Naimark's dilation theorem

In operator theory, Naimark's dilation theorem is a result that characterizes positive operator valued measures. It can be viewed as a consequence of Stinespring's dilation theorem.

Note

In the mathematical literature, one may also find other results that bear Naimark's name.

Some preliminary notions

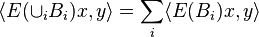

Let X be a compact Hausdorff space, H be a Hilbert space, and L(H) the Banach space of bounded operators on H. A mapping E from the Borel σ-algebra on X to  is called a operator-valued measure if it is weakly countably additive, that is, for any disjoint sequence of Borel sets

is called a operator-valued measure if it is weakly countably additive, that is, for any disjoint sequence of Borel sets  , we have

, we have

for all x and y. Some terminology for describing such measures are:

- E is called regular if the scalar valued measure

is a regular Borel measure, meaning all compact sets have finite total variation and the measure of a set can be approximated by those of open sets.

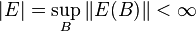

- E is called bounded if

.

.

- E is called positive if E(B) is a positive operator for all B.

- E is called self-adjoint if E(B) is self-adjoint for all B.

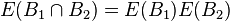

- E is called spectral if it is self-adjoint and

for all

for all  .

.

We will assume throughout that E is regular.

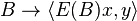

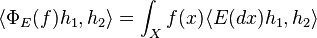

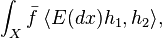

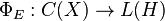

Let C(X) denote the abelian C*-algebra of continuous functions on X. If E is regular and bounded, it induces a map  in the obvious way:

in the obvious way:

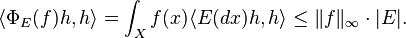

The boundedness of E implies, for all h of unit norm

This shows  is a bounded operator for all f, and

is a bounded operator for all f, and  itself is a bounded linear map as well.

itself is a bounded linear map as well.

The properties of  are directly related to those of E:

are directly related to those of E:

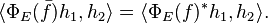

- If E is positive, then

, viewed as a map between C*-algebras, is also positive.

, viewed as a map between C*-algebras, is also positive.

-

is a homomorphism if, by definition, for all continuous f on X and

is a homomorphism if, by definition, for all continuous f on X and  ,

,

Take f and g to be indicator functions of Borel sets and we see that  is a homomorphism if and only if E is spectral.

is a homomorphism if and only if E is spectral.

- Similarly, to say

respects the * operation means

respects the * operation means

The LHS is

and the RHS is

So, taking f a sequence of continuous functions increasing to the indicator function of B, we get  , i.e. E(B) is self adjoint.

, i.e. E(B) is self adjoint.

- Combining the previous two facts gives the conclusion that

is a *-homomorphism if and only if E is spectral and self adjoint. (When E is spectral and self adjoint, E is said to be a projection-valued measure or PVM.)

is a *-homomorphism if and only if E is spectral and self adjoint. (When E is spectral and self adjoint, E is said to be a projection-valued measure or PVM.)

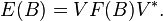

Naimark's theorem

The theorem reads as follows: Let E be a positive L(H)-valued measure on X. There exists a Hilbert space K, a bounded operator  , and a self-adjoint, spectral L(K)-valued measure on X, F, such that

, and a self-adjoint, spectral L(K)-valued measure on X, F, such that

Proof

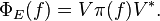

We now sketch the proof. The argument passes E to the induced map  and uses Stinespring's dilation theorem. Since E is positive, so is

and uses Stinespring's dilation theorem. Since E is positive, so is  as a map between C*-algebras, as explained above. Furthermore, because the domain of

as a map between C*-algebras, as explained above. Furthermore, because the domain of  , C(X), is an abelian C*-algebra, we have that

, C(X), is an abelian C*-algebra, we have that  is completely positive. By Stinespring's result, there exists a Hilbert space K, a *-homomorphism

is completely positive. By Stinespring's result, there exists a Hilbert space K, a *-homomorphism  , and operator

, and operator  such that

such that

Since π is a *-homomorphism, its corresponding operator-valued measure F is spectral and self adjoint. It is easily seen that F has the desired properties.

Finite-dimensional case

In the finite-dimensional case, there is a somewhat more explicit formulation.

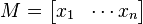

Suppose now  , therefore C(X) is the finite-dimensional algebra

, therefore C(X) is the finite-dimensional algebra  , and H has finite dimension m. A positive operator-valued measure E then assigns each i a positive semidefinite m X m matrix

, and H has finite dimension m. A positive operator-valued measure E then assigns each i a positive semidefinite m X m matrix  . Naimark's theorem now says there

is a projection valued measure on X whose restriction is E.

. Naimark's theorem now says there

is a projection valued measure on X whose restriction is E.

Of particular interest is the special case when  where I is the identity operator. (See the article on POVM for relevant applications.) This would mean the induced map

where I is the identity operator. (See the article on POVM for relevant applications.) This would mean the induced map  is unital. It can be assumed with no loss of generality that each

is unital. It can be assumed with no loss of generality that each  is a rank-one projection onto some

is a rank-one projection onto some  . Under such assumptions, the case

. Under such assumptions, the case  is excluded and we must have either:

is excluded and we must have either:

1)  and E is already a projection valued measure. (Because

and E is already a projection valued measure. (Because  if and only if

if and only if  is an orthonormal basis.)

,or

is an orthonormal basis.)

,or

2)  and

and  does not consist of mutually orthogonal projections.

does not consist of mutually orthogonal projections.

For the second possibility, the problem of finding a suitable PVM now becomes the following: By assumption, the non-square matrix

is an isometry, i.e.  . If we can find a

. If we can find a  matrix N where

matrix N where

is a n X n unitary matrix, the PVM whose elements are projections onto the column vectors of U will then have the desired properties. In principle, such a N can always be found.

References

- V. Paulsen, Completely Bounded Maps and Operator Algebras, Cambridge University Press, 2003.