National colours of Italy

The national colours of Italy are green, white, and red,[1] collectively known in Italian as il tricolore (the tricolour). In sport in Italy, azure has been used or adopted as the colour for many national teams, the first being the men's football team in 1910.

Revolution

The tricolore was symbolically important preceding and throughout the Risorgimento leading to Italian unification. In September 1794, Luigi Zamboni and Giambattista de Rolandis created a flag by uniting the white and red of the flag of Bologna with green, a symbol of liberty and hope that the populace of Italy join the revolution begun in Bologna to oust the foreign occupying forces.[2][3] This tricolore was considered a symbol of redemption that from its creation was "consecrated to immortality of the triumph of faith, virtue, and sacrifice" of those who created it.[4]

Napoleon Bonaparte, in a letter from Milan to an executive director on 11 October 1796, stated that the Legione Lombarda had chosen these colours as the national colours.[5] In a solemn ceremony at the Piazza del Duomo on 16 November 1796, a military flag was presented to the Legione Lombarda, which would become a unit in the Cisalpine Republic (1797–1802) military, and was the first tricolore military standard to fly at the head of an Italian military unit.[6][7] The first official Italian flag was created for the Cispadane Republic (1796–1797) in Reggio Emilia on 7 January 1797 based on a proposal by government deputy Giuseppe Compagnoni.[8][3]

The formation of the Cisalpine Republic was decreed by Napoleon on 29 June 1797, and consisted of most of the Cispadane Republic and Transpadane Republic (1796–1797), which included between them Milan, Mantua, the portion of Parma north of the Po river, Bologna, Ferrara, and Romagna, and later the Venetian Republic.[9] Its flag was proclaimed to be the tricolore, representing the "red and white of Bologna and the green of liberty".[10]

Young Italy, a political movement founded in 1831 by Giuseppe Mazzini calling for a national revolution to unify all Italian-speaking provinces, used a "theatrical" uniform based on the national colours.[11] These colours had been in use in the Cispadane Republic, Transpadane Republic, Cisalpine Republic, Italian Republic (1802–1805), and the Kingdom of Italy (1805–1814), precursors to the modern state. During the formation of the Roman Empire of 1814, the foundational constitutional basis specified that the three national colours would be preserved.[12]

Politics

The colours have been used for political purposes.

During his visit to London on 11 April 1864, Giuseppe Garibaldi was greeted by a throng of people at the train station, many of whom carried Italian flags.[13] English men dressed in red shirts commonly worn by Garibaldi's followers during his Mille expedition to southern Italy, and women dressed in the national colours of Italy.[13] Italian flags could be seen throughout the city.[13] In 1848, Garibaldi's legion dressed in red shirts with green and white facing.[14]

In 1868, two years after the Austrians departed Venice following the Third Italian War of Independence, the remains of statesman Daniele Manin were brought to his native city and honoured with a public funeral.[15] He had been acclaimed president of the Venetian Republic of San Marco by residents of Venice after a revolt in 1848.[16][17] The gondola carrying his coffin was decorated with bow "surmounted by the lion of Saint Mark, resplendent with gold", bore "the Venetian standard veiled with black crape", and had "two silver colossal statues waving the national colours of Italy".[18] The statues represented the unification of Italy and Venice.[19] The funeral procession was described as "magnificent".[19] His remains are interred at the Basilica of Santa Croce, the first person buried there in over 300 years.[15]

An apocryphal story about the history of pizza holds that on 11 June 1889, Neapolitan pizzamaker Raffaele Esposito created a pizza to honour Margherita of Savoy, who was visiting the city. It was garnished with tomatoes, mozzarella, and basil to represent the national colours of Italy, and was named "Pizza Margherita".[20][21][22]

Definition

In 2003, the government of Italy specified the colours using Pantone. The new specification was demonstrated on sample flags displayed at Palazzo Montecitorio; they had a darker tint than the traditional colours, described as having a deeper green, a red with "ruby hues", and ivory or cream instead of white.[23][24] Alfonso Pecoraro Scanio, president of the Federation of the Greens and a member of the Chamber of Deputies, stated that Silvio Berlusconi had achieved a "chromatic coup d'etat".[23] Government officials stated that the sample flags did not conform to the "specified chromatic specification".[24] The values were revised after discussion, and in 2006 were decreed by law in Article 31 of Disposizioni generali in materia di cerimoniale e di precedenza tra le cariche pubbliche ("General provisions relating to ceremonial materials and precedence for public office", published 28 July 2006 in Gazzetta Ufficiale) for polyester fabric bunting to use the following Pantone Textile Colour System values:[25][26]

| Pantone Name | Pantone Number | RGB | CMYK | HSV | Hex | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fern Green | 17-6153 TC | 0-146-70 | 100-0-100-45 | 149-100-057 | #009246 | |

| Bright White | 11-0601 TC | 241-242-241 | 0-0-0-0 | 120-000-095 | #F1F2F1 | |

| Flame Scarlet | 18-1662 TC | 206-43-55 | 0-100-100-0 | 365-079-081 | #CE2B37 | |

Use

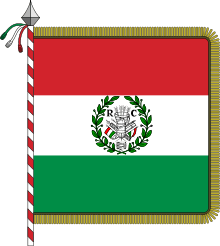

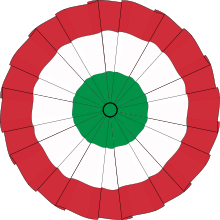

The national colours are specified in the Constitution of Italy to be used on the Flag of Italy, a vertical tricolour flag of green, white, and red.[27][28] It is also used on the cockade, another of the national symbols of Italy. Its use of the national colours was the antecedent for its use in the flag.[29][30][31]

The Presidential Standard of Italy is the flag used by the President of the Italian Republic, the nation's head of state. It is based on the square flag of the Napoleonic Italian Republic, on a field of blue charged with the coat of arms of Italy in gold.[32]

On 31 December 1996, legislation was passed (legge no. 671) instituting 7 January as national flag day, known as Festa del Tricolore, and was published in the Gazzetta Ufficiale della Repubblica Italiana three days later.[33] Its purpose was to celebrate the bicentennial of the establishment of the Italian flag on 7 January 1797.[3] The most important of these celebrations is that at the Sala del Tricolore ("Room of the tricolour") in the commune palace of Reggio Emilia, and a solemn changing of the guard at the Quirinal Palace in Rome, followed by a parade of the Corazzieri and a brass band fanfare by the Carabinieri Cavalry Regiment.[3]

Sport

In football, the winners of Serie A are the Italian football champions, which entitles the winning team to adorn the jersey of each of its players with the scudetto, an escutcheon (heater shield) of the Italian flag, the subsequent season.[34] The practice was established in 1924, after Gabriele D'Annunzio had wanted to put a shield flag on the uniforms of Italian military commanders during a friendly match.[34] The league operators state that it is "representative of national unity at the level of football".[34] The winner of the Coppa Italia is entitled to adorn its team jersey with a tricolour cockade for the subsequent season.[35]

After having played its first two international matches in white in 1910, the men's football team announced its new uniform on 31 December 1910, an azure shirt with an escutcheon of the Italian colours, and white shorts.[36] Widespread opinion was that the blue colour had been chosen as an homage to the House of Savoy that had previously ruled parts of northern Italy until the nation's unification.[36] The uniform was first worn on 6 January 1911 in a match against Hungary in Milan.[36]

In sport, many men's national teams are known as the azzurri and women's teams as the azzurre (meaning "azure"). These include the men's basketball,[37] men's football, men's ice hockey, men's rugby league, men's rugby union, and men's volleyball[38] teams, and the women's basketball,[39] women's football, women's ice hockey, and women's volleyball[40] teams.

The national auto racing colour of Italy is rosso corsa ("racing red").[41]

Other

The Frecce Tricolori, the aerobatics demonstration team of the Italian Aeronautica Militare based at Rivolto Air Force Base, are so named for the green, white, and red smoke trails emitted during performances, representing the national colours.[42][43]

The name of Italia Peak, a peak in the Elk Mountains of Colorado in the United States, is derived from the display on one of its faces, when seen at a distance, of "brilliant red, white and green colors, the national colors of Italy".[44][45][46]

Notes

- ↑ Ferorelli 1925, p. 654-680.

- ↑ Venosta 1864, p. 30-32Noi al bianco ed al rosso, colori della nostra Bologna, uniamo il verde, in segno della speranza che tutto il popolo italiano segua la rivoluzione nazionale da noi iniziata, che cancelli que' confini segnati dalla tirannide forestiera.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 La Repubblica 2013.

- ↑ Venosta 1864, p. 32.

- ↑ Bonaparte 1822, p. 238Vous y trouverez l'organisation de la légion lombarde. Les couleurs nationales qu'ils ont adoptées sont le vert, le blanc et le rouge.

- ↑ Frasca 2001, p. 49.

- ↑ Canella 2009, p. 130.

- ↑ Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

- ↑ Partington 1836, p. 548.

- ↑ Waley & Hearder 1963, p. 118.

- ↑ Collier 2003, p. 25The national colours of Italy were worn in combination with a green blouse being complemented with a red belt and white trousers.

- ↑ Dippel 2009, p. 25I tre colori nazionali sono conservati.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Oddo 1865, p. 522.

- ↑ Young & Stevens 1864, p. 64.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Cook Thomas and son 1874, p. 29.

- ↑ Cunsolo: Venice and the Revolution of 1848–49.

- ↑ Cunsolo: Daniele Manin (1804–1857).

- ↑ Cook Thomas and son 1874, p. 29–30.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Cook Thomas and son 1874, p. 30.

- ↑ Danford, p. 38.

- ↑ Philadelphia Enquirer 1989, p. E08.

- ↑ Lakeland Ledger 1989, p. 12A.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 BBC: Italian opposition in flap over flag.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Corriere della Sera 2003.

- ↑ Gazzetta Ufficiale della Repubblica Italiana 2006.

- ↑ Prefettura di Pisa, p. 2.

- ↑ La Costituzione.

- ↑ Constitution of the Italian Republic.

- ↑ Biblioteca dell'Accademia virgiliana, p. 4...o Bandiera Cispadana di tre colori, verde, bianco e rosso, e che questi tre colori si usino anche nella coccarda cispadana la quale debba portarsi da tutti

- ↑ Protonotari 1897, p. 239-267 and 676–710.

- ↑ Murati 1892, p. 12–13.

- ↑ & Gazzetta Ufficiale della Repubblica Italiana 2000.

- ↑ Gazzetta Ufficiale della Repubblica Italiana 1997.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 34.2 Lega Nazionale Professionisti: Premiazione scudetto 2012.

- ↑ Lega Nazionale Professionisti:Regolamento 2012, p. 247/700 and Articolo 1, section 12.1 Società vincitrice.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 36.2 Chiesa 2012, p. 44, chapter 1910–1912, Azzurri come il cieloSiamo informati che la squadra nazionale avra finalmente una sua propria divisa: una maglia di colore bleu marinaro, con sul petto uno scudo racchiudente i colori italiani

- ↑ Federazione Italiana Pallacanestro: Gli azzurri.

- ↑ Federazione Italiana Pallavolo: Azzurri.

- ↑ Federazione Italiana Pallacanestro: Le Azzurre.

- ↑ Federazione Italiana Pallavolo: Azzurre.

- ↑ Bristow 2013, p. 7.

- ↑ Haberman 1989.

- ↑ Wings, p. 6the Italians call themselves Frecce Tricolori (and emphasize the title by emitting red, white, and green smoke)

- ↑ Ayer 1880, p. 211.

- ↑ Diller 1902, p. 145.

- ↑ Dana & Silliman 1874, p. 400.

References

- Ayer, I. Winslow (1880). Life in the Wilds of America. Central Publishing Company.

- Bonaparte, Napoléon (1822). Panckoucke, C. L. F., ed. Oeuvres de Napoléon Bonaparte 1. Paris.

- Bristow, Grahame (2013). Restoring Sprites and Midgets. M-Y Books Distribution. ISBN 9781783180189.

- Canella, Maria, ed. (2009). Dalla Repubblica Cisalpina al Regno d'Italia (1797–1814) Ricerche e strumenti. Armi e nazione. FrancoAngeli. ISBN 8856809982.

- Chiesa, Carlo (2012). La grande storia del calcio italiano. Bologna: Guerin Sportivo.

- Collier, Martin (2003). Italian Unification, 1820–71. Heinemann advanced history. Heinemann. ISBN 0435327542.

- Cunsolo, Ronald S,. "Daniele Manin (1804–1857) Daniele Manin (1804–1857)". Encyclopedia of Revolutions of 1848. Ohio University.

- Cunsolo, Ronald S,. "Venice and the Revolution of 1848–49". Encyclopedia of Revolutions of 1848. Ohio University.

- Dana, James D.; Silliman, B., eds. (July–December 1874). "Miscellaneous Scientific Intelligence". The American Journal of Science and Arts (S. Converse) 8 (43–48).

- Danford, Natalie (October 1994). "Beyond Pizza". Vegetarian Times (Active Interest Media) (109). ISSN 0164-8497.

- Diller, Joseph Silas (1902). "Topographic Development of the Klamath Mountains". U.S. Geological Survey bulletin (U.S. Government Printing Office) (196).

- Dippel, Hosrt, ed. (2009). Constitutions of the World from the late 18th Century to the Middle of the 19th Century. National Constitutions 10. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 9783598357343.

- Ferorelli, Nicola (1925). La vera origine del tricolore italiano. Rassegna storica del Risorgimento 12.

- Frasca, Francesco (2001). "L'esercito del primo tricolore" (PDF). Informazioni della Difesa (Stato Maggiore della Difesa) (6): 49–53.

- Haberman, Clyde (27 September 1989). "Ravenna Journal; After the Unthinkable, the Sky Show Must Go On". The New York Times. Retrieved 23 November 2013.

- Murari, Rocco (1892). La bandiera nazionale italiana : discorso con note e documenti. S. Lapi.

- Oddo, Giacomo (1865). Il brigantaggio; o, L'Italia dopo la dittatura di Garibaldi 3. Giuseppe Scorza di Nicola.

- Partington, Charles F. (1836). The British Cyclopedia of literature, history, geography, law , and politics 2. Orr and Smith.

- Protonotari, Francesco, ed. (1897). "Le origini del tricolore italiano". Nuova Antologia di scienze lettere e arti 151. Direzione della Nuova Antologia.

- Venosta, Felice (1864). Luigi Zamboni: Il primo martire della liberta' Italiana. Francesco Scorza.

- Waley, Daniel Philip; Hearder, Harry, eds. (1963). A short history of Italy, from classical times to the present day. Cambridge University Press.

- Young, Francis; Stevens, W. B. B. (1864). Garibaldi: His Life and Times: Comprising the Revolutionary History of Italy from 1789 to the present time. S.O. Beeton.

- "Italian opposition in flap over flag". BBC News. 28 April 2003. Retrieved 23 November 2013.

- "Tricolore "sbagliato" alla Camera". Corriere della Sera (RCS Quotidiani Spa). 29 April 2003. Retrieved 23 November 2013.

- "Flag and anthem: The Tri-coloured standard". Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Archived from the original on 23 February 2008.

- "Pizza purists out to protect patriotic pie". Lakeland Ledger. Associated Press. 2 March 1989.

- "Rallying to protect 'real' pizza". Philadelphia Enquirer. 5 April 1989.

- Cook's handbook to Venice. Cook Thomas and son, ltd. 1874.

- "Wings". 34–36. Aeronautical Press. 1964.

- Atti e memorie Accademia Nazionale Virgiliana di scienze lettere ed arti. Reale Accademia virgiliana di scienze, lettere ed arti. Biblioteca dell'Accademia virgiliana. 1897.

- "Gli azzurri". Federazione Italiana Pallacanestro. Retrieved 26 November 2013.

- "Le Azzurre". Federazione Italiana Pallacanestro. Retrieved 26 November 2013.

- "Azzurre". Federazione Italiana Pallavolo. Retrieved 26 November 2013.

- "Azzurri". Federazione Italiana Pallavolo. Retrieved 26 November 2013.

- "Legge n. 671 del 31 dicembre 1996: Celebrazione nazionale del bicentenario della prima bandiera nazionale". Gazzetta Ufficiale della Repubblica Italiana. 2 January 1997. Retrieved 26 November 2013.

- "Decreto del presidente della repubblica 9 ottobre 2000: Stendardo del Presidente della Repubblica". Gazzetta Ufficiale della Repubblica Italiana. 9 October 2000. Retrieved 26 November 2013.

- "Disposizioni generali in materia di cerimoniale e di precedenza tra le cariche pubbliche" (PDF). Gazzetta Ufficiale della Repubblica Italiana (L'Istituto Poligrafico e Zecca dello Stato S.p.A) (174). 14 April 2006. Retrieved 24 November 2013.

- "Articolo 12". Senate of the Republic. Retrieved 23 November 2013.

- "Il Tricolore compie duecentodieci anni l'anniversario celebrato in tutta Italia". La Repubblica. 7 January 2007. Retrieved 26 November 2013.

- "Coppa Italia 2012/2013, 2013/2014 e 2014/2015: Regolamento". Lega Nazionale Professionisti. 4 June 2012. Retrieved 26 November 2013.

- "Premiazione scudetto" (in Italian). Lega Nazionale Professionisti. 13 May 2012. Retrieved 2013-11-26.

- "Protocolo di Stato: La Bandiera" (PDF). Prefettura di Pisa. 30 May 2013. Retrieved 24 November 2013.

- "Constitution of the Italian Republic" (PDF). Parliamentary Information, Archives and Publications Office, Senate Service for Official Reports and Communication, Senate of the Republic. Retrieved 23 November 2013.

Further reading

- Gerbaix di Sonnaz, Carlo Alberto (1896). Bandiere, stendardi e vessilli dei conti e duchi di Savoia, marchesi in Italia, principi di Piemonte, re di Cipro, di Sicilia, di Sardegna e d'Italia dal 1200 al 1896. Roux Frassati e Company.

- Aglebert, Augusto (1862). I primi martiri della libertà italiana e l'origine della bandiera tricolore.

External links

- Il Museo del Tricolore (Italian)