result of the breakdown of muscular tissue, it is transported in the blood and eliminated in urine. Measuring the concentration of organic compounds in both liquids evaluates the capacity of the glomeruli to filter blood. Electrolytes and urea levels may also be analysed at the same time as creatinine (EUC test) in order to evaluate renal function. A lipid profile will also be carried out as high levels of cholesterol (hypercholesterolemia), specifically elevated LDL, usually with concomitantly elevated VLDL, is indicative of nephrotic syndrome.

A kidney biopsy may also be used as a more specific and invasive test method. A study of a sample’s anatomical pathology may then allow the identification of the type of glomerulonephritis involved.[21] However, this procedure is usually reserved for adults as the majority of children suffer from minimum change disease that has a remission rate of 95% with corticosteroids.[23] A biopsy is usually only indicated for children that are corticosteroid resistant as the majority suffer from focal and segmental glomeruloesclerosis.[23]

Further investigations are indicated if the cause is not clear including analysis of auto-immune markers (ANA, ASOT, C3, cryoglobulins, serum electrophoresis), or ultrasound of the whole abdomen.

Classification

A broad classification of nephrotic syndrome based on underlying cause:

| Nephrotic syndrome | |||||||||||||||||||

| Primary | Secondary | ||||||||||||||||||

Nephrotic syndrome is often classified histologically:

| Nephrotic syndrome | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| MCD | FSGS | MN | MPGN | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Differential diagnosis

Some symptoms that are present in nephrotic syndrome, such as edema and proteinuria, also appear in other illnesses. Therefore, other pathologies need to be excluded in order to arrive at a definitive diagnosis.[24]

- Edema: in addition to nephrotic syndrome there are two other disorders that often present with edema; these are heart failure and liver failure.[25] Congestive heart failure can cause liquid retention in tissues as a consequence of the decrease in the strength of ventricular contractions. The liquid is initially concentrated in the ankles but it subsequently becomes generalized and is called anasarca.[26] Patients with congestive heart failure also experience an abnormal swelling of the heart cardiomegaly, which aids in making a correct diagnosis. Jugular venous pressure can also be elevated and it might be possible to hear heart murmurs. An echocardiogram is the preferred investigation method for these symptoms. Liver failure caused by cirrhosis, hepatitis and other conditions such as alcoholism, IV drug use or some hereditary diseases can lead to swelling in the lower extremities and the abdominal cavity. Other accompanying symptoms include jaundice, dilated veins over umbilicus (caput medusae), scratch marks (due to widespread itching, known as pruritus), enlarged spleen, spider angiomata, encephalopathy, bruising, nodular liver and anomalies in the liver function tests.[27] Less frequently symptoms associated with the administration of certain pharmaceutical drugs have to be discounted. These drugs promote the retention of liquid in the extremities such as occurs with NSAIs, some antihypertensive drugs, the adrenal corticosteroids and sex hormones.[27]

Acute fluid overload can cause edema in someone with kidney failure. These people are known to have kidney failure, and have either drunk too much or missed their dialysis. In addition, when Metastatic cancer spreads to the lungs or abdomen it causes effusions and fluid accumulation due to obstruction of lymphatic vessels and veins, as well as serous exudation.

- Proteinuria: the loss of proteins from the urine is caused by many pathological agents and infection by these agents has to be ruled out before it can be certain that a patient has nephrotic syndrome. Multiple myeloma can cause a proteinuria that is not accompanied by hypoalbuminemia, which is an important aid in making a differential diagnosis;[28] other potential causes of proteinuria include asthenia, weight loss or bone pain. In diabetes mellitus there is an association between increases in glycated hemoglobin levels and the appearance of proteinuria.[29] Other causes are amyloidosis and certain other allergic and infectious diseases.

Complications

Nephrotic syndrome can be associated with a series of complications that can affect an individual’s health and quality of life:[13]

- Thromboembolic disorders: particularly those caused by a decrease in blood antithrombin III levels due to leakage. Antithrombin III counteracts the action of thrombin. Thrombosis usually occurs in the renal veins although it can also occur in arteries. Treatment is with oral anticoagulants (not heparin as heparin acts via anti-thrombin 3 which is lost in the proteinuria so it will be ineffective.) Hypercoagulopathy due to extravasation of fluid from the blood vessels (edema) is also a risk for venous thrombosis.

- Infections: The increased susceptibility of patients to infections can be a result of the leakage of immunoglobulins from the blood, the loss of proteins in general and the presence of oedematous fluid (which acts as a breeding ground for infections). The most common infection is peritonitis, followed by lung, skin and urinary infections, meningoencephalitis and in the most serious cases septicaemia. The most notable of the causative organisms are Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae.

- Acute kidney failure due to hypovolemia: the loss of vascular fluid into the tissues (edema) produces a decreased blood supply to the kidneys that causes a loss of kidney function. Thus it is a tricky task to get rid of excess fluid in the body while maintaining circulatory euvolemia.

- Pulmonary edema: the loss of proteins from blood plasma and the consequent fall in oncotic pressure causes an abnormal accumulation of liquid in the lungs causing hypoxia and dyspnoea.

- Hypothyroidism: deficiency of the thyroglobulin transport protein thyroxin (a glycoprotein that is rich in iodine and is found in the thyroid gland) due to decreased thyroid binding globulin.

- Hypocalcaemia: lack of 25-hydroxycholecalciferol (the way that vitamin D is stored in the body). As vitamin D regulates the amount of calcium present in the blood a decrease in its concentration will lead to a decrease in blood calcium levels. It may be significant enough to cause tetany. Hypocalcaemia may be relative; calcium levels should be adjusted based on the albumin level and ionized calcium levels should be checked.

- Microcytic hypochromic anaemia: iron deficiency caused by the loss of ferritin (compound used to store iron in the body). It is iron-therapy resistant.

- Protein malnutrition: this occurs when the amount of protein that is lost in the urine is greater than that ingested, this leads to a negative nitrogen balance.[30][31]

- Growth retardation: can occur in cases of relapse or resistance to therapy. Causes of growth retardation are protein deficiency from the loss of protein in urine, anorexia (reduced protein intake), and steroid therapy (catabolism).

- Vitamin D deficiency can occur. Vitamin D binding protein is lost.

- Cushing's Syndrome

Treatment

The treatment of nephrotic syndrome can be symptomatic or can directly address the injuries caused to the kidney.

Symptomatic treatment

The objective of this treatment is to treat the imbalances brought about by the illness:[32] edema, hypoalbuminemia, hyperlipemia, hypercoagulability and infectious complications.

- Edema: a return to an unswollen state is the prime objective of this treatment of nephrotic syndrome. It is carried out through the combination of a number of recommendations:

- Rest: depending on the seriousness of the edema and taking into account the risk of thrombosis caused by prolonged bed rest.[33]

- Medical nutrition therapy: based on a diet with the correct energy intake and balance of proteins that will be used in synthesis processes and not as a source of calories. A total of 35 kcal/kg body weight/day is normally recommended.[34] This diet should also comply with two more requirements: the first is to not consume more than 1 g of protein/kg body weight/ day,[34] as a greater amount could increase the degree of proteinuria and cause a negative nitrogen balance.[31] Patients are usually recommended lean cuts of meat, fish, and poultry. The second guideline requires that the amount of water ingested is not greater than the level of diuresis. In order to facilitate this the consumption of salt must also be controlled, as this contributes to water retention. It is advisable to restrict the ingestion of sodium to 1 or 2 g/day, which means that salt cannot be used in cooking and salty foods should also be avoided.[35] Foods high in sodium include seasoning blends (garlic salt, Adobo, season salt, etc.) canned soups, canned vegetables containing salt, luncheon meats including turkey, ham, bologna, and salami, prepared foods, fast foods, soy sauce, ketchup, and salad dressings. On food labels, compare milligrams of sodium to calories per serving. Sodium should be less than or equal to calories per serving.

- Medication: The pharmacological treatment of edema is based on the prescription of diuretic drugs (especially loop diuretics, such as furosemide). In severe cases of edema (or in cases with physiological repercussions, such as scrotal, preputial or urethral edema) or in patients with one of a number of severe infections (such as sepsis or pleural effusion), the diuretics can be administered intravenously. This occurs where the risk from plasmatic expansion [36] is considered greater than the risk of severe hypovolemia, which can be caused by the strong diuretic action of intravenous treatment. The procedure is the following:

- Analyse haemoglobin and haematocrit levels.

- A solution of 25% albumin is used that is administered for only 4 hours in order to avoid pulmonary edema.

- Haemoglobin and haematocrit levels are analysed again: if the haematocrit value is less than the initial value (a sign of correct expansion) the diuretics are administered for at least 30 minutes. If the haematocrit level is greater than the initial one this is a contraindication for the use of diuretics as they would increase said value.

- It may be necessary to give a patient potassium or require a change in dietary habits if the diuretic drug causes hypokalaemia as a side effect.

- Hypoalbuminemia: is treated using the medical nutrition therapy described as a treatment for edema. It includes a moderate intake of foods rich in animal proteins.[37]

- Hyperlipidaemia: depending of the seriousness of the condition it can be treated with medical nutrition therapy as the only treatment or combined with drug therapy. The ingestion of cholesterol should be less than 300 mg/day,[34] which will require a switch to foods that are low in saturated fats.[38] Avoid saturated fats such as butter, cheese, fried foods, fatty cuts of red meat, egg yolks, and poultry skin. Increase unsaturated fat intake, including olive oil, canola oil, peanut butter, avocadoes, fish and nuts. In cases of severe hyperlipidaemia that are unresponsive to nutrition therapy the use of hypolipidemic drugs, may be necessary (these include statins, fibrates and resinous sequesters of bile acids).[39]

- Thrombophilia: low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) may be appropriate for use as a prophylactic in some circumstances, such as in asymptomatic patients that have no history of suffering from thromboembolism.[40]

[41] When the thrombophilia is such that it leads to the formation of blood clots, heparin is given for at least 5 days along with oral anticoagulants (OAC). During this time and if the prothrombin time is within its therapeutic range (between 2 and 3),[42] it may be possible to suspend the LMWH while maintaining the OACs for at least 6 months.[43]

- Infectious complications: an appropriate course of antibacterial drugs can be taken according to the infectious agent.

In addition to these key imbalances, vitamin D and calcium are also taken orally in case the alteration of vitamin D causes a severe hypocalcaemia, this treatment has the goal of restoring physiological levels of calcium in the patient.[44]

- Achieving better blood glucose level control if the patient is diabetic.

- Blood pressure control. ACE inhibitors are the drug of choice. Independent of their blood pressure lowering effect, they have been shown to decrease protein loss.

Treatment of kidney damage

The treatment of kidney damage may reverse or delay the progression of the disease.[32] Kidney damage is treated by prescribing drugs:

- Corticosteroids: the result is a decrease in the proteinuria and the risk of infection as well as a resolution of the edema.[45] Prednisone is usually prescribed at a dose of 60 mg/m² of body surface area/day in a first treatment for 4–8 weeks. After this period the dose is reduced to 40 mg/m² for a further 4 weeks. Patients suffering a relapse or children are treated with prednisolone 2 mg/kg/day till urine becomes negative for protein. Then, 1.5 mg/kg/day for 4 weeks. Frequent relapses treated by: cyclophosphamide or nitrogen mustard or cyclosporin or levamisole. Patients can respond to prednisone in a number of different ways:

- Corticosteroid sensitive patient or early steroid-responder: the subject responds to the corticosteroids in the first 8 weeks of treatment. This is demonstrated by a strong diuresis and the disappearance of edemas, and also by a negative test for proteinuria in three urine samples taken during the night.

- Corticosteroid resistant patient or late steroid-responder: the proteinuria persists after the 8-week treatment. The lack of response is indicative of the seriousness of the glomerular damage, which could develop into chronic kidney failure.

- Corticosteroid tolerant patient: complications such as hypertension appear, patients gain a lot of weight and can develop aseptic or avascular necrosis of the hip or knee,[46] cataracts and thrombotic phenomena and/or embolisms.

- Corticosteroid dependent patient: proteinuria appears when the dose of corticosteroid is decreased or there is a relapse in the first two weeks after treatment is completed.

- Immunosupressors (cyclophosphamide): only indicated in recurring nephrotic syndrome in corticosteroid dependent or intolerant patients. In the first two cases the proteinuria has to be negated before treatment with the immunosuppressor can begin, which involves a prolonged treatment with prednisone. The negation of the proteinuria indicates the exact moment when treatment with cyclophosphamide can begin. The treatment is continued for 8 weeks at a dose of 3 mg/kg/day, the immunosuppression is halted after this period. In order to be able to start this treatment the patient should not be suffering from neutropenia nor anaemia, which would cause further complications. A possible side effect of the cyclophosphamide is alopecia. Complete blood count tests are carried out during the treatment in order to give advance warning of a possible infection.

Epidemiology

Nephrotic syndrome can affect any age, although it is mainly found in adults with a ratio of adults to children of 26 to 1.[47]

The syndrome presents in different ways in the two groups: the most frequent glomerulopathy in children is minimal change disease (66% of cases), followed by focal and segmental glomeruloesclerosis (8%) and mesangiocapillary glomerulonephritis (6%).[17] In adults the most common disease is mesangiocapillary glomerulonephritis (30-40%), followed by focal and segmental glomeruloesclerosis (15-25%) and minimal change disease (20%). The latter usually presents as secondary and not primary as occurs in children. Its main cause is diabetic nephropathy.[17] It usually presents in a patient’s 40s or 50s. Of the glomerulonephritis cases approximately 60% to 80% are primary, while the remainder are secondary.[47]

There are also differences in epidemiology between the sexes, the disease is more common in men than in women by a ratio of 2 to 1.[47]

The epidemiological data also reveals information regarding the most common way that symptoms develop in patients with nephrotic syndrome:[47] spontaneous remission occurs in up to 20% or 30% of cases during the first year of the illness. However, this improvement is not definitive as some 50% to 60% of patients die and / or develop chronic renal failure 6 to 14 years after this remission. On the other hand, between 10% and 20% of patients have continuous episodes of remissions and relapses without dying or jeopardizing their kidney. The main causes of death are cardiovascular, as a result of the chronicity of the syndrome, and thromboembolic accidents.

Prognosis

The prognosis for nephrotic syndrome under treatment is generally good although this depends on the underlying cause, the age of the patient and their response to treatment. It is usually good in children, because minimal change disease responds very well to steroids and does not cause chronic renal failure. Any relapses that occur become less frequent over time;[48] the opposite occurs with mesangiocapillary glomerulonephritis, in which the kidney fails within three years of the disease developing, making dialysis necessary and subsequent kidney transplant.[48] In addition children under the age of 5 generally have a poorer prognosis than prepubescents, as do adults older than 30 years of age as they have a greater risk of kidney failure.[49]

Other causes such as focal segmental glomerulosclerosis frequently lead to end stage renal disease. Factors associated with a poorer prognosis in these cases include level of proteinuria, blood pressure control and kidney function (GFR).

Without treatment nephrotic syndrome has a very bad prognosis especially rapidly progressing glomerulonephritis, which leads to acute kidney failure after a few months.

See also

References

- ↑ http://wordnetweb.princeton.edu/perl/webwn?s=nephrotic%20syndrome

- ↑ "ELECTRONIC LEARNING MODULE for KIDNEY and URINARY TRACT DISEASES". Retrieved 2008-11-26.

- ↑ http://www.hawaii.edu/medicine/pediatrics/pedtext/s13c02.html

- ↑ Freedberg, Irwin M. et.al, ed. (2003). Fitzpatrick's dermatology in general medicine. (6th ed.). New York, NY [u.a.]: McGraw-Hill. p. 659. ISBN 0-07-138076-0.

- ↑ Behrman, Richard E.; Robert M Kliegman; Hal B. Jenson (2008). Nelson Tratado de Pediatria (in Spanish). Elsevier, España. p. 1755. ISBN 8481747475.

- ↑ "Manifestaciones clínicas del síndrome nefrótico" (PDF). See table 4.2. Retrieved 12-09-2008. Check date values in:

|accessdate=(help) - ↑ 7.0 7.1 García - Conde, J.; Merino Sánchez, J.; González Macías, J. (1995). "Fisiopatología glomerular". Patología General. Semiología Clínica y Fisiopatología. McGraw - Hill Interamericana. ISBN 8448600932.

- ↑ Parra Herrán, Carlos Eduardo; Castillo Londoño, Juan Sebastián; López Panqueva, Rocío del Pilar; Andrade Pérez, Rafael Enrique. "Síndrome nefrótico y proteinuria en rango no nefrótico". Retrieved 2008-09-14.

- ↑ "Valores normales de proteína en orina de 24 horas". Retrieved 24 August 2012.

- ↑ Cátia Fernandes-Cerqueira, Benedita Sampaio-Maia, Janete Quelhas-Santos, Mónica Moreira-Rodrigues, Liliana Simões-Silva, Ana M. Blazquez-Medela, C. Martinez-Salgado, Jose M. Lopez-Novoa, and Manuel Pestana (2013). "Concerted Action of ANP and Dopamine D1-Receptor to Regulate Sodium Homeostasis in Nephrotic Syndrome". BioMed Research International 2013 (397391). doi:10.1155/2013/397391. PMC 3727124. PMID 23956981.

- ↑ "La pérdida de lipoproteínas en la orina". Retrieved 2008-11-21.

- ↑ "Apuntes de fisiopatología de sistemas". Retrieved 08-09-2008. Check date values in:

|accessdate=(help) - ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Durán Álvarez, Sandalio. "Complicaciones agudas del síndrome nefrótico". Retrieved 11-09-2008. Check date values in:

|accessdate=(help) - ↑ "Descripción histológica de las glomerulonefritis ideopáticas". Retrieved 08-09-2008. Check date values in:

|accessdate=(help) - ↑ 15.0 15.1 "Patient information: The nephrotic syndrome (Beyond the Basics)". Retrieved 2013-06-28.

- ↑ James W Lohr, MD. "Rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis". Retrieved 2013-06-28.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 "Frecuencia de las glomerulonefritis y causas de las glomerulonefritis secundarias". Retrieved 08-09-2008. Check date values in:

|accessdate=(help) - ↑ "Fármacos que pueden producir síndrome nefrótico". Retrieved 08-09-2008. Check date values in:

|accessdate=(help) - ↑ 19.0 19.1 Fogo AB, Bruijn JA. Cohen AH, Colvin RB, Jennette JC. Fundamentals of Renal Pathology. Springer. ISBN 978-0-387-31126-5.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 "Nephrotic syndrome". Retrieved 08-06-2013. Check date values in:

|accessdate=(help) - ↑ 21.0 21.1 "Nefrología y urología". Retrieved 12-09-2008. Check date values in:

|accessdate=(help) - ↑ "El diagnóstico del síndrome nefrótico". Retrieved 12-09-2008. Check date values in:

|accessdate=(help) - ↑ 23.0 23.1 Voguel S, Andrea; Azócar P, Marta; Nazal Ch, Vilma; Salas del C, Paulina. "Indicaciones de la biospsia renal en niños". Retrieved 2008-09-14.

- ↑ "Diagnóstico diferencial en el síndrome nefrótico". Retrieved 2008-09-14.

- ↑ Harold Friedman, H (2001). "General problems". Problem-oriented Medical Diagnosis (Seventh ed.). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 3 and 4. ISBN 0-7817-2909-2.

- ↑ "El edema en la insuficiencia cardíaca". Retrieved 2008-09-14.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Goldman, Lee; Braunwald, Eugene (2000). "Edemas". Cardiología en atención primaria. Harcourt. pp. 114–117. ISBN 8481744328.

- ↑ Rivera, F; Egea, J.J; Jiménez del Cerro, L.A; Olivares,J. "La proteinuria en el mieloma múltiple". Retrieved 2008-09-14.

- ↑ Bustillo Solano, Emilio. "Relación de la proteinuria con el nivel de hemoglobina glicosilada en los diabéticos". Retrieved 2008-09-14.

- ↑ Zollo, Anthony J (2005). "Nefrología". Medicina interna. Secretos (Cuarta ed.). Elsevier España. p. 283. ISBN 8481748862.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 "Balance de nitrógeno y equilibrio nitrogenado". Retrieved 08-09-2008.

It occurs during renal pathologies, during fasting, in eating disorders or during heavy physical exercise.

Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ↑ 32.0 32.1 Curtis, Michael J.; Page, Clive P.; Walker, Michael J.A; Hoffman, Brian B. (1998). "Fisiopatología y enfermedades renales". Farmacología integrada. Harcourt. ISBN 8481743402.

- ↑ Saz Peiro, Pablo. "El reposo prolongado" (PDF). Retrieved 08-09-2008. Check date values in:

|accessdate=(help) - ↑ 34.0 34.1 34.2 "Dietoterapia del síndrome nefrótico". Retrieved 08-09-2008. Check date values in:

|accessdate=(help) - ↑ "Lista de alimentos ricos en sodio". Retrieved 08-09-2008. Check date values in:

|accessdate=(help) - ↑ "Fluidoterapia: tipos de expansores" (PDF). Retrieved 08-09-2008.

Plasma expanders are natural or synthetic substances (dextran, albumin...), that are able to retain liquid in the vascular space.

Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ↑ "Lista de alimentos ricos en proteínas". Retrieved 08-09-2008.

Expressed as grams per 100 g of food.

Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ↑ "Sustitución de los alimentos ricos en grasas de la dieta". Retrieved 08-09-2008.

Organizations in the US recommend that no more than 30% of total daily calorie intake is from fats.

Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ↑ Martín Zurro, Armando (2005). "Hipolipemiante, diuréticos, estatina.". Compendio de atención primaria: Conceptos, organización y práctica clínica (Segunda ed.). Elsevier España. p. 794. ISBN 8481748161.

- ↑ Jiménez Alonso, Juan. "Profilaxis de los fenómenos tromboembólicos" (PDF). Retrieved 2008-09-14.

- ↑ Glassock RJ (August 2007). "Prophylactic anticoagulation in nephrotic syndrome: a clinical conundrum". J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 18 (8): 2221–5. doi:10.1681/ASN.2006111300. PMID 17599972.

- ↑ "Rango Internacional Normalizado (INR)". Retrieved 2008-09-14.

- ↑ "Tratamiento de la hipercoagulabilidad". Retrieved 2008-09-14.

- ↑ "Tratamiento de la hipocalcemia". Retrieved 2008-09-14.

- ↑ Hodson E, Willis N, Craig J (2007). Hodson, Elisabeth M, ed. "Corticosteroid therapy for nephrotic syndrome in children". Cochrane database of systematic reviews (Online) (4): CD001533. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001533.pub4. PMID 17943754.

- ↑ According to MedlinePlus, avascular necrosis is the death of the bone caused by insufficient blood supply to the bone.

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 47.2 47.3 Borrego R., Jaime; Montero C.,, Orlando (2003). Nefrología: Fundamentos de medicina (Cuarta ed.). Corporación para investigaciones biológicas. p. 340. ISBN 9589400639.

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 Guerrero Fernández, J. "Pronóstico de la enfermedad". Retrieved 12-09-2008. Check date values in:

|accessdate=(help) - ↑ "Síndrome nefrótico idiopático: diagnóstico histológico por biopsia renal percutanea". Retrieved 12-09-2008. Check date values in:

|accessdate=(help)

External links

- Nephrotic Syndrome Research A team of kidney doctors and scientists from Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center / Harvard Medical School working to learn more about the cause of Nephrotic Syndrome in children and adults, with an emphasis on the genetic basis of this disease.

- Childhood Nephrotic Syndrome - National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK), NIH

- Adult Nephrotic Syndrome - National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK), NIH

- Kidcomm.org A resource for parents of children with nephrotic syndrome since 2007

- Clardy, Chris (May 2000) "Nephrotic Syndrome in Children" Pediatric Nephrology Handout

- Goldstein, Adam; Trachtman, Howard "Pediatric Nephrotic Syndrome"

- Nephrotic syndrome - Medline Plus

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||