Neisseria

| Neisseria | |

|---|---|

| |

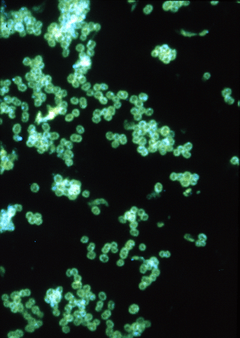

| Fluorescent antibody stain of Neisseria gonorrhoeae. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Bacteria |

| Phylum: | Proteobacteria |

| Class: | Betaproteobacteria |

| Order: | Neisseriales |

| Family: | Neisseriaceae |

| Genus: | Neisseria Trevisan, 1885 |

| Species | |

|

N. bacilliformis | |

Neisseria is a large genus of bacteria that colonize the mucosal surfaces of many animals. Of the 11 species that colonize humans, only two are pathogens, N. meningitidis and N. gonorrhoeae. Most gonoccocal infections are asymptomatic and self-resolving, and epidemic strains of the meningococcus may be carried in >95% of a population where systemic disease occurs at <1% prevalence.

Neisseria species are Gram-negative bacteria included among the proteobacteria, a large group of Gram-negative forms. Neisseria diplococci resemble coffee beans when viewed microscopically.[1]

Species

Pathogens

This genus (family Neisseriaceae) of parasitic bacteria grow in pairs and occasionally tetrads, and thrive best at 98.6°F (37°C) in the animal body or serum media.

The genus includes:

- N. gonorrhoeae (also called the gonococcus), which causes gonorrhea.

- N. meningitidis (also called the meningococcus), one of the most common causes of bacterial meningitis and the causative agent of meningococcal septicaemia.

These two species have the ability of 'breaching' the barrier. Local cytokines of the area become secreted in order to initiate an immune response. However, neutrophils are not able to do their job due to the ability of "Neisseria" to invade and replicate within neutrophils as well avoiding phagocytosis and being killed by complement by resisting opsonization by antibodies, which target the pathogen for destruction. "Neisseria" are also able to alter its antigens to avoid being engulfed by a process called antigenic variation, which is observed primarily in surface-located molecules. The pathogenic species along with some commensal species, have a Type IV pili which serves multiple functions for this organism. Some functions of the type IV pili include: mediating attachment to various cells and tissues, twitching motility, natural competence, microcolony formation, extensive intrastrain phase and antigenic variation.

Complement Inhibition

Fa(fHbp) that is exhibited in N. meningitis and some commensal species, is the main inhibitor of the alternative complement pathway. fHbp protects meningococci from complement-mediated death in human serum experiments, but has also been shown to protect meningococci from anti-microbial peptides in vitro. Factor H binding protein is key to the pathogenesis of Neisseria meningitis, and is therefore important as a potential vaccine candidate.[2] Porins are also an important factor for complement inhibition for both pathogenic and commensal species. Porins are important for nutrient acquisition. Porins are also recognized by TLR2, they bind complement factors (C3b, C4b, factor H, and C4bp (complement factor 4b-binding protein)). Cooperation with pili for CR3-mediated internalization is another function of porins. Ability to translocate into host cells and modulate ROS production and apoptosis is made possible by porins as well. Strains of the same species can express different porins.

Nonpathogens

This genus also contains several, believed to be commensal, or nonpathogenic, species, like:

- Neisseria bacilliformis

- Neisseria cinerea

- Neisseria elongata

- Neisseria flavescens

- Neisseria lactamica

- Neisseria macacae

- Neisseria mucosa

- Neisseria polysaccharea

- Neisseria sicca

- Neisseria subflava

- Neisseria flava

However, some of these can be associated with disease.[3]

History

The genus Neisseria is named after the German bacteriologist Albert Neisser, who in 1879 discovered its first example, Neisseria gonorrheae, the pathogen which causes the human disease gonorrhea. Neisser also co-discovered the pathogen that causes leprosy, Mycobacterium leprae. These discoveries were made possible by the development of new staining techniques which he helped to develop.

Biochemical identification

All the medically significant species of Neisseria are positive for both catalase and oxidase. Different Neisseria species can be identified by the sets of sugars from which they will produce acid. For example, N. gonorrheae makes acid from only glucose, but N. meningitidis produces acid from both glucose and maltose.

Polysaccharide capsule N. meningitidis has a polysaccharide capsule that surrounds the outer membrane of the bacterium and protects against soluble immune effector mechanisms within the serum. It is considered to be an essential virulence factor for the bacteria.[4] N. gonorrhea possesses no such capsule. Instead of having the usual lipopolysaccharide or LPS, this bacteria, whether a pathogenic or commensal species, have what is called a LOS or Lipooligosaccharide which consists of a core polysaccharide and lipid A. It functions as an endotoxin, protects against antimicrobial peptides, and adheres to the Asialoglycoprotein receptor on urethral cells. LOS is highly stimulatory to the human immune system. LOS sialylation (by the enzymes Lst) prevents complement deposition and phagocytosis by neutrophils. LOS modification by phosphoethanolamine (by the enzyme LptA) provides resistance to antimicrobial peptides and complement. Strains of the same species have the ability to produce different LOS glycoforms.

Iron Acquisition

Iron is absolutely required by all life forms, playing a critical role in a number of essential processes. Free iron, at least what would be readily available to a microbial pathogen, practically doesn’t exist in animals. In vertebrates the majority of iron is stored inside cells in complex with either ferritin or hemoglobin. Extracellular iron is found in body fluids complexed to either transferrin or lactoferrin.

Pathogens Acquire Iron by two different strategies:

- ‘Siderophore’-mediated iron uptake, which involves out-competing transferrin and/or lactoferrin for iron binding. Iron-bound siderophores are then taken into the bacterium via specific receptors

- Direct uptake of iron-bound host proteins, that involves the bacteria possessing a high-affinity for transferrin, lactoferrin, and hemoglobin (the approach utilized by the pathogenic "neiserria spp.").

Receptors: HmbRm, HpuA and HpuB are receptors for haptoglobin-haemoglobin. LbpAB is a receptor for human lactoferrin. TbpAB (Tbp1-Tbp2) is a receptor for human transferrin. All of these receptors are utilized for iron acquisition for both pathogenic and commensal species.

Vaccine

Diseases caused by N. meningitidis and N. gonorrhoeae are significant health problems worldwide, the control of which are largely dependent on the availability and widespread use of comprehensive meningococcal and gonococcal vaccines. Development of neisserial vaccines has been challenging due to the nature of these organisms, in particular the heterogeneity, variability and/or poor immunogenicity of their outer surface components. As strictly human pathogens, they are highly adapted to the host environment, but have evolved several mechanisms to remain adaptable to changing microenvironments and avoid elimination by the host immune system. Currently, serogroup A, C, Y and W-135 meningococcal infections can be prevented by vaccines. However, no comprehensive serogroup B vaccine is available, and the prospect of developing a gonococcal vaccine is remote.[5]

Antibiotic resistance

Diseases caused by the pathogenic Neisseria (N. gonorrhoeae and N. meningitidis) have been successfully treated with antibiotics for the past 70 years. However, the prevalence of strains with resistance to antibiotics is increasing. Given the global nature of gonococcal and meningococcal diseases, the worldwide distribution of antibiotics, differing social practices in controlling and monitoring antibiotic availability, and geographical differences in treatment regimens, the global problem of antibiotic resistance likely will continue in the future. By understanding the mechanisms of antibiotic resistance in gonococci and meningococci, resistance to antibiotics currently in clinical practice can be anticipated and the design of novel antimicrobials to circumvent this problem can be undertaken more rationally.[6] The acquisition of cephalosporin resistance in N. gonorrhoeae, particularly ceftriaxone resistance, has greatly complicated the treatment of gonorrhea, with the gonococcus now being classified as a "superbug".[7]

International Pathogenic Neisseria Conference

The International Pathogenic Neisseria Conference (IPNC), occurring every two years, is a forum for the presentation of cutting-edge research on all aspects of the genus Neisseria. This includes immunology, vaccinology, and physiology and metabolism of N. meningitidis, N. gonorrhoeae and the commensal species. The first IPNC took place in 1978, and the most recent one was in September 2008. Normally, the location of the conference switches between North America and Europe, but it took place in Australia for the first time in 2006, where the venue was located in Cairns, Australia.

References

- ↑ Ryan KJ; Ray CG (editors) (2004). Sherris Medical Microbiology (4th ed.). McGraw Hill. ISBN 0-8385-8529-9.

- ↑ http://www.meningitis.org/assets/x/53954

- ↑ Tronel H, Chaudemanche H, Pechier N, Doutrelant L, Hoen B (May 2001). "Endocarditis due to Neisseria mucosa after tongue piercing". Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 7 (5): 275–6. doi:10.1046/j.1469-0691.2001.00241.x. PMID 11422256.

- ↑ Ullrich, M (editor) (2009). Bacterial Polysaccharides: Current Innovations and Future Trends. Caister Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-904455-45-5.

- ↑ Seib KL, Rappuoli, R (2010). "Difficulty in Developing a Neisserial Vaccine". Neisseria: Molecular Mechanisms of Pathogenesis. Caister Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-904455-51-6.

- ↑ Shafer WM et al. (2010). "Molecular Mechanisms of Antibiotic Resistance Expressed by the Pathogenic Neisseria". Neisseria: Molecular Mechanisms of Pathogenesis. Caister Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-904455-51-6.

- ↑ Unemo M, Nicholas RA (December 2012). "Emergence of multidrug-resistant, extensively drug-resistant and untreatable gonorrhea". Future Microbiol. 7 (12): 1401–1422. doi:10.2217/fmb.12.117. PMC 3629839. PMID 23231489.