Mulatto

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| Official population numbers are unknown. | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Latin America, Caribbean, United States, South Africa, Angola, Cape Verde, Mozambique, Guinea-Bissau, Mascarene Islands, United Kingdom, France, Portugal | |

| Languages | |

| Portuguese, Spanish, English, French, Dutch, Afrikaans, Creole languages, others. | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Europeans (mostly Irish, British, Dutch, French and Iberians), Native Americans and African people. |

Mulatto is a term used to refer to a person who is born from one black parent and one white parent, or more broadly, a person of mixed white and black ancestry in any proportion.[1] Contemporary usage of the term is generally confined to situations in which the term is considered relevant in a historical context, as now in the United States people of mixed white and black ancestry rarely choose to self-identify as mulatto.[2]

The term is generally considered archaic in the United States by some and inadvertently derogatory, especially in the African-American community. Accepted modern terms in the United States include "multiracial" and "biracial." The term is widely used in Latin America, the Caribbean and some countries in Africa usually without suggesting any insult. In Latin America, many mulattoes tend to be the result of generational "race-mixing" between white Europeans and black Africans since the slavery period. This is especially true in countries like the Dominican Republic, Brazil, Cuba, Belize, Puerto Rico, and Cape Verde, which are also among the countries with the highest proportions of mulattoes. In most other countries around the world, the United States in particular, mixed European and African ancestry in mulattoes tends in the majority of cases to be of more recent origin.

Etymology

The etymology of the term may derive from the Spanish and Portuguese word mulato, which is itself derived from mula (from old Galician-Portuguese, from Latin mūlus), meaning mule, the hybrid offspring of a horse and a donkey.[3][4][5] Some dictionaries and scholarly works trace the word's origins to the Arabic term muwallad, which means "a person of mixed ancestry".[6]

Muwallad literally means "born, begotten, produced, generated; brought up", with the implication of being born and raised among Arabs, but not of Arab blood. Muwallad is derived from the root word WaLaD (Arabic: ولد direct Arabic transliteration: waw, lam, dal), and colloquial Arabic pronunciation can vary greatly. Walad means, "descendant, offspring, scion; child; son; boy; young animal, young one".

In al-Andalus, Muwallad referred to the offspring of non-Arab/Muslim people who adopted the Islamic religion and manners. It specifically used to refer to the descendants of indigenous Christian Iberians who after several generations of living amongst a Muslim majority adopted their culture and religion. Notable examples of this category include the famous Muslim scholar Ibn Hazm. According to Lisan al-Arab, one of the earliest Arab dictionaries (c. 13th century AD), the term was originally applied to the children of Non-Muslim (often Christian) slaves or Non-Muslim children who were captured in a war and were raised by Muslims to follow their religion and culture. Thus, in this context, the term "Muwalad" has a meaning close to "the adopted". According to the same source, the term does not denote being of mixed race but rather being of foreign-blood and local culture.

According to Julio Izquierdo Labrado,[7] the 19th-century linguist Leopoldo Eguilaz y Yanguas, as well as some Arabian sources[8] muwallad is the etymological origin of mulato. These sources specify that mulato would have been derived directly from muwallad independently of the related word muladí, a term that was applied to Iberian Christians who had converted to Islam during the Moorish governance of Iberia in the Middle Ages.

However, the Real Academia Española (Spanish Royal Academy) casts doubt on the muwallad theory. It states, "The term mulata is documented in our diachronic data bank in 1472 and is used in reference to livestock mules in Documentacion medieval de la Corte de Justicia de Ganaderos de Zaragoza, whereas muladí (from mullawadí) does not appear until the 18th century, according to [Joan] Corominas".[nb 1]

Other scholars such as Werner Sollors cast doubt on the mule etymology for mulatto. In the 18th and 19th centuries, racialists such as Edward Long and Josiah Nott began to assert that mulattoes were sterile like mules. And they projected this belief back onto the etymology of the word mulatto. Sollers points out that this etymology is anachronistic: "The Mulatto sterility hypothesis that has much to do with the rejection of the term by some writers is only half as old as the word 'Mulatto.'"[10]

Africa

In Portuguese-speaking Africa, the term mestiço is used officially to describe people of mixed European and African ancestry.

Of São Tomé and Príncipe's 193,413 inhabitants, the largest segment is defined as mestiço[11] and 71% of the population of Cape Verde is also classified as such.[12] The great majority of their current populations descend from the mixing of the Portuguese that initially settled the islands from the 15th century onwards and the black Africans brought from the African mainland to work as slaves.

In Angola and Mozambique, the mestiço constitute smaller but still important minorities; 2% in Angola[13] and 0.2% in Mozambique.[14]

In Namibia, a current-day population of between 20,000 and 30,000 people, known as Rehoboth Basters, descend from liaisons between the Cape Colony Dutch and indigenous African women. The name Baster is derived from the Dutch word for "bastard" (or "crossbreed"). While some people consider this term demeaning, the Basters proudly use the term as an indication of their history.

In South Africa, the term Coloured (also known as Bruinmense, Kleurlinge or Bruin Afrikaners in Afrikaans) used to refer to individuals who possess some degree of sub-Saharan ancestry, but not enough to be considered black under the law of South Africa. In addition to European ancestry, they may also possess ancestry from India, Indonesia, Madagascar, Malaysia, Mauritius, Sri Lanka, China and/or Saint Helena. There was extensive combining of these diverse heritages in the Western Cape, but in other parts of southern Africa, the coloured usually were descendants of two distinct ethnic groups - primarily Africans of various tribes and European colonists.

Thus, in KwaZulu-Natal, most Coloureds were descended from British and Zulu heritage, while Zimbabwean coloureds were descended from Shona or Ndebele mixing with British and Afrikaner settlers. Griqua, on the other hand, are descendants of Khoisan and Afrikaner trekboers. Despite these major differences, in the South African context, they were historically considered "coloured," as descended from more than one "naturalised" racial group. Such persons may not use the term, and individually identify as "black" or "Khoisan" or just "South African". The Coloureds comprise 8.8% (about 4.4 million people) of South Africa's population.

In Mauritius, Réunion and the Seychelles, there are numerous mixed-race people. In Mauritius, they are called creoles, and in Réunion they are called 'cafres.

Afro-European clans

- Akus

- Americo-Liberians

- Fernandinos

- Sherbro Hubris

- Sherbro Tuckers

- Sherbro Caulkers

- Sherbro Rogers

- Sherbro Clevelands

- Creoles

- The ruling branch of the Tswana Khamas

- Yoruba Saro Ransome-Kuti family

Latin America and the Caribbean

Mulattoes represent a significant part of the population of various Latin American and Caribbean countries:[15] Dominican Republic (73%) (all mixed race people),[15][nb 2] Brazil (49.1% mixed and Black, Mulattoes(20.5%), Mestizos/mamelucos(21.3%), Eurasian(0.2%) and Blacks(7.1%)),[16][17] Belize (25%), Cuba (24.86%),[15] Colombia (25%),[15] Haiti (15-20%).[15]

The roughly 200,000 Africans brought to Mexico were for the most part absorbed by the mestizo populations of mixed European and Amerindian descent. Many of the Africans brought to Mexico arrived in the port of Veracruz and were taken to other parts of Latin America. The state of Guerrero once had a large population of African slaves. Other Mexican states inhabited by people with some African ancestry, along with other ancestries, include Oaxaca, Veracruz, and Yucatán.

According to the summary of Encyclopedia Britannica, more than 50% of Cubans are mulatto and about 40 percent of Brazilian people are mulatto/mestizo.[18]

In colonial Latin America, mulato could also mean an individual of mixed African and Native American ancestry.[19] However, today those who have indigenous and black African ancestry in Latin America are more frequently called Zambos in Spanish or Cafuzo in Portuguese. In the United States, persons who are mixtures of African American and Native American have been historically called blacks, or black Indians; in other cases they have been classified solely or identify as African American.[20] Federally recognized Indian tribes have insisted that membership is related more to culture than race, and many have had mixed-race members who are fully members of the tribes as their primary identification.

Puerto Rico

In a 2002 genetic study of maternal and paternal direct lines of ancestry of 800 Puerto Ricans, 61% had mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) from an Amerindian female ancestor, 27% inherited MtDNA from a female African ancestor and 12% had MtDNA from a female European ancestor.[21] Conversely, patrilineal direct lines, as indicated by the Y chromosome, showed that 70% of Puerto Rican males in the sample have Y chromosome DNA from a male European ancestor, 20% inherited Y-DNA from a male African ancestor, and less than 10% inherited Y-DNA from a male Amerindian ancestor.[22] As these tests measure only the DNA along the direct matrilineal and patrilineal lines of inheritance, they cannot tell with certainty what percentage of European or African ancestry any individual has.

During this whole period, Puerto Rico had laws like the Regla del Sacar or Gracias al Sacar, by which a person with African ancestry could be considered legally white if he could prove that at least one person per generation in the last four generations had also been legally white. People of black ancestry with known white lineage were classified as white, the opposite of the "one-drop rule" in the United States.[23]

Brazil

Studies carried out by the geneticist Sergio Pena conclude the average white Brazilian is 80% European, 10% Amerindian, and 10% African/black.[24] Another study, carried out by the Brazilian Journal of Medical and Biological Research, concludes the average white Brazilian is (>70%) European.[25]

According to the IBGE 2000 census, 38.5% of Brazilians identified as pardo, i.e. of mixed ancestry.[26][27] This figure includes mulatto and other multiracial people, such as people who have European and Amerindian ancestry (called caboclos), as well as assimilated, westernized Amerindians and mestizos with some Asian ancestry. A majority of mixed-race Brazilians have all three ancestries: Amerindian, European, and African. According to the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics census 2006, some 42.6% of Brazilian identify as pardo.[28]

Some of White Brazilians (48.4%) have some mixed-race ancestry (both Subsaharan African and Amerindian ancestry). The average ancestry of Afro-Brazilians who self-identified as de raça negra or de cor preta, i.e. Brazilians of Black African origin (6.9%) and not self-perceived multiracials (42.6%), is 50% European, 10% Amerindian and 40% African.

The term mulatto (mulato in Portuguese) does not carry a racial connotation and is used along with other terms, such as moreno, light-moreno and dark-moreno. These refer more to skin color and features than purely ethnicity, although they can also refer to hair color alone - e.g. "light-moreno" would be "caucasian brunette". Such terms are also used for other multiracial people in Brazil, and they are the popular terms for the pardo skin color used on the 2000 official census.

An autosomal DNA study, which measures total genetic contribution, of students at a school in the poor periphery of Rio de Janeiro, found that the "pardos" (including mulattoes) were genetically more than 80% European. "The results of the tests of genomic ancestry are quite different from the self made estimates of European ancestry", say the researchers. The test results showed that the proportion of European genetic ancestry was higher than students expected. The "pardos", for example, identified as 1/3 European, 1/3 African and 1/3 Amerindian before the tests.[29][30] Students classified as white had overestimated their ratio of African and Amerindian genetic ancestry.[29]

Haiti

Mulattoes make up at least 15% of the nation's population. In Haiti history they are known as the influential groups of people who held positions in office and they having privileged over slaves though their mothers were slaves. The mulattoes have retained their elite position, based on education and social capital, which is highly evident in the political, economic and cultural hierarchy in present-day Haiti. Numerous leaders throughout Haiti's history have been mulattoes.[31] Alexandre Pétion, born to a Haitian mother and a wealthy French father, was the first President of the Republic of Haiti. His father had arranged for his education.

The struggle within Haiti between the mulattoes led by André Rigaud and the black Haitians led by Toussaint Louverture devolved into the War of the Knives.[32][33] In the early period of independence, former slaves of majority black ancestry led the government, as it was slaves who had done most of the fighting to achieve independence.

United States of America

Antebellum era

During the colonial and post-revolutionary slaveholding periods, many black women had sexual relations, often against their will, with white men. According to historian F. James Davis,

Rapes occurred, and many slave women were forced to submit regularly to white males or suffer harsh consequences. However, slave girls often courted a sexual relationship with the master, or another male in the family, as a way of gaining distinction among the slaves, avoiding field work, and obtaining special jobs and other favored treatment for their mixed children (Reuter, 1970:129). Sexual contacts between the races also included prostitution, adventure, concubinage, and sometimes love. In rare instances, where free Blacks were concerned, there was even marriage (Bennett, 1962:243-68).[34]

Many of these unions produced children. Mixed-race children also resulted from relationships between African men and European women, including indentured servants in the colonial years before the hardening of slavery as a racial caste.[35][36] Some of their descendants assimilated, marrying white spouses over several generations, and passing into the European population because of their appearance.

Some wealthy planters, especially widowers or young men before they married, took women slaves as concubines, as did John Wayles, after being widowed three times. His daughter Martha Wayles, born to his first wife, married Thomas Jefferson. Wayles' youngest daughter by his slave concubine, Elizabeth Hemings, was Sally Hemings. The half-sister of Jefferson's late wife, she became Jefferson's concubine and had six children with him, four surviving to adulthood. They were seven-eighths white. Three passed into white society as adults. John Wayles Jefferson, a grandson of Sally Hemings and Thomas Jefferson, was accepted as white and served as a colonel in the Union Army in the Civil War, later becoming a successful cotton broker in Memphis, Tennessee.

Some mixed-race persons in the South became slave owners, and many supported the Confederacy during the Civil War. For example, William Ellison owned 60 slaves. Andrew Durnford of New Orleans, which had a large population of free people of color, mostly of French descent and culture, was listed as owning 77 slaves. In Louisiana free people of mixed race constituted a third class between white colonists and the mass of slaves.[37] Other mulattoes became abolitionists and supported the Union. For example, Mary Ellen Pleasant and Thomy Lafon used their fortunes to support the abolitionist cause. Francis E. Dumas of New Orleans, who was a free person of color, emancipated all his slaves and organized them into a company in the Second Regiment of the Louisiana Native Guards.[38]

Historically in the American South, the term mulatto was also applied at times to persons with a parents of Native Americans and African Americans in general.[20] For example, a 1705 Virginia statute reads as follows:

"And for clearing all manner of doubts which hereafter may happen to arise upon the construction of this act, or any other act, who shall be accounted a mulatto, Be it enacted and declared, and it is hereby enacted and declared, That the child of an Indian and the child, grand child, or great grand child, of a negro shall be deemed, accounted, held and taken to be a mulatto."[39]

In early American history, the term mulatto was also used to refer to persons of Native American and European ancestry. Certain tribes of Indians of the Inocoplo family in Texas referred to themselves as "mulatto" [40] At one time, Florida's laws declared that a person from any number of mixed ancestries would be legally defined as a mulatto, including White/Hispanic, Black/Indian, and just about any other mix as well. [41]

Contemporary era

Mulatto was used as an official census racial category in the United States until 1930. (By that time, several southern states had adopted one-drop rule as law, and southern Congressmen pressed the US Census Bureau to drop the mulatto category: all persons had to be classified as "black" or "white".) At that time, the term was primarily applied as a category to persons of mixed African and European descent. During the colonial and early federal period, in the Southern colonies and states, it was sometimes applied persons of any mixed ethnicity, including Native American and European. During the early census years of the United States beginning in 1790, "mulatto" was applied to persons who were identifiably of mixed African-American and Native American ancestry.[42][43][44][45] Mulatto was also used interchangeably with terms like "Turk", leading to ambiguity when referring to North Africans and Middle Easterners, who were, however, of limited number in the colonies.[46] In the 2000 United States Census, 6,171 Americans self-identified as having mulatto ancestry.[47] Since then, multi-racial people have been allowed to identify as having more than one type of ethnic ancestry.

In addition, the term "mulatto" was also used to refer to the children of whites who intermarried with South Asian indentured servants brought over to the British American colonies by the East India Company. For example, a daughter born to an South Asian father and Irish mother in Maryland in 1680 was classified as a "mulatto" and sold into slavery.[48] The more usual case was the use of the principle of partus sequitur ventrem, adopted by Virginia in 1662, which made the status of a child dependent on the status of the mother. Children born of slave mothers were born into slavery, regardless of who their fathers were; children born to white mothers were free, even if mixed race.

Although still in use by some, the term mulatto has fallen out of favor, and is considered offensive by some in the United States.[49] Today, more popular terms include biracial, multiracial, mixed-race, and multi-ethnic.

-

Abdullah Abdurahman (a coloured activist from South Africa)

-

_-_Google_Art_Project_2.jpg)

Alexandre Dumas in 1855

-

Bob Marley was born to a white Jamaican father and black Jamaican mother

-

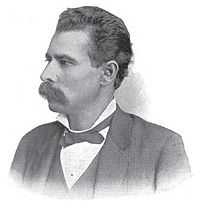

P.B.S. Pinchback

Colonial references

See also

- Afro Argentine: Colonial racial categories

- Afro-American peoples of the Americas

- Afro-Hispanic people

- Afro-Latin American

- Cafres

- Cholo

- Melungeon

- Tragic mulatto

- Rhineland Bastard

General:

References

- Notes

- ↑ Corominas describes his doubts on the theory as follows: "[Mulato] does not derive from the Arab muwállad, 'acculturated foreigner' and sometimes 'mulatto' (see 'Mdí '), as Eguílaz would have it, since this word was pronounced 'moo-EL-led' in the Arabic of Spain; and Reinhart Dozy (Supplément aux Dictionaires Arabes, Vol. II, Leyden, 1881, 841a) rejected in advance this Arabic etymology, indicating the true one, supported by the Arabic nagîl, 'mulatto', derived from nagl, 'mule'."[9]

- ↑ In the Dominican Republic, the mulatto population has also absorbed the Taíno Amerindians once present in that country, based on a 1960 census that included colour categories such as white, black, yellow, and mulatto. Since then, racial components have been dropped from the Dominican census.

- Citations

- ↑ "Mulatto". Merriam-Webster.com. Merriam-Webster, Inc. Retrieved 2015-01-31.

- ↑ White Americans Admixture Serving History; "The Ancestry of Brazilian mtDNA Lineages" National Library of Medicine, NIH; "Y-STR diversity and ethnic admixture in White and Mulatto Brazilian population samples" Scielo.

- ↑ "Chambers Dictionary of Etymology". Robert K. Barnhart. Chambers Harrap Publishers Ltd. 2003. p. 684.

- ↑ Harper, Douglas. "mulatto". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 2008-07-14.

- ↑ "Diccionario de la Lengua Española - Vigésima segunda edición" (in Spanish). Real Academia Española. Retrieved 2008-07-14.

- ↑ Jack D. Forbes (1993). Africans and Native Americans: the language of race and the evolution of Red-Black peoples. University of Illinois Press. p. 145. ISBN 978-0-252-06321-3.

- ↑ Izquierdo Labrado, Julio. "La esclavitud en Huelva y Palos (1570-1587)" (in Spanish). Retrieved 2008-07-14.

- ↑ Salloum, Habeeb. "The impact of the Arabic language and culture on English and other European languages". The Honorary Consulate of Syria. Retrieved 2008-07-14.

- ↑ Corominas, Joan and Pascual, José A. (1981). Diccionario crítico etimológico castellano e hispánico, Vol. ME-RE (4). Madrid: Editorial Gredos. ISBN 84-249-1362-0.

- ↑ Werner Sollors, Neither Black Nor White Yet Both, Oxford University Press, 1997, p. 129.

- ↑ "São Tomé and Príncipe". Infoplease. Pearson Education, Inc. Retrieved 2008-07-14.

- ↑ "Cape Verde". Infoplease. Pearson Education, Inc. Retrieved 2008-07-14.

- ↑ "Angola". Infoplease. Pearson Education, Inc. Retrieved 2008-07-14.

- ↑ "Mozambique". Infoplease. Pearson Education, Inc. Retrieved 2008-07-14.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 15.4 "CIA - The World Factbook -- Field Listing - Ethnic groups". CIA. Retrieved 2008-06-15.

- ↑ "Pardo category includes Castizos, Mestizos, Caboclos, Gypsies, Eurasians, Hafus and Mulattoes". www.nacaomestica.org/. 2015. Retrieved 2015-04-15.

- ↑ Black population becomes the majority in Brazil — MercoPress

- ↑ "mulatto". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2009-11-22.

- ↑ Schwaller, Robert C. (2010). "Mulata, Hija de Negro y India: Afro-Indigenous Mulatos in Early Colonial Mexico". Journal of Social History 44 (3): 889–914. doi:10.1353/jsh.2011.0007.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Miles, Tiya (2008). Ties that Bind: The Story of an Afro-Cherokee Family in Slavery and Freedom. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-25002-4. Retrieved 2009-10-27.

- ↑ Martínez Cruzado, Juan C. (2002). "The Use of Mitochondrial DNA to Discover Pre-Columbian Migrations to the Caribbean:Results for Puerto Rico and Expectations for the Dominican Republic" (PDF). KACIKE: The Journal of Caribbean Amerindian History and Anthropology (Special): 1–11. ISSN 1562-5028. Retrieved 2008-07-14. Archive copy at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Gonzalez, Juan (2003-11-04). "Puerto Rican Gene Pool Runs Deep". Puerto Rico Herald. Retrieved 2008-07-14.

- ↑ Kinsbruner, Jay (1996). Not of Pure Blood. Duke University Press.

- ↑ "Black in Brazil: a question of identity", BBC News

- ↑ "DNA tests probe the genomic ancestry of Brazilians", Brazilian Journal of Medical and Biological Research

- ↑ "Last stage of publication of the 2000 Census presents the definitive results, with information about the 5,507 Brazilian municipalities". Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística. Retrieved 2008-07-14.

- ↑ "Populaçăo residente, por cor ou raça, segundo a situaçăo do domicÌlio e os grupos de idade - Brasil" (PDF). Censo Demográfico 2000. Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística. Retrieved 2008-07-14.

- ↑ "Sintese de Indicadores Sociais" (PDF). Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística. Retrieved 2008-07-14.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 "Rio de Janeiro's Black and Multiracial people carry more European ancestry in their genes than they supposed, according to research", MEIO News

- ↑ "Color, Race, and Genomic Ancestry in Brazil: Dialogues Between Anthropology and Genetics" (PDF). Current Anthropology 50 (6). 2009. Retrieved 2013-01-07.

- ↑ Smucker, Glenn R. "The Upper Class". A Country Study: Haiti (Richard A. Haggerty, editor). Library of Congress Federal Research Division (December 1989).

- ↑ Corbett, Bob. "The Haitian Revolution of 1791-1803". Webster University.

- ↑ Smucker, Glenn R. "Toussaint Louverture". A Country Study: Haiti (Richard A. Haggerty, editor). Library of Congress Federal Research Division (December 1989).

- ↑ Floyd James Davis, Who Is Black?: One Nation's Definition, pp. 38-39

- ↑ Dorothy Schneider, Carl J. Schneider, Slavery in America, Infobase Publishing, 2007, pp. 86-87.

- ↑ Felicia R Lee, Family Tree’s Startling Roots, New York Times. Accessed November 3, 2013.

- ↑ Joseph Conlin (2011). The American Past: A Survey of American History. Cengage Learning, p. 370. ISBN 111134339X

- ↑ Shirley Elizabeth Thompson, Exiles at Home: The Struggle to Become American in Creole New Orleans, Harvard University Press, 2009, p. 162.

- ↑ General Assembly of Virginia (1823). "4th Anne Ch. IV (October 1705)". In Hening, William Waller. Statutes at Large. Philadelphia. p. 252. Retrieved 30 September 2014.

- ↑ "Mulato Indians | The Handbook of Texas Online| Texas State Historical Association (TSHA)". Tshaonline.org. Retrieved 2013-01-07..

- ↑ Sewell, Christopher Scott; Hill, S. Pony (2011-06-01). The Indians of North Florida: From Carolina to Florida, the Story of the Survival of a Distinct American Indian Community. Backintyme. Retrieved 2013-01-07.

- ↑ "Mulatto - An Invisible American Identity". Race Rekations. About.com. Retrieved 2008-07-14.

- ↑ "Introduction". Mitsawokett: A 17th Century Native American Community in Central Delaware.

- ↑ "Walter Plecker's Racist Crusade Against Virginia's Native Americans". Mitsawokett: A 17th Century Native American Settlement in Delaware. Retrieved 2008-07-14.

- ↑ Heite, Louise. "Introduction and statement of historical problem". Delaware's Invisible Indians. Retrieved 2008-07-14.

- ↑ de Valdes y Cocom, Mario. "The Van Salee Family". The Blurred Racial Lines of Famous Families. PBS Frontline. Retrieved 2008-07-14.

- ↑ Mulatto ancestry in 2000 U.S census

- ↑ Assisi, Francis C. (2005). "Indian-American Scholar Susan Koshy Probes Interracial Sex". INDOlink. Retrieved 2009-01-02.

- ↑ Zirin, Dave and Wolf, Sherry (2009-09-15). "Stop the Savage Sports Sex Scares". The Nation. Retrieved 2012-02-23.

Further reading

- McNeil, Daniel (2010). Sex and Race in the Black Atlantic: Mulatto Devils and Multiracial Messiahs. Routledge.

- Sweet, Frank W. (2005). Legal History of the Color Line: The Rise and Triumph of the One-Drop Rule. Backintime Publishing.

- Tenzer, Lawrence Raymond (1997). The Forgotten Cause of the Civil War: A New Look at the Slavery Issue. Scholars' Pub. House.

- Talty, Stephan (2003). Mulatto America: At the Crossroads of Black and White Culture: A Social History. HarperCollins Publishers Inc.

- Gatewood, Willard B. (1990). Aristocrats of Color: The Black Elite, 1880-1920. Indiana University Press.

- Eguilaz y Yanguas, Leopoldo (1886). Glosario de las palabras españolas (castellanas, catalanas, gallegas, mallorquinas, portuguesas, valencianas y bascongadas), de orígen oriental (árabe, hebreo, malayo, persa y turco) (in Spanish). Granada: La Lealtad.

- Freitag, Ulrike; Clarence-Smith, William G., ed. (1997). Hadhrami Traders, Scholars and Statesmen in the Indian Ocean, 1750s-1960s. Social, Economic and Political Studies of the Middle East and Asia 57. Leiden: Brill. p. 392. ISBN 90-04-10771-1. Retrieved 2008-07-14. Engseng Ho, an anthropologist, discusses the role of the muwallad in the region. The term muwallad, used primarily in reference to those of "mixed blood", is analyzed through ethnographic and textual information.

- Freitag, Ulrike (December 1999). "Hadhrami migration in the 19th and 20th centuries". The British-Yemeni Society. Retrieved 2008-07-14.

- Myntti, Cynthia (1994). "Interview: Hamid al-Gadri". Yemen Update (American Institute for Yemeni Studies) 34 (44): 14–9. Retrieved 2008-07-14.

- Williamson, Joel (1980). New People: Miscegenation and Mulattoes in the United States. The Free Press.

External links

| Look up mulatto in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- A Brief History of Census “Race”

- Surprises in the Family Tree

- The Mulatto Factor in Black Family Genealogy

- Dr. David Pilgrim, "The Tragic Mulatto Myth", Jim Crow Museum, Ferris State University

- At "Race Relations", in-depth research links on Mulattoes, About.com

- Encarta's breakdown of Mulatto people (Archived 2009-11-01)

-

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Mulatto". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Mulatto". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

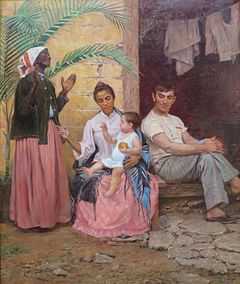

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Casta terms for miscegenation in Spanish America | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

.jpg)