Multicollinearity

In statistics, multicollinearity (also collinearity) is a phenomenon in which two or more predictor variables in a multiple regression model are highly correlated, meaning that one can be linearly predicted from the others with a non-trivial degree of accuracy. In this situation the coefficient estimates of the multiple regression may change erratically in response to small changes in the model or the data. Multicollinearity does not reduce the predictive power or reliability of the model as a whole, at least within the sample data set; it only affects calculations regarding individual predictors. That is, a multiple regression model with correlated predictors can indicate how well the entire bundle of predictors predicts the outcome variable, but it may not give valid results about any individual predictor, or about which predictors are redundant with respect to others.

In case of perfect multicollinearity the predictor matrix is singular and therefore cannot be inverted. Under these circumstances, the ordinary least-squares estimator  does not exist.

does not exist.

Note that in statements of the assumptions underlying regression analyses such as ordinary least squares, the phrase "no multicollinearity" is sometimes used to mean the absence of perfect multicollinearity, which is an exact (non-stochastic) linear relation among the regressors.

Definition

Collinearity is a linear association between two explanatory variables. Two variables are perfectly collinear if there is an exact linear relationship between them. For example,  and

and  are perfectly collinear if there exist parameters

are perfectly collinear if there exist parameters  and

and  such that, for all observations i, we have

such that, for all observations i, we have

Multicollinearity refers to a situation in which two or more explanatory variables in a multiple regression model are highly linearly related. We have perfect multicollinearity if, for example as in the equation above, the correlation between two independent variables is equal to 1 or -1. In practice, we rarely face perfect multicollinearity in a data set. More commonly, the issue of multicollinearity arises when there is an approximate linear relationship among two or more independent variables.

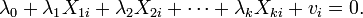

Mathematically, a set of variables is perfectly multicollinear if there exist one or more exact linear relationships among some of the variables. For example, we may have

holding for all observations i, where  are constants and

are constants and  is the ith observation on the jth explanatory variable. We can explore one issue caused by multicollinearity by examining the process of attempting to obtain estimates for the parameters of the multiple regression equation

is the ith observation on the jth explanatory variable. We can explore one issue caused by multicollinearity by examining the process of attempting to obtain estimates for the parameters of the multiple regression equation

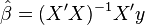

The ordinary least squares estimates involve inverting the matrix

where

If there is an exact linear relationship (perfect multicollinearity) among the independent variables, the rank of X (and therefore of XTX) is less than k+1, and the matrix XTX will not be invertible.

In most applications, perfect multicollinearity is unlikely. An analyst is more likely to face a high degree of multicollinearity. For example, suppose that instead of the above equation holding, we have that equation in modified form with an error term  :

:

In this case, there is no exact linear relationship among the variables, but the  variables are nearly perfectly multicollinear if the variance of

variables are nearly perfectly multicollinear if the variance of  is small for some set of values for the

is small for some set of values for the  's. In this case, the matrix XTX has an inverse, but is ill-conditioned so that a given computer algorithm may or may not be able to compute an approximate inverse, and if it does so the resulting computed inverse may be highly sensitive to slight variations in the data (due to magnified effects of rounding error) and so may be very inaccurate.

's. In this case, the matrix XTX has an inverse, but is ill-conditioned so that a given computer algorithm may or may not be able to compute an approximate inverse, and if it does so the resulting computed inverse may be highly sensitive to slight variations in the data (due to magnified effects of rounding error) and so may be very inaccurate.

Detection of multicollinearity

Indicators that multicollinearity may be present in a model:

- Large changes in the estimated regression coefficients when a predictor variable is added or deleted

- Insignificant regression coefficients for the affected variables in the multiple regression, but a rejection of the joint hypothesis that those coefficients are all zero (using an F-test)

- If a multivariable regression finds an insignificant coefficient of a particular explanator, yet a simple linear regression of the explained variable on this explanatory variable shows its coefficient to be significantly different from zero, this situation indicates multicollinearity in the multivariable regression.

- Some authors have suggested a formal detection-tolerance or the variance inflation factor (VIF) for multicollinearity:

where is the coefficient of determination of a regression of explanator j on all the other explanators. A tolerance of less than 0.20 or 0.10 and/or a VIF of 5 or 10 and above indicates a multicollinearity problem.[1]

is the coefficient of determination of a regression of explanator j on all the other explanators. A tolerance of less than 0.20 or 0.10 and/or a VIF of 5 or 10 and above indicates a multicollinearity problem.[1] - Condition number test: The standard measure of ill-conditioning in a matrix is the condition index. It will indicate that the inversion of the matrix is numerically unstable with finite-precision numbers ( standard computer floats and doubles ). This indicates the potential sensitivity of the computed inverse to small changes in the original matrix. The Condition Number is computed by finding the square root of (the maximum eigenvalue divided by the minimum eigenvalue). If the Condition Number is above 30, the regression is said to have significant multicollinearity.

- Farrar–Glauber test:[2] If the variables are found to be orthogonal, there is no multicollinearity; if the variables are not orthogonal, then multicollinearity is present. C. Robert Wichers has argued that Farrar–Glauber partial correlation test is ineffective in that a given partial correlation may be compatible with different multicollinearity patterns.[3] The Farrar–Glauber test has also been criticized by other researchers.[4][5]

- Construction of a correlation matrix among the explanatory variables will yield indications as to the likelihood that any given couplet of right-hand-side variables are creating multicollinearity problems. Correlation values (off-diagonal elements) of at least .4 are sometimes interpreted as indicating a multicollinearity problem.

Consequences of multicollinearity

One consequence of a high degree of multicollinearity is that, even if the matrix XTX is invertible, a computer algorithm may be unsuccessful in obtaining an approximate inverse, and if it does obtain one it may be numerically inaccurate. But even in the presence of an accurate XTX matrix, the following consequences arise.

In the presence of multicollinearity, the estimate of one variable's impact on the dependent variable  while controlling for the others tends to be less precise than if predictors were uncorrelated with one another. The usual interpretation of a regression coefficient is that it provides an estimate of the effect of a one unit change in an independent variable,

while controlling for the others tends to be less precise than if predictors were uncorrelated with one another. The usual interpretation of a regression coefficient is that it provides an estimate of the effect of a one unit change in an independent variable,  , holding the other variables constant. If

, holding the other variables constant. If  is highly correlated with another independent variable,

is highly correlated with another independent variable,  , in the given data set, then we have a set of observations for which

, in the given data set, then we have a set of observations for which  and

and  have a particular linear stochastic relationship. We don't have a set of observations for which all changes in

have a particular linear stochastic relationship. We don't have a set of observations for which all changes in  are independent of changes in

are independent of changes in  , so we have an imprecise estimate of the effect of independent changes in

, so we have an imprecise estimate of the effect of independent changes in  .

.

In some sense, the collinear variables contain the same information about the dependent variable. If nominally "different" measures actually quantify the same phenomenon then they are redundant. Alternatively, if the variables are accorded different names and perhaps employ different numeric measurement scales but are highly correlated with each other, then they suffer from redundancy.

One of the features of multicollinearity is that the standard errors of the affected coefficients tend to be large. In that case, the test of the hypothesis that the coefficient is equal to zero may lead to a failure to reject a false null hypothesis of no effect of the explanator, a type II error.

A principal danger of such data redundancy is that of overfitting in regression analysis models. The best regression models are those in which the predictor variables each correlate highly with the dependent (outcome) variable but correlate at most only minimally with each other. Such a model is often called "low noise" and will be statistically robust (that is, it will predict reliably across numerous samples of variable sets drawn from the same statistical population).

So long as the underlying specification is correct, multicollinearity does not actually bias results; it just produces large standard errors in the related independent variables. More importantly, the usual use of regression is to take coefficients from the model and then apply them to other data. If the pattern of multicollinearity in the new data differs from that in the data that was fitted, such extrapolation may introduce large errors in the predictions.[6]

Remedies for multicollinearity

- Make sure you have not fallen into the dummy variable trap; including a dummy variable for every category (e.g., summer, autumn, winter, and spring) and including a constant term in the regression together guarantee perfect multicollinearity.

- Try seeing what happens if you use independent subsets of your data for estimation and apply those estimates to the whole data set. Theoretically you should obtain somewhat higher variance from the smaller datasets used for estimation, but the expectation of the coefficient values should be the same. Naturally, the observed coefficient values will vary, but look at how much they vary.

- Leave the model as is, despite multicollinearity. The presence of multicollinearity doesn't affect the efficacy of extrapolating the fitted model to new data provided that the predictor variables follow the same pattern of multicollinearity in the new data as in the data on which the regression model is based.[7]

- Drop one of the variables. An explanatory variable may be dropped to produce a model with significant coefficients. However, you lose information (because you've dropped a variable). Omission of a relevant variable results in biased coefficient estimates for the remaining explanatory variables that are correlated with the dropped variable.

- Obtain more data, if possible. This is the preferred solution. More data can produce more precise parameter estimates (with lower standard errors), as seen from the formula in variance inflation factor for the variance of the estimate of a regression coefficient in terms of the sample size and the degree of multicollinearity.

- Mean-center the predictor variables. Generating polynomial terms (i.e., for

,

,  ,

,  , etc.) can cause some multicollinearity if the variable in question has a limited range (e.g., [2,4]). Mean-centering will eliminate this special kind of multicollinearity. However, in general, this has no effect. It can be useful in overcoming problems arising from rounding and other computational steps if a carefully designed computer program is not used.

, etc.) can cause some multicollinearity if the variable in question has a limited range (e.g., [2,4]). Mean-centering will eliminate this special kind of multicollinearity. However, in general, this has no effect. It can be useful in overcoming problems arising from rounding and other computational steps if a carefully designed computer program is not used. - Standardize your independent variables. This may help reduce a false flagging of a condition index above 30.

- It has also been suggested that using the Shapley value, a game theory tool, the model could account for the effects of multicollinearity. The Shapley value assigns a value for each predictor and assesses all possible combinations of importance.[8]

- Ridge regression or principal component regression can be used.

- If the correlated explanators are different lagged values of the same underlying explanator, then a distributed lag technique can be used, imposing a general structure on the relative values of the coefficients to be estimated.

Note that one technique that does not work in offsetting the effects of multicollinearity is orthogonalizing the explanatory variables (linearly transforming them so that the transformed variables are uncorrelated with each other): By the Frisch–Waugh–Lovell theorem, using projection matrices to make the explanatory variables orthogonal to each other will lead to the same results as running the regression with all non-orthogonal explanators included.

Examples of contexts in which multicollinearity arises

Survival analysis

Multicollinearity may represent a serious issue in survival analysis. The problem is that time-varying covariates may change their value over the time line of the study. A special procedure is recommended to assess the impact of multicollinearity on the results.[9]

Interest rates for different terms to maturity

In various situations it might be hypothesized that multiple interest rates of various terms to maturity all influence some economic decision, such as the amount of money or some other financial asset to hold, or the amount of fixed investment spending to engage in. In this case, including these various interest rates will in general create a substantial multicollinearity problem because interest rates tend to move together. If in fact each of the interest rates has its own separate effect on the dependent variable, it can be extremely difficult to separate out their effects.

Extension

The concept of lateral collinearity expands on the traditional view of multicollinearity, comprising also collinearity between explanatory and criteria (i.e., explained) variables, in the sense that they may be measuring almost the same thing as each other.[10]

See also

References

- ↑ O’Brien, R. M. (2007). "A Caution Regarding Rules of Thumb for Variance Inflation Factors". Quality & Quantity 41 (5): 673. doi:10.1007/s11135-006-9018-6.

- ↑ Farrar, Donald E.; Glauber, Robert R. (1967). "Multicollinearity in Regression Analysis: The Problem Revisited". Review of Economics and Statistics 49 (1): 92–107. JSTOR 1937887.

- ↑ Wichers, C. Robert (1975). "The Detection of Multicollinearity: A Comment". Review of Economics and Statistics 57 (3): 366–368. JSTOR 1923926.

- ↑ Kumar, T. Krishna (1975). "Multicollinearity in Regression Analysis". Review of Economics and Statistics 57 (3): 365–366. JSTOR 1923925.

- ↑ O'Hagan, John; McCabe, Brendan (1975). "Tests for the Severity of Multicolinearity in Regression Analysis: A Comment". Review of Economics and Statistics 57 (3): 368–370. JSTOR 1923927.

- ↑ Chatterjee, S.; Hadi, A. S.; Price, B. (2000). Regression Analysis by Example (Third ed.). John Wiley and Sons. ISBN 0-471-31946-5.

- ↑ Gujarati, Damodar. "Multicollinearity: what happens if the regressors are correlated?". Basic Econometrics (4th ed.). McGraw−Hill. pp. 363–363.

- ↑ Lipovestky; Conklin (2001). "Analysis of Regression in Game Theory Approach". Applied Stochastic Models and Data Analysis 17 (4): 319–330. doi:10.1002/asmb.446.

- ↑ For a detailed discussion, see Van Den Poel, D.; Larivière, B. (2004). "Customer attrition analysis for financial services using proportional hazard models". European Journal of Operational Research 157: 196. doi:10.1016/S0377-2217(03)00069-9.

- ↑ Kock, N., & Lynn, G.S. (2012). Lateral collinearity and misleading results in variance-based SEM: An illustration and recommendations. Journal of the Association for Information Systems, 13(7), 546-580.

Further reading

- Asteriou, Dimitros; Hall, Stephen G. (2011). Applied Econometrics (Second ed.). Palgrave MacMillan. pp. 95–108. ISBN 978-0-230-27182-1.

- Hill, R. Carter; Adkins, Lee C. (2001). "Collinearity". In Baltagi, Badi H. A Companion to Theoretical Econometrics. Blackwell. pp. 256–278. doi:10.1002/9780470996249.ch13. ISBN 0-631-21254-X.

- Johnston, John (1972). Econometric Methods (Second ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. pp. 159–168.

- Kmenta, Jan (1986). Elements of Econometrics (Second ed.). New York: Macmillan. pp. 430–442. ISBN 0-02-365070-2.

- Maddala, G. S.; Lahiri, Kajal (2009). Introduction to Econometrics (Fourth ed.). Chichester: Wiley. pp. 279–312. ISBN 978-0-470-01512-4.

- Pedace, Roberto (2013). Econometrics for Dummies. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. pp. 175–190. ISBN 978-1-118-53384-0.