Mycocepurus smithii

| Mycocepurus smithii | |

|---|---|

| |

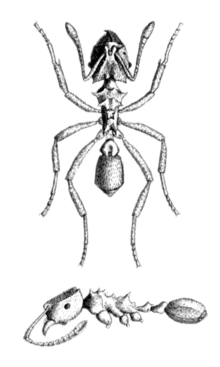

| Specimen of Mycocepurus smithii | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Hymenoptera |

| Suborder: | Apocrita |

| Superfamily: | Vespoidea |

| Family: | Formicidae |

| Subfamily: | Myrmicinae |

| Tribe: | Attini |

| Genus: | Mycocepurus |

| Species: | M. smithii |

| Binomial name | |

| Mycocepurus smithii (Forel, 1893) | |

| |

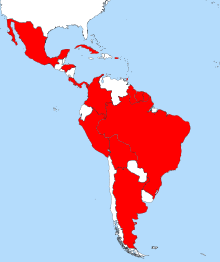

| Distribution of Mycocepurus smithii | |

Mycocepurus smithii is an attine fungus-growing ant from Latin America. While a widely reported study from 2009 claimed that the species consists exclusively of females which reproduce asexually a latter work in 2011 found evidence of sexual reproduction is some populations. In many colonies queen reproduces by parthenogenesis and all other ants in a colony are female clones of the queen.[1] The ants cultivate a garden of fungus inside their colony grown with pieces of dead vegetables and other insects. It is this capacity for farming which initially prompted research into the species as a basal genus member would provide insight into the natural history of the fungal-cultivating ant tribe, Attini.[2]

Description

Ants of the genus Mycocepurus are distinctly recognizable for the crown-like cluster of horns on their promesonotum, the fused mesonotum and pronotum on the front of their alitrunk or midsection. M. smithii has sharp, protruding propodeal (posterior of the alitrunk) spines unlike M. obsoletus whose propodeal spines are blunt. Workers also do not have developed promesonotal spines in the center of their crown.[3]

Fungal cultivation

Foundress queens shed their wings prior to colony excavation either near the site or just inside. They then excavate a tunnel to a depth of roughly 10 cm (4 in) and create a primary chamber. The dealate queen then carries the wings into the primary chamber and inserts them into the chamber ceiling where the surface of the wings is used as a platform for growing an incipient fungal garden. The female fore wings of all three Attini basal genera (Mycocepurus, Apterostigma, and Myrmicocrypta) have a crescent-shaped spot lacking any veins or pigmentation, though the spot's functionality is unknown.[2]

Nest architecture

M. smithii nests in Puerto Rico, Costa Rica, and Trinidad have a single entrance, though the close proximity to other nests in high colony-density areas may give the illusion of multiple entrances.[2] M. Smithii nests consist of a mound excavated around an entrance roughly 1.2 mm in diameter.[4] This leads to a vertical tunnel opening into the garden chamber at a depth of about 12.5 mm.[4] M. smithii ants maintain narrow tunnels (diameter of 1.3 mm) which do not allow two ants to pass each other in the tunnel (head size is around 0.7 mm for workers and 0.9 mm for queens).[2] The tunnels also have a number of slightly larger sections (about 3.6 mm diameter) which would allow passing while also facilitating information exchange. Narrow tunnels are presumably easier (energetically cheaper) to construct and may also aide in leveling the humidity or temperature of the colony or preventing predatory intrusions.[2]

Reproduction

No male individuals of M. smithii have ever been identified, and when researchers examined 6 widely dispersed sites the discovered that all of the workers of each colony were genetically identical with the queen. That fact, together with evidence that the mussel organ, a female docking apparatus within the vagina used to hook the mate's genitalia, has degenerated in dissected queens led to the conclusion that M. smithii was the first ant species to reproduce entirely asexually through parthenogenesis.[5][6]

However, a follow-up study surveying additional locations identified a set of colonies along the Amazon and Rio Negro whose genetic diversity is clear evidence of ongoing sexual reproduction. Furthermore, the researchers identified stored sperm in the reproductive tracts of queens from those colonies. Thus they concluded that "M. smithii actually consists of a mosaic of asexual and sexual populations."[7]

References

- ↑ Jamieson, Alastair (2009-04-16). "Females get along fine without males - in the world of tropical ants". London: The Telegraph. Retrieved 2009-04-17.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Fernandez-Marin, H.; Zimmerman, J. K.; Wcislo, W. T.; Rehner, S. A. (2005). "Colony foundation, nest architecture and demography of a basal fungus-growing ant, Mycocepurus smithii (Hymenoptera, Formicidae)". Journal of Natural History 39 (20): 1735–1743. doi:10.1080/00222930400027462. Retrieved 2009-04-19.

- ↑ Mackay, William P.; Maes, Jean-Michel; Fernández, Patricia Rojas; Luna, Gladys; (2004-08-24). "The ants of North and Central America: the genus Mycocepurus (Hymenoptera: Formicidae)". The Journal of Insect Science 4: 27. doi:10.1093/jis/4.1.27. ISSN 1536-2442. PMC 1081568. PMID 15861242. Retrieved 2009-04-20.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Fernández-Marín, H; Zimmerman, J.K.; Wcislo, W.T. (2004). "Ecological traits and evolutionary sequence of nest establishment in fungus-growing ants (Hymenoptera, Formicidae, Attini)". Biological Journal of the Linnean Society 81: 39–48. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8312.2004.00268.x. Retrieved 2009-04-20.

- ↑ Himler AG, Caldera EJ, Baer BC, Fernández-Marín H, Mueller UG (2009). "No sex in fungus-farming ants or their crops". Proceedings of the Royal Society B 276 (1667): 2611–6. doi:10.1098/rspb.2009.0313. PMC 2686657. PMID 19369264. Lay summary – BBC News (2009-04-15).

- ↑ Baer, Boris; Boomsma, Jacobus J. (2006). "Mating Biology of the Leaf-Cutting Ants Atta colombica and A. cephalotes". Journal of Morphology 267 (10): 1165–1171. doi:10.1002/jmor.10467. PMID 16817214. Retrieved 2009-04-19.

- ↑ Rabeling, Christian; Gonzales, Omar; Schultz, Ted R.; Bacci, Maurício; Garcia, Marcos V. B.; Verhaagh, Manfred; Ishak, Heather D.; Mueller, Ulrich G. (June 14, 2011). "Cryptic sexual populations account for genetic diversity and ecological success in a widely distributed, asexual fungus-growing ant". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 108 (30): 12366–12371. doi:10.1073/pnas.1105467108. Retrieved September 21, 2014.

Further reading

- Anna Grace Himler, Ph.D. Dissertation: Evolutionary Ecology and Natural History of Fungus-Growing Ants: Host-Switching, Divergence, and Asexuality. Chapter 3. No sex in fungus-farming ants or their crops, 2007.

External links

Media related to Mycocepurus smithii at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Mycocepurus smithii at Wikimedia Commons- Photograph of Mycocepurus smithii at myrmecos.net