Nazi gold

Nazi gold (German: Raubgold, "stolen gold") is the gold transferred by Nazi Germany to overseas banks during World War II. The regime executed a policy of looting the assets of its victims to finance the war, collecting the looted assets in central depositories. The occasional transfer of gold in return for currency took place in collusion with many individual collaborative institutions. The precise identities of those institutions, as well as the exact extent of the transactions, remain unclear.

The present whereabouts of Nazi gold that disappeared into European banking institutions in 1945 has been the subject of several books, conspiracy theories, and a failed civil suit brought in January 2000 against the Vatican Bank, the Franciscan Order, and other defendants.

Acquisition

The draining of Germany's gold and foreign exchange reserves inhibited the acquisition of materiel, and the Nazi economy, focused on militarisation, could not afford to deplete the means to procure foreign machinery and parts. Nonetheless, towards the end of the 1930s, Germany's foreign reserves were unsustainably low. By 1939, Germany had defaulted upon its foreign loans and most of its trade relied upon command economy barter.[1]

However, this tendency towards autarkic conservation of foreign reserves concealed a trend of expanding official reserves, which occurred through looting assets from annexed Austria, occupied Czechoslovakia, and Nazi-governed Danzig.[2] It is believed that these three sources boosted German official gold reserves by US $71m between 1937 and 1939.[2] To mask the acquisition, the Reichsbank understated its official reserves in 1939 by $40m relative to the Bank of England's estimates.[2]

During the war, Nazi Germany continued the practice on a much larger scale. Germany expropriated some $550m in gold from foreign governments, including $223m from Belgium and $193m from the Netherlands.[2] These figures do not include gold and other instruments stolen from private citizens or companies. The total value of all assets stolen by Nazi Germany remains uncertain.

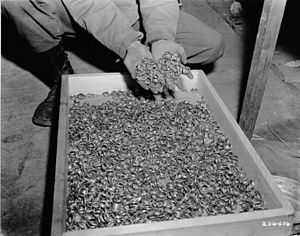

A growing source of precious metal came from Nazi concentration camps and death camps, where all property was taken from the victims, and included personal effects such as wedding rings, eye glasses, pocket watches, cigarette cases, jewellery and gold teeth. (All other substantial property, such as houses, paintings, shares, and bonds, were stolen from the victims before they entered the camps.) The gold was collected at the camps and sent to the Reichsbank under the false-name Max Heiliger accounts for melting down for bullion.

Much of the gold bullion was stored in abandoned mines in Germany, such as the Merkers mine, where it was found by US soldiers towards the end of the war in 1945. Other resources such as the personal possessions of the victims of Nazi persecution, were found in the concentration camps on liberation.

Discovery, Merkers Mine

Advancing north from Frankfurt, the US 3rd Army cut into the future Soviet zone when it occupied the western tip of Thuringia. On 4 April, the 90th Infantry Division took Merkers, a few miles inside the border in Thuringia. On the morning of the 6th, two military policemen, Pfc. Clyde Harmon and Pfc. Anthony Kline, enforcing the customary orders against civilian circulation, stopped two women on a road outside Merkers. Since both were French displaced persons and one was pregnant, the MPs decided rather than to arrest them to escort them back into the town. On the way, as they passed the entrance to the Kaiseroda salt mine in Merkers, the women talked about gold that the Germans had stored in the mine – so much gold, they said, that unloading it had taken local civilians and displaced persons who were used as labor seventy-two hours. By noon the story had passed from the MP first sergeant to the chief of staff and on to the division's G-5 officer, Lt. Col. William A. Russell, who in a few hours had the news confirmed by other DPs and by a British sergeant who had been employed in the mine as a prisoner of war and had helped unload the gold. Russell also turned up an assistant director of the National Galleries in Berlin who admitted he was in Merkers to care for paintings stored in the mine. The gold was reportedly the entire reserve of the Reichsbank in Berlin, which had moved it to the mine after the bank building was bombed out in February 1945. When Russell learned that the mine had thirty miles of galleries and five entrances, the division, which had already detailed the 712th Tank Battalion to guard the Merkers entrance, had to divert the whole 357th Infantry Regiment to guard the other four.

The next morning, after having steam raised in the boilers overnight to generate electricity for the lifts and ventilators, Russell went down into the mine with a party of division officers, German mine officials, and Signal Corps photographers. Near the entrance to the main passageway they found 550 bags containing a half billion in paper Reichsmarks. A steel vault door on the entrance to the tunnel said to contain the gold was locked. In the afternoon, after having tried unsuccessfully to open the door, the party left the mine without having seen the treasure.

The next day was Sunday. In the morning, while Colonel Bernard D. Bernstein, Deputy Chief, Financial Branch, G-5, SHAEF, read about the find[3] in the Stars and Stripes's Paris edition,[4] 90th Infantry Division engineers blasted a hole in the vault wall to reveal on the other side a room 75 feet wide and 150 feet deep. The floor was covered with rows of numbered bags, over 7,000 in all, each containing gold bars or gold coins. Baled paper money was stacked along one wall; and at the back, a mute reminder of Nazism's victims, valises were piled filled with gold and silver tooth fillings, eyeglass frames, watch cases, wedding rings, pearls, and precious stones. The gold, between 55 and 81 pounds to the bag, amounted to nearly 250 tons. In paper money, all the European currencies were represented. The largest amounts were 98 million French francs and 2.7 billion Reichsmarks. The treasure almost made the 400 tons of art work, the best pieces from the Berlin museums, stacked in the mine's other passages seem like a routine find.

On Sunday afternoon, Bernstein, after verifying to the fullest the newspaper story with Lt. Col. R. Tupper Barrett, Chief, Financial Branch, G-5, 12th Army Group, flew to SHAEF Forward at Rheims where he spent the night, it being too late by then to fly into Germany. At noon on Monday, he arrived at Gen. George S. Patton's Third Army Headquarters with instructions from Eisenhower to check the contents of the mine and arrange to have the treasure taken away. While he was there, orders arrived for him to locate a depository farther back in the SHAEF zone and supervise the moving. Bernstein and Barrett spent Tuesday looking for a site and finally settled on the Reichsbank building in Frankfurt. Wednesday, at Merkers, they planned the move and prepared for distinguished visitors by having Germans tune up the mine machinery. The next morning, Generals Eisenhower, Bradley, Patton, and Maj. Gen. Manton S. Eddy took the 1,600-foot ride down into the mine. When they stepped out at the foot of the shaft, the private on guard saluted and, in the underground stillness, was heard by all to mutter, "Jesus Christ !"

The move began at 0900 on Saturday morning, 14 April. In twenty hours, the gold and currency and a few cases of art work were loaded on thirty ten-ton trucks, each with a 10 percent overload. Down in the mine, jeeps with trailers hauled the treasure from the vault to the shaft, where the loaded trailers were put aboard the lifts and brought to the surface. At the vault entrance an officer registered each bag or item on a load slip, and at the truck ramps an officer and an enlisted man checked the load slips and verified that every item that left the vault was loaded on a truck. Finally, the officer recorded the truck number and the names and serial numbers of the driver, the assistant driver, and the guards assigned to the truck.

The convoy left Merkers on Sunday morning for the 85-mile trip to Frankfurt with an escort of five rifle platoons, two machine gun platoons, ten multiple-mount antiaircraft vehicles, and Piper cub and fighter air cover. All this protection, however, was not enough to prevent a rumor, which surfaced periodically for years after, that one truckload of gold (or art work) disappeared on the way to Frankfurt. On Sunday afternoon and throughout the night the trucks were unloaded in Frankfurt, each item being checked against the load lists as it came off a truck and again when it was moved into the Reichsbank vault. Two infantry companies cordoned off the area during the unloading.

The same procedures, except that a hundred German prisoners of war did the work, were followed in loading the art objects aboard a second truck convoy on Monday, and a similar security guard escorted the trucks to Frankfurt the next day. After the main treasure was removed, the mine was still a grab bag of valuables. Reconnaissance of the other entrances had turned up four hundred tons of German patent office records, Luftwaffe material and ammunition, German Army High Command records, libraries and city archives (including 2 million books from Berlin and the Goethe collection from Weimar), and the files of the Krupp, Henschel, and other companies. The patent records in particular were potentially as valuable as the gold; but Third Army needed its trucks, and Bernstein had to settle, on 21 April, for a small seven-truck convoy to move the cream of the patent records, samples of the Krupp and Henschel files, and several dozen high quality microscopes.

Leads found in the Reichsbank records at Merkers also helped uncover a dozen other treasure caches in places occupied by US forces that brought into the vault in Frankfurt hundreds more gold and silver bars, some platinum, rhodium, and palladium, a quarter of a million in US gold dollars (the Merkers mine set the record, however, containing 711 bags of US $20 gold pieces, $25,000 to the bag), a million Swiss old francs, and a billion French francs.

Disposal

The present whereabouts of the Nazi gold that disappeared into European banking institutions in 1945 has been the subject of several books, conspiracy theories, and a civil suit brought in January 2000 in California against the Vatican Bank, the Franciscan Order and other defendants.[5] The suit against the Vatican Bank did not claim that the gold was then in its possession and has since been dismissed.[6][7]

The Swiss National Bank, the largest gold distribution centre in continental Europe before the war, was the logical venue through which Nazi Germany could dispose of its gold.[8] During the war, the SNB received $440m in gold from Nazi sources, of which $316m is estimated to have been looted.[9]

Vatican

On October 21, 1946, the U.S. State Department received a Top Secret report from US Treasury Agent Emerson Bigelow.[10][11] The report established that Bigelow received reliable information on the matter from the American Office of Strategic Services (OSS) or CIC intelligence officials of the US Army.[12] The document, referred to as the "Bigelow Report", was declassified on December 31, 1996, and released in 1997.

The report asserted that in 1945, the Vatican had confiscated 350 million Swiss francs in Nazi gold for "safekeeping," of which 150 million Swiss francs had been impounded by British authorities at the Austro-Swiss border. The report also stated that the balance of the gold was held in one of the Vatican’s numbered Swiss bank accounts. Intelligence reports, which corroborated the Bigelow Report, also suggested that more than 200 million Swiss francs, a sum largely in gold coins, were eventually transferred to Vatican City or to the Institute for Works of Religion (aka the Vatican Bank), with the assistance of Roman Catholic clergy and the Franciscan Order.[13][14][15]

Such claims, however, are denied by the Vatican Bank. "There is no basis in reality to the [Bigelow] report", said Vatican spokesman Joaquin Navarro-Valls, as reported in Time magazine.[16]

Portugal

During the war, Portugal, with neutral status, was one of the centres of tungsten production and sold to both Allied and Axis powers. Tungsten is a critical metal for armaments, especially for armour-piercing bullets and shells. Much of the Axis tungsten was purchased with Nazi gold bullion, which was looted from the countries they had invaded as well as their dead victims. It is estimated that nearly 100 tons of Nazi gold were laundered through Swiss banks, with only four tons being returned at the end of the war.[17]

During the war, Portugal was the second largest recipient of Nazi gold, after Switzerland; this came through the sale of tungsten, with the German armaments industry nearly entirely dependent on the supplies from Portugal.[18] Initially the Nazi trade with Portugal was in hard currency, but in 1941 the central Bank of Portugal established that much of this was counterfeit and Portuguese leader António de Oliveira Salazar demanded all further payments in gold.[19] Presumably the counterfeit currency were the infamous banknotes produced by Sachsenhausen concentration camp victims in Operation Bernhard.

See also

- 2012 Munich artworks discovery

- August Frank memorandum

- Chiemsee Cauldron

- Gold laundering

- Lake Toplitz

- List of missing treasure

- Moscow gold

- Montagu Norman

- Nazi loot

- Tripartite Commission for the Restitution of Monetary Gold

Notes

- ↑ Medlicott, William (1978). The Economic Blockade (Revised edition ed.). London: HMSO. pp. 25–36.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 UK Treasury correspondence, T 236/931.

- ↑ McKinzie, Richard D. (23 July 1975). "Oral History Interview with Bernard Bernstein". New York, New York: Harry S. Truman Library. Retrieved 11 November 2012.

- ↑ Stars and Stripes, Paris edition, printed at the New York Herald Tribune plant | http://www.wartimepress.com/archives.asp?TID=Paris&MID=Stars%20and%20Stripes%20-%20All%20Editions&q=168&FID=10

- ↑ Text of the Civil Action of January 21, 2000: Factual Allegations, nos. 25 – 38.

- ↑ "United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit" (PDF). Retrieved 2014-07-28.

- ↑ "Slovodna Dalmacija". Slobodnadalmacija.hr. Retrieved 2014-07-28.

- ↑ Eizenstat Special Briefing on Nazi Gold. Stuart Eizenstat, US State Department, 2 June 1998. Retrieved on 5 July 2006.

- ↑ "Switzerland and Gold Transactions in the Second World War" PDF (1.18 MB). Bergier Commission, May 1998. Retrieved on 5 July 2006.

- ↑ "CNN:"Vatican drawn into scandal over Nazi-era gold"". July 22, 1997.

- ↑ "Inquiry Into Vatican Link to Looted Gold," The Guardian, July 23, 1997, p. 11

- ↑ Aarons, Mark; Loftus, John (1992). Unholy Trinity: How the Vatican's Nazi Networks Betrayed Western Intelligence to the Soviets (revised, 1993 ed.). New York: St.Martin's Press. p. 297. ISBN 0-312-09407-8.

- ↑ Paris, Edmond; Perkins, Lois (1961). Genocide in Satellite Croatia 1941-1945: A Record of Racial and Religious Persecutions and Massacres (reissued, 1990 ed.). The American Institute for Balkan Affairs. p. 306. ASIN B0007DWXR8

- ↑ Aarons, Mark; Loftus, John (1993). Unholy Trinity: How the Vatican's Nazi Networks Betrayed Western Intelligence to the Soviets (Revised Edition ed.). New York: St.Martin's Press. pp. (432 pages). ISBN 0-312-09407-8.

- ↑ Manhattan, Avro (1986). The Vatican's Holocaust: The Sensational Account of the Most Horrifying Religious Massacre of the 20th Century (1988, paperback edition ed.). Ozark Books. pp. 237 total. ASIN B000KOOLWE

- ↑ "The Vatican Pipeline by Frank Pellegrini". Time. July 22, 1997.

- ↑ Simons, Marlise (10 January 1997). "Nazi Gold and Portugal's Murky Role". New York Times. Retrieved 1 June 2011.

- ↑ Gonçalves, Eduardo (2 April 2000). "Britain allowed Portugal to keep Nazi gold". The Observer. Retrieved 6 June 2011.

- ↑ Lochery, Neill (17 May 2011). "Portugal's Golden Dilemma". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 6 June 2011.

References

- Alford, Kenneth D.; Savas, Theodore P. (2002). Nazi Millionaires: The Allied Search for Hidden SS Gold (1st ed.). Casemate Publishers and Book Distributors. ISBN 0-9711709-6-7.

- Wechsberg, Joseph; Wiesenthal, Simon (1967). The Murderers Among Us: The Simon Wiesenthal Memoirs. New York: McGraw-Hill. p. 335. LCN 67-13204. ASIN B000OL6LK8

- Infield, Glenn (1981). The Secrets of the SS (reissued, 1994 ed.). New York: Stein and Day. p. 288. ISBN 0-515-10246-6.

- Aarons, Mark; Loftus, John (1992). Unholy Trinity: How the Vatican's Nazi Networks Betrayed Western Intelligence to the Soviets (revised, 1993 ed.). New York: St.Martin's Press. p. 297. ISBN 0-312-09407-8.

- Paris, Edmond; Perkins, Lois (1961). Genocide in Satellite Croatia 1941-1945: A Record of Racial and Religious Persecutions and Massacres (reissued, 1990 ed.). The American Institute for Balkan Affairs. p. 306. ASIN B0007DWXR8

- Manhattan, Avro (1986). The Vatican's Holocaust: The Sensational Account of the Most Horrifying Religious Massacre of the 20th Century (1988, paperback edition ed.). Ozark Books. pp. 237 total. ASIN B000KOOLWE

- Sayer, Ian (1984). Nazi Gold: The Story of the World's Greatest Robbery - And Its Aftermath (co-author Douglas Botting with the London Sunday Times). Granada. ISBN 0-246-11767-2.

- Yeadon, Glen (2008). The Nazi Hydra in America. Progressive Press. p. 700. ISBN 0-930852-43-5.

External links

- Nazi Gold and Art -- from Hitler's Third Reich and World War II in the News

- Swiss gold holdings and transactions during WW2

- PBS Frontline: Nazi Gold

- Report of the Swiss Bergier Commission

- Nazi Gold Report (Stuart Eizenstat, Under Secretary for Economic, Business, and Agricultural Affairs, on-the-record briefing upon release of U.S. and Allied Wartime and Postwar Relations and Negotiations With Argentina, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, and Turkey on Looted Gold and German External Assets and U.S. Concerns About the Fate of the Wartime Ustasha Treasury, Washington, DC, June 2, 1998)

- (U.S. News & World Report) "A vow of silence. Did gold stolen by Croatian fascists reach the Vatican?" 30n March 1998

- Lawsuit against Vatican Bank to recover Second World War era gold

- Law-Related Resources on Nazi Gold and Other Holocaust Assets, Swiss Banks during World War II, and Dormant Accounts

- Nazi Gold: The Merkers Mine Treasure

- Bank of England role in selling Nazi gold looted from Czechoslovakia