Mycenaean Greece

| |

| Period | Bronze Age |

|---|---|

| Dates | c. 1600 BC – 1100 BC |

| Preceded by | Minoan civilization |

| Followed by | Greek Dark Ages |

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Greece |

|

|

|

|

History by topic |

| Greece portal |

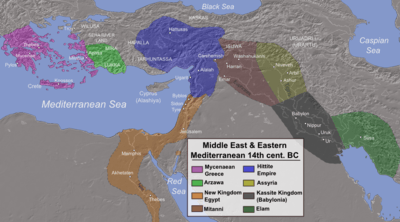

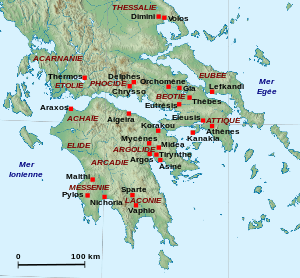

Mycenaean Greece refers to the last phase of the Bronze Age in Ancient Greece (c. 1600–1100 BC). It represents the first advanced civilization in mainland Greece, with its palatial states, urban organization, works of art and writing system.[1] Among the centers of power emerged the most notable were that of Pylos, Tiryns, Midea in Peloponnese, Orchomenos, Thebes, Athens in Central Greece and Iolcos in Thessaly. The most prominent site was Mycenae, in Argolid, to which the culture of this era owes its name. Mycenaean and Mycenaean influenced settlements also appeared in Epirus,[2][3] Macedonia,[4][5] on islands in the Aegean Sea, on the coast of Asia Minor, the Levant,[6] Cyprus[7] and Italy.[8]

Mycenaean Greece perished with the collapse of Bronze-Age culture in the eastern Mediterranean. Various theories have been proposed for the end of this civilization, among them the Dorian invasion or activities connected to the “Sea People”. Additional theories such as natural disasters and climatic changes have been also suggested. The Mycenaean period became the historical setting of much ancient Greek literature and mythology, including the Trojan Epic Cycle.[9]

Chronology

The Bronze Age in mainland Greece is generally termed as the "Helladic period" by modern archaeologists, after Hellas, the Greek name for Greece. This period is divided into three subperiods: The Early Helladic (EH) period (c. 2900–2000 BC) was a time of prosperity with the use of metals and a growth in technology, economy and social organization. The Middle Helladic (MH) period (ca. 2000–1650 BC) faced a slower pace of development, as well as the evolution of megaron-type cist graves.[1] Finally, the Late Helladic (LH) period (c. 1650–1050 BC) roughly coincides with Mycenaean Greece.[1]

The Late Helladic period is further divided into LHI, LHII, both of which coincide with the early period of Mycenaean Greece (c. 1650–1425 BC), and LHIII (c. 1425–1050 BC), the period of expansion, decline and collapse of the Mycenaean civilization.[1] The transition period from the Bronze Age to the Iron Age in Greece is known as Sub-Mycenaean (c. 1050–1000 BC).[1]

Identity

The decipherment of the Mycenaean Linear B script, a writing system adapted for the use of the Greek language of the Late Bronze Age,[10] demonstrated the continuity of Greek speech from the 2nd millennium BC into the 8th century BC when a new script emerged. Moreover, it pointed out that the bearers of Mycenaean culture were ethnically connected with the populations that resided in the Greek peninsula after the end of this cultural period.[11] Various collective terms for the inhabitants of Mycenaean Greece were used by Homer in his 8th century BC epic, the Iliad, in reference to the Trojan War. The latter was supposed to happen in the late 13th–early 12th century BC, where a coalition of small Greek states under the king of Mycenae, besieged the walled city of Troy. Homer used the ethnonyms: Achaeans, Danaans and Argives, to refer to the besiegers.[12] These names appear to have passed down from the time they were in use to the time when Homer applied them as collective terms in his Iliad.[13] There is an isolated reference to a-ka-wi-ja-de in the Linear B records in Knossos, Crete dated to c. 1400 BC, which most probably refers to a Mycenaean (Achaean) state on the Greek mainland.[14]

Egyptian records mention a T(D)-n-j or Danaya (Tanaju) land for the first time in ca. 1437 BC, during the reign Pharaoh Thutmoses III. This land is geographically defined in an inscription from the reign of Amenhotep III (c. 1388–1351 BC), where a number of Danaya cities are mentioned, which cover the largest part of southern mainland Greece.[15] Among them, cities such as Mycenae, Nauplion and Thebes, have been identified with certainty. Danaya has been equated with the ethnonym Danaoi (Greek: Δαναοί), the name of the mythical dynasty that ruled in the region of Argos, also used as an ethnonym for the Greek people by Homer.[15][16]

In the official records of another Bronze Age empire, that of the Hittites in Anatolia various references, from c. 1400 BC to 1220 BC, mention a country named Ahhiyawa.[17][18] Recent scholarship, based on textual evidence, new interpretations of the Hittite inscriptions, as well as on recent surveys about the archaeological evidence about Mycenaean-Anatolian contacts during this period, concludes that the term Ahhiyawa must have been used in reference to the Mycenaean world (land of the Achaeans), or at least to a part of it.[19][20] This term may have also had broader connotations in some texts, possibly referring to all regions settled by Mycenaeans or regions under direct Mycenaean political control.[17] Another similar ethnonym Ekwesh in 12th century BC Egyptian inscriptions, has been commonly identified with the Ahhiyawans. These Ekwesh were mentioned as a group of the Sea People.[21]

History

Shaft Grave era (c. 1600–1450 BC)

Mycenaean civilization originated and evolved from the society and culture of the Early and Middle Helladic period in mainland Greece under influences from Minoan Crete.[22] Towards the end of the Middle Bronze Age (c. 1600 BC) a significant increase in the population and the number of settlements occurred.[23] A number of centres of power emerged in southern mainland Greece dominated by a warrior elite society,[1][24] while the typical dwellings of that era were an early type of megaron buildings. Some more complex structures are classified as forerunners of the later palaces. In a number of sites, defensive walls were also erected.[25]

Meanwhile, new types of burials and more imposing ones have been unearthed, which display a great variety of luxurious objects.[23][26] Among the various burials types, the shaft grave became the most common form of elite burial, a feature that gave the name to the early period of Mycenaean Greece.[23] Among the Mycenaean elite, deceased males were usually laid in gold masks and funerary armor, while females in gold crowns and clothes gleaming with gold ornaments.[27] The royal shaft graves next to the acropolis of Mycenae, in particular the Grave Circles A and B signified the elevation of a native Greek-speaking royal dynasty whose economic power depended on long-distance sea trade.[28]

During this period, the Mycenaean centers witnessed increased contacts with the outside world and especially with the Cyclades and the Minoan centers in the island of Crete.[1][23] Mycenaean presence appears to be also depicted in a fresco at Akrotiri, on Thera island, which possibly displays many warriors in Boar's tusk helmets, a feature typical of Mycenaean warfare.[29] In the early 15th century, commerce intensified with Mycenaean pottery reaching the western coast of Asia Minor, including Miletus and Troy, Cyprus, Lebanon, Palestine and Egypt.[30]

At the end of the Shaft Grave era, a new and more imposing type of elite burial emerged, the Tholos: large circular burial chambers with high vaulted roofs and a straight entry passage lined with stone.[31]

Mycenaean Koine era (c. 1450 BC–1250 BC)

The eruption of Thera, which according to archaeological data occurred in c. 1500 BC, resulted in the decline of the Minoan civilization of Crete.[32] This turn of events gave the opportunity to the Mycenaeans to spread their influence throughout the Aegean. Around c. 1450 BC, they were in control of Crete itself, including Knossos, and colonized several other Aegean islands, reaching as far as Rhodes.[33][34] Thus the Mycenaeans became the dominant power of the region, marking the beginning of the Mycenaean 'Koine' era (from Greek: Κοινή, common), a highly uniform culture that spread in mainland Greece and the Aegean.[35]

From the early 14th century BC, Mycenaean trade began to take advantage of the new trading opportunities in the Mediterranean after the Minoan collapse.[34] The trade routes were expanded further reaching Cyprus, Amman in the Near East, Apulia in Italy and Spain.[34] At that time (c. 1400 BC), the palace of Knossos yielded the earliest records of the Greek Linear B script, based on the previous Linear A of the Minoans. The use of the new script spread in mainland Greece and offers valuable insight of the administrative network of the palatial centres. However, the unearthed records are of limited value for the reconstruction of the political landscape in Bronze Age Greece.[36]

Excavations at Miletus, southwest Asia Minor, suggest that Mycenaeans settled there already from c. 1450 BC, replacing the previous Minoan installations.[37] This site became a sizable and prosperous Mycenaean centre for most of the Late Bronze Age until the 12th century BC.[38] Apart from the archaeological evidence, this is also attested in Hittite records, which indicate that Miletos (Milawata in Hittite) was the most important base for Mycenaean activity in Asia Minor.[39] Mycenaean presence also reached the adjacent sites of Iasus and Ephesus.[40]

Meanwhile, imposing palaces were built in the main Mycenaean centres of the mainland. The earliest palace structures were megaron-type buildings, such as the Menelaion in Sparta, Lakonia.[41] Palaces proper are datable from c. 1400 BC, when Cyclopean fortifications were erected at Mycenae and nearby Tiryns.[1] Additional palaces were built in Midea and Pylos in Peloponnese, Athens, Eleusis, Thebes and Orchomenos in Central Greece and Iolcos, in Thessaly, the latter being the northernmost Mycenaean center. Knossos in Crete became also a Mycenaean center, where the former Minoan complex intervened a number of adjustments, including the addition of a throne room.[42] These centres were based on a rigid network of bureaucracy while administrative competences, were classified in various sections and offices, according to specialization of work and trades. At the head of this society was the king, known as wanax (Linear B: wa-na-ka) in Mycenaean Greek terms. All powers were centred on him, who was the main landlord, the spiritual and military leader. At the same time he was an entrepreneur and trader and was aided by a network of high officials. The activities of the wanax covered virtually all aspects of palatial life, as the Linear B records indicate.[43]

Involvement in Asia Minor

Contemporary Hittite texts indicate the presence of Ahhiyawa which strengthens its position in western Anatolia from c. 1400 to c. 1220 BC.[44] Ahhiyawa is generally accepted as a Hittite translation of Mycenaean Greece (Achaeans in Homeric Greek), but a precise geographical definition of the term cannot be drawn from the texts.[45] During this period, the kings of Ahhiyawa were clearly able to deal with the Hittite kings both in a military and diplomatic way.[46] Moreover, Ahhiyawan activity was to interfere in Anatolian affairs, with the support of anti-Hittite uprisings or through local vassal rulers, which the Ahhiyawan king used as agents for the extension of his influence.[47] The Ahhiyawan presence in western Anatolia inevitably caused tensions and in some cases conflicts with the Hittites, whose sphere of influence extended in the same region.[48]

In c. 1400 BC, Hittite records mention the military activities of an Ahhiyawan warlord, Attarsiya, a possible Hittite way of writing the Greek name Atreus, who attacked Hittite vassals in western Anatolia.[49] Later, in c. 1315 BC, Hittite interests in the region were again threatened by an anti-Hittite rebellion headed by Arzawa, a Hittite vassal state, with the support of the king of Ahhiyawa.[50] Around the same time, Ahhiyawa is reported to have seized various islands, presumably in the Aegean, an impression also supported by archaeological evidence.[51] During the reign of the Hittite king Hattusili III (c. 1267–1237 BC), the king of Ahhiyawa is recognized as a "Great King" and of equal status with the other contemporary great Bronze Age rulers: the kings of Egypt, Babylonia and Assyria.[52] At that time, another anti-Hittite movement, led by Piyama-Radu, broke out and was supported by the king of Ahhiyawa.[53] Piyama-Radu had been ravaging the land of Wilusa and latter led the armed takeover of the island of Lesbos, which was subsequently handed over to Ahhiyawa.[54]

The Hittite-Ahhiyawan confrontation in Wilusa, the Hittite name for Troy, may provide the historical foundation for the Trojan War tradition.[55] As a result of this instability, the Hittite king initiated correspondence in order to convince his Ahhiyawan counterpart to restore peace in the region. The Hittite record mentions a certain Tawagalawa, a possible Hittite translation for Greek Eteocles, as brother of the king of Ahhiyawa.[54][56]

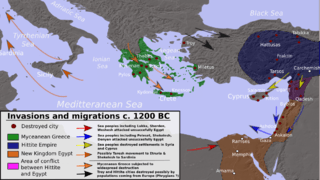

Collapse (c. 1250–1100 BC)

Initial decline and revival

In. c. 1250 BC, the first wave of destruction has been witnessed in various centers of mainland Greece for reasons that cannot be identified by archaeologists. In Boeotia, Thebes was burnt to the ground, around that year or slightly later. Nearby Orchomenos shared the same fate, while the Boeotian fortifications of Gla were deserted.[57] In the Peloponnese, a number of buildings surrounding the citadel of Mycenae were attacked and burnt.[58]

These incidents appear to have prompted the massive strengthening and expansion of the fortifications in various sites. In some cases, arrangements were also made for the creation of subterranean passages which lead to underground cisterns. Tiryns, Midea and Athens expanded their defences with new cyclopean style walls.[59] The extension program in Mycenae almost doubled the fortified area of the citadel. To this phase of extension belongs the impressive Lion Gate, the main entrance into the Mycenaean acropolis.[59]

It appears that after this first wave of destruction a short lived revival of Mycenaean culture followed.[60] Mycenaean Greece continues to be mentioned in international affairs, particularly in Hittite records. In c. 1220 BC, the king of Ahhiyawa is again reported of being involved in an anti-Hittite uprising in western Anatolia.[61] Another contemporary Hittite text reveals that Ahhiyawan ships need to be prohibited from reaching Assyrian-controlled harbors, as part of a trade embargo imposed on Assyria.[62] In general, in the second half of 13th century BC, trade was in decline in the Eastern Mediterranean, most probably due to the unstable political environment there.[63]

Final collapse

None of the defence measures appear to have prevented the final destruction and collapse of the Mycenaean states. A second destruction struck Mycenae in ca. 1190 BC or shortly thereafter. This event marked the end of Mycenae as a major power. The site was then reoccupied, but on a smaller scale.[64] The palace of Pylos, in southwestern Peloponesse, faced destruction in c. 1180 BC.[65][66] The Linear B archives found there, preserved by the heat of the fire that destroyed the palace, mention hastily defence preparations due to an imminent attack without giving any detail about the attacking force.[60]

As a result of this turmoil, specific regions in mainland Greece witnessed dramatic population decreases, especially Boetia, Argolis and Messenia.[60] Mycenaean refugees migrated to Cyprus and the Levantine coast.[66] Nevertheless, other regions on the edge of the Mycenaean world prospered, such as the Ionian islands, northwestern Peloponnese, parts of Attica and a number of Aegean islands.[60] The acropolis of Athens paradoxically appears to have avoided destruction.[60]

Hypotheses for the Mycenaean collapse

The reasons that lead to the collapse of the Mycenaean culture have been hotly debated among scholars. At present, there is no satisfactory explanation for the collapse of the Mycenaean palace systems. The two most common theories are population movement and internal conflict. The first attributes the destruction of Mycenaean sites to invaders.[67]

The hypothesis of a Dorian invasion, known as such in Ancient Greek tradition, that led to the end of Mycenaean Greece, is supported by sporadic archaeological evidence such as new types of burials, in particular cist graves, and the use of a new dialect of Greek, the Doric one. It appears that the Dorians moved southward gradually over a number of years and devastated the territory, until they managed to establish themselves in the Mycenaean centres.[68] A new type of ceramic also appeared, called "Barbarian Ware" because it was attributed to invaders from the north.[60] On the other hand, the collapse of Mycenaean Greece coincides with the activity of the Sea Peoples in the Eastern Mediterranean. They caused widespread destruction in Anatolia and the Levant and were finally defeated by Pharaoh Ramesses III in c. 1175 BC. One of the ethnic groups that consisted these people were the Eqwesh, a name that appears to be linked with the Ahhiyawa of the Hittite inscriptions.[69]

Alternative scenarios propose that the fall of the Mycenaean Greece was a result of internal disturbances which lead to internecine warfare among the Mycenaean states or civil unrest in a number of states, as a result of the strict hierarchical social system and the ideology of the wanax.[70] In general, due to the obscure archaeological picture in 12th-11th century BC Greece, there is a continuing controversy among scholars over whether the impoverished societies that succeeded the Mycenaean palatial states were newcomers or populations that already resided in Mycenaean Greece. Recent archaeological findings tend to favor the latter scenario.[60] Additional theories, concerning natural factors, such as climate change, droughts or earthquakes have been also proposed.[70] The period following the end of Mycenaean Greece, c. 1100-800 BC, is generally termed the "Greek Dark Ages".[71]

Political organization

Patalial states

In ancient Greek tradition, there were several states, like the ones recorded in the Iliad's Catalogue of Ships, as well as discovered by archaeologists. Each Mycenaean kingdom was in principle governed from the palace, which exercised control over most, if not all, industries within its realm. The palatial territory was divided into several provinces, each headed by its own administrative center,[72] while each province was further divided in smaller districts, the da-mo.[72] A number of palaces and fortifications appear to be part of a wider kingdom. Thus, in Boeotia, Gla, was part of the state of Orchomenos.[73] Moreover, Mycenae ruled a territory at least two and arguably even three times the size of other palatial states in Bronze Age Greece. Moreover, its territory would have also included adjacent centers, such as Tiryns and Nauplion, which could plausibly be seen as important yet dependent settlements, ruled by branches of Mycenae’s royal dynasty.[74]

The unearthed Linear B texts are in general of limited value for the reconstruction of the political landscape in Mycenaean Greece and they do not support the existence of a larger Mycenaean state.[75][76] On the other hand, contemporary Hittite and Egyptian records suggest the presence of a unified state under a single leader.[77] Alternatively, based on archaeological data, some sort of confederation among a number of palatial states appears to be possible.[76] If some kind of united political entity existed, the dominant center was probably located in Thebes or in Mycenae, with the last one being the most possible.[78]

Society and administration

The Neolithic agrarian village (6000 BC) constituted the foundation of Bronze Age political culture in Greece.[79] The vast majority of the preserved Linear B records deals with administrative issues and give the impression that palatial administration throughout Greece was highly uniform with the use of the same language, terminology, system of taxation and distribution.[80][72] Considering this sense of uniformity, the evidence coming from the most fully preserved archive, that of the palace of Pylos, is in general taken as representative of all the palatial centers of the Mycenaean world.[80]

The state was ruled by a king, the wanax (ϝάναξ), whose role was religious and perhaps also military and judicial.[81] The wanax covered virtually all aspects of palatial life, from religious feasting and offerings to the distribution of goods and craftsmen or troops.[82] Under him was the lāwāgetas ("the leader of the people"), whose role appears mainly religious.[82] His activities seem to roughly overlap with the wanax and is usually seen as the second-in-command.[82] Both anax and lāwāgetas stood at the head of a military aristocracy known as the eqeta ("companions" or "followers"),[83][81] The land possessed by the wanax is usually the témenos (te-me-no). There is also at least one instance of a person, Enkhelyawon, at Pylos, who appears titleless in the written record but whom modern scholars regard as being probably a king.[84]

A number of local officials positioned by the wanax, appear to be in charge of the districts, such as ko-re-te (koreter, '"governor"), po-ro-ko-re-te (prokoreter, "deputy") and the da-mo-ko-ro (damokoros, "one who takes care of a damos"), the latter being appointed probably in charge of the commune. A council of elders was chaired, the ke-ro-si-ja (cf. γερουσία, gerousía). The basileus, who in latter Greek society was the name of the king, refers to communal officials.[81]

In general, Mycenaean society appears to have been divided into two groups of free men: the king's entourage, who conducted administrative duties at the palace and the people, da-mo,[85] These last were watched over by royal agents and were obliged to perform duties for and pay taxes to the palace.[81] Among those who evolved in the palace setting could be found well-to-do high officials who probably lived in the vast residences found in proximity to Mycenaean palaces, but also others, tied by their work to the palace and not necessarily better off than the members of the da-mo, such as craftsmen, farmers, and perhaps merchants. On a lower rung of the social ladder were found the slaves, do-e-ro, (cf. δοῦλος, doúlos).[86] These are recorded in the texts as working either for the palace or for specific deities.[81]

Economy

The economic organization of the Mycenaean kingdoms known from the texts seems to have been bipartite: a first group worked in the orbit of the palace, while another was self-employed. This reflects the societal structure seen above. However, there was nothing to prevent a person working for the palace from running his own business. The economy was supervised by scribes, who made note of incoming and outgoing products, assigned work, and were in charge of the distribution of rations. The du-ma-te seems to have been a sort of supervising quartermaster.

Agriculture

The territory of the Mycenaean kingdoms of Pylos and Knossos was divided into two parts: the ki-ti-me-na, the palace land, and the ke-ke-me-na, the communal land, cultivated by those the texts call ka-ma-na-e-we, undoubtedly the da-mo. The palace lands are those attested in the texts. One part makes up the te-me-no of the wa-ka-na and of the ra-wa-ge-ta, as seen above. The other part was granted as a perquisite to members of the palace administration. These lands might be worked by slaves or by free men to whom the land had been leased.

Agricultural production in these kingdoms reflected the traditional "Mediterranean trilogy": grain, olives, and grapes. The grains cultivated were wheat and barley. Olive orchards were planted for the production of olive oil. This was not only a foodstuff, it was much used as a body oil and in perfume. Grapes were also cultivated, and several varieties of wine were produced. Besides these, flax was grown for linen clothing and sesame for its oil, and trees were planted, such as the fig.

Livestock consisted primarily of sheep and goats. Cows and pigs were less common. Horses were kept chiefly for the pulling of chariots in battle.

Industry

The organization of artisanal labor is especially well known in the case of the palace. The archives of Pylos show a specialized workforce, each worker belonging to a precise category and assigned to a specific place in the stages of production, notably in textiles.

The textile industry was one of the principal sectors of the Mycenaean economy. The tablets of Knossos reveal the entire chain of production, from the flocks of sheep to the stocking of the palace storerooms with the finished product, through the shearing and the sorting of the wool in the workshops, as well as working conditions in those workshops. The palace of Pylos employed around 550 textile workers. At Knossos, there were some 900. Fifteen different textile specialties have been identified. Next to wool, flax was the fiber most used. The largest Mycenaean workshop, at least 3,000 square meters in area, dedicated to the processing of flax was recently discovered in Euonymeia.

The metallurgical industry is well attested at Pylos, where 400 workers were employed. It is known from the sources that metal was distributed to them, that they might carry out the required work: on average, 3.5 kilograms (7.7 lb) of bronze per smith. On the other hand, it is not known how they were paid — they are mysteriously absent in the ration distribution lists. At Knossos, several tablets testify to the making of swords, but with no mention of the true industry of metallurgy.

The industry of perfumery is attested as well. Tablets describe the making of perfumed oil. It is known, too, from the archaeology that the workers attached to the palace included other kinds of artisans: goldsmiths, ivory-carvers, stonecarvers, and potters, for example. Olive oil was also made there. Certain areas of endeavor were turned toward export.

Commerce

Commerce remains curiously absent from the written sources. Thus, once the perfumed oil of Pylos has been stored in its little jars, the inscriptions do not reveal what became of it. Large stirrup jars that once contained oil have been found at Thebes in Boeotia. They carry inscriptions in Linear B indicating their place of origin, western Crete. However, Cretan tablets say nothing about the exportation of oil. There is little information about the distribution route of textiles. It is known that the Minoans exported fine fabrics to Egypt; the Mycenaeans no doubt did the same. Indeed, it is probable that they borrowed knowledge of navigational matters from the Minoans, as is evidenced by the fact that their maritime commerce did not take off until after the founding of the Minoan civilization. Despite the lack of sources, it is probable that certain products, notably fabrics and oil, even metal objects, were meant to be sold outside the kingdom, for they were made in quantities too great to be consumed solely at home.

Archaeology can, however, shed some light on the matter of the exportation of Mycenaean products outside of Greece. A number of vases have been found in the Aegean, in Anatolia, the Levant, Egypt and farther west in Sicily, even in Central Europe and as far away as Great Britain.[87] Moreover, Mycenaean swords are known from as far away as Georgia in the Caucasus,[88] an amber object inscribed with Linear B symbols has been found in Bavaria, Germany[89] and Mycenaean bronze double axes and other objects dating from the 13th century BC have been found in Ireland and in Wessex and Cornwall in England.[90][91]

In a general way, the circulation of Mycenaean goods is traceable thanks to nodules, ancestors of the modern label. They consisted of small balls of clay, molded with the fingers around a lanyard (probably of leather) with which they were attached to the object. The nodule displayed the imprint of a seal and an ideogram representing the object. Other information was sometimes added: quality, origin, destination, etc.

By the close of the Bronze Age (up to Late Helladic IIIC) contacts between the Aegean and its neighbours were well established. Mycenaean connections extended as far as Sardinia.[92] Southern Italy and Sicily,[93] Asia Minor[94] While Mycenaean pottery has been found as far as Cyprus,[95] the Levant,[96] Egypt (especially Tell el Amarna[97]) and even southern Spain.[98] The circulation of goods and produce between centres are attested in Linear B records, though evidence of direct exchange is not.

Fifty-six nodules found at Thebes in 1982 carry an ideogram representing an ox. Thanks to them, the itinerary of these bovines can be reconstructed. From all over Boeotia, even from Euboea, they were taken to Thebes to be sacrificed. The nodules served to prove that they were not stolen animals and to prove their origin. Once the animals arrived at their destination, the nodules were removed and gathered to create a book-keeping tablet. The nodules were used for all sorts of objects and explain how Mycenaean book-keeping could have been so rigorous. The scribe did not have to count the objects themselves, he could base his tables upon the nodules.

Religion

The religious element is difficult to identify in Mycenaean civilization, especially as regards archaeological sites, where it remains problematic to pick out a place of worship with certainty. John Chadwick points out that at least six centuries lie between the earliest presence of proto-Greek speakers in Hellas and the earliest Linear B inscriptions, during which concepts and practices will have fused with indigenous beliefs, and—if cultural influences in material culture reflect influences in religious beliefs—with Minoan religion.[99] As for these texts, the few lists of offerings that give names of gods as recipients of goods reveal nothing about religious practices, and there is no surviving literature. John Chadwick rejected a confusion of Minoan and Mycenaean religion derived from archaeological correlations[100] and cautioned against "the attempt to uncover the prehistory of classical Greek religion by conjecturing its origins and guessing the meaning of its myths"[101] above all through treacherous etymologies.[102] Moses I. Finley detected very few authentic Mycenaean reflections in the eighth-century Homeric world, in spite of its "Mycenaean" setting.[103] However, Nilsson asserts, based not on uncertain etymologies but on religious elements and on the representations and general function of the gods, that a lot of Minoan gods and religious conceptions were fused in the Mycenaean religion. From the existing evidence, it seems that the Mycenaean religion was the mother of the Greek religion.[104] The Mycenaean pantheon already included many divinities that can be found in Classical Greece.[105]

Poseidon (Po-se-da-o) seems to have occupied a place of privilege. He was a chthonic deity, connected with the earthquakes (E-ne-si-da-o-ne: earth shaker), but it seems that he also represented the river spirit of the underworld as it often happens in Northern European folklore.[106] Also to be found are a collection of "Ladies". On a number of tablets from Pylos, we find Po-ti-ni-ja (Potnia, "lady" or "mistress") without any accompanying word. It seems that she had an important shrine at the site Pakijanes near Pylos.[107] In an inscription at Knossos in Crete, we find the "mistress of the Labyrinth" (da-pu-ri-to-jo po-ti-ni-ja), who calls to mind the myth of the Minoan labyrinth.[108] The title was applied to many goddesses. In a Linear B tablet found at Pylos, the "two queens and the king" (wa-na-ssoi, wa-na-ka-te) are mentioned, and John Chadwick relates these with the precursor goddesses of Demeter, Persephone and Poseidon.[109][110]

Demeter and her daughter Persephone, the goddesses of the Eleusinian mysteries, were usually referred to as "the two goddesses" or "the mistresses" in historical times.[111] Inscriptions in Linear B found at Pylos, mention the goddesses Pe-re-swa, who may be related with Persephone, and Si-to po-ti-ni-ja,[112] who is an agricultural goddess.[107] A cult title of Demeter is "Sito" (σίτος: wheat).[113] The mysteries were established during the Mycenean period (1500 BC) at the city of Eleusis[114] and it seems that they were based on a pre-Greek vegetation cult with Minoan elements.[115] The cult was originally private and there is no information about it, but certain elements suggest that it could have similarities with the cult of Despoina ("the mistress") - the precursor goddess of Persephone - in isolated Arcadia that survived up to classical times. In the primitive Arcadian myth, Poseidon, the river spirit of the underworld, appears as a horse (Poseidon Hippios). He pursues Demeter who becomes a mare and from the union she bears the fabulous horse Arion and a daughter, "Despoina", who obviously originally had the shape or the head of a mare. Pausanias mentions animal-headed statues of Demeter and of other gods in Arcadia.[116] At Lycosura on a marble relief, appear figures of women with the heads of different animals, obviously in a ritual dance.[117] This could explain a Mycenaean fresco from 1400 BC that represents a procession with animal masks[118] and the procession of "daemons" in front of a goddess on a goldring from Tiryns.[119] The Greek myth of the Minotaur probably originated from a similar "daemon".[120] In the cult of Despoina at Lycosura, the two goddesses are closely connected with the springs and the animals, and especially with Poseidon and Artemis, the "mistress of the animals" who was the first nymph. The existence of the nymphs was bound to the trees or the waters which they haunted.

Artemis appears as a daughter of Demeter in the Arcadian cults and she became the most popular goddess in Greece.[121] The earliest attested forms of the name Artemis are the Mycenaean Greek a-te-mi-to and a-ti-mi-te, written in Linear B at Pylos.[122] Her precursor goddess (probably the Minoan Britomartis) is represented between two lions on a Minoan seal and also on some goldrings from Mycenae.[123] The representations are quite similar with those of "Artemis Orthia" at Sparta. In her temple at Sparta, wooden masks representing human faces have been found that were used by dancers in the vegetation-cult.[124] Artemis was also connected with the Minoan "cult of the tree," an ecstatic and orgiastic cult, which is represented on Minoan seals and Mycenaean gold rings.[125]

Paean (Pa-ja-wo) is probably the precursor of the Greek physician of the gods in Homer's Iliad. He was the personification of the magic-song which was supposed to "heal" the patient. Later it became also a song of victory (παιάν). The magicians was also called "seer- doctors" (ιατρομάντεις), a function which was also applied later to Apollo.[126]

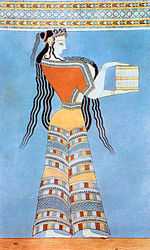

Athena (A-ta-na) appears in a Linear B inscription at Knossos from the Late Minoan II-era. The form A-ta-na po-ti-ni-ja (mistress Athena) is similar with the later Homeric form.[127] She was probably the goddess of the palace who is represented in the famous "Procession-fresco" at Knossos.[128] In a Mycenaean fresco, there is a composition of two women extending their hands towards a central figure who is covered by an enormous figure-eight shield. The central figure is the war-goddess with her palladium (classical antiquity), or her palladium in an aniconic representation.[107]

Dionysos (Di-wo-nu-so[129]) also appears in some inscriptions. His name is interpreted as "son of Zeus" and probably has a Thraco-Phrygian origin. Later his cult is related with Boeotia and Phocis, where it seems that was introduced before the end of the Mycenean age. This may explain why his myths and cult were centered in Thebes, and why the mountain Parnassos in Phocis was the place of his orgies. However, in the Homeric poems he is the consort of the Minoan vegetation goddess Ariadne.[130] He is the only Greek god other than Attis who dies in order to be reborn, as it often appears in the religions of the Orient.[131] His myth is related with the Minoan myth of the "divine child" who was abandoned by his mother and then brought up by the powers of nature. Similar myths appear in the cults of Hyakinthos (Amyklai), Erichthonios (Athens), and Ploutos (Eleusis).[132]

Other divinities who can be found in later periods have been identified, such as the couple Zeus–Hera, Hephaestus, Ares, Hermes, Eileithyia, and Erinya. Hephaestus, for example, is likely associated with A-pa-i-ti-jo at Knossos whereas Apollo is mentioned only if he is identified with Paiāwōn; Aphrodite, however, is entirely absent.[133] Qo-wi-ja ("cow-eyed") is a standard Homeric ephithet of Hera.[112] Ares has appeared under the name Enyalios (assuming that Enyalios is not a separate god) and though the importance of Areias is unknown, it does resemble the name of the god of war.[134] Eleuthia is associated with Eileithuia, the Homeric goddess of child-birth.[135]

There were some sites of importance for cults, such as Lerna, typically in the form of house sanctuaries since the free-standing temple containing a cult image in its cella with an open-air altar before it was a later development. Certain buildings found in citadels having a central room, the megaron, of oblong shape surrounded by small rooms may have served as places of worship. Aside from that, the existence of a domestic cult may be supposed. Some shrines have been located, as at Phylakopi on Melos, where a considerable number of statuettes discovered there were undoubtedly fashioned to serve as offerings, and it can be supposed from archaeological strata that sites such as Delphi, Dodona, Delos, Eleusis, Lerna, and Abae were already important shrines, and in Crete several Minoan shrines show continuity into LMIII, a period of Minoan-Mycenaean culture.

Architecture

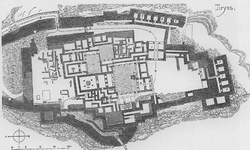

Fortresses

The principal Mycenaean towns were well fortified. The town could be situated on an acropolis as in Athens or Tiryns, against a large hill as in Mycenae, or on the coastal plain, like Gla or Pylos. Besides the citadels, there are also isolated forts that undoubtedly served to militarily control territory. Mycenaean walls were often made in a fashion called cyclopean, which means that they were constructed of large, unworked boulders up to eight meters (26 ft.) thick, loosely fitted without the clay mortar of the day. Different types of entrances or exits can be seen: monumental gates, access ramps, hidden doors, and vaulted galleries for escaping in case of a siege. Fear of attack meant that the chosen site must have a cistern or well at its disposal.

Habitations

The Mycenaean sites are composed of different types of residences. The smallest are rectangular in form and measure between 5 and 20 metres (16–66 ft.) on a side. These were the houses of the lowest classes. They could have one or several rooms; the latter become more widespread in more recent periods. On a more developed level are found larger residences, measuring about 20 to 35 meters (66 to 115 ft.) on a side, made up of many rooms and central courtyards. Their layout resembles that of a palace. It is not, however, certain that these were indeed the residences of the Mycenaean aristocrats; another theory is that they were palace annexes, being often situated next to them.

Palaces

The best examples of the Mycenaean palace are seen in the excavations at Mycenae, Tiryns, and Pylos. That these were administrative centers is shown by the records found there. From an architectural point of view, they were the heirs of the Minoan palaces and also of other palaces built on the Greek mainland during the Bronze Age. They were ranged around a group of courtyards each opening upon several rooms of different dimensions, such as storerooms and workshops, as well as reception halls and living quarters. The heart of the palace was the megaron. This was the throne room, laid out around a circular hearth surrounded by four columns, the throne generally being found on the right-hand side upon entering the room. The staircases found in the palace of Pylos indicate palaces had two stories. Located on the top floor were probably the private quarters of the royal family and some storerooms. These palaces have yielded a wealth of artifacts and fragmentary frescoes.

The most recent find is a Mycenaean palace near the village of Xirokambi, in Laconia. As of early 2009, the excavation is at its first stages and artifacts uncovered so far include clay vessels and figurines, frescoes and three Linear B tablets. Preliminary findings indicate that one of the tablets contains an inventory of about 500 daggers and another is an inventory for textiles. The discovery was announced at the Athens Archaeological Society on 28 April 2009.[136]

Architectural elements

Roof tiles

Contrary to an often held view, some Mycenaean representative buildings already featured roofs made of fired tiles, as in Gla and Midea.[137]

Art and craftwork

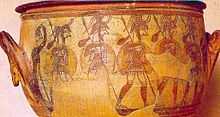

Vessels

The Mycenaeans made a great deal of pottery. Archaeologists have found a great quantity of pottery from the Mycenaean age, of widely diverse styles — stirrup jars, pitchers, kraters, chalices sometimes called "champagne coupes" after their shape, etc. The vessels vary greatly in size. Their conformations remained quite consistent throughout the Mycenaean period, up through LHIIIB, when production increased considerably, notably in Argolis whence came great numbers exported outside Greece. The products destined for export were generally more luxurious and featured heavily worked painted decorations incorporating mythic, warrior, or animal motifs. Another type of vessel, in metal (normally bronze), has been found in sizeable quantities at Mycenaean sites. The forms of these were tripods, basins, or lamps. A few examples of vessels in faience and ivory are also known.

Figures and figurines

The Mycenaean period has not yielded sculpture of any great size. The statuary of the period consists for the most part of small terracotta figurines found at almost every Mycenaean site in mainland Greece, in tombs, in settlement debris, and occasionally in cult contexts (Tiryns, Agios Konstantinos on Methana). The majority of these figurines are female and anthropomorphic or zoomorphic. The female figurines can be subdivided into three groups which were popular at different periods: the earliest are the Phi-type, which look like the Greek letter phi and their arms give the upper body of the figurine a rounded shape. The Psi-type looks like the letter Greek psi: these have outstretched upraised arms. The latest (12th century BC) are the Tau-type: these figurines look like the Greek letter tau with folded(?) arms at right angles to the body. Most figurines wear a large 'polos' hat.[138] They are painted with stripes or zigzags in the same manner as the contemporary pottery and presumably made by the same potters. Their purpose is uncertain, but they may have served as both votive objects and toys: some are found in children's graves but the vast majority of fragments are from domestic rubbish deposits.[139] The presence of many these figurines on sites where worship took place in the Archaic and Classical periods (circa 200 below the sanctuary of Athena at Delphi, others at the temple of Aphaia on Aegina, at the sanctuary of Apollo Maleatas above Epidauros and at Amyklae near Sparta), suggests both that many were indeed religious in nature, perhaps as votives, but also that later places of worship may well have first been used in the Mycenaean period.[140]

Larger male, female or bovine terracotta wheelmade figures are much rarer. An important group was found in the Temple at Mycenae together with coiled clay snakes,[141] while others have been found at Tiryns and in the East and West Shrines at Phylakopi on the island of Melos.[142]

Frescoes

The painting of the Mycenaean age was much influenced by that of the Minoan age. Fragments of wall paintings have been found in or around the palaces (Pylos, Mycenae, Tiryns) and in domestic contexts (Zygouries).[143] The largest complete wall painting depicting three female figures, probably goddesses, was found in the so-called Cult Centre at Mycenae.[144] Various themes are represented: hunting, bull leaping (tauromachy), battle scenes, processions, etc. Some scenes may be part of mythological narratives, but if so their meaning eludes us. Other frescoes include geometric or stylised motifs, also used on painted pottery (see above).

Arms

Military items have been found among the treasures of the Mycenaean age. The most impressive work is that of the Dendra panoply, a complete suit of Mycenaean armor and the oldest form of metal armor.[145] The cuirass is made up of bronze plates sewn to a leather garment. The weight of this armor must have hindered the mobility of a warrior, and it is for this reason it is supposed that it was worn by a warrior riding in a chariot.

The typical Mycenaean helmet, in use from the 17th to the 10th centuries BC,[146] was made of cut segments of boar's tusk sewn to a leather or cloth backing.[147] This type is illustrated in ivory relief plaques found in the shaft graves of the 17th and 16th centuries BC and in wall paintings of that era from Akrotiri on Thera (Santorini) and of the 13th century BC in the so-called Palace of Nestor at Pylos. Groups of boar's tusk plates from the helmets themselves have been found at many sites, including Mycenae, Prosymna, Thermon and Elateia, as well as in southern Italy. This is the type of helmet which is described by Homer several hundred years later.[148]

Offensive arms were made of bronze. Spears and javelins have been found, as well as an assortment of swords of different sizes designed for striking with the point and with the edge.[149] Daggers and arrows, attesting to the existence of archery, compose the remainder of the armament found from this period.[150]

As for defensive weapons, two types of shields were used by the Mycenaeans: the "figure eight" or "fiddle" shield,[151] and a rectangular type, the "tower" shield, rounded on the top.[152] They were made of wood and leather, and were of such a large size that if he wished to a warrior could crouch behind his shield and have his whole body covered.

Funerary practices

The usual form of burial in the Late Helladic was inhumation.[153] The dead were almost always buried in cemeteries outside the residential zones and only exceptionally within the settlements (the most famous burials in Grave Circle A originally lay outside the citadel and were only brought within it when the citadel wall was extended circa 1250 BC).

The earliest Mycenaean burials were mostly in individual graves in the form of a pit or a stone lined cist and offerings were limited to pottery and occasional items of jewellery. A large cemetery with burials of this kind spread around the northern and western slopes of the citadel at Mycenae.[154] Groups of pit or cist graves containing elite members of the community were sometimes covered by a tumulus (mound) in the manner established since the Middle Helladic period.[155] It has been argued that this form dates back to the oldest periods of Indo-European settlement in Greece, and that its roots are to be found in the Balkan cultures of the 3rd millennium BC, and even the Kurgan culture;[156] however, Mycenaean burials are in actuality an indigenous phenomenon/development of mainland Greece with the Shaft Graves housing native rulers.[157] Pit and cist graves remained in use for single burials throughout the Mycenaean period alongside more elaborate family graves (see below).[158]

The Shaft Graves at Mycenae within Grave Circles A and B belong to the same period and seem to represent an alternative manner of grouping elite or royal burials – and isolating them from those of the majority. Grave Circle B is the earlier of the two groups, already in use in the MH period, and contains lavish grave goods – gold and silver, jewellery, weapons and pottery. Circle A, excavated by Heinrich Schliemann, enclosed fewer but extraordinarily well provided graves.

Beginning also in the Late Helladic are to be seen communal tombs of rectangular form.[159] It is difficult to establish whether the different forms of burial represent a social hierarchization, as was formerly thought, with the tholoi being the tombs of the elite rulers, the individual tombs those of the leisure class, and the communal tombs those of the people. Cremations increased in number over the course of the period, becoming quite numerous in LHIIIC. The most impressive tombs of the Mycenaean era are the monumental royal tombs of Mycenae, undoubtedly intended for the royal family of the city. The most famous is the Treasury of Atreus, a tholos. Nearby are other tombs (known as "Circle A"), popularly identified with Clytemnestra and Aigisthos. All contained impressive treasures, exhumed by Schliemann during the excavation of Mycenae. It has been argued that different dynasties or factions may have competed through conspicuous burial, whereby grave circle A represents a new faction in the ascendancy (at this time, LHI, the relative wealth and consistency of 'B' burials declines).[160] The Mycenaean "tholoi" may, again, represent another factional grouping, or a further formalization in burial practices by the faction previously buried in A. Nevertheless, there is a demonstrably apparent expansion in relative size, wealth/cost expenditure, and visibility in the construction of these graves over this period, coinciding with increased foreign/trading contacts and the further entrenchment of the palatial economy.

See also

- Mycenae

- Mycenaean language

- Linear B

- Achaeans (Homer)

- Helladic

- Bronze Age

- Aegean civilizations

- Greek Dark Ages

- List of Mycenaean deities

References

Citations

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 Fields 2004, pp. 10–11.

- ↑ Hammond 1976, p. 139: "Moreover, in this area a small tholos-tomb with Mycenaean pottery of III B style and a Mycenaean acropolis have been reported at Kiperi near Parga, and another Mycenaean acropolis lay above the Oracle of the Dead on the hill called Xylokastro."

- ↑ Tandy 2001, p. xii (Fig. 1); p. 2: "The strongest evidence for Mycenaean presence in Epirus is found in the coastal zone of the lower Acheron River, which in antiquity emptied into a bay on the Ionian coast known from ancient sources as Glykys Limin (Figure 2-A)."

- ↑ Borza 1992, p. 64: "The existence of a Late Bronze Age Mycenaean settlement in the Petra not only confirms its importance as a route from an early period, but also extends the limits of Mycenaean settlement to the Macedonian frontier."

- ↑ Aegeo-Balkan Prehistory – Mycenaean Sites

- ↑ van Wijngaarden 2002, Part II: The Levant, pp. 31–124; Bietak & Czerny 2007, Sigrid Deger-Jalkotzy, "Mycenaeans and Philistines in the Levant", pp. 501–629.

- ↑ van Wijngaarden 2002, Part III: Cyprus, pp. 125–202.

- ↑ Peruzzi 1980; van Wijngaarden 2002, Part IV: The Central Mediterranean, pp. 203–260.

- ↑ The extent to which Homer attempted to or succeeded in recreating a "Mycenaean" setting is examined in Moses I. Finley The World of Odysseus, 1954.

- ↑ Chadwick 1976, p. 617.

- ↑ Latacz 2004, pp. 159, 165.

- ↑ Latacz 2004, p. 120.

- ↑ Latacz 2004, p. 138.

- ↑ Hajnal & Posch 2009, pp. 1–2.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Kelder 2010, pp. 46–47.

- ↑ Kelder 2010, pp. 37–38; Latacz 2004, p. 159.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Beckman, Bryce & Cline 2012, p. 4.

- ↑ Latacz 2004, p. 123.

- ↑ Bryce 2005, p. 58.

- ↑ Latacz 2004, p. 122.

- ↑ Bryce 2005, p. 357.

- ↑ Dickinson 1977, pp. 32, 53, 107–108; Dickinson 1999, pp. 97–107.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 23.3 Schofield 2006, p. 31.

- ↑ Dickinson 1977, pp. 32, 53, 107–108; Dickinson 1999, pp. 97–107.

- ↑ Schofield 2006, p. 51.

- ↑ Schofield 2006, p. 48.

- ↑ Schofield 2006, p. 32.

- ↑ Dickinson 1977, pp. 53, 107.

- ↑ Schofield 2006, p. 67.

- ↑ Schofield 2006, pp. 64–68.

- ↑ Castleden 2005, p. 97; Schofield 2006, p. 55.

- ↑ Chadwick 1976, p. 12.

- ↑ Tartaron 2013, p. 28.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 34.2 Schofield 2006, pp. 71–72.

- ↑ Schofield 2006, p. 75.

- ↑ Kelder 2010, p. 8.

- ↑ Tartaron 2013, p. 21.

- ↑ Kelder 2010, pp. 50, 52.

- ↑ Bryce 2005, p. 361.

- ↑ Castleden 2005, p. 194: "The Mycenaean colonies in Anatolia were emphatically confined to a narrow coastal strip in the west. There were community-colonies at Ephesus, Iasos and Miletus, but they had little effect on the interior..."

- ↑ Kelder 2010, p. 107.

- ↑ Kelder 2010, pp. 108–109.

- ↑ Kelder 2010, p. 11; Fields 2004, p. 53.

- ↑ Bryce 2005, p. 361.

- ↑ Beckman, Bryce & Cline 2012, p. 6.

- ↑ Kelder 2010, pp. 119–120.

- ↑ Bryce 2005, p. 59; Kelder 2010, p. 23.

- ↑ Bryce 2005, p. 59.

- ↑ Bryce 2005, pp. 129, 368.

- ↑ Bryce 2005, p. 193.

- ↑ Kelder 2010, p. 26.

- ↑ Bryce 2005, p. 58; Kelder 2010, pp. 119–120.

- ↑ Bryce 2005, p. 224.

- ↑ 54.0 54.1 Kelder 2010, p. 27.

- ↑ Bryce 2005, pp. 361, 364.

- ↑ Bryce 2005, p. 290.

- ↑ Kelder 2010, p. 34.

- ↑ Cline 2014, p. 130.

- ↑ 59.0 59.1 Castleden 2005, p. 219.

- ↑ 60.0 60.1 60.2 60.3 60.4 60.5 60.6 Freeman 2014, p. 126.

- ↑ Kelder 2010, p. 33.

- ↑ Kelder 2010, p. 32.

- ↑ Tartaron 2013, p. 20.

- ↑ Cline 2014, p. 130.

- ↑ Cline 2014, p. 129.

- ↑ 66.0 66.1 Tartaron 2013, p. 18.

- ↑ Mylonas 1966, pp. 227–228.

- ↑ Mylonas 1966, pp. 231–232.

- ↑ Drews 1993, p. 49.

- ↑ 70.0 70.1 Tartaron 2013, p. 19.

- ↑ Freeman 2014, p. 127.

- ↑ 72.0 72.1 72.2 Kelder 2010, p. 9.

- ↑ Kelder 2010, p. 34.

- ↑ Kelder 2010, p. 97.

- ↑ Kelder 2010, pp. 8–9.

- ↑ 76.0 76.1 >Beckman, Bryce & Cline 2012, p. 6.

- ↑ Kelder 2010, pp. 45, 86, 107.

- ↑ Kelder 2010, pp. 86–87.

- ↑ Thomas 1995, p. 350.

- ↑ 80.0 80.1 Kelder 2010, p. 8.

- ↑ 81.0 81.1 81.2 81.3 81.4 Chadwick 1976, Chapter 5: Social Structure and Administrative System, pp. 69–83.

- ↑ 82.0 82.1 82.2 Kelder 2010, p. 11.

- ↑ Fields 2004, p. 57.

- ↑ Chadwick 1976, pp. 71–72.

- ↑ δῆμος. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; An Intermediate Greek-English Lexicon at the Perseus Project.

- ↑ δοῦλος. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; A Greek–English Lexicon at the Perseus Project.

- ↑ Castleden 2005.

- ↑ Boston University – The Historical Society

- ↑ Amber object bearing Linear B symbols from the Freising district of Germany, excavations in the years 1994–1997.

- ↑ Budin 2009, p. 53: "One of the most extraordinary examples of the extent of Mycenaean influence was the Pelynt Dagger, a fragment of a Late Helladic III sword, which has come to light in the tomb of a Wessex chieftain in southern England!"

- ↑ Feuer 2004, p. 259.

- ↑ Feuer 2004, pp. 155–157; Balmuth & Tykot 1998, "The Mycenaeans in Sardinia", p. 400; Runnels & Murray 2004, p. 15.

- ↑ Ridgway 1992, p. 4; Taylour 1958; Fisher 1998; Runnels & Murray 2001, p. 15; Vianello 2005, "Eastern Sicily and the Aeolian Islands", p. 51; Feuer 2004, pp. 155–157; van Wijngaarden 2002, Part IV: The Central Mediterranean, pp. 203-260.

- ↑ Runnels & Murray 2001, p. 15.

- ↑ Kling 1989; Nikolaou 1973; International Archaeological Symposium 1973.

- ↑ Stubbings 1951, IV: Mycenaean II Pottery in Syria and Palestine; V: Mycenaean III Pottery in Syria and Palestine.

- ↑ Petrie 1894.

- ↑ de la Cruz 1988, pp. 77–92; Ridgway 1992, p. 3; Runnels & Murray 2001, p. 15.

- ↑ Chadwick 1976, p. 88.

- ↑ As explicitly expressed in Martin P. Nilsson, The Minoan-Mycenaean Religion and Its Survival in Greek Religion, 1927.

- ↑ Chadwick 1976, p. 84.

- ↑ Chadwick 1976, p. 87: "Words that are not understood are constantly deformed to give them meanings. Mere resemblance is of course nearly always deceptive."

- ↑ Finley 1954.

- ↑ Nilsson 1967, Volume I, p. 339.

- ↑ Paul, Adams John (10 January 2010). "Mycenaean Divinities". Northridge, CA: California State University. Retrieved 25 September 2013.

- ↑ Nilsson 1940.

- ↑ 107.0 107.1 107.2 Mylonas 1966, p. 159.

- ↑ Chadwick 1976, pp. 92–93.

- ↑ Mylonas 1966, p. 159: "Wa-na-ssoi, wa-na-ka-te, (to the two queens and the king). Wanax is best suited to Poseidon, the special divinity of Pylos. The identity of the two divinities addressed as wanassoi, is uncertain."

- ↑ Chadwick 1976, p. 76.

- ↑ Nilsson 1967, Volume I, p. 463.

- ↑ 112.0 112.1 Chadwick 1976, p. 95.

- ↑ Eustathius of Thessalonica, scholia on Homer, 265.

- ↑ Mylonas 1961.

- ↑ Nilsson 1967, Volume I, p. 475.

- ↑ Pausanias. Description of Greece, VIII-25.4, VIII-37.1ff, VIII.42.

- ↑ Nilsson 1967, Volume I, pp. 479–480.

- ↑ Robertson 1959, p. 31; National Archaeological Museum of Athens, No. 2665.

- ↑ Nilsson 1967, Volume I, p. 293.

- ↑ Nilsson 1967, Volume I, pp. 227, 297.

- ↑ Pausanias. Description of Greece, VIII-37.6.

- ↑ Chadwick & Baumbach 1963, p. 176f.

- ↑ Nilsson 1967, Volume I, pp. 273, 295.

- ↑ Nilsson 1967, Volume I, pp. 162, 310, 489.

- ↑ Nilsson 1967, Volume I, pp. 281, 283, 301, 487.

- ↑ Nilsson 1967, Volume I, pp. 500–504; Chadwick 1976, p. 88: "Pa-ja-wo suggested Homeric Paieon, which earlier would have been Paiawon, later Paidn, an alternative name of Apollo, if not again a separate god."

- ↑ Kn V 52 (text 208 in Ventris and Chadwick); Chadwick 1976, p. 88.

- ↑ Hagg & Wells 1978, Arne Furumark, "Aegean Society", p. 14: "Atano is identical with the Greek Athana (that she was originally the Minoan "palace goddess" was rightly concluded long ago by Martin P. Nilsson)."

- ↑ Palaeolexicon. "di-wo-nu-so".

- ↑ Nilsson 1967, Volume I, pp. 565–568.

- ↑ Nilsson 1967, Volume I, p. 215.

- ↑ Nilsson 1967, Volume I, pp. 215–219.

- ↑ Chadwick 1976, p. 99.

- ↑ Chadwick 1976, pp. 95, 99.

- ↑ Chadwick 1976, p. 98.

- ↑ Ταράντου, Σοφία (28 April 2009). "Βρήκαν μυκηναϊκό ανάκτορο". Ethnos.gr. Retrieved 25 September 2013.

- ↑ Wikander 1990, p. 288; Shear 2000, p. 134.

- ↑ French 1971, pp. 101–187.

- ↑ See account of their use in K.A. and Diana Wardle "The Child's Cache at Assiros, Macedonia", in Sally Crawford and Gillian Shepherd (eds): Children, Childhood and Society: Institute for Archaeology and Antiquity Interdisciplinary Studies (Volume I) Oxford: Archaeopress, 2007.

- ↑ Hägg & Marinatos 1981, Robin Hägg, "Official and Popular Cults in Mycenaean Greece", pp. 35–39.

- ↑ Moore, Taylour & French 1999.

- ↑ Renfrew, Mountjoy & Macfarlane 1985.

- ↑ Immerwahr 1990.

- ↑ Taylour 1969, pp. 91–97; Taylour 1970, pp. 270–280.

- ↑ Modern Reconstruction of the Dendra Panoply.

- ↑ Wardle & Wardle 1997, p. 65 (Fig. 21); pp. 69–70.

- ↑ Mycenaean Helmet.

- ↑ Homer. The Iliad, 10.260–10.265.

- ↑ Mycenaean Swords; Mycenaean Type G Sword (Horn Sword).

- ↑ Mycenaean Dagger.

- ↑ Mycenaean "Figure Eight" Shield, Fresco.

- ↑ Mycenaean Tower Shield, Drawing.

- ↑ Cavanagh & Mee 1998.

- ↑ Taylour, French & Wardle 2007; Alden 2000.

- ↑ Pelon 1976.

- ↑ Hammond 1967, p. 90.

- ↑ Dickinson 1977, pp. 33–34, 53, 59–60.

- ↑ Lewartowski 2000.

- ↑ Papadimitriou 2001.

- ↑ See Graziado 1991 for a more comprehensive discussion of these trends, in addition to a sophisticated study of the grave goods in particular burials.

Sources

- Alden, Maureen Joan (2000). Well Built Mycenae (Volume 7): The Prehistoric Cemetery - pre-Mycenaean and Early Mycenaean Graves. Oxford: Oxbow Books. ISBN 978-1-84-217018-2.

- Balmuth, Miriam S.; Tykot, Robert H. (1998). Studies in Sardinian Archaeology, Volume 5. Ann Arbor, MI: Oxbow Books.

- Beckman, Gary M.; Bryce, Trevor R.; Cline, Eric H. (2012). Writings from the Ancient World: The Ahhiyawa Texts (PDF). Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature. ISSN 1570-7008.

- Borza, Eugene N. (1992). In the Shadow of Olympus: The Emergence of Macedon. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-00880-6.

- Bryce, Trevor (2005). The Kingdom of the Hittites (New Edition ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199279081.

- Budin, Stephanie Lynn (2009) [2004]. The Ancient Greeks: An Introduction. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-537984-6.

- Castleden, Rodney (2005). The Mycenaeans. London and New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-36336-5.

- Cavanagh, William G.; Mee, Christopher (1998). A Private Place: Death in Prehistoric Greece [SIMA 125]. Jonsered: Paul Aströms Förlag. ISBN 978-9-17-081178-4.

- Chadwick, John; Baumbach, Lydia (1963). "The Mycenaean Greek Vocabulary". Glotta (Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht (GmbH & Co. KG)) 41 (3/4): 157–271.

- Chadwick, John (1976). The Mycenaean World. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-29037-6.

- Cline, Eric H. (2014). 1177 B.C. The Year Civilization Collapsed. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 9781400849987.

- de la Cruz, José Clemente Martín (1988). "Mykenische Keramik aus Bronzezeitlichen Siedlungsschichten von Montoro am Guadalquivir". Madrider Mitteilungen (29): 77–92.

- Dickinson, Oliver (1977). The Origins of Mycenaean Civilization. Götenberg: Paul Aströms Förlag.

- Dickinson, Oliver (December 1999). Invasion, Migration and the Shaft Graves. Bulletin of the Institute of Classical Studies 43 (1). pp. 97–107. doi:10.1111/j.2041-5370.1999.tb00480.x.

- Dickinson, Oliver (2006). The Aegean from Bronze Age to Iron Age: Continuity and Change between the Twelfth and Eighth Centuries BC. New York, NY: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-20-396836-9.

- Drews, Robert (1993). The End of the Bronze Age. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-69-102591-9.

- Feuer, Bryan Avery (2004). Mycenaean Civilization: An Annotated Bibliography through 2002. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, Inc. ISBN 978-0-78-641748-3.

- Fields, Nic; illustrated by Donato Spedaliere (2004). Mycenaean Citadels c. 1350–1200 BC (3rd Edition ed.). Oxford: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 9781841767628.

- Finley, Moses I. (1954). The World of Odysseus. New York, NY: New York Review Books. ISBN 978-1-59-017017-5.

- Fisher, Elizabeth A. (1998). The Mycenaeans and Apulia. An Examination of Aegean Bronze Age Contacts with Apulia in Eastern Magna Grecia. Jonsered, Sweden: Astrom.

- Freeman, Charles (2014). Egypt, Greece and Rome: Civilizations of the Ancient Mediterranean (3rd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199651924.

- Graziado, Giampaolo (July 1991). "The Process of Social Stratification at Mycenae in the Shaft Grave Period: A Comparative Examination of the Evidence". American Journal of Archaeology (Archaeological Institute of America) 95 (3): 403–440.

- Hajnal, Ivo; Posch, Claudia (2009). "Graeco-Anatolian Contacts in the Mycenaean Period". Sprachwissenschaft Innsbruck Institut für Sprachen und Literaturen. Retrieved 4 April 2015.

- Hammond, Nicholas G.L. (1967). "Tumulus Burial in Albania, the Grave Circles of Mycenae, and the Indo-Europeans". Annual of the British School at Athens 62.

- Hagg, Robin; Wells, Berit (1978). Opuscula Atheniensia XII. Lund: Paul Astroms Forlag. ISBN 978-9-18-508612-2.

- Hägg, Robin; Marinatos, Nannó (1981). Sanctuaries and Cults in the Aegean Bronze Age: Proceedings of the First International Symposium at the Swedish Institute in Athens, 12-13 May, 1980. Stockholm: Svenska Institutet i Athen. ISBN 978-9-18-508643-6.

- Hammond, Nicholas G.L. (1976). Migrations and Invasions in Greece and Adjacent Areas. Park Ridge, NJ: Noyes Press. ISBN 978-0-8155-5047-1.

- Immerwahr, Sara A. (1990). Aegean Painting in the Bronze Age. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 978-0-27-100628-4.

- Latacz, Joachim (2004). Troy and Homer: Towards a Solution of an Old Mystery. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199263080.

- Kelder, Jorrit M. (2010). "The Kingdom of Mycenae: A Great Kingdom in the Late Bronze Age Aegean". www.academia.edu. Bethesda, MD: CDL Press. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- Kling, Barbara (1989). Mycenaean IIIC:1b and Related Pottery in Cyprus. Lund: P. Aströms Förlag. ISBN 978-9-18-609893-3.

- Lewartowski, Kazimierz (2000). Late Helladic Simple Graves: A Study of Mycenaean Burial Customs (BAR International Series 878). Oxford: Archaeopress. ISBN 978-1-84-171079-2.

- Moore, A.D.; Taylour, W.D.; French, Elizabeth Bayard (1999). Well Built Mycenae (Volume 10): The Temple Complex. Warminster, England: Aris & Phillips. ISBN 978-1-84-217000-7.

- Mylonas, George Emmanuel (1961). Eleusis and the Eleusinian Mysteries. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Mylonas, George Emmanuel (1966). Mycenae and the Mycenaean Age. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Nikolaou, Kyriakos (1973). The First Myceneans in Cyprus. Nicosia: Department of Antiquities, Cyprus.

- Nilsson, Martin Persson (1940). Greek Popular Religion. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Nilsson, Martin Persson (1967). Geschichte der Griechischen Religion (3rd ed.). Munich: C.H. Beck Verlag.

- Papadimitriou, Nikolas (2001). Built Chamber Tombs of Middle and Late Bronze Age Date in Mainland Greece and the Islands (BAR International Series 925). Oxford: John and Erica Hedges Ltd. and Archaeopress. ISBN 978-1-84-171170-6.

- Pelon, Olivier (1976). Tholoi, Tumuli et Cercles Funéraires. Paris: Diffusion de Boccard.

- Peruzzi, Emilio (1980). Mycenaeans in Early Latium. Rome: Edizioni dell'Ateneo & Bizzarri.

- Petrie, Sir William Matthew Flinders (1894). Tell el-Amarna. London: Methuen & Co.

- Renfrew, Colin; Mountjoy, Penelope A.; Macfarlane, Callum (1985). The Archaeology of Cult: The Sanctuary at Phylakopi. London: British School of Archaeology at Athens. ISBN 978-0-50-096021-9.

- Ridgway, David (1992). The First Western Greeks. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-52-142164-5.

- Robertson, Martin (1959). Les Grands siècles de la peinture: La peinture Grecque. Genève-Paris: Skira.

- Runnels, Curtis Neil; Murray, Priscilla (2001). Greece before History: An Archaeological Companion and Guide. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-4050-0.

- Shear, Ione Mylonas (January 2000). "Excavations on the Acropolis of Midea: Results of the Greek–Swedish Excavations under the Direction of Katie Demakopoulou and Paul Åström". American Journal of Archaeology 104 (1): 133–134.

- Schofield, Louise (2006). The Mycenaeans. Los Angeles, CA: J. Paul Getty Museum. ISBN 9780892368679.

- Stubbings, Frank H. (1951). Mycenaean Pottery from the Levant. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Tandy, David W. (2001). Prehistory and History: Ethnicity, Class and Political Economy. Montréal, Québec, Canada: Black Rose Books Limited. ISBN 1-55164-188-7.

- Tartaron, Thomas F. (2013). Maritime Networks in the Mycenaean World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107067134.

- Taylour, Lord William; French, Elizabeth Bayard; Wardle, K.A. (2007). Well Built Mycenae (Volume 13): The Helleno-British Excavations within the Citadel at Mycenae 1959-1969. Warminster, England: Aris & Phillips. ISBN 978-1-84-217295-7.

- Taylour, Lord William (1969). "Mycenae, 1968". Antiquity 43: 91–97.

- Taylour, Lord William (1970). "New Light on Mycenaean Religion". Antiquity 44: 270–280.

- Taylour, Lord William (1958). Mycenaean Pottery in Italy and Adjacent Areas. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Thomas, Carol G. (1995). "The Components of Political Identity in Mycenaean Greece" (PDF). Aegaeum 12: 349–354.

- van Wijngaarden, Geert Jan (2002). Use and Appreciation of Mycenaean Pottery in the Levant, Cyprus and Italy (1600–1200 BC). Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. ISBN 978-9-05-356482-0.

- Vianello, Andrea (2005). Late Bronze Age Mycenaean and Italic Products in the West Mediterranean: A Social and Economic Analysis. Oxford: Archaeopress. ISBN 978-1-84-171875-0.

- Wardle, K.A.; Wardle, Diana (1997). Cities of Legend: The Mycenaean World. London: Bristol Classical Press. ISBN 978-1-85-399355-8.

- Wikander, Örjan (January–March 1990). "Archaic Roof Tiles the First Generations". Hesperia 59 (1): 285–290. doi:10.2307/148143.

Further reading

- Barlow, Jane Atwood; Bolger, Diane L.; Kling, Barbara (1991). Cypriot Ceramics: Reading the Prehistoric Record. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology. ISBN 978-0-92-417110-9.

- Burkert, Walter (1987) [1985]. Greek Religion: Archaic and Classical. Oxford and Malden: Blackwell Publishing Limited. ISBN 978-1-11-872499-6.

- Doumas, Christos (1980). Thera and the Aegean World II: Papers Presented at the Second International Scientific Congress, Santorini, Greece, August 1978. London: Thera and the Aegean World. ISBN 978-0-95-061332-1.

- French, Elizabeth Bayard (2002). Mycenae: Agamemnon's Capital. Stroud: Tempus. ISBN 0-7524-1951-X.

- Gitin, Seymour; Mazar, Amihay; Stern, Ephraim; Dothan, Trude Krakauer (1998). Mediterranean Peoples in Transition: Thirteenth to Early Tenth Centuries BCE. Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society. ISBN 978-9-65-221036-4.

- Güterbock, Hans G. (April 1983). "The Hittites and the Aegean World: Part 1. The Ahhiyawa Problem Reconsidered". American Journal of Archaeology 87 (2): 133–138.

- Güterbock, Hans G. (June 1984). "Hittites and Akhaeans: A New Look". Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 128 (2): 114–122.

- Hänsel, B. (ed.); Podzuweit, Christian (1982). "Die mykenische Welt und Troja". Südosteuropa zwischen 1600 und 1000 V. Chr. (in German). Berlin: Moreland Editions. pp. 65–88.

- Higgins, Reynold Alleyne (1997). Minoan and Mycenaean Art. London and New York: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-50-020303-3.

- Hooker, J.T. (1976). Mycenaean Greece. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- Huxley, G.L. (1960). Achaeans and Greeks. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press.

- Mellink, Machteld J. (April 1983). "The Hittites and the Aegean World: Part 2. Archaeological Comments on Ahhiyawa-Achaians in Western Anatolia". American Journal of Archaeology 87 (2): 138–141.

- Mountjoy, Penelope A. (1986). Mycenaean Decorated Pottery: A Guide to Identification (Studies in Mediterranean Archaeology 73). Göteborg: Paul Aströms Forlag. ISBN 978-9-18-609832-2.

- Nur, Amos; Cline, Eric (2000). "Poseidon's Horses: Plate Tectonics and Earthquake Storms in the Late Bronze Age Aegean and Eastern Mediterranean" (PDF). Journal of Archaeological Science 27 (1): 43–63. doi:10.1006/jasc.1999.0431.

- Preziosi, Donald; Hitchcock, Louise A. (1999). Aegean Art and Architecture. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-284208-4.

- Skeat, T.C. (1934). The Dorians in Archaeology. London: de la More Press.

- Taylour, Lord William (1990) [1964]. The Mycenaeans. London: Thames & Hudson Limited. ISBN 978-0-50-027586-3.

- Vermeule, Emily; Karageorghis, Vassos (1982). Mycenaean Pictorial Vase Painting. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-67-459650-4.

- Vermeule, Emily Townsend (March 1960). "The Fall of the Mycenaean Empire". Archaeology (Archaeological Institute of America) 13 (1): 66–76. doi:10.2307/41663738.

- Weiss, Barry (June 1982). "The Decline of Late Bronze Age Civilization as a Possible Response to Climatic Change". Climatic Change 4 (2): 173–198. doi:10.1007/bf00140587. ISSN 0165-0009.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mycenaean culture. |

- Godart, Louis (2013) [January 1997]. "Les citadelles mycéniennes" (in French). Clio.

- Hemingway, Seán; Hemingway, Colette (2000–2013). "Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History: Mycenaean Civilization". The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- Horejs, Barbara; Pavúk, Peter, eds. (2007). "The Aegeo-Balkan Prehistory Project". The Aegeo-Balkan Prehistory Team.

- Rutter, Jeremy B. "Prehistoric Archeology of the Aegean". Hanover, NH: Dartmouth College.

- Salimbetti, Andrea (30 September 2013). "The Greek Age of Bronze".

- "The Mycenaeans and Italy: The Archaeological and Archaeometric Ceramic Evidence". University of Glasgow School of Humanities.

- Wright, James C. (2002). "The Nemea Valley Archaeological Project: Internet Edition". Bryn Mawr College Department of Classical and Near Eastern Archaeology.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||