Necrotizing enterocolitis

| Necrotizing enterocolitis | |

|---|---|

Radiograph of an infant with necrotizing enterocolitis | |

| Classification and external resources | |

| ICD-10 | P77 |

| ICD-9 | 777.5 |

| DiseasesDB | 31774 |

| MedlinePlus | 001148 |

| eMedicine | ped/2981 radio/469 |

| MeSH | D020345 |

Necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) is a medical condition primarily seen in premature infants,[1] where portions of the bowel undergo necrosis (tissue death). It occurs postnatally (i.e. it is not seen in stillborn infants)[2] and is the second most common cause of mortality in premature infants,[3] causing 386 deaths in the United States in 2011, down from 472 in 2010.[4]

Signs and symptoms

The condition is typically seen in premature infants, and the timing of its onset is generally inversely proportional to the gestational age of the baby at birth (i.e. the earlier a baby is born, the later signs of NEC are typically seen).[5] Initial symptoms include feeding intolerance, increased gastric residuals, abdominal distension and bloody stools. Symptoms may progress rapidly to abdominal discoloration with intestinal perforation and peritonitis and systemic hypotension requiring intensive medical support.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis is usually suspected clinically but often requires the aid of diagnostic imaging modalities, most commonly radiography. Specific radiographic signs of NEC are associated with specific Bell's stages of the disease:[2]

Bell's stage 1/Suspected disease:

- Mild systemic disease (apnoea, bradycardia, temperature instability)

- Mild intestinal signs (abdominal distention, gastric residuals, bloody stools)

- Non-specific or normal radiological signs

Bell's stage 2/Definite disease:

- Mild to moderate systemic signs

- Additional intestinal signs (absent bowel sounds, abdominal tenderness)

- Specific radiologic signs (pneumatosis intestinalis or portal venous air)

- Laboratory changes (metabolic acidosis, thrombocytopaenia)

Bell's stage 3/Advanced disease:

- Severe systemic illness (hypotension)

- Additional intestinal signs (striking abdominal distention, peritonitis)

- Severe radiologic signs (pneumoperitoneum)

- Additional laboratory changes (metabolic and respiratory acidosis, disseminated intravascular coagulation)

More recently ultrasonography has proven to be useful as it may detect signs and complications of NEC before they are evident on radiographs, specifically in cases that involve a paucity of bowel gas, a gasless abdomen, or a sentinel loop.[6] Diagnosis is ultimately made in 5–10% of very low-birth-weight infants (<1,500g).[7]

Treatment

Treatment consists primarily of supportive care including providing bowel rest by stopping enteral feeds, gastric decompression with intermittent suction, fluid repletion to correct electrolyte abnormalities and third-space losses, support for blood pressure, parenteral nutrition,[8] and prompt antibiotic therapy. Monitoring is clinical, although serial supine and right lateral decubitus abdominal roentgenograms should be performed every six hours. Where the disease is not halted through medical treatment alone, or when the bowel perforates, immediate emergency surgery to resect the dead bowel is generally required, although abdominal drains may be placed in very unstable infants as a temporizing measure. Surgery may require a colostomy, which may be able to be reversed at a later time. Some children may suffer from short bowel syndrome if extensive portions of the bowel had to be removed.

Prevention

Once a child is born prematurely, thought must be given to decreasing the risk for developing NEC. Toward that aim, the methods of providing hyperalimentation and oral feeds are both important. In a 2012 policy statement, the American Academy of Pediatrics recommended feeding preterm infants human milk, finding "significant short- and long-term beneficial effects," including reducing the rate of NEC by a factor of two or more. [9]

A study by researchers in Peoria, IL, published in Pediatrics in 2008, demonstrated that using a higher rate of lipid (fats and/or oils) infusion for very low birth weight infants in the first week of life resulted in zero infants developing NEC in the experimental group, compared with 14% with NEC in the control group. (They started the experimental group at 2 g/kg/d of 20% IVFE and increased within two days to 3 g/kg/d; Amino acids were started at 3 g/kg/d and increased to 3.5.)[10]

Neonatologists at the University of Iowa reported on the importance of providing small amounts of trophic oral feeds of human milk starting as soon as possible, while the infant is being primarily fed intravenously, in order to prime the immature gut to mature and become ready to receive greater oral intake.[11] Human milk from a milk bank or donor can be used if mother's milk is unavailable. The gut mucosal cells do not get enough nourishment from arterial blood supply to stay healthy, especially in very premature infants, where the blood supply is limited due to immature development of the capillaries, so nutrients from the lumen of the gut are needed.

A Cochrane review published in April 2014 has established that supplementation of probiotics enterally prevents severe NEC as well as all-cause mortality in preterm infants."[12]

Increasing amounts of milk by 30 to 35 ml/kg is safe in infant who are born weighting very little or are premature.[13] Not beginning feeding an infant by mouth for more than 4 days does not appear to have protective benefits.[14]

Prognosis

Typical recovery from NEC if medical, non-surgical treatment succeeds, includes 10–14 days or more without oral intake and then demonstrated ability to resume feedings and gain weight. Recovery from NEC alone may be compromised by co-morbid conditions that frequently accompany prematurity. Long-term complications of medical NEC include bowel obstruction and anemia.

Despite a significant mortality risk, long-term prognosis for infants undergoing NEC surgery is improving, with survival rates of 70–80%. "Surgical NEC" survivors are at-risk for complications including short bowel syndrome and neurodevelopmental disability.

References

- ↑ Sodhi C, Richardson W, Gribar S, Hackam DJ (2008). "The development of animal models for the study of necrotizing enterocolitis". Dis Model Mech 1 (2-3): 94–8. doi:10.1242/dmm.000315. PMC 2562191. PMID 19048070.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Lin PW, Stoll BJ. Necrotising enterocolitis. Lancet. 2006 Oct 7;368(9543):1271–83.

- ↑ Panigrahi, P (2006). "Necrotizing enterocolitis: a practical guide to its prevention and management.". Paediatric drugs 8 (3): 151–65. doi:10.2165/00148581-200608030-00002. PMID 16774295.

- ↑ Hoyert, Donna L.; Jiaquan Xu (October 2012). "Deaths: Preliminary Data for 2011" (PDF). National Vital Statistics Reports 61 (6): 24.

- ↑ Yee, Wendy H.; Soraisham, Amuchou Singh; Shah, Vibhuti S.; Aziz, Khalid; Yoon, Woojin; Lee, Shoo K.; Canadian Neonatal Network (1 February 2012). "Incidence and Timing of Presentation of Necrotizing Enterocolitis in Preterm Infants". Pediatrics 129: e298–e304. doi:10.1542/peds.2011-2022. Retrieved 2013-07-25.

- ↑ Muchantef K, Epelman M, Darge K, Kirpalani H, Laje P, Anupindi SA. Sonographic and radiographic imaging features of the neonate with necrotizing enterocolitis: correlating findings with outcomes. Pediatr Radiol. 2013 Jun 15.

- ↑ Marino, Bradley S.; Fine, Katie S. (1 December 2008). Blueprints Pediatrics. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 978-0-7817-8251-7.

- ↑ Heird, WC; Gomez, MR (June 1994). "Total parenteral nutrition in necrotizing enterocolitis.". Clinics in perinatology 21 (2): 389–409. PMID 8070233.

- ↑ American Academy of Pediatrics, Section on Breastfeeding (2012). "Breastfeeding and the Use of Human Milk". Pediatrics 129 (3): e827–e841. doi:10.1542/peds.2011-3552. PMID 22371471. Retrieved 2013-07-25.

Meta-analyses of 4 randomized clinical trials performed over the period 1983 to 2005 support the conclusion that feeding preterm infants human milk is associated with a significant reduction (58%) in the incidence of NEC. A more recent study of preterm infants fed an exclusive human milk diet compared with those fed human milk supplemented with cow-milk-based infant formula products noted a 77% reduction in NEC.

- ↑ Drenckpohl D, McConnell C, Gaffney S, Niehaus M, Macwan KS (October 2008). "Randomized trial of very low birth weight infants receiving higher rates of infusion of intravenous fat emulsions during the first week of life". Pediatrics 122 (4): 743–51. doi:10.1542/peds.2007-2282. PMID 18829797.

- ↑ Ziegler EE, Carlson SJ (March 2009). "Early nutrition of very low birth weight infants". J. Matern. Fetal. Neonatal. Med. 22 (3): 191–7. doi:10.1080/14767050802630169. PMID 19330702.

- ↑ AlFaleh K, Anabrees J (2014). "Probiotics for prevention of necrotizing enterocolitis in preterm infants". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (4): CD005496. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005496.pub4.

- ↑ Morgan, J; Young, L; McGuire, W (2 December 2014). "Slow advancement of enteral feed volumes to prevent necrotising enterocolitis in very low birth weight infants.". The Cochrane database of systematic reviews 12: CD001241. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001241.pub5. PMID 25452221.

- ↑ Morgan, J; Young, L; McGuire, W (1 December 2014). "Delayed introduction of progressive enteral feeds to prevent necrotising enterocolitis in very low birth weight infants.". The Cochrane database of systematic reviews 12: CD001970. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001970.pub5. PMID 25436902.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

External links

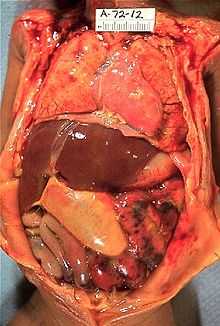

- Pictures of Necrotizing Enterocolitis at MedPix