Remarks from 1937 by FDR on "natural capital" and "balancing the budget of our resources"

Natural capital is the world's stock of natural resources which creates a long term supply of goods or services. It is an extension of the economic notion of capital (resources which enable the production of more resources) to goods and services provided by the natural environment. For example, a forest or river may provide an indefinitely sustainable flow of new trees or fish. Natural capital may also provide essential services like water catchment and erosion control, which ensure the long term viability of natural resources. Since the maintenance of natural capital requires the preservation of cohesive ecosystems, the structure and diversity of the system are important to ensure the long term sustainability of the resources generated.[1]

History of the concept

Natural capital is one approach to ecosystem valuation which revolves around the idea, in contrast to traditional economics, that non-human life produces essential resources. Thus, ecological health is essential to the sustainability of the economy. In Natural Capitalism: Creating the Next Industrial Revolution[2] the author claims that the global economy is within a larger economy of natural resources and ecosystem services that sustain us. In order to continue to reap the benefits of our natural environment, we need to recognize the importance of natural capital within the economy. According to the authors, the "next industrial revolution" depends on the espousal of four central strategies: "the conservation of resources through more effective manufacturing processes, the reuse of materials as found in natural systems, a change in values from quantity to quality, and investing in natural capital, or restoring and sustaining natural resources."[3]

In a traditional economic analysis of the factors of production, natural capital would usually be classified as "land" distinct from traditional "capital". The historical distinction between "land" and "capital" defined “land” as naturally occurring with a fixed supply, whereas “capital”, as originally defined referred only to man-made goods. (e.g., Georgism[4][5]) It is however, misleading to view "land" as if its productive capacity is fixed, because natural capital can be improved or degraded by the actions of man over time (see Tragedy of the Commons). Moreover, natural capital yields benefits and goods, such as timber or food, which can be harvested by humans. These benefits are similar to those realized by owners of infrastructural capital which yields more goods, such as a factory which produces automobiles just as an apple tree produces apples.

The term 'natural capital' was first used by in 1973 by E.F. Schumacher in his book Small Is Beautiful[6] and is closely identified with Herman Daly, Robert Costanza, the Biosphere 2 project, and the Natural Capitalism economic model of Paul Hawken, Amory Lovins, and Hunter Lovins. Recently, it has begun to be used by politicians, notably Ralph Nader, Paul Martin Jr., and agencies of the UK government, including the London Health Observatory. All users of the term currently differentiate natural from man-made manufactured or infrastructural capital in some way. Indicators adopted by United Nations Environment Programme's World Conservation Monitoring Centre and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) to measure natural biodiversity use the term in a slightly more specific way. According to the OECD, natural capital is “natural assets in their role of providing natural resource inputs and environmental services for economic production” and is “generally considered to comprise three principal categories: natural resources stocks, land, and ecosystems.”

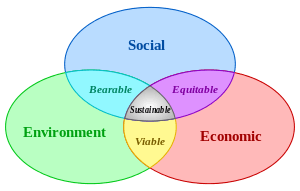

Within the international community, the basic principle is not controversial, but there is significant controversy over methods of valuing different aspects of ecological health and natural capital. Full cost accounting, triple bottom line, measuring well-being and other proposals for accounting reform often include proposals to measure an "ecological deficit" or "natural deficit" alongside a social deficit and financial deficit. It is difficult to measure such a deficit without some agreement on methods of valuating and auditing at least the global forms of natural capital (e.g. value of air, water, soil).

Ecologists are teaming up with economists to measure and express values of the wealth of ecosystems as a way of finding solutions to the biodiversity crisis.[7][8][9] Some researchers have attempted to place a dollar figure on ecosystem services such as the value that the Canadian boreal forest's contribution to global ecosystem services. If ecologically intact, the boreal forest has an estimated value of US$3.7 trillion. The boreal forest ecosystem is one of the planet's great atmospheric regulators and it stores more carbon than any other biome on the planet.[10] The annual value for ecological services of the Boreal Forest is estimated at US$93.2 billion, or 2.5 greater than the annual value of resource extraction. The economic value of 17 ecosystem services for the entire biosphere (calculated in 1997) has an estimated average value of US$33 trillion per year.[11] These ecological economic values are not currently included in calculations of national income accounts, the GDP and they have no price attributes because they exist mostly outside of the global markets.[12][13] The loss of natural capital continues to accelerate and goes undetected or ignored by mainstream monetary analysis.[14]

Internationally agreed standard

Environmental-economic accounts provide the conceptual framework for integrated statistics on the environment and its relationship with the economy, including the impacts of the economy on the environment and the contribution of the environment to the economy. A coherent set of indicators and descriptive statistics can be derived from the accounts that inform a wide range of policies, including, but not limited to, green economy/green growth, natural resource management and sustainable development. The System of Environmental-Economic Accounting (SEEA) contains the internationally agreed standard concepts, definitions, classifications, accounting rules and tables for producing internationally comparable statistics on the environment and its relationship with the economy. The SEEA is a flexible system in the sense that its implementation can be adapted to countries' specific situations and priorities. Coordination of the implementation of the SEEA and on-going work on new methodological developments is managed and supervised by the UN Committee of Experts on Environmental-Economic Accounting (UNCEEA). The final, official version of the SEEA Central Framework was published in February 2014.

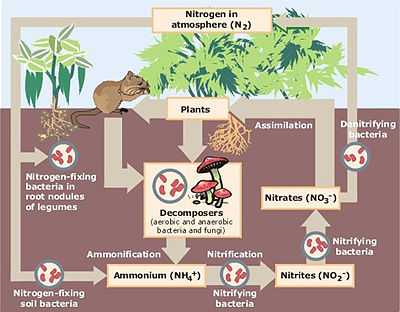

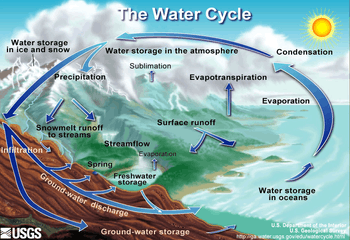

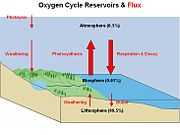

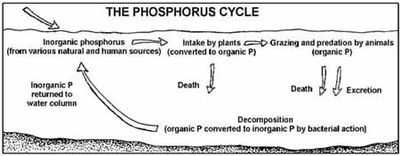

| Global biogeochemical cycles critical for life |

|---|

|

See also

References

Notes

- ↑ Encyclopedia of Earth

- ↑ Hawken, Paul; Amory Lovins; Hunter Lovins (1999). Natural Capitalism: Creating the Next Industrial Revolution.

- ↑ Book Review: Natural Capitalism from Socialfunds.com. Retrieved April 2009.

- ↑ - Progress and Poverty by Henry George, Chapter 2.

- ↑ http://www.henrygeorge.org/def2.htm

- ↑ Schumacher, E.F (1973). Small is Beautiful: A Study of Economics As If People Mattered.

- ↑ Edwards, P. J.; Abivardi, C. (1998). "The value of biodiversity: Where ecology and economy blend". Biological Conservation 83 (2): 239–246. doi:10.1016/S0006-3207(97)00141-9.

- ↑ Naidoo, R.; Malcolm, T.; Tomasek, A. (2009). "Economic benefits of standing forests in highland areas of Borneo: quantification and policy impacts" (PDF). Conservation Letters 2: 35–44.

- ↑ Zhoua, X.; Al-Kaisib, M.; Helmers, M. J. (2009). "Cost effectiveness of conservation practices in controlling water erosion in Iowa". Soil and Tillage Research 106 (1): 71–8. doi:10.1016/j.still.2009.09.015.

- ↑ Jonsson, M.; Wardle, D. A. (2009). "Structural equation modelling reveals plant-community drivers of carbon storage in boreal forest ecosystems". Biology Letters 6 (1): 1–4. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2009.0613. PMC 2817262. PMID 19755530. Retrieved Downloaded from rsbl.royalsocietypublishing.org on January 13, 2010.

- ↑ Costanza, R. et al. (1997). "The value of the world’s ecosystem services and natural capital." (PDF). Nature 387 (6630): 253–260. doi:10.1038/387253a0.

- ↑ Ferguson, K. (2006). "The True Value of Forests". Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 4 (9): 456.

- ↑ Anielski, M.; Wilson, S. (2005). "Counting Canada’s Natural Capital: Assessing the Real value of Canada’s Boreal Ecosystems" (PDF). Can. Bor. Ini., Pembina Institute, Ottawa.

- ↑ Wakernagel, M.; Rees, W. E. (1997). "Perceptual and structural barriers to investing in natural capital: Economics from an ecological footprint perspective.". Ecological Economics 20 (1): 3–24. doi:10.1016/S0921-8009(96)00077-8.

Further reading

- Pearce, D. 1993. Blueprint 3: Measuring Sustainable Development. Earthscan. ISBN 1-85383-183-2

- Jansson, AnnMari; et al. (1994). Investing in Natural Capital : The Ecological Economics Approach to Sustainability. Washington, D.C.: Island Press, 504 pp. ISBN 1-55963-316-6.

- Daily, Gretchen C. (editor) (1997). Nature’s Services: Societal Dependence on Natural Ecosystems. Washington, D.C.: Island Press, 392 pp. ISBN 1-55963-476-6.

- Prugh, Thomas; Robert Costanza et al. (1999). Natural capital and human economic survival. Solomons, Md.: International Society for Ecological Economics, 180 pp. ISBN 1-56670-398-0.

External links

|

|---|

| | | | By term | |

|---|

| | Marxist analytical | |

|---|

| | Marxist historical | |

|---|

|

|

|---|

| | Air | | |

|---|

| | Energy | |

|---|

| | Land | |

|---|

| | Life | |

|---|

| | Water | |

|---|

| | Related | |

|---|

|  Portals Portals |

- Agriculture and Agronomy

- Energy

- Environment

- Fishing

- Forestry

- Mining

- Water

|

|---|

| |

|