Neonatal meningitis

Neonatal meningitis is a serious medical condition in infants. Meningitis is an inflammation of the meninges (the protective membranes of the central nervous system (CNS)) and is more common in the neonatal period (infants less than 44 days old) than any other time in life and is an important cause of morbidity and mortality globally.[1][2] Mortality is roughly half in developing countries and ranges from 8%-12.5% in developed countries.[2][3]

Symptoms seen with neonatal meningitis are often unspecific that may point to several conditions, such as sepsis (whole body inflammation). These can include fever, irritability, and dyspnea. The only method to determine if meningitis is the cause of these symptoms is lumbar puncture (LP; an examination of the cerebrospinal fluid).[1][4]

The most common causes of neonatal meningitis is bacterial infection of the blood, known as bacteremia (specifically Group B Streptococci (GBS; Streptococcus agalactiae), Escherichia coli, and Listeria monocytogenes).[1] Although there is a low mortality rate in developed countries, there is a 50% prevalence rate of neurodevelopmental disabilities in E. coli and GBS meningitis, while having a 79% prevalence for non-E. coli Gram-negative caused meningitis.[1] Delayed treatment of neonatal meningitis may cause include cerebral palsy, blindness, deafness, and learning deficiencies.[5]

Signs and Symptoms

The following is a list of common signs and symptoms found with neonatal meningitis.

- Fever

- poor appetite

- anterior fontanelle bulging

- seizure

- jitteriness

- dyspnea

- irritability

- anorexia

- vomiting

- diarrhea

- abdominal distention (increase in abdominal size)

- neck rigidity

- cyanosis

- jaundice

- and sunset eyes (downward gaze of the eyes)

- abnormal body temperature (hypo-or hyperthermia)

- change of activity (lethargy or irritability)

Unfortunately these symptoms are unspecific and may point to many different conditions.[4]

Laboratory features

Laboratory features that are characteristic of neonatal bacterial meningitis include:[6]

- Isolation of a bacterial pathogen from the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) by culture and/or visualization by Gram stain

- Increased CSF white blood cell (WBC) count (typically >1000 WBC/mL, but may be lower, especially with gram-positive organisms) with a predominance of neutrophils

- Elevated CSF protein concentration (>150 mg/dL in preterm (premature birth) and >100 mg/dL in term (on time) infants)

- Decreased CSF glucose concentration (<20 mg/dL [1.1 mmol/L] in preterm (premature birth) and <30 mg/dL [1.7 mmol/L] in term (on time) infants)

Causes

Neonatal meningitis is mostly caused by Group B Streptococci (GBS; Streptococcus agalactiae 39%-48% of cases), Escherichia coli (30%-35%), Other Gram-negative rods (8%-12%), Streptococcus pneumoniae (~6%), and Listeria monocytogenes (5%-7%).[1] Most neonatal meningitis results from bacteremia (bacterial infection of the blood)[4][5]

Early-onset

In early-onset neonatal meningitis, acquisition of the bacteria is from the mother before the baby is born or during birth. The most common bacteria found in early-onset are group B Streptococcus (GBS), Esherichia coli, and Listeria monocytogenes. In developing countries, Gram-negative enteric (gut) bacteria are responsible for the majority of early onset meningitis.[1]

Late-onset

Late-onset meningitis is most likely infection from the community. Late onset meningitis may be caused by other Gram-negative bacteria and staphylococcal species. In developing countries Streptococcus pneumoniae accounts for most cases of late onset.[1]

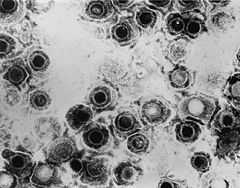

Herpes Simplex Virus

Herpes simplex virus (HSV) is a rare cause of meningitis, occurring only 0.165 in 10,000 live births in the UK and 0.2-5 in 10,000 live births in the US[2][4][7] Both HSV-1 and HSV-2 can cause neonatal meningitis, however, HSV-2 accounts for 70% of the cases.

HSV is transmitted to the neonate mainly during delivery (when infected maternal secretions come into contact with the baby and accounting for 85% of cases), but also occur in utero (while the fetus is still in the womb, 5% of cases) or even post-delivery, receiving the infection from the community (10% of cases).[7] The most important factors impacting the transmission of the virus is the stage of the mother's infection (symptomatic or non-symptomatic) and the damage of any maternal membranes during birth (the longer the tissue is damaged, the higher the chance of neonatal infection).[7]

Pathogenesis

Generally, the progression of neonatal meningitis starts with bacteria colonizing the gastrointestinal tract. The bacteria then invades through the intestinal mucosa layer into the blood, causing bacteremia followed by invasion of the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). The neonate’s less efficient immune system (especially the alternative complement system) lessens their defense against invading bacteria . Colonization of the mother plays an important role in transmission to the neonate, causing early-onset meningitis.[5]

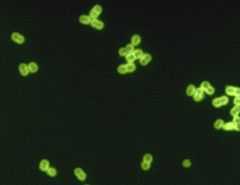

Group B Streptococcus

Neonatal GBS infection is acquired in utero (while the baby is still in the womb) or during passage through the vagina. Evidence suggests that vaginal colonization GBS during pregnancy increases the risk of vertical transmission and early-onset disease in neonates.[8]

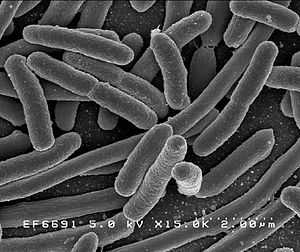

Neonatal meningitis-causing E. coli (NMEC)

NMEC have a capsule (called K1) which protects the bacteria from the innate immune system and allows it to penetrate the CSF. The capsule contains sialic acid, which is found widely in humans and so does not set off the defenses of the body. Sialic acid also plays a role in the bacteria’s ability to invade through the blood-brain barrier. The capsule can be variably O acetylated.[5]

Diagnosis

Bacterial Infection

A lumbar puncture (LP) is necessary to diagnose meningitis. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) culture is the most important study for the diagnosis of neonatal bacterial meningitis because clinical signs are non-specific and unreliable. Blood cultures may be negative in 15-55% of cases, deeming it unreliable as well.[1] However, a CSF/blood glucose ratio below two-thirds has a strong relationship to bacterial meningitis.[9] A LP should be done in all neonates with suspected meningitis, with suspected or proven sepsis (whole body inflammation) and should be considered in all neonates in whom sepsis is a possibility. The role of the LP in neonates who are healthy appearing but have maternal risk factors for sepsis is more controversial; the yield of the LP in these patients may be low.[1][9] Early-onset is deemed when infection is within one week of birth. Late-onset is deemed after the first week.[3]

Viral Infection

Babies born from mothers with symptoms of Herpes Simplex Virus (HSV) should be tested for viral infection. Liver tests, complete blood count (CBC), cerebrospinal fluid analyses, and chest X-ray should all be completed to diagnose meningitis.[7] Samples should be taken from skin, conjunctiva (eye), mouth and throat, rectum, urine, and the CSF for viral culture and PCR analysis with respect to the sample from CSF.

Prevention

Bacterial

Prevention of neonatal meningitis is primarily intrapartum (during labor) antibiotic prophylaxis (prevention) of pregnant mothers to decrease chance of early-onset meningitis by GBS. For late-onset meningitis, prevention is passed onto the caretakers to stop the spread of infectious microorganisms. Proper hygiene habits are first and foremost, while stopping improper antibiotic use; such as over-prescriptions, use of broad spectrum antibiotics, and extended dosing times will aid prevention of late-onset neonatal meningitis. A possible prevention may be vaccination of mothers against GBS and E. coli, however, this is still under development.[1][9]

Viral

the only form of prevention from viral infection of the neonate is a caesarean section form of delivery if the mother is showing symptoms of infection.[7]

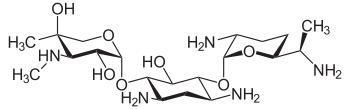

Treatment and Management

Treatment for meningitis is antibiotics. The particular drugs used are based off the infecting bacteria, but a mix of ampicillin, gentamicin, and cefotaxime is used for early-onset meningitis before identification of infection. A regimen of antistaphylococcal antibiotic, such as nafcillin or vancomycin, plus cefotaxime or ceftazidime with or without an aminoglycoside is recommended for late-onset neonatal meningitis. The aim for these treatments is to sterilize the CSF of any meningitis-causing pathogens. A repeated LP 24–48 hours after initial treatment should be used to declare sterilization.[1][9]

Group B Streptococci

For suspected GBS meningitis, the following treatment is recommended by the American Academy of Pediatrics: doses of penicillin up to 450 000 U/kg daily (270 mg/kg/day) divided 8 hourly if <7 days of age and divided 6 hourly if >7 days of age. For penicillin [the recommended dose is up to 300 mg/kg/daily divided 8 hourly if <7 days of age or 4–6 hourly if >7 days of age. After confirmation of GBS, penicillin alone should be used for the rest of the treatment, including the 14 day post-sterilization therapy.[1][9]

Gram-negative Enteric

For suspected Gram-negative enteric(including E. coli) meningitis a combination of cefotaxime and aminoglycoside, usually gentamicin, is recommended. This treatment should last for 14 days after sterilization and then only cefotaxime for another 7 days creating a minimum of 21 days of therapy post-sterilization.[1][9]

Listeria monocytogenes

L. meningitis should be treated with a combination of ampicillin and gentamicin because it is synergistic in vitro and provides more rapid bacterial clearance in animal models of infection. After sterilization of CSF, ampicillin should be stopped and gentamicin continued for another 14 days.[1][9]

Streptococcus pneumoniae

S. pneumonia can be treated with a combination of penicillin and ampicillin.[1][9]

Herpes Simplex Virus

In cases of herpes simplex virus-derived meningitis, antiviral therapy (acyclovir or vidarabine) must be started immediately for a favorable outcome.[1][9] Acyclovir is a better antiviral because it shows a similar effect on the infection as vidarabine and is safer to use in the neonate. The recommended dosage is 20 mg/kg every six hours for 21 days.[7]

Complications

Neuroimaging (X-ray imaging of the brain) is recommended to detect the complications of meningitis. Complications should be suspected when the clinical course is characterized by shock, respiratory failure, focal neurological deficits, a positive CSF culture after 48–72 hours of appropriate antibiotic therapy, or infection with certain organisms, such as Citrobacter koseri and Cronobacter sakazakii for example. Ultrasounds are useful for early imaging to determine ventricular size and hemorrhaging. CT scans later in the therapy should be used to dictate prolonged treatment.[1][9] If intracranial abscesses (collection of pus in the brain) are found, treatment consisting of a combination of surgical drainage of the abscess and antimicrobial therapy for 4–6 weeks is recommended. More imaging should be completed after the end of antibiotic treatment because abscesses have been found after weeks from start of treatment.[9] Relapses have also occurred after appropriate treatment when infected by Gram-negative enteric bacilli, so follow ups are needed in cases of Gram-negative derived meningitis.[9]

Epidemiology

In industrialized countries, the incidence of bacterial meningitis is approximately 3 in 10,000 live births.The incidence of HSV meningitis is estimated to be 0.2-5.0 cases per 10,000 live births. Neonatal meningitis is much more common in developing countries. Neonatal meningitis ranges from 4.8 per 10,000 live births in Hong Kong to 24 per 10,000 live births in Kuwait. In Africa and South Asia, figures ranging from 8.0 to 61 per 10,000 live births are found. It is expected that these numbers are lower than reality due to the difficulty of diagnosing and the healthcare available to underdeveloped countries in Asia and Africa.[2][3]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 1.8 1.9 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 1.16 Heath, P. T., Yusoff, N. N., & Baker, C. J. (2003). Neonatal meningitis.Archives of Disease in Childhood-Fetal and Neonatal Edition, 88(3), F173-F178.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Dredge, D. C., & Krishnamoorthy, K. S. (2012, Sept 05).Neonatal meningitis. Retrieved from http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1176960-overview

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Furyk, J. S., Swann, O., & Molyneux, E. (2011). Systematic review: neonatal meningitis in the developing world. Tropical Medicine & International Health,16(6), 672-679.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Lin, M. C., Chi, H., Chiu, N. C., Huang, F. Y., & Ho, C. S. (2012). Factors for poor prognosis of neonatal bacterial meningitis in a medical center in Northern Taiwan. Journal of Microbiology, Immunology and Infection.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Wilson, B. A., Salyers, A. A., Whitt, D. D., & Winkler, M. E. (2011). Bacterial pathogenesis. (3rd ed., pp. 212-213, 441). Washington D.C.: American Society for Microbiology.

- ↑ Edwards, M. S., & Baker, C. J. (2012, Oct). Clinical features and diagnosis of bacterial meningitis in the neonate. Retrieved from http://www.uptodate.com/contents/clinical-features-and-diagnosis-of-bacterial-meningitis-in-the-neonate?source=search_result&search=neonatal meningitis&selectedTitle=1~7

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 Kimberlin, D. (2004). Herpes simplex virus, meningitis and encephalitis in neonates. breast, 20, 22.

- ↑ Puopolo, K. M., & Baker, C. J. (2012, Oct). Group b streptococcal infection in neonates and young infants. Retrieved from http://www.uptodate.com/contents/group-b-streptococcal-infection-in-neonates-and-young-infants?source=see_link

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 9.6 9.7 9.8 9.9 9.10 9.11 Sivanandan, S., Soraisham, A. S., & Swarnam, K. (2011). Choice and duration of antimicrobial therapy for neonatal sepsis and meningitis. International Journal of Pediatrics, 2011